Montreal’s McCord Museum Opens Up to Indigenous Perspectives

Founded by David Ross McCord, an avid collector with a passion for history, the McCord Museum opened in Montreal just over 100 years ago. While the initial core of the museum’s collections reflected the founder’s interest in First Peoples and major events in Canadian history, many objects also came from the collections of the Natural History Society of Montreal (created in 1827), as well as the museums of McGill University, including the Redpath, which had divested themselves of their ethnographic collections over time. Lastly, several private donations also enhanced the holdings of the McCord Museum, which is today the guardian of a rich and unique collection.

The Indigenous Cultures Collection

Composed of over 16,000 archaeological artefacts and historic objects covering close to 12,000 years of history, the Indigenous Cultures collection is one of the most significant collections of its kind in Canada, noted for the remarkable diversity and quality of its contents.

Eloquent examples of the material culture of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people living primarily in Canada but also in certain regions of the United States, Siberia, and Greenland, these objects reflect the magnificence of Indigenous cultures, the great diversity of their artistic expression, and their extraordinary ability to adopt and incorporate foreign influences.

These objects evoke centuries-old traditions, world views, and knowledge that remain relevant today. It goes without saying that the management, documentation, and development of such a collection must be carried out with current considerations in mind, making way for Indigenous voices and perspectives.

Object Management and Access

For several years, the McCord Museum has been committed to an approach that aims to increase this collection’s relevance and accessibility, ensuring that its reach reflects contemporary Indigenous concerns and perspectives. Remaining sensitive and attentive to Indigenous ideas and protocols is key to maintaining good relations with the communities whose objects are preserved at the museum. For example, not only are certain conserved objects never displayed, but they are also hidden from view in the storage spaces — at the request of the communities concerned. This is the case, for instance, with Iroquois masks that are spiritual in nature. To respect the protocols and concerns of the communities of origin, every year, the museum welcomes representatives who come to conduct ceremonies relating to these objects.

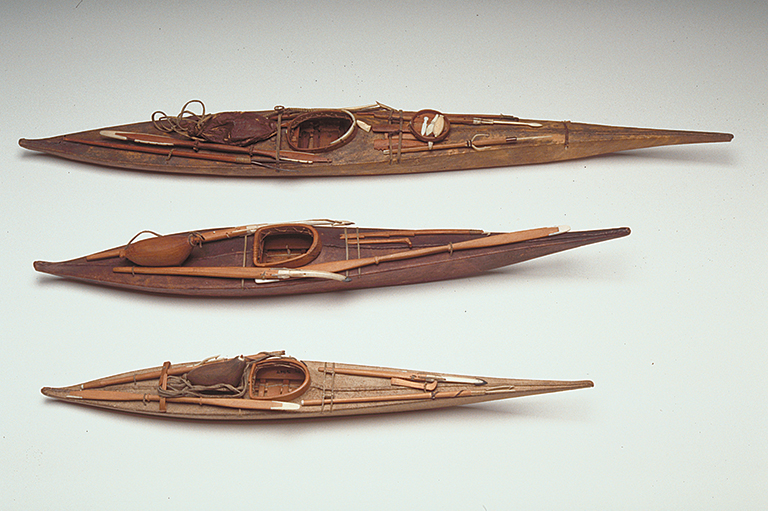

With a goal of remaining relevant to Indigenous individuals and communities, the museum is committed to continuing its best efforts to make this cultural heritage accessible to the nations and communities concerned. For example, an Inuk artist seeking to view miniature reproductions of kayaks for a personal project can ask to work directly in the presence of these objects for a few hours, thereby benefiting from special access to these items from his own culture. To take another example, should a Haida researcher require specific images of a cultural object to make a reproduction in his community on the far western side of the country, the curator will make it a point of principle to go into the stores and take photographs according to the researcher’s instructions, getting the exact angles that will allow him to understand how the object is built and assembled.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Object Documentation

One of the museum curator’s tasks involves documenting the objects that make up the collection. As an exercise that can be both fascinating and painstaking, the reconstruction of the objects’ history must be carried out with great care. As museums are custodians of objects amassed over the years, knowledge about these objects is often derived from past collection practices and even the interests and viewpoints of collectors from another era. And since Indigenous cultures were for a long time overlooked and stereotyped, past ideas about certain elements of their material culture can be passed down through time to the present day. This is how wampum belts — important objects of a diplomatic and ceremonial nature — ended up in some of the country’s numismatic collections! This means that the information accompanying an object — when present, which is not always the case — is not necessarily a guarantee of truth. This scarcity of valid or verified information requires the curator and material culture researcher to demonstrate ingenuity, seek sources that are as varied as possible, put things into perspective, and show no hesitation in questioning the information at hand.

The McCord Museum also recognizes that knowledge relating to the objects it preserves is often found beyond its walls. When Indigenous researchers, artists, or elders tell the museum that a certain object means a certain thing or was used in a specific context, the members of the museum team make sure to include this local or community knowledge in their databases, providing a better understanding of the object’s history or symbolism. This is how the descriptions of most Haida objects in the McCord’s collection were able to benefit from the expert eye of eminent artist Robert Davidson during the development of the exhibition Haida Art: Mapping an Ancient Language (2006), and how curator Betty Kobayashi Issenman, with the help of members of various Inuit communities, was able to catalogue most of the Inuit clothing in the exhibition IVALU: Traditions of Inuit Clothing (1988-1989).

Development and Exhibition

Showcasing Indigenous objects in exhibitions open to the public also requires certain precautions and sensitivities. At the McCord Museum, the exhibitions are developed with the help of Indigenous curators or with the contribution of external advisory committees, and the content is generally established in collaboration with Indigenous individuals and communities whose history and culture are being presented. This is a way to give Indigenous people a voice, to highlight their views and testimonies, and to give them a place to tell their story within the walls of the museum. This approach also adds value to certain perspectives relating to the interpretation of history. Putting an emphasis on certain historical facts that contributed to the marginalization of Indigenous peoples and cultural communities is a way of decolonizing the telling of our shared history.

When an exhibition is under development, the museum must sometimes bear in mind that certain objects must not be displayed to the public. This is especially true with sacred or ceremonial objects that were made to be used and shown in specific cultural or spiritual contexts. The museum will only display such an object when it has received the authorization to do so from the community of origin — otherwise, it refrains from exhibiting it.

By way of example, the museum commissioned a new teueikan (a ceremonial Innu drum that hunters use to communicate with the spirit of the animal they are hunting) from contemporary artisans for use in its new exhibition on Indigenous cultures (Indigenous Voices of Today: Knowledge, Trauma, Resilience), rather than displaying a magnificent old teueikan it has preserved but whose precise origin is unknown. From a museological point of view, it is sometimes frustrating to be unable to exhibit these uniquely beautiful objects, but in terms of respecting and maintaining good relationships with Indigenous communities, the museum is convinced this is the right thing to do.

As an exhibition is being developed, there are many behind-the-scenes challenges that generally remain invisible to eventual visitors. Given that there are currently over 640 Indigenous communities across Canada, divided into three distinct groups — First Nations, Inuit, and Métis — , how can we make sure that everyone feels represented in an extremely restricted exhibition space merely covering a few square metres? What themes should be selected to tell the story of rich and diverse cultures that have continued to evolve for hundreds of years since the first European contact? How do we properly address sensitive and difficult histories like those of the residential schools and of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls? Close collaboration with the main parties concerned helps resolve these difficulties.

Another issue that can frustrate historians and curators accustomed to writing scientific articles with multiple footnotes: the limited number of words allocated to explanatory panels or cards used to describe objects on display. While a whole book could be written on such a complex reality, the museum must sometimes settle on a 60-word paragraph to accommodate visitors and avoid inevitable museum fatigue. A truly interesting and stimulating editorial challenge!

Indigenization and Decolonization at the McCord Museum

The McCord Museum is engaged in a process of indigenization and decolonization aimed at creating a climate of respect and openness between the museum and Indigenous nations. For over 30 years now, the museum’s professional procedures have incorporated Indigenous knowledge and practices in exhibitions, educational programs, research, and documentation. Since the reopening of the museum in 1992, exhibitions dealing with Indigenous subject matter have been developed in collaboration and in consultation with stakeholders from the Indigenous milieu and, when possible, a place has been made for contemporary Indigenous artists in the exhibitions. Travelling Indigenous exhibitions have also been presented. For a few years now, an artist-in-residence program has given several Indigenous artists the opportunity to access the museum’s collections, allowing them to create their own work, which is then displayed for a few months.

In addition to having two Indigenous members on its board of trustees and having hired an Indigenous curator, the McCord Museum recently established a permanent Indigenous advisory committee, whose primary focus is to take an informed, cross-disciplinary look at the museum’s indigenization initiatives.

The museum is confident in adopting this well-thought-out approach: making room for Indigenous voices within the institution’s very structure and involving Indigenous peoples in each project that concerns them, thereby given them the opportunity to tell their stories, ensuring that their points of view are considered and that their voices are heard.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Also in 50 merveilles de nos musées

This special issue of Histoire Canada highlights beautiful treasures from Franco-Canadian communities across Canada. Available in French only.