Saving Endangered Heritage

The first Catholic mass on Canadian soil was celebrated on September 7, 1535, at L’Isle-aux-Coudres, in the St. Lawrence River, by the two chaplains accompanying French explorer Jacques Cartier and his crew. In the winter that followed, the exploration party stayed in Stadacona, the site of present-day Quebec City, where twenty-five of Cartier’s men died of scurvy. Cartier erected an altar at the foot of a tree in the forest, where he prayed for divine intervention. He placed an image of the Virgin Mary at the altar and organized all of those who could still walk into a procession that chanted psalms and sang “Ave maris stella,” a popular hymn among Breton sailors.

The first mass and first pilgrimage in the country required the use of liturgical clothing and objects, statues, and song books brought from Europe. These objects were probably taken back to France; but the ones that the first colonists and missionaries brought later, along with those made on Canadian soil, would go on to comprise an important part of the country’s cultural and artistic heritage.

In Quebec and elsewhere in Canada, the churches that became the centre of towns and villages were embellished by painters and sculptors who often produced the bulk of their work for this purpose. People of different communities and nationalities each brought their own characteristic traditions, architecture, and religious objects. Amid this heritage, the contribution of male and female religious congregations is distinguished by the sheer quantity of objects and archives they conserved, and by the diversity of establishments they managed.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The Founding Communities

The first religious community to settle in New France, the Récollets, arrived in 1615 with the French navigator Samuel de Champlain, eighty years after Jacques Cartier’s stay in Stadacona. The Récollets soon built a chapel near Champlain’s base at the Habitation de Québec, and began travelling across the territory to encounter Indigenous peoples.

Five years later, the community built a monastery and a church on the banks of the Saint-Charles River in Quebec. The Hôpital général de Québec stands on the site today, bearing traces of the original establishment.

To ornament their church, celebrate mass, and convert Indigenous people, the Récollets brought religious icons, sculptures, and liturgical objects with them from France. As a monastic community, they needed furniture, cooking items, and tools to work the land and to build their spaces for living and for prayer. Following the arrival of the Jesuits in 1625, the Augustines and Ursulines landed in Quebec City on August 1, 1639. These were the first female religious communities in New France and they were dedicated to healing the sick and providing education. They carried with them the founding documents of their mission, as well as religious objects, medical reference books, and didactic works.

In New France, male and female religious communities — including the Récollets, Jesuits, Sulpicians, Augustines, Ursulines, Hospitaliéres de St. Joseph, and the Congregation of Notre Dame — built the first convents, schools, and hospitals. They played a decisive role in the colony’s development and the occupation of the territory. After these congregations, others were founded or arrived from France to spread across the continent from coast to coast. All these congregations also required objects for prayer, for community life, and for their specific mission. Now preciously preserved, these objects constitute a material heritage of national scope and significance.

A Heritage at Risk

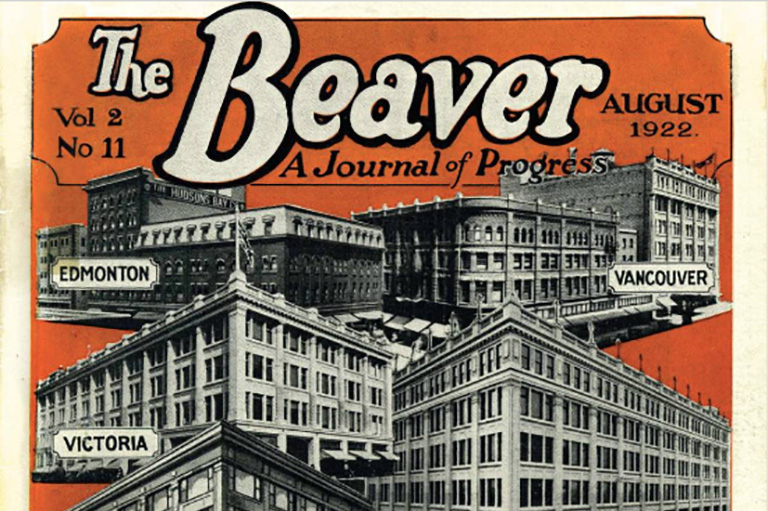

Religious congregations expanded significantly in the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. In Quebec, in particular, they took charge of small and large schools, specialized teaching establishments, hospitals, asylums for the treatment of the mentally ill, services to the clergy, places of pilgrimage, Catholic outreach chaplaincies, places of contemplative prayer, missionary activity around the world, and religious publishing houses.

From the beginning, religious congregations knew the importance of recording the origin and evolution of their social and religious work. Their archives contain founding documents and legal acts, correspondence, annals, and construction plans. Several communities, even small ones, in all regions of the country, opened museums and archives. The preservation of a large part of our collective memory is due to their vigilance and competence.

Beginning in the 1970s, religious congregations faced a rapid and irreversible decline in numbers. In Quebec, most of their establishments were ceded to the provincial government, and their convents and monasteries were closed. It wasn’t long before the management of their archives and collections exceeded the capabilities of an increasingly small number of religious men and women. After their valuable objects were collected at the mother house, decisions had to be made regarding the transfer of these possessions. Where should they go? How? By what means? With occasional assistance from government authorities, the congregations found innovative and inspiring solutions. Some came together to create central archives or collections. Among them, the Augustines de la Miséricorde de Jésus were the instigators of a precedent-setting project.

The Example of the Augustines

In 1639 the Augustines of Dieppe, France, founded the first hospital in what would eventually become Canada — the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec City. This community of caregivers went on to found eleven more establishments on the territory that is now the province of Quebec. Over the centuries, they amassed a linear kilometre of archives and antique books, along with a collection of over fifty thousand objects used in prayer, medicine, and everyday life. Their medical collection testifies to more than three centuries of scientific and technical innovation dedicated to health care and to the alleviation of suffering.

Faced with dwindling numbers, the Augustines found themselves obliged to gradually close their convents, while their hospitals were taken over by the Quebec government. They created a public trust to which they ceded their archives and collections, along with the monastery of the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec. With government assistance, the trust turned the monastery into a museum and archive. A non-profit organization handles the site management.

The museum opened to the public on August 1, 2015—exactly 376 years after the arrival of the first Augustines. The sixty-five rooms where the sisters slept have been made available as accommodations to guests seeking to experience the calm and beautiful setting. Visitors and guests to the monastery are surrounded by heritage artifacts in a space that has been inhabited for more than 375 years.

From convent to museum

Some of the objects in the collection served a sacred purpose. They were used in prayer, devotions, and liturgical rituals. While they may have lost their religious purpose in moving into the museum, they nevertheless remain evocative objects. They tell the story and bear witness to the faith of those who made a place for them in their lives.

Once it has made its way into a museum, an object is no longer in a sacred context, yet it remains an exceptional item. Like any collection piece, it is handled with care and stored in a way that ensures its safety and preservation. When it is exhibited, it is placed in a display case with lighting that highlights its artistic, ethnological, and historical values. It becomes part of a museological record, an object that is part of the memory of the world from which it came, paying tribute to the artist or artisan who made it. The different view provided by the museum setting contributes, in another way, to the “sacralization” of the religious object.

At a crossroads

With the closing of convents and monasteries taking place over a relatively short period of time, many objects and important archives are at risk of disappearing if they are not put in the care of competent institutions. Congregations are currently working on innovative solutions in this regard. Some are seeking partners to ensure their efforts are successful. But the challenge remains for most of them. As the keepers of memories die, the understanding of what this heritage represents for those who knew it is also lost. Given the advanced age of most monks and nuns, the next decade will be critical to the proper preservation of this heritage whose priceless value is often unrecognized.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Also in 50 merveilles de nos musées

This special issue of Histoire Canada highlights beautiful treasures from Franco-Canadian communities across Canada. Available in French only.