Mysterious Madonna

The devotional plaque bearing the image of the Virgin Mary arrived at the Canadian Conservation Institute in 2018 in need of care. This was perhaps not surprising: The plaque had been buried in the foundation of the Notre-Damede- Bon-Secours chapel in Old Montreal for close to three hundred years.

A recycled printing plate from the first half of the seventeenth century, the unassuming rectangle of engraved copper depicts the Virgin Mary holding the baby Jesus in her arms while crushing a dragon that represents the Devil. Encircling the Virgin and child is a banner with a Latin inscription, written in mirror image: “O saevis inimica Virgo belluis da dextram misero et tecum me tolle per undas.” The first part of the inscription, “saevis inimica Virgo belluis,” translates as “virgin, foe of savage beasts” and is a quote from an ode by the ancient Roman poet Horace. The second part of the inscription, “da dextram misero et tecum me tolle per undas,” translates as “give this wretch your hand, and take me with you through the waves.” It is a quote from the epic poem The Aeneid, written by the Roman poet Virgil. Neither of the original quotes refers to the Virgin Mary, since both poets lived in pre-Christian times.

The plaque — measuring approximately nine centimetres wide by eleven centimetres high — had been incorporated into the chapel’s foundation during the ritual blessing that accompanied the laying of the first stone on June 30, 1675. The chapel was established by Marguerite Bourgeoys, one of the pioneers of New France. Bourgeoys, a teacher and lay member of the Catholic Congrégation de Notre-Dame in Troyes, France, arrived in Montreal in 1653 at the request of the island’s French governor, Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve. There she devoted herself to providing free Catholic education both to Indigenous children and to the children of French settlers. Bourgeoys also founded the Congrégation de Notre-Dame in Montreal, the first non-cloistered female religious community in North America.

The inscription on the devotional plaque may have had a personal resonance for Bourgeoys: In her role as one of the colony’s primary administrators, she crossed the Atlantic Ocean seven times before her death in 1700.

When the original Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours chapel was destroyed by fire in 1754, the plaque was salvaged. It was later inserted into a foundation stone of the new chapel that was built in 1771. There it remained until 1945, when it was discovered during renovations of the vault in the chapel’s basement.

At the time of its discovery, the plaque had broken into two pieces, its edges were bent, and mounting holes had been bored into its rim. It was removed from the foundation stone, and the curators of the Marguerite Bourgeoys Historic Site, to which the chapel by then belonged, decided to display it. The plaque was attached to a display mount of padded cardboard, and decorative bronze paint was applied around the edges, in keeping with exhibition practices of the day. No photograph of its reverse side was taken.

When the historic site revamped its permanent exhibition in 2018, it was an ideal opportunity to conduct research and conservation work on some of its most valuable objects that were earmarked for display in the new exhibition spaces. So began the collaboration between the Marguerite Bourgeoys Historic Site and the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI).

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

A special operating agency within the Department of Canadian Heritage, CCI has a team of nearly forty conservators and scientists working to ensure that Canadian heritage collections are preserved and remain accessible today and in the future.

Conservation treatment always begins with assessment and documentation. The plaque underwent a visual inspection, followed by a scientific examination, historical research, and consultations with representatives from the Marguerite Bourgeoys Historic Site.

As part of the scientific examination, and before any conservation work began, CCI took digital X-rays of the plaque while it was still on its cardboard display mount. As the images appeared onscreen, conservators were perplexed by an array of lines that seemed to radiate out from a single point. By manipulating the contrast between lighter and darker areas to achieve clearer images of different parts of the object, conservators discovered that the reverse side of the plaque, hidden by the padded cardboard, contained a different image. It was, in fact, a handcrafted sundial. Since no historical image or account of that side of the object existed, it was a revelation of great significance that raised several questions.

In consultation with historical experts, CCI conservators concluded that the object had served at least three functions over the course of its history: as a printing plate, a sundial, and a devotional plaque. The object most likely began its life in a print shop, probably in Europe, before being repurposed as a sundial in New France, and finally as a devotional plaque inserted into the foundation stone of the Notre-Dame-de- Bon-Secours chapel.

With consent from the Marguerite Bourgeoys Historic Site, CCI opted for a conservation treatment plan that would allow both sides of the object to be visible upon display, with the aim of preserving it and highlighting its value as a witness to the past. The conservator detached the plaque from its padded cardboard backing before cleaning it. The cleaning involved removing the accretions, mortar, and corrosion that obscured the sundial, without damaging the original surface. The conservator built custom tools for the project, which she then used along with dental instruments, micro scrapers, and even a dental drill. Over the course of more than seventy-five hours of painstakingly detailed work under a microscope, the sundial’s outline gradually emerged. Once cleaned, the two parts of the plaque were joined together with a modern adhesive.

The physical restoration work is now complete, and the plaque is on display at the Marguerite Bourgeoys Historic Site in Old Montreal. However, historical research has just begun, and the plaque raises many questions. It appears to have been a printing plate, yet it was present in New France in 1675, when printing was outlawed as King Louis XIV sought to prevent any seditious or revolutionary ideas from circulating. How was it used, and why was it brought to the colony?

The plate was repurposed into a sundial, perhaps to enable missionaries to measure the time between prayers that took place throughout the day. An interesting feature of sundials is that they must be calibrated to a specific geographic location to accurately mark the passage of time. An in-depth investigation of the sundial’s characteristics may therefore reveal some details regarding its origin. The reason for the Latin inscription, with its origins in the works of ancient Roman poets, on this Catholic devotional object remains a mystery.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Heavenly Signs

The plaque found beneath the Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours chapel bears images with many possible meanings.

Mary’s halo of twelve stars is a recurring image in Catholic iconography, but its interpretation has changed throughout the centuries. It may symbolize the twelve tribes of Israel, the twelve apostles, or the twelve graces of Mary, a list of her benevolent and miraculous characteristics.

The rays of light surrounding Mary represent her glory.

The flaming heart pierced by two crescent moons is difficult to interpret. The flaming heart likely represents Mary’s burning love of God. In Catholic symbolism a pierced heart often represents the pain Mary felt during Jesus’s crucifixion, but it is unclear why this heart is being pierced specifically by crescent moons.

The escutcheon is a complex symbol whose interpretation is a matter of debate. The wheat sheaf may symbolize fertility and rebirth, as well as wealth and abundance. The flowers may be roses, often used to represent the beauty and perfection of Mary. The heart and moon may represent the heart of Mary.

The moon is traditionally a feminine symbol that represents fertility, but it can also represent night and death. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, a medieval mystic, saw the moon as a symbol of the Catholic Church: Just as the moon reflects the light of the sun, the Church reflects the light of God.

The dragon represents sin or the Devil. Mary crushes sin by giving birth to Jesus.

The sundial’s place and date of creation are unknown. However, the Jesuits were known to be experts in the creation of sundials. A Jesuit priest may have etched the sundial on the back of the printing plate to keep track of time in a remote missionary outpost.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

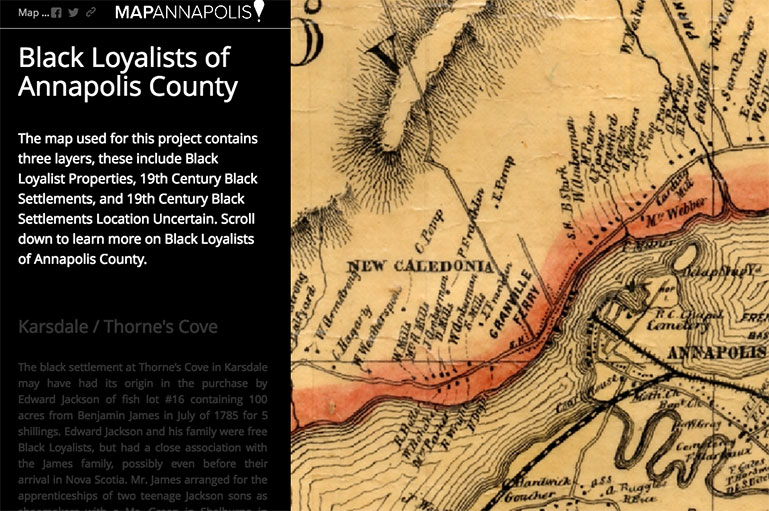

Also in 50 merveilles de nos musées

This special issue of Histoire Canada highlights beautiful treasures from Franco-Canadian communities across Canada. Available in French only.