Oral History: A Museum Treasure

I am a guardian of memories, but I am not an attic. I preserve the beauty of daily life, yet I am not a photographer. I am surrounded by words and stories, but my library contains no paper. I am a curator of people’s memories, of emotions and experiences.

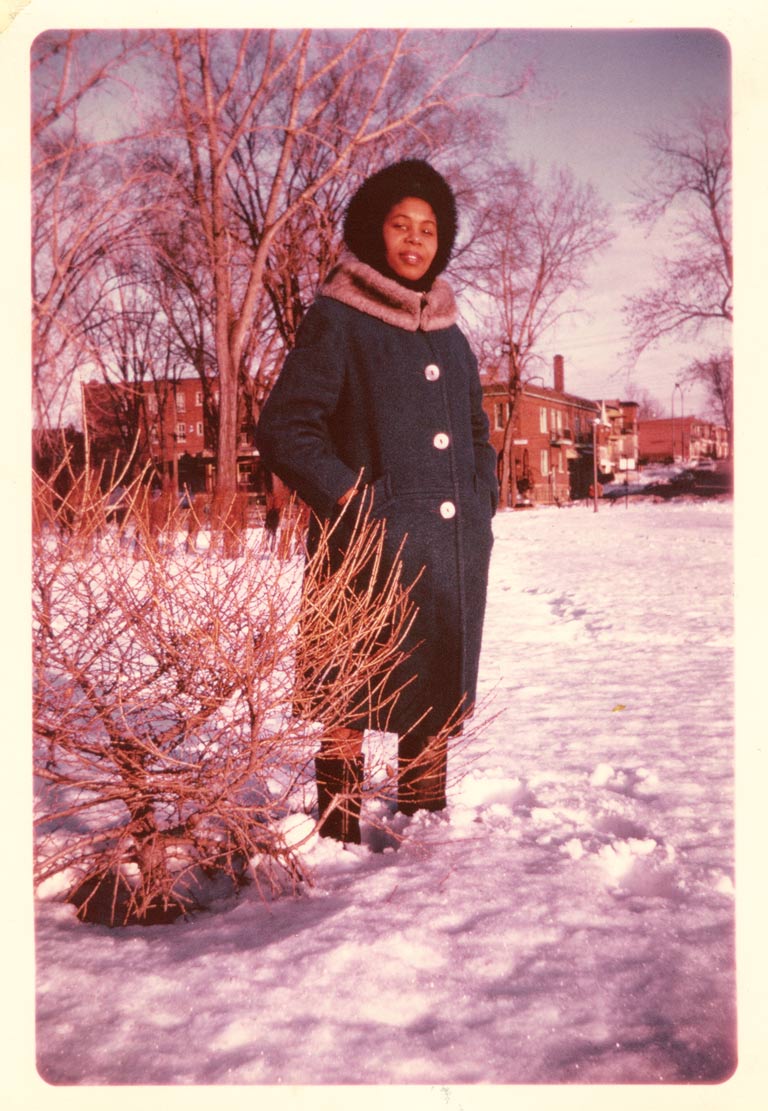

As a witness to the passage of time in Montreal, the vaults of the MEM — Centre des mémoires montréalaises hold not only objects and images that remind us of the popular history of the past century, but also a precious collection of first-hand testimonies. To tell the story of Montreal and its various identities, the MEM devotes considerable attention to citizens’ memories — a mosaic of lives that gives the city its own unique colour. Listening to these memories gives us the privilege of witnessing a moment — or a whole era — from the point of view of those who lived it.

The MEM is the successor to the Centre d’histoire de Montréal (CHM), the museum of the City of Montreal founded in 1983. The CHM team began working with oral histories in the early 2000s. The first history-gathering projects took the form of “memory clinics,” during which citizens were invited to tell stories of their neighbourhoods, of life in their, or of their own personal journeys. Conducted in association with community organizations, these initial gathering activities were carried out with a view to exhibition rather than preservation, and with the goal of fostering community involvement and developing collective pride around a shared history.

With the success of these activities, the CHM became one of the few museums at the time to showcase oral history through the collection and presentation of first-hand accounts. Under the leadership of Jean-François Leclerc,the museum’s director from 1996 to 2018, the CHM team sought out Montrealers to recount the stories of their neighbourhoods — whether Rosemont, Parc-Extension, or Saint-Laurent — share their experiences as part of an immigrant community —such as the Portuguese, Haitian, or Chinese communities — or give their perspectives on daily life in social housing complexes like Benny Farm and Habitations Jeanne-Mance.

Ready for a new challenge, the CHM team then embarked on a series of major projects involving the further gathering of first-hand accounts, which resulted in several successful exhibitions: Lost Neighbourhoods (2011-2013); Scandal! Vice, Crime and Morality in Montreal, 1940-1960 (2014-2017); and Explosion 67 – Youth and Their World (2017-2020). With the living word at the core of the experience, these exhibitions evoked powerful emotions, as visitors made connections between the oral testimony and their own personal histories, and learned about Montreal history from the mouths of their neighbours.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, the CHM team was advancing museology and working hard to have oral testimony recognized as a legitimate object of a museum collection. From 2016 to 2019, cassettes and discs of the CHM’s first collection projects — notably those involving the Portuguese and Haitian communities, the inhabitants of Rosemont and Benny Farm, and the staff at Lovell printing — were saved from the basement and from oblivion. They were digitized, copied, indexed, and catalogued. This rescue-and-description operation was undertaken so that these rich oral resources could be reused in new MEM projects and made available to researchers interested in the details of daily life, marginalized stories, and lived experiences.

The initiative is already bearing fruit — take, for example, Fenêtres sur l’immigration (Windows on Immigration), a travelling exhibition that focused on immigration stories and that was produced using first-hand accounts from the CHM collection, gathered for various projects over the years.

Oral history encourages us to look beyond the first story we hear and to explore different perspectives, giving us access to various layers of the Montreal experience. Listening to these accounts prompts us to put our own prejudices aside, to practice humility and empathy, to better understand the reality of others, and to open ourselves to worlds that we did not know existed.

“[It was] a time when nothing was permitted for gays. You have to understand that, until sixty-nine, we were illegal. We were illegal in every manner, in every way. And a gay bar,like the one I helped to create, the continuation of the Samovar at 1422 Peel — in 1957-58, two hundred and fifty homosexuals in the same place, that was practically considered to be a brothel you could say, it was an illicit place, because we were all illegal. All of us. Until sixty-nine. They could arrest us. We were considered third-class citizens, no more, no less. (...) People looked left and right, and even up, before going into a bar.”

– Armand L. Monroe

Though it does not claim to be an exhaustive representation of Montrealers’ experiences, the MEM’s collection of first-hand accounts ensures that stories worth telling are saved from falling into oblivion. The first-hand accounts in this collection are the voices of the communities, neighbourhoods, households, and trades of Montreal; they add levels of complexity to our portrait of the city’s history. In making the decision to preserve and catalogue first-hand accounts as objects in its collection, the MEM is expressing its willingness to value witnesses as experts in their own lived experience, and positioning itself as the keeper of Montrealers’ memories.

As part of the MEM, the oral history collection has the potential to add an emotive and authentic dimension to Montreal’s history. It is a collection thatcomprises interviews with witnesses to distinct events, places, and eras, sharing their recollections, emotions, and interpretations of the past. The collection also includes a small number of interviews with expert historical researchers:These types of interviews have the advantage of making historical context much more dynamic than a simple panel of text.

“I didn’t leave Algeria because I wanted to. Not because I was poor. Not because I didn’t have any money. Not because I no longer loved my country or its people. But because I was afraid. I was afraid for my children, for my husband, and for myself.”

– Jeanne Farida

Today headed by Annabelle Laliberté, the CHM has undergone a major transformation to become the MEM, a citizen-focused museum, that recently opened its doors at the corner of Sainte-Catherine Street and Saint-Laurent Boulevard. Carrying on the legacy of the CHM, the MEM has a revitalized mission to celebrates Montreal’s identities, voices, and memories. The MEM’s collection of first-hand accounts will play a key role in the implementation of this mission. In fact, it was in large part the desire to preserve, develop, and showcase this collection that motivated the MEM to create a new curatorial position in 2019.

The living memory preserved at the MEM covers nearly a century, going back to the 1930s. Today, the collection includes 538 interviews with 557 witnesses representing over 410 hours of audio and audiovisual interviews in five languages. And the collection continues to grow. In the summer of 2021,new oral testimonies were gathered in the Milton-Parc neighbourhood using the MEM’s citizen bikes — cargo bikes equipped with portable recording studios. This and other initiatives make the MEM the ideal place for Montrealers to meet and tell their stories.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement