Out of Everyday Life, Into the Museum

Everyday objects and popular culture hold pride of place at Quebec’s Musée de la civilisation.

As in all museums of social history, these artifacts shed light on the past and raise questions for the present. They are integral to the Museum’s program of acquisitions and collections: to bear witness to the material culture of the residents of Quebec. Encompassing all sectors of human activity — from domestic life to the working sphere, through communications, leisure, and many other realms — it is truly a colossal undertaking. And despite the impressive volume of objects in the collections, there are gaps left to fill in order to better document society’s past and its constant evolution.

As a curator, I am faced with several questions. How do we reconcile our fast-growing collections with our limited storage space? Which ordinary objects should we choose to preserve? These are questions that become even more profound when they concern contemporary objects, questions I would like to further explore by examining a few recent acquisitions.

Narrowing down the selection

The decline in religious communities in the second half of the twentieth century led to a major donation from the Soeurs de la Charité de Québec (Sisters of Charity of Quebec). The donation’s purpose was to “provide an account of the community’s history, its works, and its spiritual influence.” In all, more than 4,000 objects, along with the community’s archives, were acquired. Because they are part of a coherent and documented whole, the common objects paint a detailed portrait of the community’s daily life and its major contributions to Quebec society in the areas of education, health care, and social services.

The objects selected meet the museum’s stated goal. The usual selection criteria — in particular, the objects’ representativeness, polysemic qualities, and state of preservation — were applied as part of a “generous” approach to acquisition. But if other religious communities come knocking at the museum’s door to request the preservation of their heritage, how will we answer them? Space constraints and the need to maintain balance in the collection will limit acquisitions. Given our inability to pass on everything to future generations, we bear the responsibility of choosing wisely. I often have doubts. Despite regularly updated analytical tools, policies, and procedures, a degree of subjectivity remains.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Amplifying voices

Today, as never before, museums seek to reflect the lifestyles of all citizens. They have opened themselves up to ethnocultural, socio-economic, regional, religious, sexual, generational, and bodily diversity. At the Musée de la civilisation, the recent acquisition of objects from Lauberivière homeless shelter makes space for a socio-economic group that was previously absent from the museum’s collections: people experiencing homelessness. Though the objects acquired may at first appear to be of limited interest — salvaged furniture, a telephone, a shopping cart, for example — they take on meaning when paired with accompanying testimonies. They were selected in the course of a co-creation process that included people with lived experience, facilitators, and the museum’s team.

This example illustrates how seemingly mundane objects can reflect social realities when their human dimension is revealed through stories. Yet, the importance of intangible heritage such as this leads me to cast a critical eye on past acquisitions, which often arrived in bulk and were poorly documented. What do we do with the thousands of silent objects piled up in storage? Should we simply ignore them, or should they be replaced with comparable, but better-documented objects?

I believe it is wiser to document the existing objects retroactively, bit by bit. Of course, this approach does not provide access to personal accounts, but basic information about a given object — such as its function, its age, and the name and history of its maker — are essential to elucidating it. It is a huge undertaking, and we must give ourselves time to do the job.

Transferring objects out of the collection is considered, with prudence, for objects in poor condition or those of which we have multiple examples. Is it necessary to keep 800 hand planes? I’m not sure. Though it might be hard to imagine such an acquisition today, serial collecting is part of the collections’ history.

“These long scissor-arms allowed me to greet loved ones with bursts of laughter, while keeping to recommended distance of two metres apart. But nothing will replace direct contact and human warmth.”

– Aline Bernier

Taking the long view

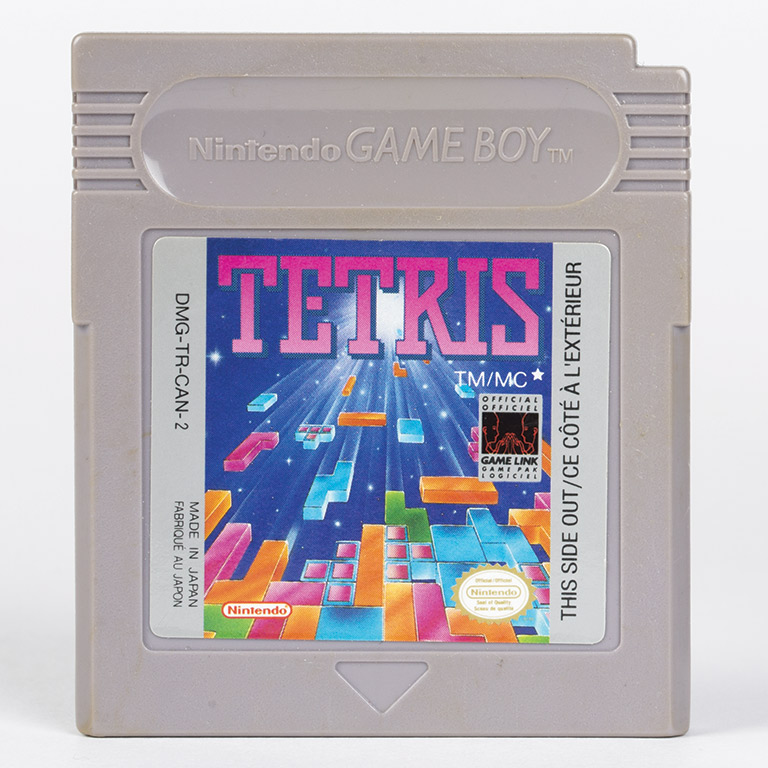

The social impacts of rapid technological evolution are an area of contemporary concern for the museum. To coincide with the exhibition A History of Video Games, the Museum put out a public call for donations of video games and game consoles. What games and consoles should be acquired from among the wide array sold since the 1970s? The Museum prioritized the most popular in Quebec and teamed up with experts to identify which pieces to acquire. In all, 38 games and 14 consoles were added to the Museum’s collections.

This collection created via citizens’ contributions was a first for the Museum. The household presence of video games and the opportunity to gather testimonials motivated this choice. I found it stimulating to formulate specific acquisition objectives, as the development of collections is generally subject to donation offers. What stands out for me is that the ideal concept for a collection should always precede an analysis of acquisition proposals.

In 2020, a broader gathering from citizens was carried out to bear witness to the COVID-19 pandemic. Proposals were sorted based on categories established after their reception. Canning jars, a dog collar, and facemasks—with their accompanying stories—were among the items selected. The whole attests to the population’s adaptability and creativity. While the lack of objectivity is flagrant, we could not pass up the opportunity to gather direct traces of this event. I wonder if our successors will share this point of view!

Getting back to the initial question: “Should ordinary objects be preserved?” My answer is “Absolutely.” The choices, however, must be exemplary and justified. In making their way into the Museum, the objects acquire a particular status, a heritage character, whether certain or in-the-making. In his essay The Contemporary Museum Object, An “Object Without Qualities?” French museologist and sociologist Jean Davallon rightfully emphasizes: “The contemporary artifact is more than just the sum of its materiality, it documents a portion of social life, which is the actual object to be made part of our heritage.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Also in 50 merveilles de nos musées

This special issue of Histoire Canada highlights beautiful treasures from Franco-Canadian communities across Canada. Available in French only.