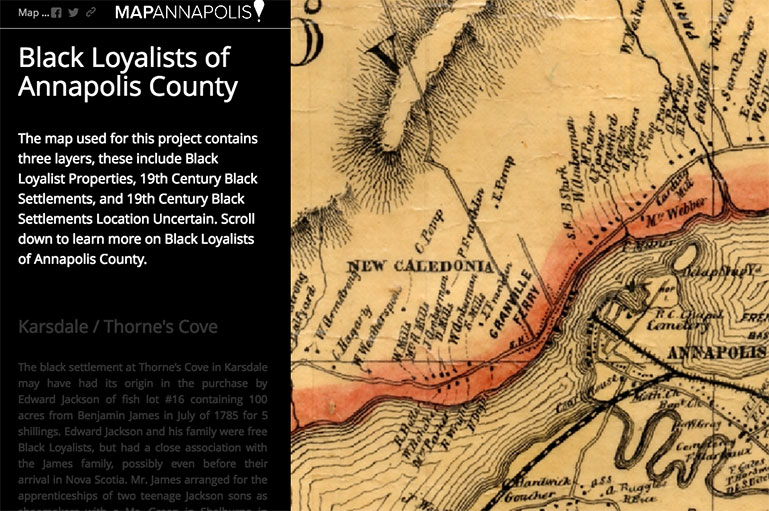

The Polio Epidemic in Canada

Long before the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 began its spread and stoked fear and anxiety across the globe, another lethal disease advanced rapidly and caused terror both worldwide and here in Canada.

The article “The Twentieth-Century Plague,” which appeared in the April-May 2004 edition of The Beaver, explains how poliomyelitis (polio) spread in Canada and brought horror to families.

The first reported case of polio in Canada, according to the story, was in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1910, when a young girl became ill with the disease and died while in hospital. The virus soon spread to other Ontario communities, including Toronto, Windsor, and Niagara Falls.

As years passed, polio’s toll on the population grew. In 1937 alone almost 4,000 cases were reported in Canada, with 2,546 cases and 119 deaths reported in Ontario that year.

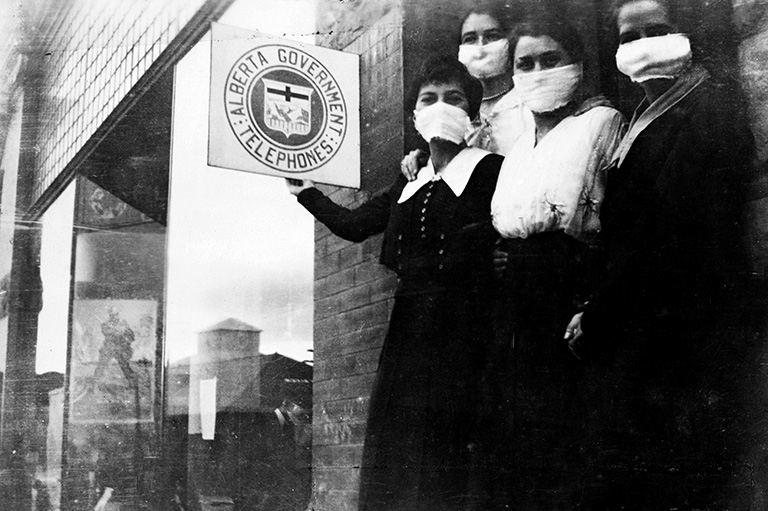

Quarantines have become commonplace around the world in 2020 in an attempt to slow the spread of the new coronavirus. Similar tactics were used during the early days of the polio epidemic. Public health departments in Canada quarantined the sick, closed schools, and restricted children from travelling to locations such as theatres.

Although the disease caused death, disruption, and fear it also caused Canadians to go to great lengths to find ways to help the ill and save lives.

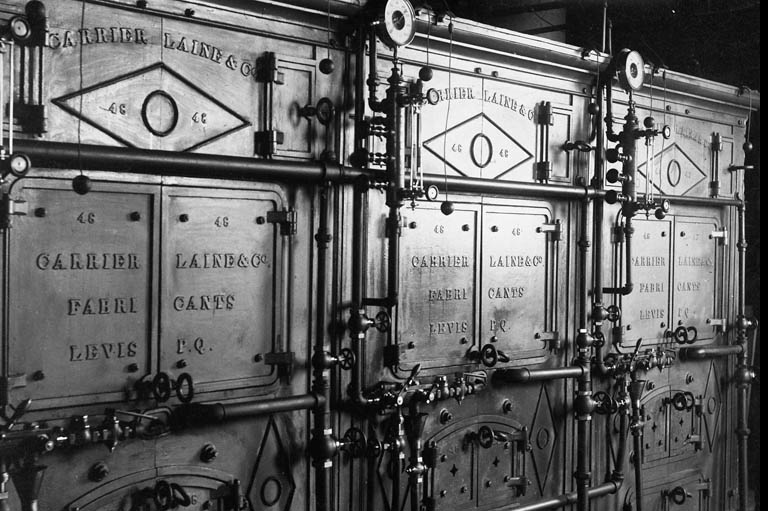

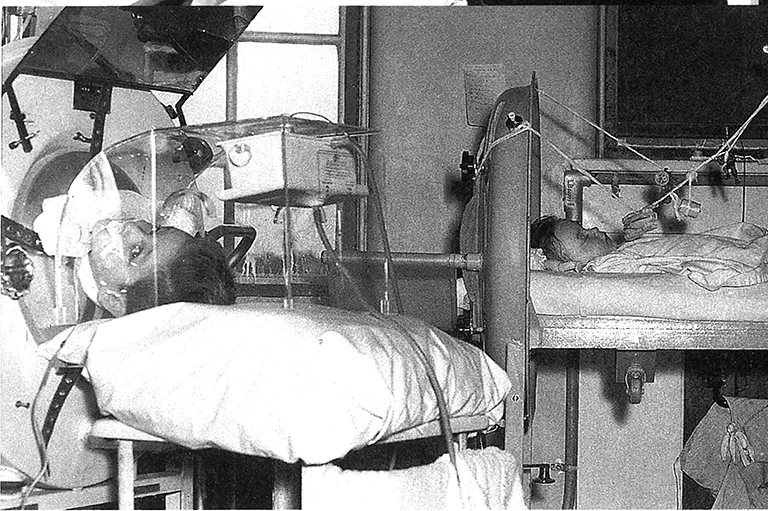

In 1937, only one iron lung — a mechanical respirator needed by some polio patients that enabled them to breathe on their own — existed in all of Canada. When a boy was admitted to Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children that year with breathing problems, doctors and engineers sprang into action and saved the boy’s life by building a wooden iron lung-style device. They used plywood and an experimental respirator that had been created to treat premature infants.

Over the next six weeks, hospital workers constructed an additional twenty-seven iron lungs in the hospital’s basement and rush shipped them to wherever they were needed in Canada.

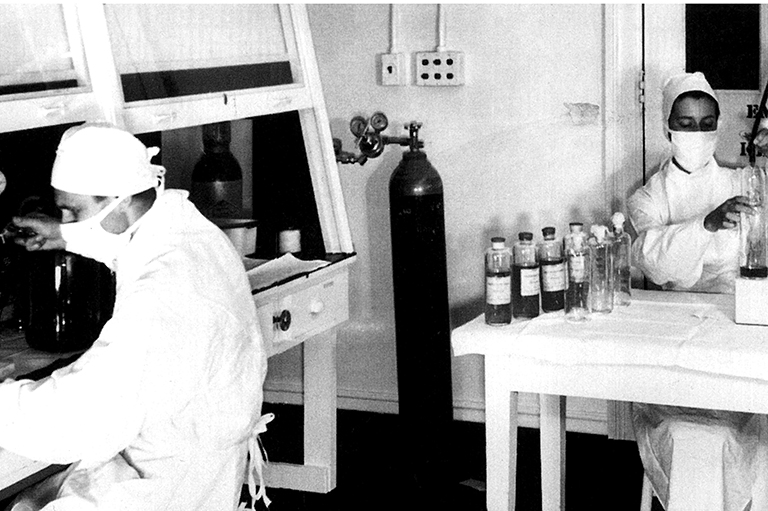

Canada also had missteps when it came to treating polio. A nasal spray designed to block the virus from entering the body was used on five thousand Toronto children in 1937, but it was soon abandoned. It didn’t prevent polio and it caused several of the children to permanently lose their sense of smell.

While polio cases declined in Canada during the Second World War they increased substantially after the war. The number of cases reached a peak in Canada in 1953 with nearly nine thousand cases and five hundred deaths, the most serious national epidemic since the 1918-20 Spanish influenza pandemic.

The widespread application of the Salk vaccine in 1955 and the Sabin oral vaccine in 1962 eventually brought polio under control in the early 1970s, but Canada was not certified polio-free until 1994.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!