Outlaws

James H. Gray, a trail-blazing chronicler of the manners and mores of the people of the Prairies, once quipped that historians had led him to believe only “monks, eunuchs, and vestal virgins” settled the Canadian West.

To explode the myth he wrote a dozen books documenting aspects of Western social history — most famously, whoring and boozing — that had never before been closely examined.

Since that time, other historians, taking their cues from Gray, have shown how the West attracted hundreds of individuals who lived beyond the boundaries of convention and the confines of the law.

The fur trade spawned the first of them. One of the most notorious was Peter Pond, a pugnacious Yankee who killed a fur-trading rival in a duel before moving in 1775 to the northwest.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

By 1779 he had formed a loose coalition with other independent traders who called themselves the Nor’Westers. Pond became their agent in the Athabasca region of what is now northern Alberta, where he was one of the first non-Indigenous people to see evidence of the oil sands deposits that now form the richest energy reserve in the world.

Athabasca was a lucrative fur-trading district for Pond. Word of his success spread to Montreal, headquarters of the Canadian fur trade, and that brought him some competition. His contemporaries both admired and detested him. Explorer David Thompson summed it up best, saying: “He was a person of industrious habits, a good common education, but of a violent temper and unprincipled character.”

One of his rivals was Jean-Étienne Waden (or Waddens) — a man described by explorer Alexander Mackenzie as being of “strict probity and known sobriety.” Waden encountered Pond at Lac La Ronge (in present-day northern Saskatchewan) in 1782.

According to Mackenzie, “Mr. Waden had received Mr. Pond and one of his clerks to dinner; and in the course of the night, the former was shot through the lower part of the thigh, when it was said that he expired from the loss of blood.” Two years later, when Pond was next in Montreal, he appeared before a judge and was apparently acquitted.

Pond’s next homicidal encounter, with a rival named John Ross in the Peace River country in 1786, also resulted in no charges. But that was the last straw for his fellow Nor’Westers. They fired him at the end of 1787 and sent him packing back to the United States, where he fell into poverty and died in 1807.

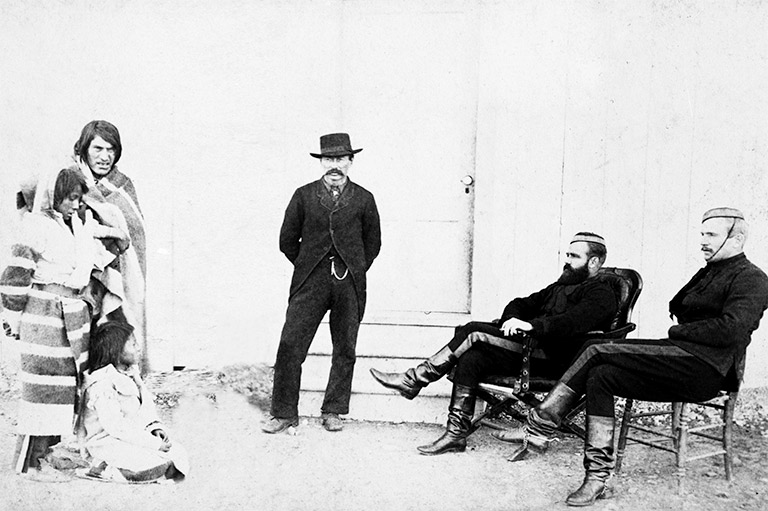

By the 1870s, the fur trade was in decline and the whisky trade was thriving. Three hundred Mounties rode west in 1874 to put the whisky traders out of business.

Because of an inaccurately drawn map from the 1857 Palliser expedition, they ended up in Fort Benton, Montana, three hundred and fifty kilometres south of their intended destination. But they were fortunate to encounter Jerry Potts, a Métis guide who knew the territory well.

Advertisement

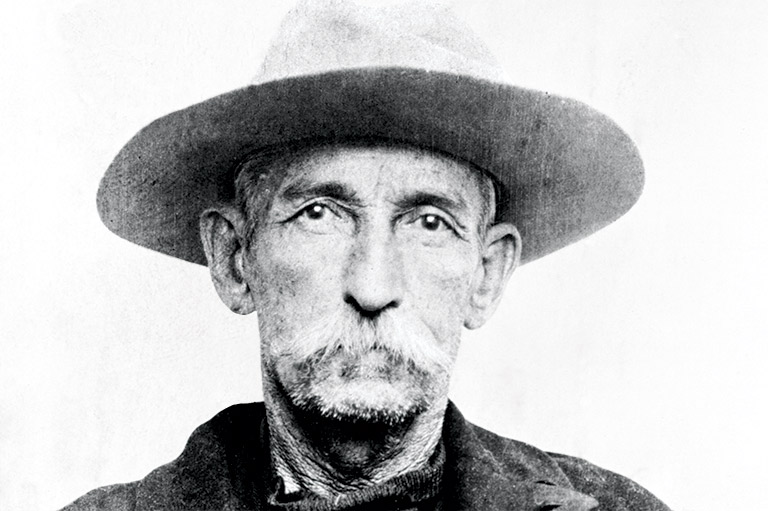

Potts was one tough individual. The son of a white father and a Blackfoot (Blood) mother, he grew up at Fort Benton, where he learned how to drink, gamble, and shoot a pistol. In his early twenties he got into a bar fight, shot the man to death, and then coolly finished his bottle of red-eye whisky.

No charges resulted, mainly due to a lack of local law enforcement. Twenty years later, while working as a hired hand for whisky traders in southern Alberta, Potts killed a trader who had murdered his mother and half-brother.

No charges resulted there, either. After that, Potts worked to end the whisky trade in Canada. He helped the Mounties establish Fort MacLeod, Alberta’s first police post, and spent the rest of his life working for them as a special constable.

After his 1896 death, which was brought on more quickly by alcohol abuse, he was remembered more for his frontier skills and ability to smooth over relations between the Mounties and the Blackfoot than for his earlier bouts of violence.

The Macleod Gazette and Alberta Livestock Record mourned his loss, saying he had “made it possible for a small and utterly insufficient force to occupy and gradually dominate what might so easily, under other circumstances, have been a hostile and difficult country.”

Whisky and furs were certainly powerful attractions for criminal types in the early West. But nothing was more enticing than gold.

In the Cariboo country of present-day British Columbia a notorious Kentucky serial killer named Boone Helm was implicated but never charged in the robbery and murders of three miners in July 1862. Also known as the “Kentucky cannibal” for his practice of eating the flesh of his victims, Helm showed up in Victoria on Vancouver Island a few months later and was arrested for failing to pay his bar bill. After serving a short sentence, he was let go.

The following spring he was arrested again at Fort Yale in the Fraser Canyon. This time he was turned over to American authorities.

On the eastern side of the Rockies, the legend of a lost cache of tainted gold still lures fortune seekers. The story begins in 1870 with prospector Frank Lemon, a Montana blacksmith. While accounts vary as to where Lemon found the gold, he apparently hid his stash in the Crowsnest Pass region of present-day southern Alberta.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

According to an account by Canadian Senator Dan Riley, who died in 1948, Lemon killed his prospecting partner with an axe blow to the head after finding the gold. He then fled back to Montana and confessed his crime to a priest, who dispatched a parishioner to Alberta to bury the body and mark the spot with a mound of stones. Riley said local First Nations removed the stones and obliterated all traces of the murder.

While Lemon was able to sketch from memory what he said was a rough map of the area, he was never able to find the spot again.

The search for what became known as the Lost Lemon Mine continues to this day. Old-timers tell the story to their grandchildren, Crowsnest Pass drugstores sell books chronicling the tale, and a local campground proudly bears the name Lost Lemon R.V. Park.

Rumours also persist today that a stash of gold and cash lies buried near Golden, British Columbia, in the eastern Rockies. The loot was stolen in 1884 by a gunman who, without warning, fired at three men on horseback, killing one and wounding another.

The gunman was “none other than Bulldog Kelly, a big, red-haired, loud-mouthed character from the States,” according to British Columbia author T.W. Patterson.

After an extensive manhunt, Kelly fled to the United States and was eventually arrested in Minnesota. But attempts to extradite him back to B.C. failed because his Irish lawyer apparently had influential friends in high places. Kelly never returned to collect his ill-gotten booty.

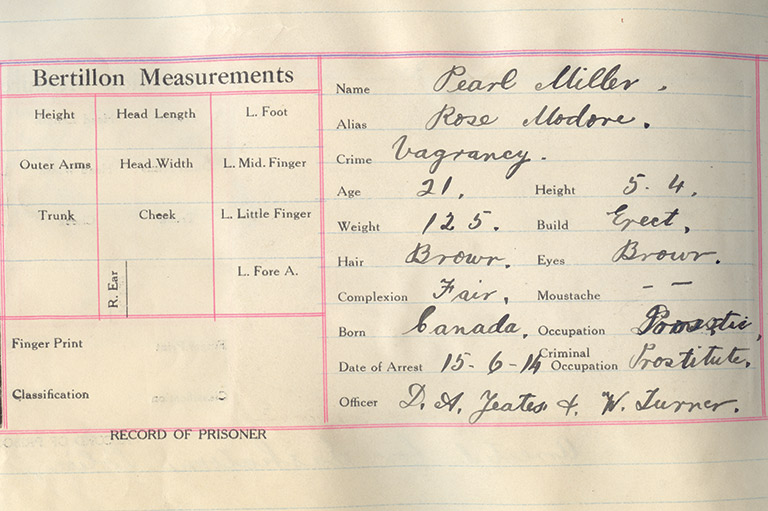

Women also flouted the law. In the late nineteenth century, sex workers set up prostitution tents at construction camps along the railway line and invariably remained in town after the railway workers moved on.

By the early 1900s, as Gray recounted in his book Red Lights on the Prairies, prostitution was a thriving business in the West.

One of the more colourful characters Gray came across was a Calgary madam, Pearl Miller, who achieved semi-legendary status because of a story that circulated after the Second World War. It told how some Canadian soldiers camped next to an American regiment on the eve of the Normandy invasion.

According to the legend, the Americans put up a sign reading, “Remember Pearl Harbor.” The Canadians responded with their own sign: “To hell with Pearl Harbor, remember Pearl Miller.”

Miller, an American, came to Calgary just before the First World War. She eventually set up a brothel in an exclusive residential neighbourhood, where the business became renowned for its cleanliness and lack of rowdiness. Police were intent on putting her out of business, however, and in 1941 she was sentenced to three months in prison.

Arresting officer Jock Ritchie recalled that Miller was always extremely polite with the police, even after her arrest.

“She seemed to take it for granted that you were on the one side of the fence and she was on the other,” said Ritchie. “And she never seemed to bear any grudges against us.” After her release from jail, she became a social worker of sorts, counselling women to leave the sex business behind.

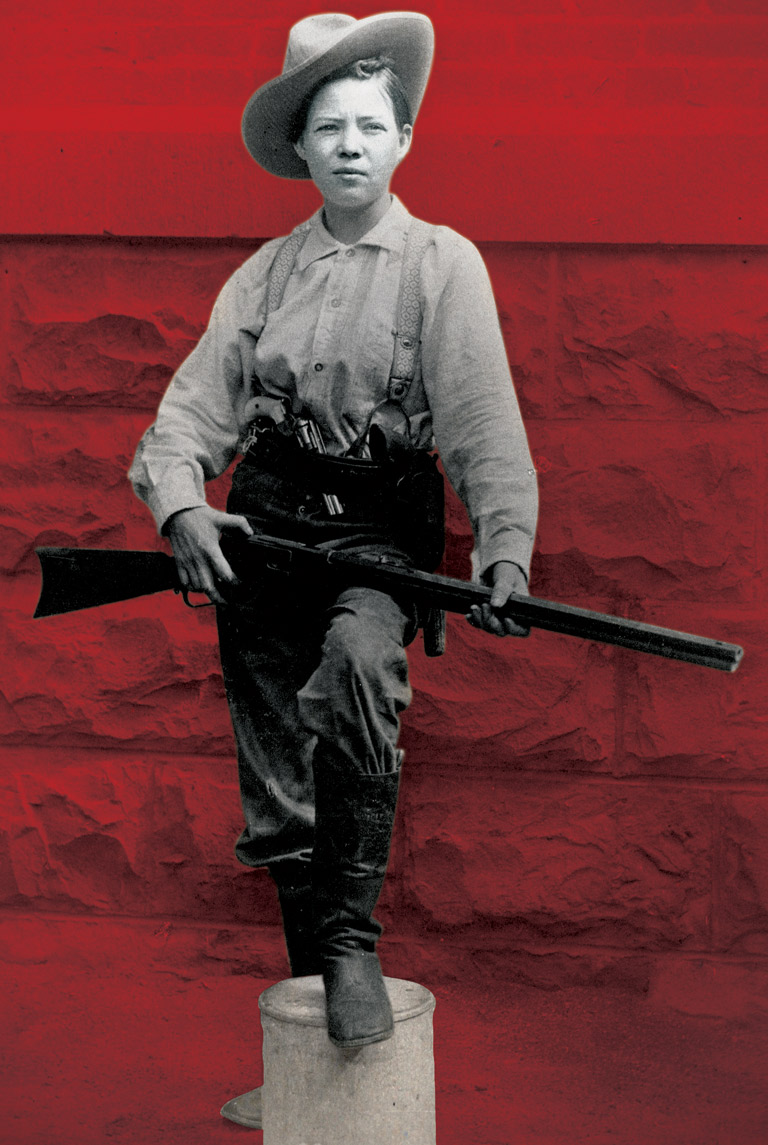

Meanwhile, another woman by the name of Pearl — Canadian-born Pearl Hart — made her mark as one of the few female stagecoach robbers in the American West.

Born in Lindsay, Ontario, as Pearl Taylor, she eloped at age seventeen with a charming gambler named Frederick Hart. In 1893 they visited Chicago’s Columbian Exposition, where she became entranced by the Wild West shows and the legends of the Old West.

Her gambling husband turned out to be a no-good drunk and an abuser; she left him in 1895 and made for Phoenix. When she learned in 1899 that her mother was seriously ill and needed money for medical care, Hart decided to evoke the spirit of the West by robbing a stagecoach.

She dressed up as a man and carried out the robbery with the help of a male accomplice. They collected about $450, rode into the hills, and promptly got lost. They fell asleep by a campfire and awoke to find themselves surrounded by a posse.

Hart served eighteen months for her crime. During that time she attained minor celebrity status as “the lady bandit,” drawing admirers to the jail to get her autograph.

After her release she tried to capitalize on her notoriety by starring in a stage play her sister wrote about her Western adventures. But her fame faded quickly, and Hart disappeared from public view.

The Full Story Behind the Lady Bandit

Advertisement

With the coming of the railways came Western Canada’s first train robbery in 1904. Staged at a railway junction sixty-five kilometres east of Vancouver, the robbery was masterminded by a soft-spoken American outlaw named Bill Miner. Miner and his two accomplices got away with $6,000 in gold dust and $1,000 in cash.

Dubbed “the gentleman bandit” because of his polite demeanour during holdups, Miner was credited with inventing the phrase “Hands up!” He had spent more than thirty-five years in American prisons for stagecoach robberies before moving north to B.C. when he was about sixty years old.

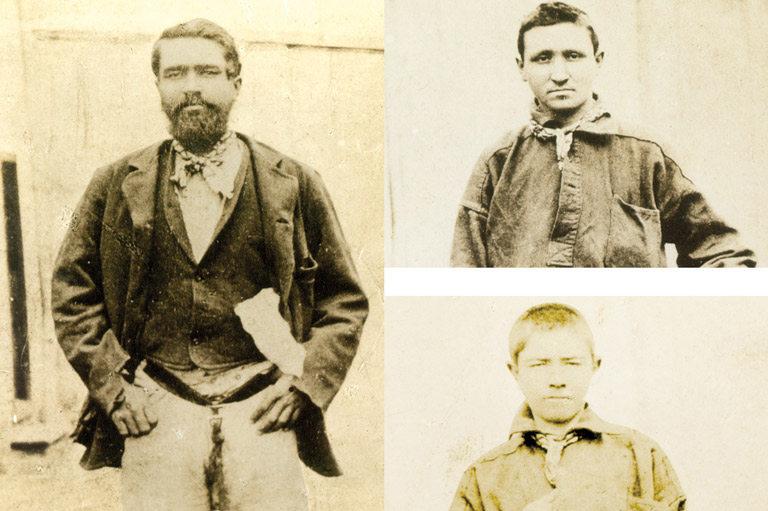

Miner was never accused of murder. The same cannot be said of Ernest Cashel and Jack Krafchenko.

Cashel came to present-day Alberta from Kansas in 1902. Arrested in Ponoka on a forgery charge, he escaped and fled south to Lacombe, where he took shelter with a rancher.

He was convicted of murder after the rancher’s body was found in a river. Cashel was sentenced to hang in December 1903.

His brother visited Cashel in prison, ostensibly to say a last, tearful goodbye. As both men wept, two loaded revolvers were slipped through the bars.

Cashel ordered the guards to unlock his cell and escaped into the night. Police immediately launched what the Calgary Herald called “the greatest manhunt in the history of the Territories.”

Despite what appeared to be his obvious guilt, his lawyer, Paddy Nolan, portrayed Cashel as a fundamentally good kid who got in with the wrong crowd: “But he’s smart — too smart for the police he outwitted and embarrassed — and he’s got a first class sense of humour. And in case it escaped your notice, Cashel is a good Irish name.”

Cashel was on the run for forty-five days. Police tracked him to a farmhouse near Calgary, and he surrendered when they threatened to burn it down. He went to the gallows at age twenty-one, leaving a note urging other young men not to follow in his criminal footsteps.

“Take my advice, dear boys, and stay at home, shun novels, bad company, and cigarettes. Don’t do anything, boys, that you are afraid to let your mother know.”

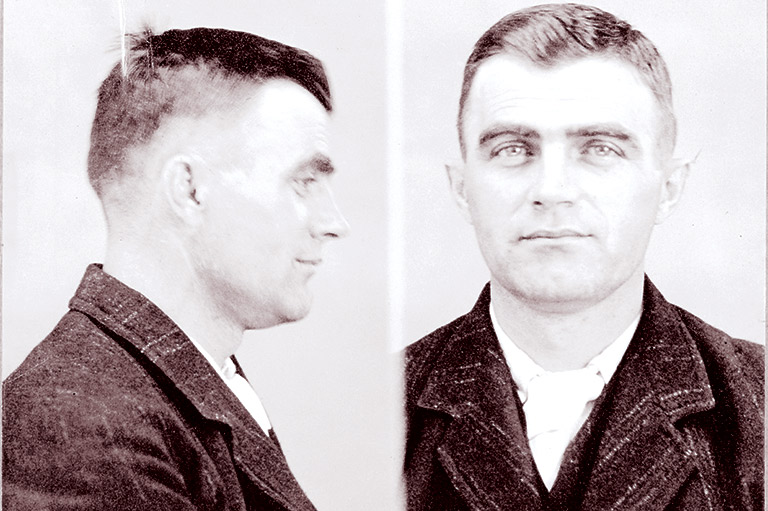

Krafchenko, like Cashel, began his criminal life as a thief and cheque forger. He came from Plum Coulee, Manitoba, and, after roaming North America as a sometime professional wrestler and two-bit criminal, returned to Plum Coulee in November 1913 to hatch his last big heist.

He robbed the local bank, pocketed $4,700 in cash, and shot the bank manager to death when he tried to stop Krafchenko from getting away. Krafchenko fled to Winnipeg and was arrested without struggle one week after the Plum Coulee incident.

While in jail, Krafchenko smooth-talked his lawyer and a prison guard into helping him to escape; both were mesmerized by his tale of possessing fabulous wealth that he would share with them when released. He was at large for eight days before being recaptured.

Represented by another lawyer after the accomplice lawyer was disbarred and jailed for three years, Krafchenko was convicted of murder in April 1914 and hanged in July. His execution was the last big event to engage Manitobans before the outbreak of the First World War.

The war brought Prohibition to Alberta, and by the 1920s, according to provincial Attorney General John Boyle, bootlegging generated an economy of more than seven million dollars annually.

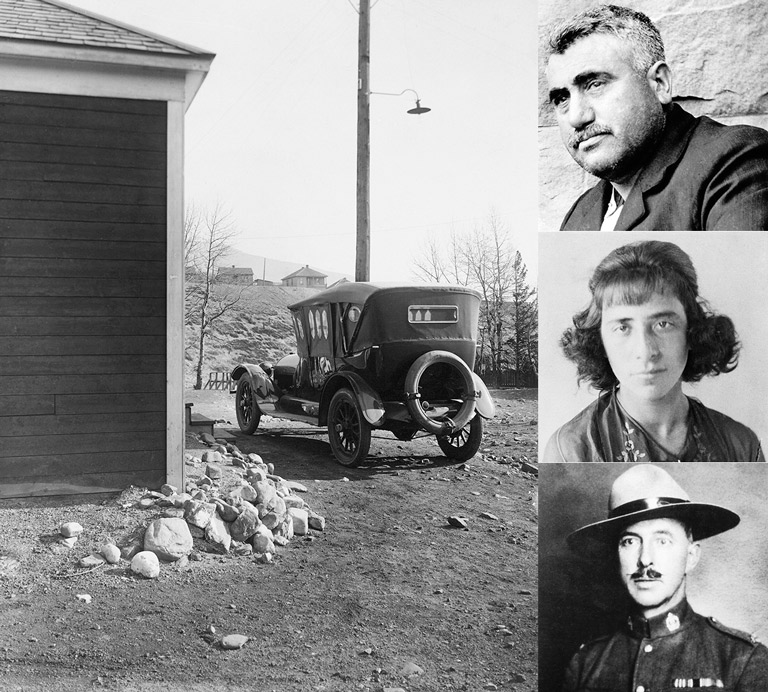

One of the most successful bootleggers was Emilio “Emperor Pic” Picariello, who operated a Crowsnest Pass hotel as a front for running liquor from British Columbia to Montana.

During one such booze run in September 1922, Picariello’s son was shot and wounded by Constable Steve Lawson at a police checkpoint. Picariello vowed revenge against Lawson and drove to the barracks to confront him. He was accompanied by a hotel employee, twenty-two-year-old Florence Lassandro.

Shots were fired, and Lawson lay dead in the street with a bullet in his back. Who actually fired the fatal shot was never made clear. Lassandro initially confessed but later said she had only agreed to do so in the belief that authorities would never execute a woman.

Picariello and Lassandro were both convicted of murder and sentenced to death. Prime Minister W.L. Mackenzie King was bombarded with petitions urging that Lassandro’s sentence be commuted to life imprisonment. But others, such as suffragist Judge Emily Murphy, wanted the sentence to stand; otherwise, other criminals would use women to commit murder with impunity.

After two brief reprieves, both were executed on May 2, 1923. Lassandro, the only woman every hanged in Alberta, went to her death protesting her innocence to the last.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.