Reconsidering the Gold Rush

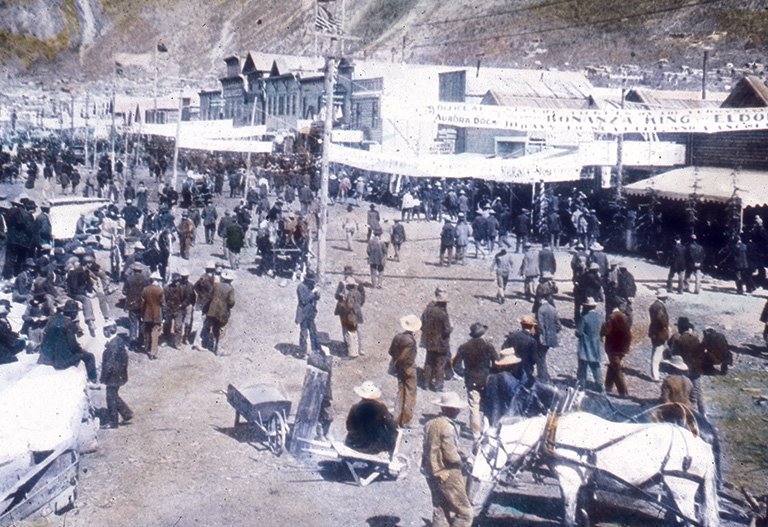

The Klondike gold rush is one of the most mythologized events in Canadian history. One hundred and twenty-five years ago, a handful of prospectors discovered gold nuggets in a tributary of the Klondike River and triggered a stampede of more than one hundred thousand people into Yukon. They travelled thousands of kilometres to reach the district, then rafted down the Yukon River and established a mining camp on a mud flat. The visuals and soundtrack of this epic adventure are embedded in the national imagination. The hair-raising climb up the Chilkoot Pass! (Flash the famous Eric Hegg photo onscreen.) The brutal conditions in which tens of thousands of prospectors lived! (Show grainy archival photos of a crowded Front Street in Dawson City.) The bars, casinos, dancehalls! (Cue the cancan music.)

The excitement ebbed after three years, and most of the prospectors moved elsewhere. But the appetite for gold rush tales of derring-do has continued to be fed by writers from Jack London to Robert Service, from Pierre Berton to ... me. In 2010 I published Gold Diggers: Striking It Rich in the Klondike. I told the story of the gold rush through the lenses of six individuals who were there and whose voices I was able to recover through written records — letters and memoirs plus archival newspaper photos and clippings. I was keen to show that the episode involved far more people than the muscular, grizzled heroes celebrated by previous writers. So, in addition to a miner, I wrote about a saintly priest, a spit-and-polish Mountie, a savvy businesswoman, a female reporter from the London Times, and the young Jack London who built his astonishingly successful career on stories based on his Yukon experiences.

But, in the decade since I published that book, I’ve realized that my account of the Klondike gold rush was unbalanced. If I were to embark on such a tale again, I’d amplify my approach. The way we understand the past evolves continually, but recently there have been two particular (and overdue) shifts in the stories we tell ourselves about past events.

The first is the recognition that textbook Canadian history has always focused on settlers. For too long, we have ignored, disparaged, or challenged the stories of Indigenous people who lived on this land for thousands of years before Europeans arrived here. As former Senator Murray Sinclair, who headed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, put it, “We need to change the way that we educate our children. Indigenous and non-Indigenous, they all need to grow up and be educated in a Canada with a fuller and more proper sense of the history of this country.” That means much more thorough and respectful coverage of Indigenous history. Lee Maracle, the celebrated poet who is a member of the Sto:Loh Nation, insists, “Nothing about us, without us.”

The second shift is the greater attention being paid to environmental history — the study of human interaction with the natural world. Climate change forces us to reconsider the colonial assumption that the earth’s resources are inexhaustible and are ours to exploit. In the words of the fierce young climate activist Greta Thunberg, “Our house is on fire.” If we are to prevent the planet from becoming unlivable, we need to develop a more holistic approach. As Chief Dana Tizya-Tramm of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation in Old Crow, Yukon, told the 2018 Global Climate Action Summit, “Respect for Indigenous rights is key to stemming and reversing climate change.... The disregard of our people is the disregard of this planet.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

I recognize now that the gold rush story is incomplete without these two perspectives. I want to re-establish the pivotal role of Indigenous people in the events on the Klondike River during the 1890s. Even the name of the river itself is a colonial corruption of a much older name — Tr’ondëk, the name of the First Nations people who had lived in the region for thousands of years. The Tr’ondëk chief of the time played a significant role in the gold rush but has been pushed aside in the conventional stampede narrative.

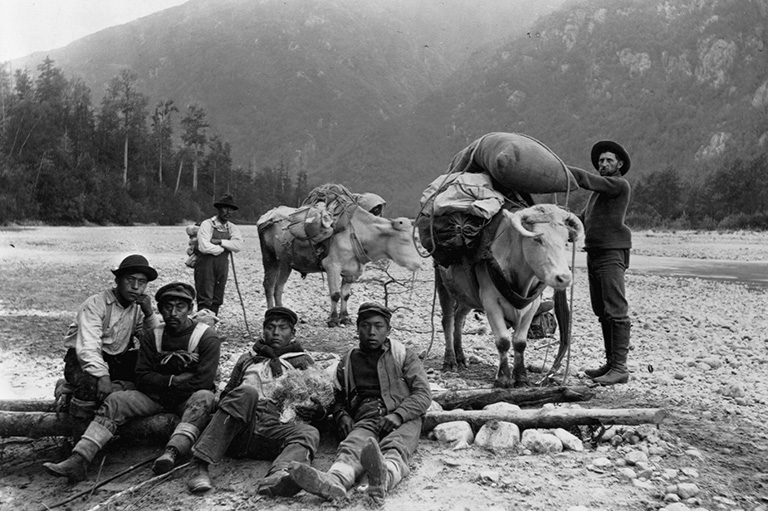

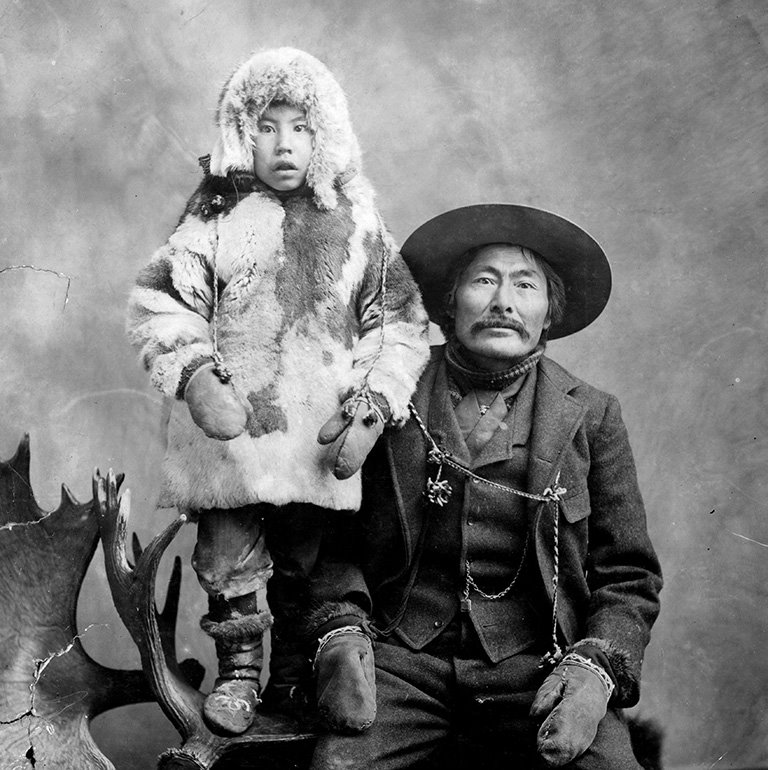

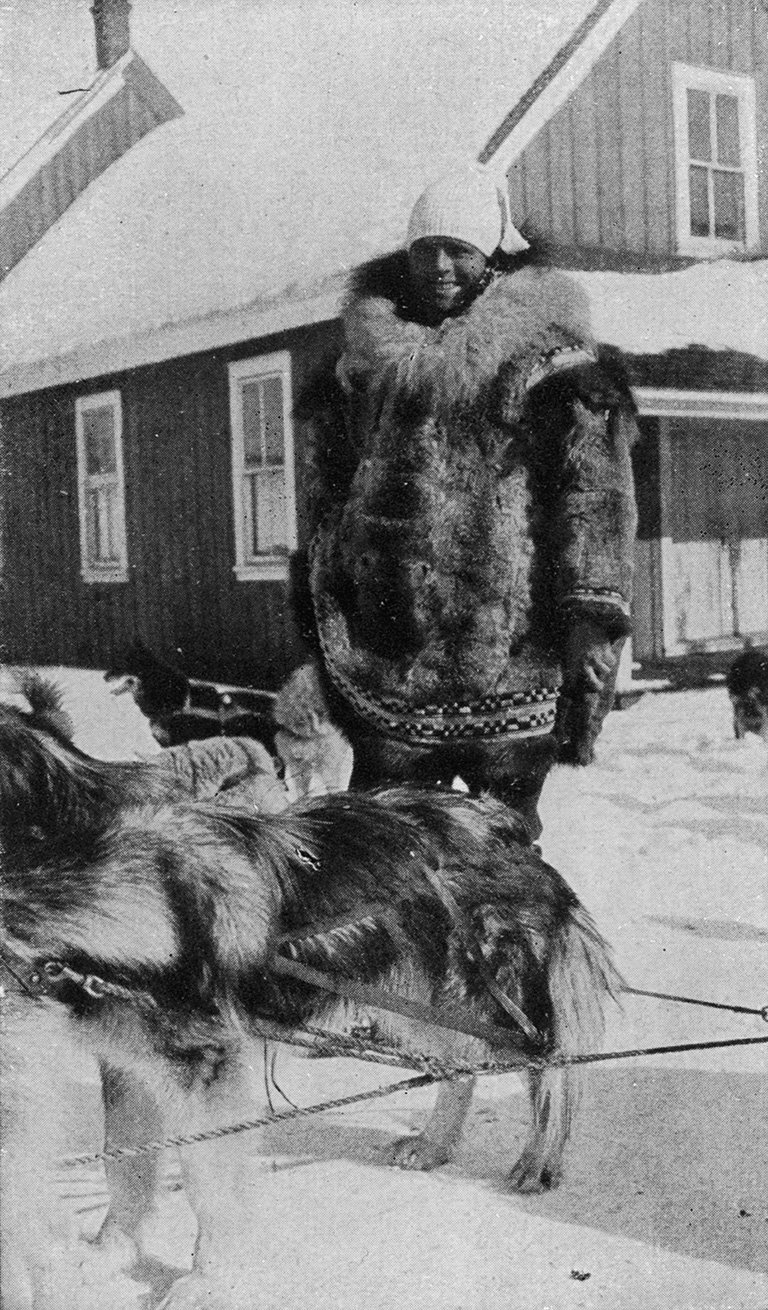

According to archaeologists, First Nations people have lived in the northern region now known as Yukon for at least fourteen thousand years. In the 1890s they were largely oblivious to the Dominion of Canada government in Ottawa and to the border with the United States. For the Tlingit, Hän Hwëch’in, Tr’ondëk, Kaska, Tagish, and Tutchone First Nations — whose combined population numbered about five thousand — this was their traditional territory, a homeland rich in resources including game, fish, and berries. European concepts of land ownership were meaningless to them; they belonged to the land, lived in harmony with its rhythms, and recognized the mutual dependence of all living creatures. These peoples played a significant yet overlooked role in the gold rush, as hunters, porters, and traders.

In contrast, the stampeders and their chroniclers, especially in the early years, chose to describe a treacherous, empty land — “several hundred thousand square miles of frigidity,” in the words of Jack London. Only their epic efforts, they implied, could wrest the precious yellow metal from the ground. They were largely indifferent, if not openly hostile, to the Indigenous population, and they were equally careless of the damage they were doing to Yukon’s ecology. Their mentality of conquest dominates popular accounts of the gold rush, and the gold rush dominates Yukon history. “It is a toxic mythology,” said Joseph Tisiga, a multidisciplinary artist from the Kaska Dene Nation, as the Kaska people are now called. “Anyone interested in the values of reconciliation, cultural healing, and a future of inclusion should ask to change the ‘gold rush’ identity of the Yukon.”

In 2005, when I began researching my book Gold Diggers, I looked for an individual who might voice the Indigenous experience. But I could not find the kind of written primary sources upon which I had been taught to rely: diaries, letters, and journals. Although I covered the story of the land’s Indigenous inhabitants extensively in my book, it remained in the background rather than the foreground.

It turns out that there were sources; I just didn’t know where to look. The first source was Indigenous oral histories, particularly those passed on by the Hän-speaking people known today as the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, whose traditional territory included what would become Dawson City. The second was the local newspapers of the time. From them I could have focused on the charismatic Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in leader Chief Isaac. If I had paid attention to these sources, I would not have repeated the mistakes of the colonial narrative, from which Yukon’s original peoples have been excluded.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

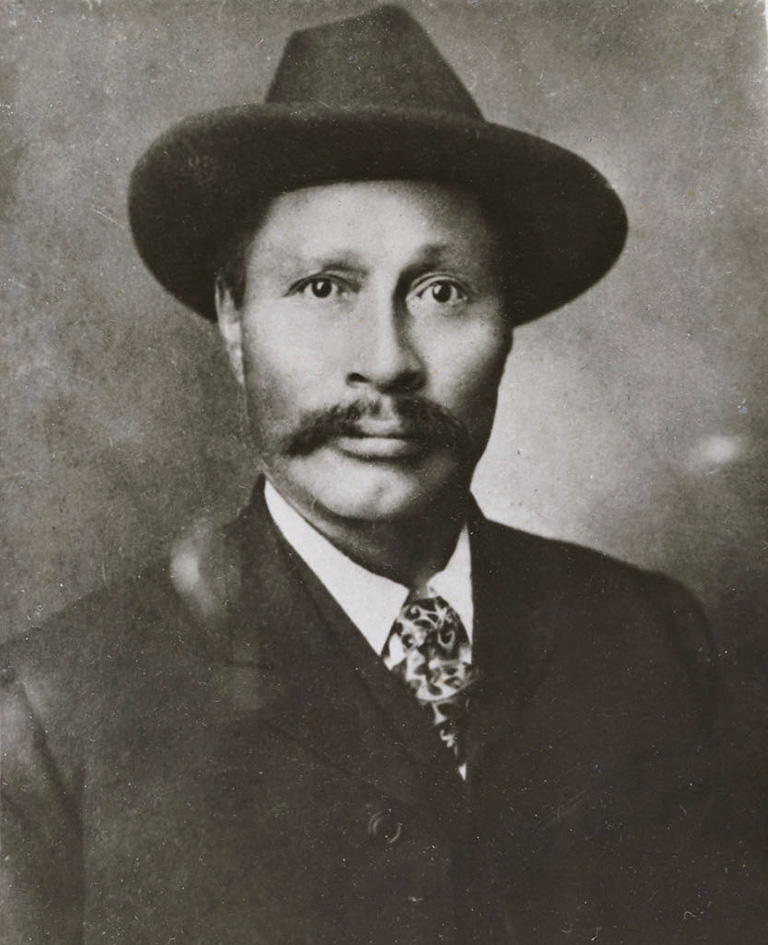

Photos of Chief Isaac, who became a Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in chief before the gold rush, show a tall, elegant man with high cheekbones and a friendly smile. His Indigenous name has been lost to history. The name “Isaac” was given to him by the Anglican Bishop William Bompas, and archival sources usually refer to him simply as “Chief Isaac.” An obituary in the Alaska Weekly of April 15, 1932, described him as “tall, slender, sinewy and muscular, he was of superior physical proportions and ... as well endowed mentally.”

In most photos, he wears a blend of Indigenous and Western dress — a heavily fringed and embroidered buckskin jacket and cloth pants. Born around 1847, he was married to a woman called Eliza Harper, and they had thirteen children, four of whom survived childhood — Fred, Charlie, Angela, and Patricia, known as “Princess Patricia” because she was the daughter of the chief. Chief Isaac’s granddaughter Joy Isaac recalls her mother telling her that Chief Isaac was “a good medicine man,” revered by his family and his people for his healing and hunting skills.

Joy Isaac and her relatives have recently created a website to commemorate Chief Isaac. There they describe how their ancestors were hunters and gatherers, connected to and dependent on their relationship with land, water, animals, and air. For centuries they moved with the seasons, spending each fall gathering berries, each winter hunting, and each summer fishing for salmon at the mud flat where a particular tributary rich in salmon flowed into the Yukon River.

Advertisement

Chief Isaac’s branch of the Hän Hwëch’in likely numbered about two hundred people. They called themselves “Tr’ondëk,” and this is why the prospectors gave the name Klondike — a corruption of Tr’ondëk — to the salmon-rich tributary flowing into the Yukon River. “Tr’o” refers to a special rock, a hammer rock, that they used to drive salmon-weir stakes into the tributary during their summer camp on the mud flat. “Ndëk” is a waterway or river. In time, the Tr’ondëk would add “Hwëch’in,” which means people, to their name — so “Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in” means People of the Hammer-rock River.

Long before the gold rush began, Chief Isaac was aware of the slow infiltration of Indigenous territories by southerners. For decades there was a robust and mutually beneficial trade in fox, bear, and lynx furs between Indigenous trappers and white traders. Missionaries had appeared in Indigenous villages. Chief Isaac himself had converted to Christianity (which he combined with traditional spiritual beliefs). Next came the miners, who travelled north from the thriving gold mines of California, Colorado, and British Columbia. They established a string of raucous mining camps along the Yukon River — Rampart City, Circle City, Eagle, Forty Mile, Fort Reliance, Sixty Mile, and Fort Selkirk.

Joy Isaac recalls her aunt Pat telling her that Chief Isaac “knew they were human beings, and he was friendly with them and welcomed them. And he told his people to be good to them, too.” There are stories of Indigenous hunters finding stranded and starving southerners and saving their lives. As Jackie Olson, the former executive director of the Klondike Visitors Association, who is herself Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, pointed out, “You see these old photos [from that period] labelled ‘Two Indian men,’ and it doesn’t even give their names. But you know the photographer probably wouldn’t even be there without their help.”

One of the first white people that Chief Isaac got to know was Jack McQuesten, a tall, burly American with a bushy moustache who worked for the Alaska Commercial Company and had established the Fort Reliance trading post on the banks of the Yukon River in 1874. McQuesten, whose wife, Kate, came from the Koyukon people of Alaska, learned a little Hän, the language of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people, and Chief Isaac learned a little English. The chief and the trader became friends.

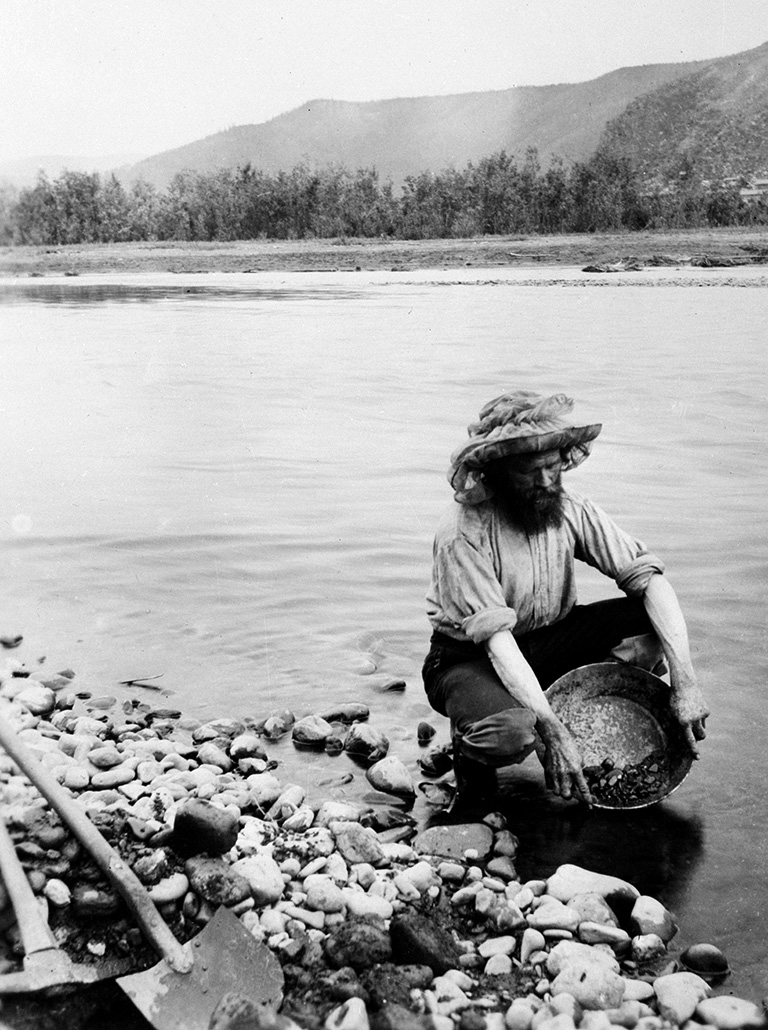

Small amounts of gold flakes and nuggets were enough to keep the gumbooted miners going, as they panned for alluvial gold along the Yukon and its tributaries. If any of them had stopped to chat with Chief Isaac as they floated down the Yukon River, they would have heard that a much bigger haul of soft yellow stones was available in the gravel at the mouth of the Klondike River. The chief’s granddaughter said that he knew there were “lots of big nuggets along the creeks.” But you can’t eat gold, so it had no value for people who lived on the land, and few prospectors bothered to communicate with the people who knew this land the best.

It was only when news leaked out of a spectacular strike on a Klondike creek in 1896 that the gold rush began. Who found the gold? For years, an American named George Carmack was credited with the strike, since the claim was registered in his name in the mining recorder’s office at Forty Mile. But Carmack was known as a lazy fellow, and even his contemporaries speculated that the gold was first sighted by his Tagish wife, Shaaw Tláa (also known as Kate Carmack), her brother Keish (whom Carmack called Skookum Jim), or Shaaw Tláa’s nephew Káa Goox (nicknamed Tagish Charlie). Carmack registered the claim because Indigenous claims were rarely honoured, and, anyway, prospectors preferred the version that named one of their own as the original finder. So Shaaw Tláa and her relatives have only walk-on parts in gold rush mythology.

Thousands of stampeders arrived at the mouth of the Klondike River in the spring of 1897, and Chief Isaac could see that there was going to be trouble. Aggressive newcomers didn’t confine themselves to Dawson City, the townsite on the opposite bank of the Klondike from Tr’ochëk, the traditional fishing settlement of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in. They spread into Tr’ochëk itself, staked all the available land, bought several of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in moosehide dwellings, and started building cabins. Soon Tr’ochëk was overwhelmed and the fishing equipment was vandalized. “My dad ... was afraid his people would learn bad habits from the white people, drinking and trouble like that,” Pat Isaac told her niece Joy. Chief Isaac decided that the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people should move.

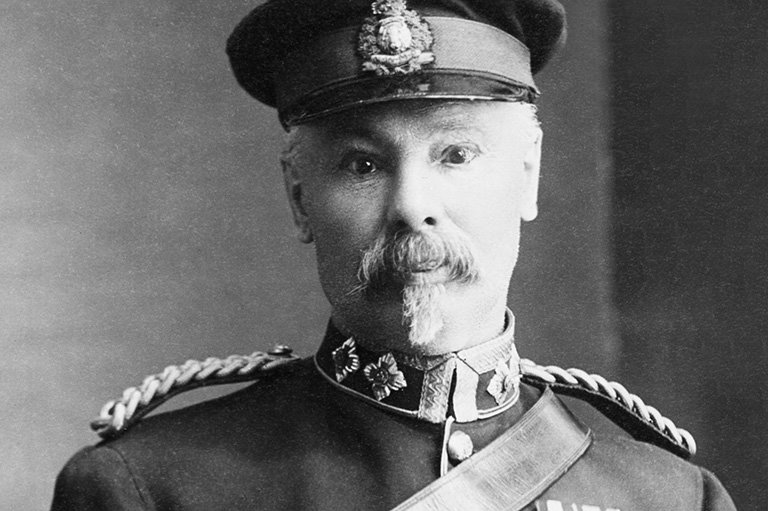

Chief Isaac was, in the words of the current Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Chief Roberta Joseph, “a remarkable leader. He had to adapt to new ways and ensure the safety of our people.” He conducted negotiations with the newcomers with a civility that was rarely reciprocated. His first request was that the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in should move to a plot of land on the Dawson side of the Klondike, but that was rudely rebuffed by the North West Mounted Police.

NWMP Inspector Charles Constantine had earmarked the area for his compound and made it clear that he didn’t want to share it with its original occupants.

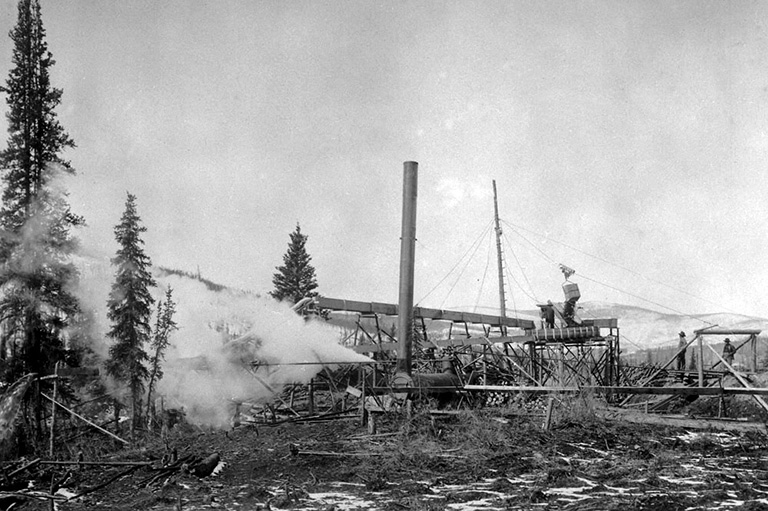

With hundreds more miners and their followers paddling down the Yukon River each day, a painful transition for the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in was inevitable. They struggled to learn English and to communicate with the newcomers, few of whom bothered to learn Hän. They watched the southerners overwhelm their fishing grounds, occupy Tr’ochëk, chop down forests for firewood, and rip apart the land around the creeks. By 1898, Dawson City had thirty thousand inhabitants and was the largest city west of Winnipeg and north of Seattle. What hope of survival did a few dozen Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in — vulnerable to the diseases that miners brought with them and to the temptation of whisky — have?

Yet Chief Isaac protected his people. He refused the dismissive suggestion from Constantine that Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in families should isolate themselves on islands in the middle of the Yukon River. Instead, he moved his people five kilometres downriver to a site called Moosehide Village.

There the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in continued living on the land for several decades, passing down their stories and celebrating their festivals. “He knew our Hän songs would be lost” in the turmoil, Chief Roberta Joseph told me, “so he asked our brothers and sisters in Alaska to keep them for us.” Alaska’s Tanana people returned the songs in the 1990s, a century after the gold rush. “We were at last able to hold our traditional potlaches again,” Joseph said.

The intruders had shouldered aside the land’s Indigenous residents and reduced them to near invisibility. If contemporary accounts of the great stampede mention them at all, it is often with disdain. Yet they were crucial to survival in Dawson. In the bitter winter of 1897–98, many Dawsonites would have starved had it not been for the moose meat supplied by skilled Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in hunters. During the peak years of the gold rush, Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in labourers worked on the Yukon paddlewheelers, the building sites, and, occasionally, the claims.

Chief Isaac was a frequent presence in Dawson City, speaking up for Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in who were accused of committing petty crimes or who were arrested for alleged drunkenness. By the end of the gold rush, his strength and diplomacy had won deep respect from Dawson officials. Dawson residents made him an honorary member of the Yukon Order of Pioneers and invited him to speak at Discovery Day, the annual celebration of the first gold strike on the Klondike. He was often photographed with dignitaries, including the Yukon commissioner and the Anglican bishop.

Chief Isaac was courteous to the newcomers, but he rejected their attitude toward his people and their territory. He used the three local newspapers — the Klondike Nugget, the Dawson Daily News, and the Yukon Sun — to convey important messages. He pointed out that the justice system was harsher to Indigenous offenders than to whites. He frequently reminded readers that non-Indigenous people had ruined the delicate ecological balance that had existed in the region before the gold rush. The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in had welcomed the miners, but in the process their own way of life had nearly been destroyed.

A newspaper clipping from the period preserves one of Chief Isaac’s passionate speeches, given in English, his second language: “Long time ago before the white man came along, Yukon Indian was happy. Indian had plenty game, no trouble and was fat. White man comes and Indian go out and kill meat to feed him. Indian gives white man clothes to wear and warm him by Indian fire. Byemby ... million white man come and cut down Indian’s wood, kill Indian’s game, take Indian’s gold out of the ground, give Indian nothing. Game all gone, wood all gone, Indian cold and hungry, white man no care.”

This was the voice that was missing in my 2010 book.

Today, the way mining has elbowed out the rest of Yukon history is under review. The latest example came in February 2021, when the fifty-seven-year-old Yukon Sourdough Rendezvous festival was rebranded as the Yukon Rendezvous festival. The word “sourdough,” slang for a white miner who had survived a Klondike winter, was dropped because of its colonial connotations, said representatives of the Yukon Sourdough Rendezvous Society, which organizes the event. (The society kept the word “sourdough” in its own name while removing it from the name of the festival.)

In response to the change, the society received an outpouring of “hate, bigotry, threats of vandalism and bullying,” the local CBC station reported. But some people defended the change. Lori Fox, a CBC columnist, pointed out that those who voiced outrage were defending a history that is “racist, sexist, misogynist and — quite frankly — a hot mess of highly questionable colonial behaviour.” The artist Joseph Tisiga added, “What and how a culture celebrates says a lot about its core values. Why was a festival created around someone who had spent only one year here? Come on! First Nations have spent thousands of years up here — living, not just ‘surviving.’ Yukon has promoted the gold rush as its central identity, but the cost of this identity is a legacy of First Nation displacement and exploitation.”

Tisiga pointed out that white superiority is “encoded into Yukon culture, with streets named after prospectors rather than our Elders.” During summers spent in Dawson City, he has often felt he is in a gold rush theme park. “The gold rush has been romanticized and it has obscured the peoples, art, and culture that have been here for thousands of years.”

Each summer, tourists arrive in Dawson City to pan for gold or to visit Diamond Tooth Gertie’s Gambling Hall and the Jack London Museum. Residents acknowledge the economic benefits of tourism. But now the visitors can hear the gold rush’s counter-narratives. Despite the damage done by the gold rush, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in have survived and, after a 1998 land agreement, prospered. Their government is now the largest employer in town. The Hän language is taught in the schools. Students — Indigenous and non-Indigenous — can take courses in hunting skills. And, since 2008, visitors have been invited into the stunning Dänojà Zho Cultural Centre to view a video about the community’s traditions, its role in the gold rush, and its economic and cultural survival and success. “There are other reasons to come here besides the gold rush,” said Olson, the former executive director of the Klondike Visitors Association. “For so long, our stories were so disturbing that they were swept under the carpet, and my generation was raised ‘white.’ But we are ready to tell our own stories, and all of a sudden people want to hear them.”

Wayne Potoroka, the mayor of Dawson City, added, “In Dawson we acknowledge that we all have a role to play in reconciliation. For too long we forgot the bad stuff that happened. The gold rush wasn’t all dancing girls. It was rough.”

Yet Chief Roberta Joseph argues that a larger story is still untold — the story of lost potential. “The gold rush meant a loss of opportunities for my ancestors. We could have been one of the most prosperous First Nations in Canada, but the wealth and culture of our traditional territory was reaped from under our feet.” Like Chief Isaac a century ago, she said, “we were left with nothing.”

THE MYTHMAKERS

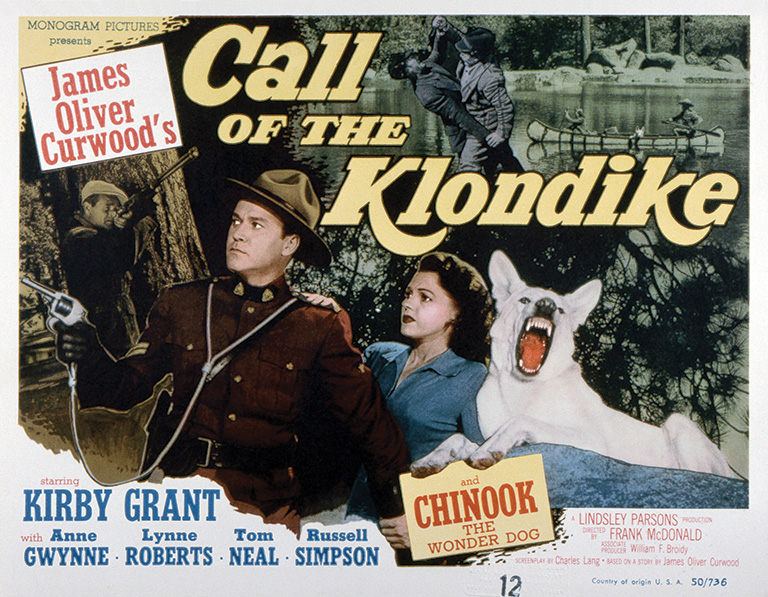

Writers, photographers, and filmmakers have mined the Yukon gold rush for creative inspiration. Whether true to life or wildly fantastic, their works have nearly always depicted the Klondike from the colonizers’ point of view.

Author Jack London wrote adventure stories inspired by his own experiences in the Klondike.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!