Life on the Land

In the late 1860s, the Dominion of Canada purchased Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company. The nearly eight million square kilometres of land extended over present-day parts of the prairies, northern Quebec, northern Ontario, and Nunavut.

For the architects of Canadian Confederation, the opportunity was too great to be missed. As George Brown, editor of Toronto’s Globe newspaper and a Father of Confederation, described it, Rupert’s Land was a “vast and fertile territory which is our birthright — and which no power on earth can prevent us occupying.”

Rupert’s Land was already home, though — to thousands of Inuit, First Nations, and Métis people who had lived in the area for much longer and, in some cases, since time immemorial. In areas close to the treeline, Indigenous groups including Innu, Dene, and Cree nations, along with some southern Inuit people, hunted, fished, and lived there already. Local histories of many Cree peoples mentioned the idea of being placed upon this land by the Creator, while Métis families, with a deeply ingrained sense of identity owing to a unique political and community history, drew their sense of nationhood from a distinctive past based in the area. In addition, further north, Inuit people adapted community life to the realities of the landscape, including technologies and methods for fishing, hunting, and gathering based on community needs.

For European settlers, the Indigenous peoples of Rupert’s Land and of the Northwest seemed to be homegrown exotics — the kind of “others” typically found across the ocean or on the other side of the world. In 1762, General James Murray, then governor of Quebec, characterized the Indigenous inhabitants of the lower north shore of the St. Lawrence River, whom he called “Esquimeaux,” or Eskimo, as “the wildest and most untamable of any.” If the Indigenous peoples of the area were mentioned at all, they were treated with colonizing contempt and as harbingers of a vanishing race. They were incidental to the “birthright” described by Brown — inconvenient obstacles to development whose cultures seemed so different from the ones Europeans knew.

The distance, both literal and figurative, of life in the North became an important theme for explorers, observers, and colonizers who entered the territory and, later, for photographers who followed. The cultures that outsiders encountered were filtered through a colonial gaze that sought to see everything, catalogue everything, and classify it all. It was a task for which photography was ideally suited. As colonial photographic practices flourished in the nineteenth century and extended into the twentieth, the Inuit, First Nations, and the Métis — the Indigenous peoples of the Northwest — were photographed at work, at play, and as targets of a growing colonial presence in the North.

As the “Magazine of the North,” as its subtitle indicated, colonial voyeurism was part and parcel of The Beaver’s business. Emphasizing the rugged landscapes and lifestyle of the peoples whose images photographers captured, the magazine’s treatment of northern people and northern life was often tainted with paternalistic and assimilationist overtones.

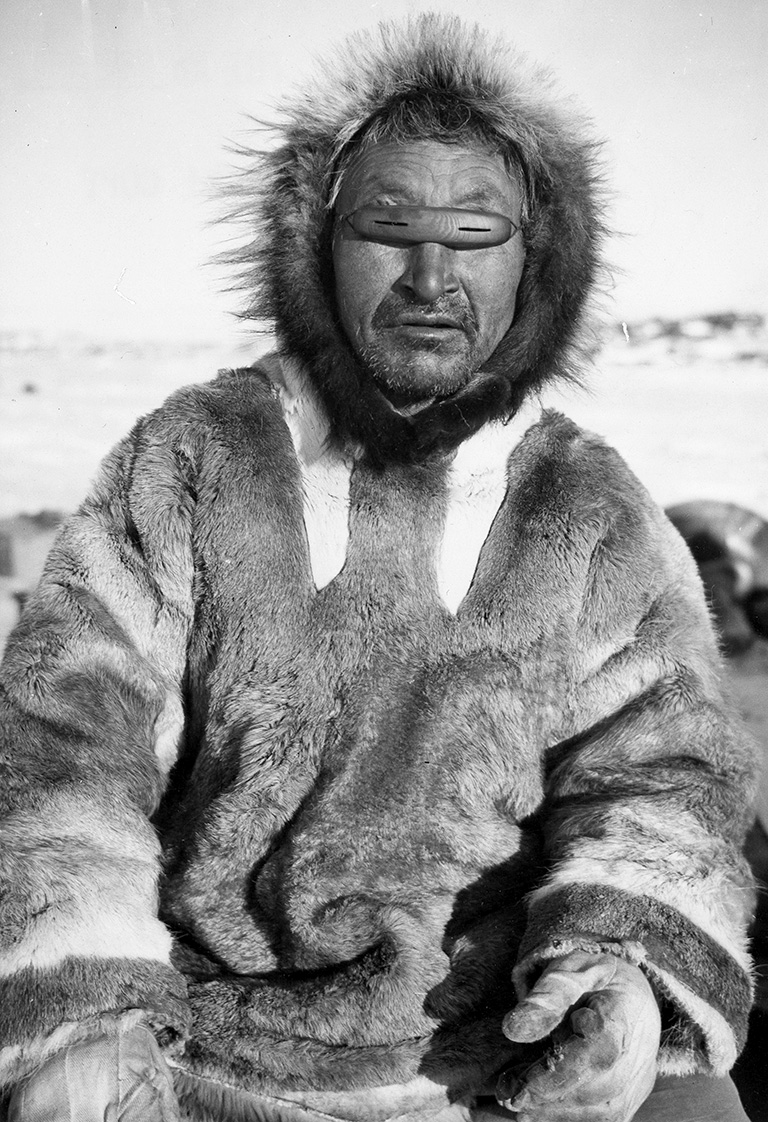

Henry Aod-la-toak wears a pair of wooden goggles that was used to prevent snow blindness. The undated photo is by Canon J.H. Webster, an Anglican missionary who ministered in Coppermine, N.W.T., from the 1930s to the 1950s. It appeared in the March 1949 issue in an article on life in the Coronation Gulf region of what’s now Nunavut.

Indigenous people featured in its pages were photographed in a way to make the images interesting to a non-Indigenous audience. The photography of Indigenous subjects as people who did not necessarily want to be photographed, or were made to pose for photographs that were not intended for them, was a most aggressive and intimate incursion into private and community life. As people would find out, these incursions also often had important practical consequences that came from letting in the outside world. In addition, photographs of Indigenous peoples were often published in The Beaver without proper names assigned to their subjects, emphasizing the perceived “wildness” of the people depicted.

In many cases, photography was a deliberate tool of propaganda. But photography is about two sides — the photographer and the subject of the photograph.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

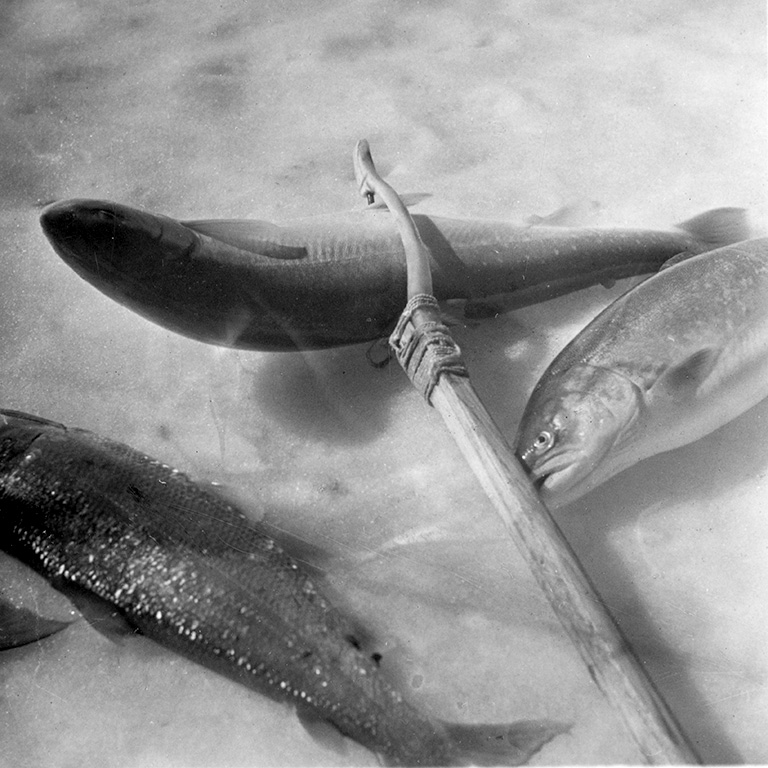

Fish speared by a pair of Inuit families fishing along the south shore of the Simpson Strait, in what’s now Nunavut, in 1942. HBC post manager L.A. Learmonth took this photo for a March 1942 story on fishing techniques in the North.

For those who were photographed, images of children playing and families working together demonstrated the strength and safety found in community, in kinship, and in good relationships. Multiple generations shown living side by side revealed the importance of Indigenous-centred intergenerational learning for First Nations, the Métis, and the Inuit. Adapted technologies made from materials gleaned from the land highlighted the ingenuity and industriousness of peoples who recognized its gifts and possibilities. As a whole, the photographs shown in The Beaver magazine can emphasize the importance of learning from Indigenous peoples and of understanding the relationships that made it possible for families, communities, and nations to survive.

Many of the photographs also reveal cultures in flux, confronted by important changes. As many Inuit people recall, the arrival of Qallunaat, or non-Inuit outsiders, in greater numbers throughout the nineteenth century was cause for alarm. The growing influence and infiltration of European ideas and technologies transformed life for the Inuit, though not always for the better. Greater centralization of communities in the mid-twentieth century also transformed Inuit social life, including social roles and responsibilities. Practically speaking, photos emphasizing the alleged ease of new technologies such as the rifle or the chainsaw, as compared to the old ways, and photographs demonstrating the transformations brought about by residential schools and a growing Royal Canadian Mounted Police presence, are ominous reminders of the dangers of misinterpreting cultures that were adapted to their environment and imposing outside solutions.

For First Nations in remote northern communities in this area, as well as Métis people living alongside communities or within them, the photographs also document important changes. The incursion of non-Indigenous people, including outsider technologies, diseases, ideas about social organization, and “civilization” more generally, increasingly threatened communities organized and preserved by rules for social order and survival forged in lived experience on the land.

In viewing the photographs today with a new lens, we are confronted by new perspectives on the people depicted in them. On one hand, the photography of Indigenous peoples by European photographers can be understood as an attempt to document and to categorize those “exotics” through a colonial gaze — one that sought to justify a growing presence in the area and an increasing interference in First Nations, Métis, and Inuit systems of governance and social order. But, on the other hand, these images also reveal a depth that would not have been understood by the photographers — one that underscores the brilliance, the joy, and the resilience of the Indigenous peoples of the Northwest.

What outcomes might we see today had European settlers chosen to value the technologies, the knowledge, and the understanding of the land demonstrated by the photographs in The Beaver? What sort of differences might reveal themselves had Europeans at the time recognized what they were truly seeing? Distinctive technologies, ways of governance, and systems of knowing may have been overlooked by outsiders who travelled there. But, for the people captured in photographs, evidence of strong and vibrant families, communities, and cultures persisting through hundreds and even thousands of years provide an alternative way of looking at the value of the photographs published by The Beaver.

A pair of Inuit girls, possibly Lucy and Agnes Oliktoak, play on a swing at Holman, now Ulukhaktok, N.W.T., in August 1961. The photograph is by Villy Svarre.

Joe Nasogaluak prepares to harpoon a beluga whale [circa 1936]. Photographer: Richard N. Hourde. Name provided by Darrel Nasogaluak. Knowledge provided by members of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation.

An Inuit woman identified as Louisa scrapes an ice window inside an igloo at Povungnetuk, in what’s now Nunavut, in a 1959 photo by Richard Harrington.

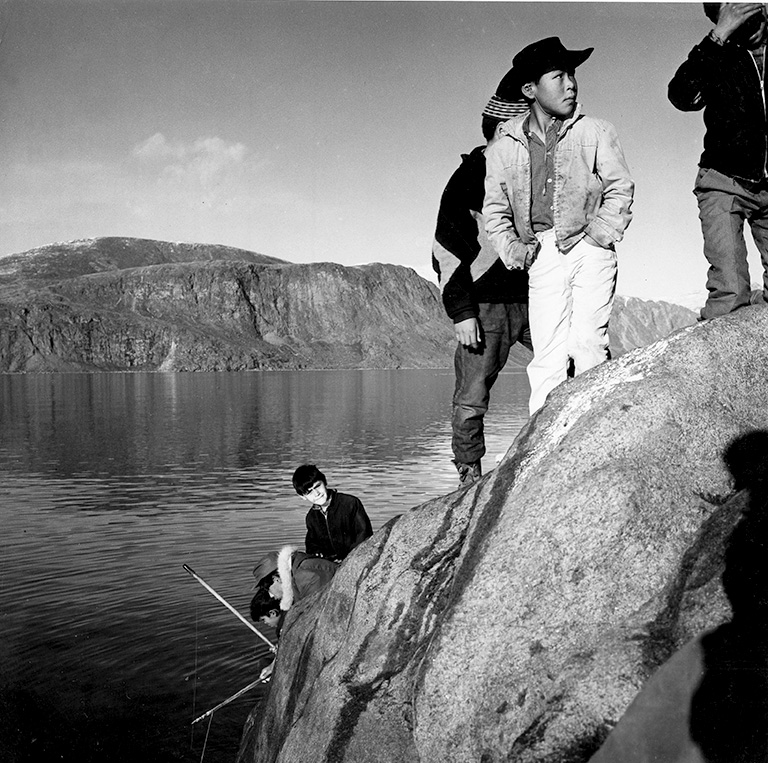

“Boys fishing for sculpins at Pangnirtung” 1966. [Lemoalei Arnaqaq (on top of rock with cowboy hat); Alen Kilebuk sitting. Lemoalei bought a cowboy hat because they were always playing Western movies.] Photographer: Fred Bruemmer. Names and knowledge in square brackets provided by a member of the Pangnirtung community.

Elizabeth Ningeok displays a basket woven from grass at Port Harrison, N.W.T., in this 1959 photo by Richard Harrington.

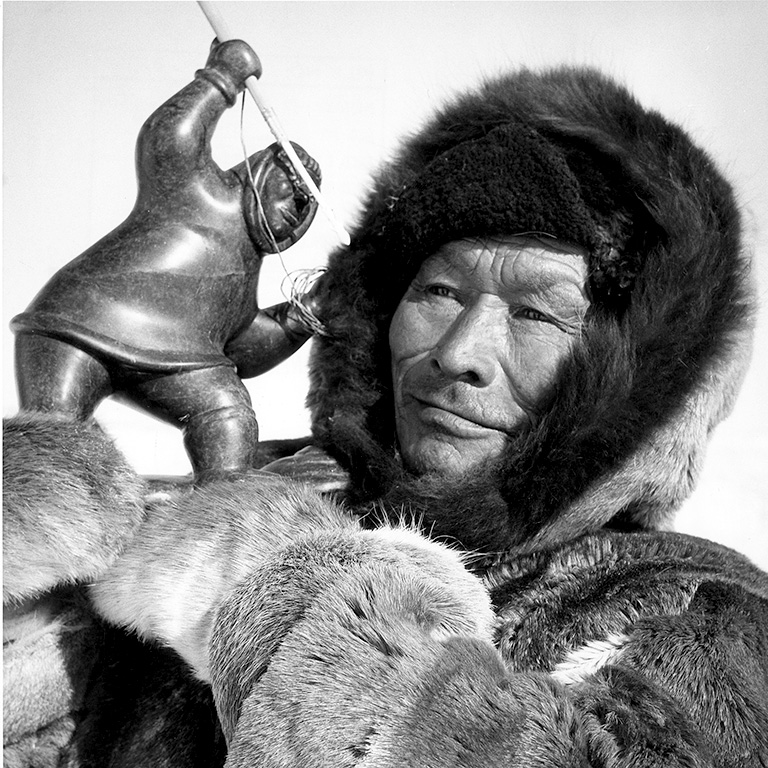

Ningiuk (Ningeyuk) Willia holds a carving by Lucassie Nowyakudluk in this 1959 photo taken by Richard Harrington at Port Harrison, N.W.T.

Choirboy John Vehus, a member of the Gwich’in peoples, lights altar candles at the Cathedral of All Saints at Aklavik, N.W.T., circa early 1950s. Behind him unfolds a northern-themed reimagining of the nativity scene, with Madonna and child dressed in ermine furs. Surrounding them are Inuit and Nascopie-Cree gift-bearers, as well as two men representing the RCMP and the HBC, respectively. An assortment of northern animals completes the scene. This photo by George Hunter appeared in the December 1953 issue with a story titled “Cathedral of the North.”

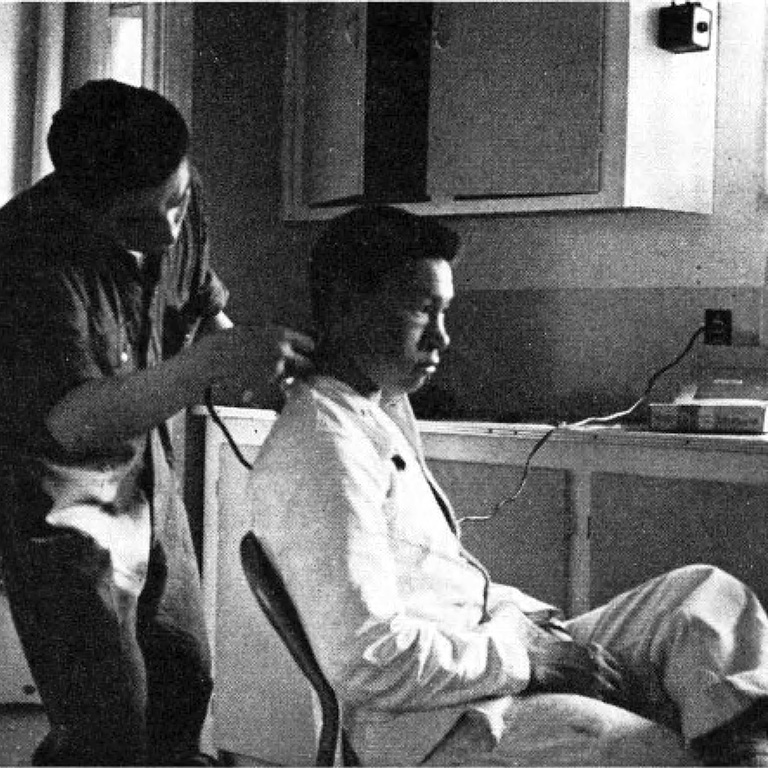

An unidentified Inuit barber gives a man a haircut in Frobisher Bay, in what’s now Nunavut, circa 1958–59. The photo appeared in the Summer 1962 issue with an article by American anthropologist Toshio Yatsushiro about the changing lives of Inuit people in Canada.

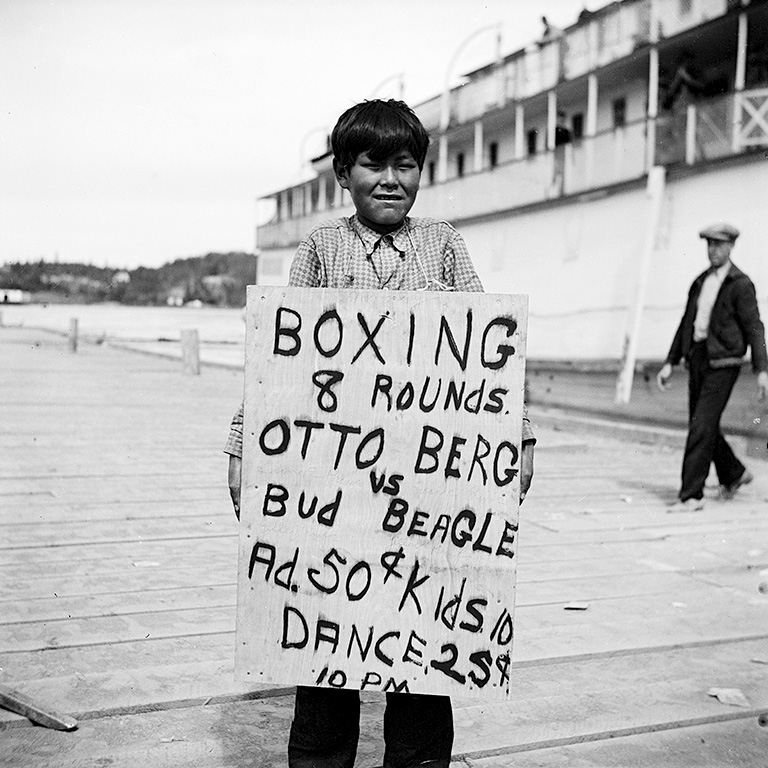

An unidentified boy advertises a boxing match and dance to visitors travelling aboard the SS Distributor in this 1936 photo by Richard N. Hourde. Owned by the HBC, the paddlewheeler plied the waters of the Northwest Territories’ Mackenzie River for around two decades.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement