Headwaters of Their Own Stream

Seven artists came together in the early 1970s to fight collectively for the inclusion of Indigenous art within the mainstream Canadian art world. These artists broke with identity definitions and boundaries imposed on First Nations people. They fought against double standards and exclusionary practices that treated the work of Indigenous artists as a type of handicraft, a categorization that prevented their work from being shown in mainstream galleries and museums.

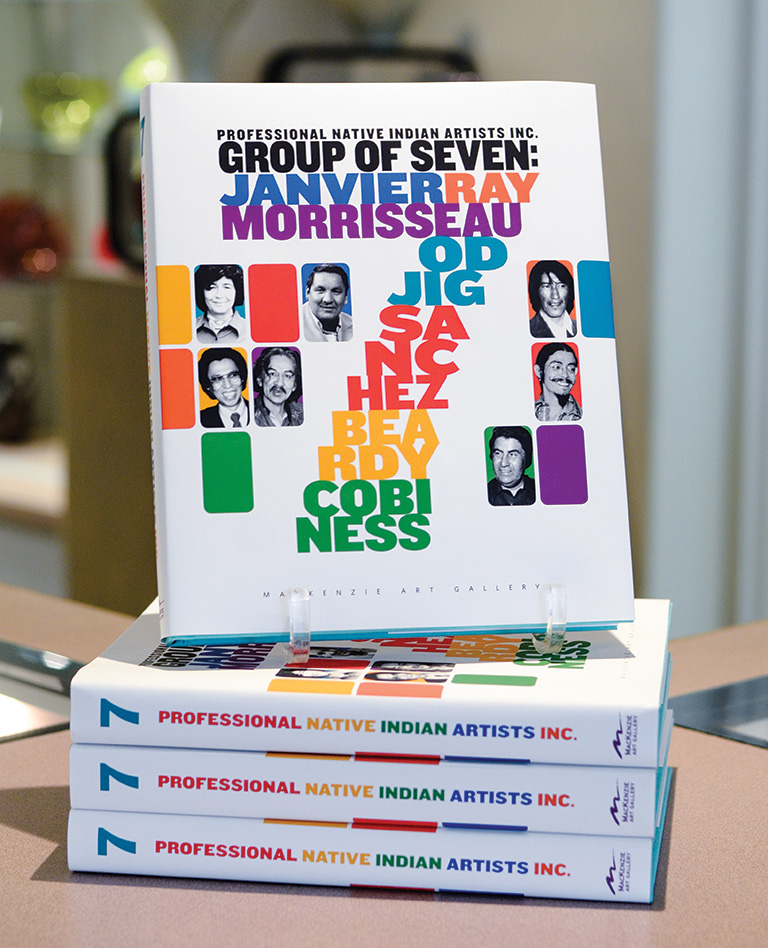

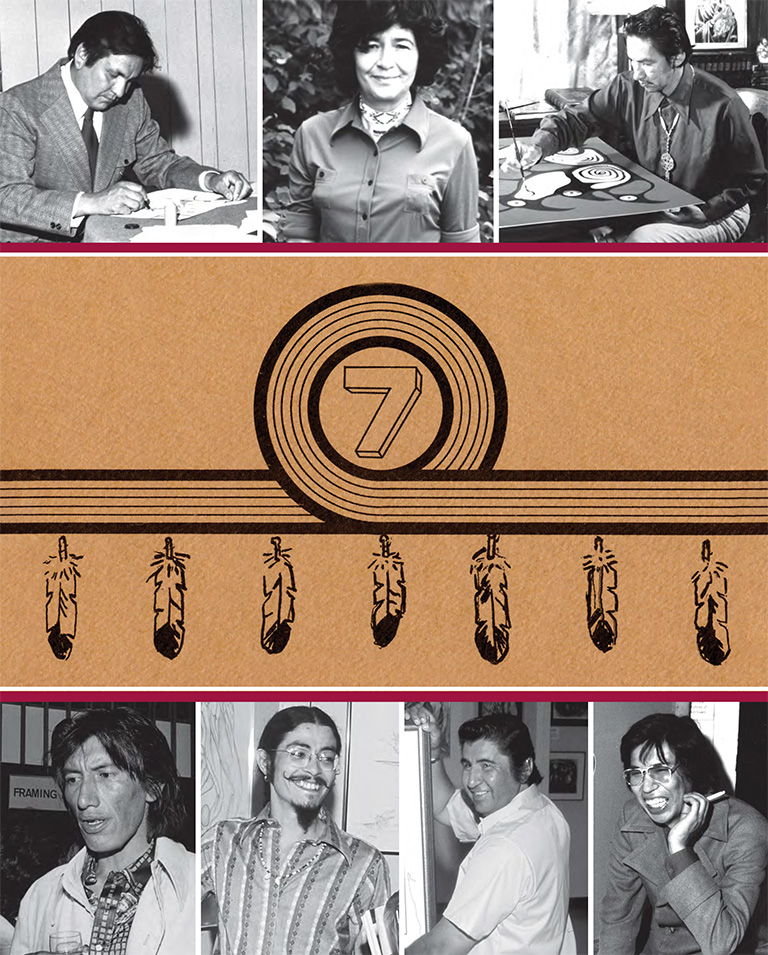

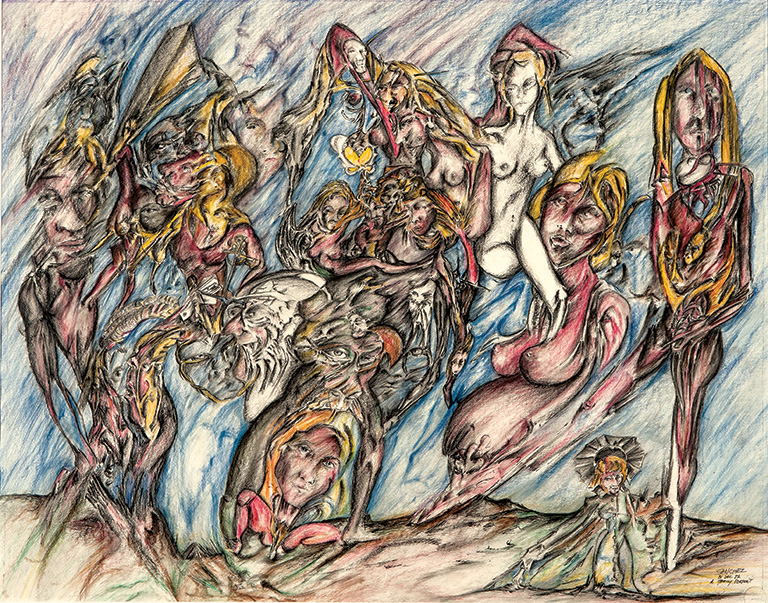

By the end of 1972, this “group of seven” — Jackson Beardy, Eddy Cobiness, Alex Janvier, Norval Morrisseau, Daphne Odjig, Carl Ray, and Joseph Sanchez — constituted the first self-organized, autonomous First Nations artists’ advocacy collective in Canada. Stimulating a new way of thinking about the lives and art of First Nations people, they signalled a new course for the exhibition and reception of contemporary Indigenous art.

My own interest in the group, formally incorporated as the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. (PNIAI), began many years ago and eventually culminated in a book project and a major exhibition in September 2013 during my time as curator at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina. I felt both obligated and empowered to make room for those who had been left out of the mainstream rt world, and to honour those who had come before me — artists whose commitment, efforts, and sacrifices had opened doors for me as an Indigenous curator, artist, and arts administrator and whose combined efforts were responsible in many ways for many of the positions I have held.

I had recently given birth to my daughter; around the gallery, the joke was that the exhibition had a second curator, because my daughter spent so much time in my arms or on my lap as we put the final touches on the installation and then while finalizing the publication of the book. The image of Alex Janvier holding my daughter and sharing his memories as we walked through the exhibition with his wife, Jacqueline Janvier, and fellow group member Joseph Sanchez is deeply etched in my mind. Intergenerational sharing was a central motivation for the exhibition and the book. My desire was to share the story of the group, a history that began before my birth, so that those yet to be born (or just born!) would know its history and understand its significance for generations to come.

As one of Canada’s most important artist alliances, the PNIAI made history by demanding that its members be recognized as professional contemporary artists.

Historically, mainstream social, political, and cultural practices have supported the exclusion, marginalization, and misappropriation of Indigenous art. The convergence of events that led to the formation of the PNIAI arose from a resurgence of Indigenous political activism and cultural revival in the late 1960s. Constantly belittled, Indigenous people were faced with two options — to accept an inferior position in society or to speak out and stand up against oppressive conditions and imposed definitions.

A cultural and political breakthrough came with Expo 67, an international exhibition in Montreal that became the highlight of Canada’s 1967 centennial celebrations. This event allowed Indigenous artists to assert their own cultural identity within Canadian nationalism. The forces of change cropping up in the gatherings were an early indication of what could be possible when artists with common experiences and interests came together and worked towards a common goal. Looking back, trailblazing curator Tom Hill, the first Indigenous art curator in Canada, explained to me that Expo 67 “brought a sense of power to the artists, [as it] enabled Indigenous artists from all over Canada to meet for the first time and discuss their shared difficulties and interests.” The event forged a sense of common purpose among the participating artists, organizers, and activists from across Canada and demonstrated how their art could be used to communicate their ideas. This ripple of activity was a sign of things to come, including the formation of the PNIAI.

Recent history and events remind us that there is an intimate connection between Indigenous art and politics. Understanding how forces within Canadian society controlled the lives of First Nations people is key to appreciating the barriers these artists faced. In the 1960s, colonial attitudes of racial superiority still prevailed: First Nations people continued to be subjected to systemic anti-Native racism, informal segregation, and various governmental assimilation policies. This was understood all too well by members of the PNIAI. Beyond trying to increase the market and respect for their work, these artists were engaged in a broader political struggle, as they were directly affected by many of the cultural conventions and political policies that relegated First Nations people to secondary status in Canadian society and strictly regulated all aspects of their lives.

The group’s life experiences were inextricably tied to the then-named Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND) and to the Indian Act, whose policies affect the daily lives of people living under its jurisdiction. While all the members of the PNIAI experienced the heavy hand of DIAND, one of Janvier’s accounts offers a particularly vivid example of the trials they faced.

His story begins on the Cold Lake reserve in Alberta, which he could not leave without the permission of a government “Indian agent.” As a regulatory regime, the permit system was used by agents to strictly monitor and control the affairs of First Nations people, and Janvier’s arts education in the late 1950s is directly tied to this history. In our conversations, he has often talked about the time period when he was obliged to carry a written permit on his person in order to leave the reserve. Permits, though, were not always approved. When he was accepted to the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, he was told by the agent: “I don’t think you can make it.... That’s too difficult for you.” Instead, the agent only permitted him to go as far as Calgary. Even then, Janvier stated, “A few times I was contested by policemen. Any ‘upright citizen’ or churchman could demand [to see the pass] because I was in the ‘wrong place.’ I’m downtown. I had to prove the right to be there and to go to art school.”

Despite being top of his class in Calgary, Janvier felt that “the world wasn’t ready for me.... It was a problem because I wasn’t supposed to be there.” He believed in what he was doing but felt pushed away. “I began to feel the strength of racism — the power that [tried to keep me] from getting across to the other side.... I earned the right to get across ... but the society I entered into was not ready for anything like that.”

The repressive social, political, and cultural contexts in Canada at that time provoked a strong resistance among artists and activists alike. There was an unyielding desire among Indigenous people to have their voices heard and to ensure a continuation of their cultural practices. The impact of this growing social and cultural movement is evident in the work of the PNIAI. Celebrations of culture and identity, as well as tools for education and renewal, the works of these master artists provide a glimpse of struggles overcome, gates broken open, and a legacy that has gone under-recognized. Their work is also a testament to the ongoing relevance and strength of Indigenous peoples, their ideologies, and their cultures.

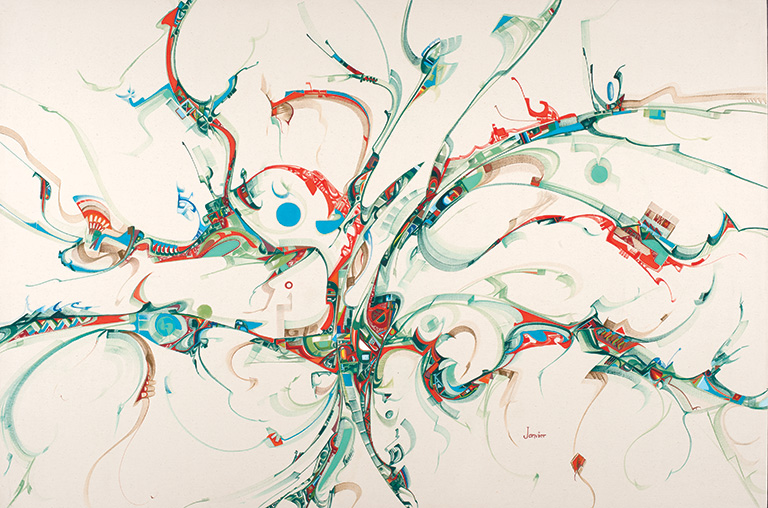

Though their personal aspirations were diverse, the members of the PNIAI became front-runners in the development of contemporary Indigenous art through the collective vision of the group. From their initial meetings in 1971 until their dissolution as a legal entity in 1979, the avant-gardism and stimulative newness of the images and styles these seven artists produced are significant. Their collective artistic impact, as well as their distinctive approaches and experimentation in expressing their experiences and cultures, remain a key source of inspiration for many. As a cultural and political entity, the PNIAI ignited a renaissance that gave subsequent Indigenous artists, arts advocacy organizations, and collectives energy and momentum that continue today. It is important, however, to acknowledge that in addition to the seven members of the PNIAI there were many artists producing work and contributing to a nationwide Indigenous reawakening. The decolonizing spirit that took hold through art as a first line of cultural and political defence is one that continues through to the present and has been described by art historian Carmen Robertson as a “Red Renaissance.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In the years following Expo 67, the PNIAI was among the first organizations to fight to establish a forum for the voices and perspectives of Indigenous artists; it was the first self-organized artists’ alliance to push for recognition of contemporary Indigenous art. However, the origins of this artists’ alliance grew out of grassroots efforts to meet the needs of Indigenous artists who had converged in one city — Winnipeg — in the late 1960s.

A common experience among members of the PNIAI, and for many other Indigenous artists, was the encounter with double standards. Artists were dismissed, told their work was either too “Native” or not “Native enough.” Signs of modernity in their work were rejected as incompatible or incongruent with society’s ingrained stereotypes of First Nations people and their art. In my conversations with her before her death in 2016, Daphne Odjig recalled once seeing a notice by an art gallery in a Winnipeg newspaper that said, “We accept all new artists.” Living further north at the time, she brought some work down to Winnipeg; however, the gallery owner, despite seeming enthused at first, was very cold with her. Odjig told me: “That’s when I decided: Well, they don’t want to take our work. I’m going to open up my own gallery. So, I opened my own shop. I said: They’ll have to come to me. I’ll never approach another gallery.” And she never did.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In 1970, Odjig and her husband, Chester Beavon, established Odjig Indian Prints of Canada Ltd. They opened a small craft store under the same name at 331 Donald Street in Winnipeg the following year. A few years later, they established the New Warehouse Gallery in the back of the store. “Odjig’s,” as it was commonly known, became a gathering place for artists who had been working in isolation from each other, not only in Winnipeg but as far afield as Ottawa and Toronto. Whether you were coming from the east or coming from the west, Odjig’s became the place to engage with other artists. The conversations generated at Odjig’s during that initial year led to the first tentative steps towards forming an organization. Janvier confirmed that it was a “vision that started under the tutelage of Daphne Odjig.” The connections between artists were further developed at informal gatherings in Winnipeg and eventually led to a concerted effort to form a unified professional group. Meetings usually took place at Daphne Odjig’s house, at the Northstar Inn in Winnipeg, or at Odjig’s, where artists shared their frustrations with the Canadian art establishment, grappled with prejudice, discussed aesthetics, and critiqued one another’s art.

Reminiscing about the early history of the group, Odjig recalled that she and Jackson Beardy “had many discussions [about forming a group] before it all started.” About six months after her shop opened, she got in touch with Eddy Cobiness through the National Indian Brotherhood, for which he had been producing illustrations and portraits. He would often stop by the gallery to discuss mutual concerns. In an effort to expand the discussions, a decision was made to contact other artists and to invite them to form a group. They contacted Norval Morrisseau through his art agent, and in the years to follow Odjig and her husband met with Carl Ray on a social basis a number of times. As for Alex Janvier, Odjig told me, “he was a bit of a biggie in Calgary. So that was a little intimidating for us. But after we met him, he said, ‘We’ll all meet down at your [craft shop]. We’ll meet together and make some plans.’” In her assessment, they came together out of a common need, “because they, too, felt a little isolated.”

At this stage they were a group of six. Several members recall that it was Ray who was the first to joke about becoming a group of seven, like the famous Canadian Group of Seven landscape painters of the 1920s and 1930s. The seventh member was, some might have said, an unlikely choice. Joseph Sanchez, a U.S. citizen of Pueblo, Spanish, and German descent, had served in the United States Marine Corps before moving to Canada in 1969. He first met Odjig in the fall of 1971, when he came into the store with a handful of drawings one day. A few weeks later, he dropped by during a meeting of the six artists. He was invited to join the group.

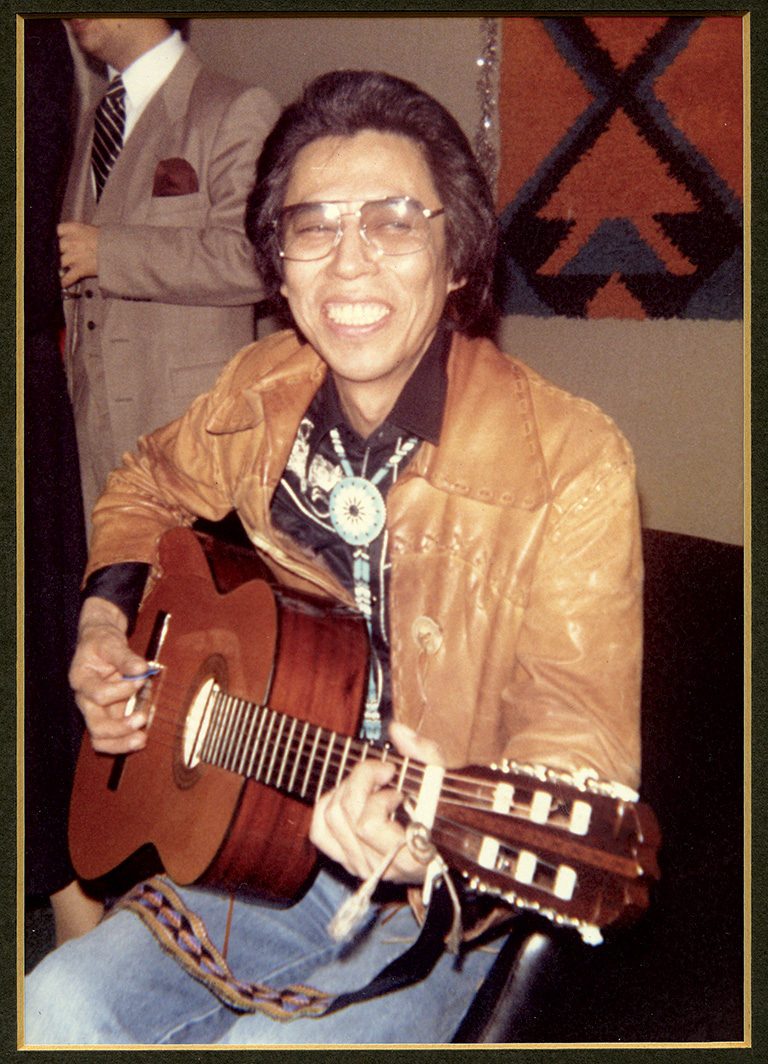

In one of my initial conversations with him, Sanchez recalled: “They welcomed me.... They could have said, well, he’s an American. He can’t be a part of this group. But that didn’t seem to matter to Daphne, or Alex, or Carl, or any of the group.” When I asked Alex Janvier about it, he reasoned that the Canada-U.S. border “was not set by us,” a sentiment shared by many Indigenous people. Despite spending the better part of an afternoon trying to come up with different ideas or concepts for a group name, the Group of Seven nickname stuck once the seventh member was invited to stay. Odjig concluded, “And that’s where it all started.... We didn’t even plan on it being seven, it just happened that way.”

Accounts vary, but what is clear is that by 1972 a group of seven had formed. By 1973, thoughts of incorporation had begun to circulate and to be debated among the members. Encouraged to legalize their status and formalize their association, they believed incorporation might enable them to secure funding to aid in the realization of the group’s objectives, particularly as they related to exhibitions, marketing, and education.

An application to officially incorporate as the Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporated was prepared in February 1974; however, the group was not legally incorporated until April 1, 1975.

There has been much informal debate as to whether the group was open to other artists at its inception or whether admittance was by invitation only. Certainly, there were many artists who came through Odjig’s gallery, or who exhibited with the members of the PNIAI in various venues, both during and after the group’s active life. These artists include, but are not limited to, Bill Reid, Roy Thomas, Clemence Wescoupe, Sam Ash, Josh Kakegamic, Don LaForte, Gerald Tailfeathers, Francis Kagige, Allen Sapp, and Benjamin Chee Chee. Some who might have had the opportunity to join, such as Bill Reid, were actively dissuaded by various external parties. Janvier met and worked with Reid during Expo 67 and again in the mid-1970s on the board of the National Indian Arts Council, an organization formed by the National Indian Arts and Crafts Corporation and funded by DIAND in an effort to mobilize the arts at the national level. Janvier often acknowledges Reid as an honorary member of the group, although he never formally joined it. According to Janvier, Reid was particularly helpful in dealing with the media.

The group’s struggle for mainstream acceptance was a constant battle that pitted the artists against government programs, a non-Indigenous public’s expectations, and government-supported institutions wanting art that reflected “Indianness” in style and content. More often than not, their work was relegated to commercial and ethno-galleries, cultural centres, museums, hallways, and offices, rather than being shown in the fine art galleries where they believed it belonged. In addition to the prevailing attitudes about First Nations art, it did not help that there were few to no employment opportunities for Indigenous curators who could engage in Indigenous ways of knowing and bridge world views in the presentation of Indigenous art.

Self-determination and self-definition were motivations at the heart of the group. The members were interested in the question of “Indian art” but defined it for themselves. Members were interested in expanding their horizons as artists, rather than succumbing to pre-packaged, narrow definitions and double standards around authenticity. In turn, they encouraged younger artists to create their own contemporary expressions as individuals. “Every artist paints from their own cultural heritage and their own experience,” Odjig asserted. “Whatever your heritage, it will come out in your brush. My counsel to young artists is to stop worrying about authenticity. It is within you.”

Seeking to control their creative processes, the members of the PNIAI did not allow others to determine the validity of their connections to their heritage. Each artist was encouraged to follow his or her own path. The practices of the senior members — Janvier, Morrisseau, Odjig, and Cobiness — that had begun in the 1950s and 1960s complemented those of the younger members, whose work also reflected non-Western inspirations. Although they had differing opinions, roles, priorities, and responsibilities, the members stood together. This unity gave them unprecedented strength and support, as Sanchez explained to me: “We understood the value of standing together as artists. I believe it was the power of Daphne, Norval, and Alex’s work that forced galleries and museums to accept the work of the other members. This was the strategy. The strength of the group allowed me to exhibit in places I could only dream of being included.”

The “you take one, you take all” motto described by Sanchez proved to be something that enabled the less-established members to gain ground. In speaking with Janvier, he recalled saying on occasion: “If the group doesn’t show, I don’t show.” Solidarity was all-important, as Janvier explained: “We weren’t taken too seriously by the media. And I think we were also slated to fail. We were given enough rope to hang ourselves. But they didn’t realize there were seven ropes, and so it was a longer hanging level,” he laughed. “So, there was some good luck that came our way by being ‘the group’ in that we weren’t hammered individually. It’s harder to hammer a group of people. You know, you’re a force. Your little army’s small, but you’re a little army.”

Interacting with others who shared similar experiences and cultural backgrounds was both stimulating and advantageous for the PNIAI members. The camaraderie and friendship that developed helped them to navigate territory that had been difficult to traverse on their own. Where one voice could sometimes be overlooked, the combined voices of several artists created a richly diverse and powerful statement. Working together gave them a strength and unity that caught the attention of the media and brought a contemporary image of First Nations art to the forefront.

In August 1972, curator Jacqueline Fry featured Beardy, Janvier, and Odjig in a three-person exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery entitled Treaty Numbers 23, 287, 1171: Three Indian Painters of the Prairies. It was the first exclusively contemporary First Nations art exhibition to be held in a public art gallery in Canada, and among the first exhibitions held in the gallery’s new building. This exhibition lent institutional credibility to their practice and gave a boost to their public profile that was soon reinforced. In June 1974 the Royal Ontario Museum hosted Canadian Indian Art ’74, which included all seven PNIAI artists. In our discussion about its development, exhibition curator Tom Hill recalled that “none of the major galleries were even looking seriously at First Nations art,” and he remembered encountering extreme ignorance and having to fight vigorously and defend the validity of an Indigenous exhibition. These two exhibitions were the first serious curatorial treatments of works by Indigenous artists as contemporary artists.

Following a year of organizational activity, in June 1974 the PNIAI announced plans for its first exhibition. An article in the Winnipeg Free Press featured a photograph of Cobiness presenting a drawing to Mayor Stephen Juba “as a centennial gift to Winnipeg from the Professional Native Indian Artists’ association.” In the months to come, Odjig expanded her Winnipeg print shop, establishing the New Warehouse Gallery in the back. Inaugural exhibition invitations were printed and dispersed, and an article in the Winnipeg Free Press reported on the December 8, 1974, opening, noting that “about 200 paintings, prints and drawings” featuring work by “‘a group of seven,’ an association of Indian artists” was on display. Although momentum was growing, the group was still seeking critical recognition as contemporary artists within the Canadian art establishment.

A major turning point came after Max Stern, an art dealer and the owner of the Dominion Gallery in Montreal, gave the group an exhibition. An advisor to the group, John Dennehy, had gone to Stern on the members’ behalf to pass on a message. As Janvier tells it, “I said: Tell the man that he brings art from all over the world. That he missed something in Canada. That he always brings something new from somewhere else, from outside.... Tell him that this time he’s going to bring something new from inside Canada.”

Max Stern scheduled his first exhibition of “Canadian Indian” art by the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. in the spring of 1975. Fierté sur toile: Tableaux par sept artistes indiens canadiens (usually translated as Colours of Pride: Paintings by Seven Professional Native Artists) opened March 11 at the Dominion Gallery. The PNIAI’s next exhibit, held in Ottawa in June 1975 at Wallack Galleries, was followed by another in October at the Art Emporium in Vancouver. These three exhibitions are often acknowledged as the last exhibitions by the PNIAI that featured solely the seven members. However, as late as 1987 members of the PNIAI, in varying configurations, continued to exhibit alongside other artists in several exhibitions, often in the context of, or with an affiliation noted to, the PNIAI name. Notable among these was Canadian Contemporary Native Arts: A Los Angeles Celebration, an exhibition curated by Tom Hill that ran from February 17 to April 26, 1987, at the Institute for the Study of the American West in Los Angeles.

THE ARTISTS

Jackson Beardy (1944–84) was born on the Garden Hill Reserve in the Island Lake region of Manitoba and was of Cree ancestry.

Eddy Cobiness (1933–96) was born in Warroad, Minnesota, and raised on Buffalo Point Reserve, Manitoba. He was Ojibway.

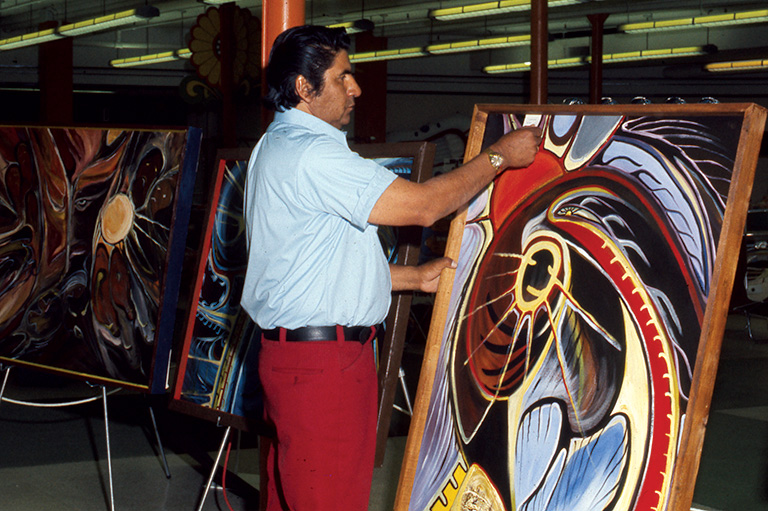

Alex Janvier (born 1935) was born at Cold Lake First Nations, Alberta, and is of Dene Suline and Saulteaux heritage.

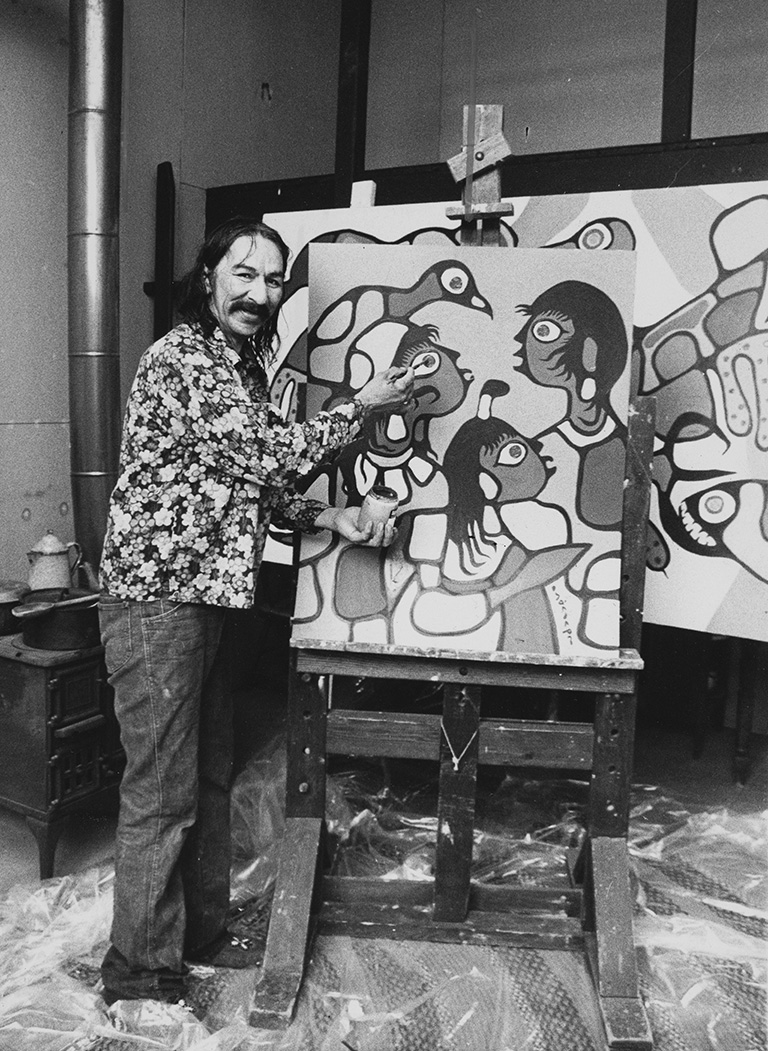

Norval Morrisseau (1932–2007) was raised on the Sand Point Reserve near Lake Nipigon, Ontario, and was of Ojibwa descent.

Daphne Odjig (1919-2016) was born on Wikwemikong on Manitoulin Island, Ontario, and was of Potawatomi and Odawa heritage.

Carl Ray (1943–78) was born on the Sandy Lake Reserve in Ontario and was of Cree heritage.

Joseph Sanchez (born 1948) was born in Trinidad, Colorado. He is an artist and curator of Spanish, German, and Pueblo descent.

In the end, despite their best efforts to remain a unified cohort, members found it too arduous to coordinate exhibitions and to raise funds without external support and additional expertise. The cohesiveness of the group was difficult to maintain as the artists began to work with different galleries and art dealers. Among the factors contributing to the group’s dissolution was Odjig’s decision to sell her shop and gallery and move to British Columbia in 1976. Without a central meeting point, the PNIAI members began to lose touch with one another as they became more involved with individual projects. Ray’s tragic death in September 1978 led to the further disintegration of the group. While there is no record of a surrender of the organization’s charter, according to Corporations Canada files the PNIAI corporation was officially dissolved on April 27, 1979.

Reflecting on the PNIAI’s part in history, in her essay “First Nations Activism Through the Arts” for the Banff Centre Press publication Questions of Community: Artists, Audiences, Coalitions, curator Lee-Ann Martin observed: “This group incorporated two of the most important features of organizations that would follow — providing support to individuals and lobbying for Indigenous artists as a whole.”

With an emphasis on professional accreditation and exhibiting and marketing their work, their interests and artistic aspirations were national and international in scope. Their intent was to cast a wide net and to mentor and support young Indigenous artists across Canada. As a result, Indigenous people began to recognize their art as a vital expression of an Indigeneity that embraces the notion that form and content are shaped by individual experience, which includes our shared colonial, North American, and European influences.

Curator Jacqueline Fry also recognized the significance of the complex position adopted by individual PNIAI members at an early point. In her 1972 exhibition publication she wrote that the works by these artists “are important, not only because they demonstrate the permanence of traditional [First Nations] culture but also because they reveal the presence of living, creative sources that, firmly rooted in the multi-cultured world of today, open the way to a more understanding world tomorrow.”

Building on the momentum of the PNIAI, the first National Conference on Aboriginal Art was held in 1978 on Manitoulin Island, Ontario, with Odjig and Janvier in attendance. Subsequent conferences followed across Canada in 1979 and 1983, resulting in the establishment of a national Native arts organization, the Society of Canadian Artists of Native Ancestry (SCANA) in 1985. Subsequent SCANA conferences followed in 1987 and 1993.

Reflecting on the PNIAI’s contribution to this history, artist Robert Houle noted: “They gave us a profile. I think for me, that’s what they established.... I had absolutely no idea what contemporary Native art was ... [but then] they came along.... And all of a sudden, you had something.... I think in many ways they probably started the ball rolling [towards] SCANA.” Continuing the dialogue initiated by the PNIAI, artists at these early SCANA meetings criticized the pervasive ethnological and anthropological views of contemporary Indigenous art and artists and confronted the exclusion of Indigenous arts within mainstream institutions including the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Vancouver Art Gallery, and the National Gallery of Canada. Recognizing the need for professional-development opportunities, they fought for increased access to these institutions for Indigenous curators whose cultural knowledge and experiences would transform Eurocentric theory and museum practices, enhance understanding, and contextualize contemporary Indigenous art from Indigenous perspectives.

While short-lived, the significance of the PNIAI in the history of Canadian art cannot be underestimated. The forward thinking of these pivotal artists has had an undeniable cultural and political impact. Even as PNIAI members focused on advancing their own careers as artists, they never lost sight of their larger political goal of raising the profile of Indigenous peoples. They functioned as part of a larger movement that challenged outdated racial stereotypes and forced a recognition of Indigenous artists as a vital part of Canada’s past, present, and future identity.

Reaching across cultural boundaries, their art caused excitement on the Canadian contemporary art scene. By fearlessly portraying the reality of Canada from a First Nations perspective, and by sharing the Indigenous world views and distinct aesthetics that permeate their work, they expanded the vocabulary of contemporary visual art and set a new standard for the artists who followed in their wake. Their story is a significant part of contemporary art history in Canada, one in which the foundation for a thriving professional Indigenous arts community was laid and the work of Indigenous artists and curators was subsequently propelled to national and international prominence today.

I have been a witness to the spirit that pours out of the artworks of the PNIAI members and into the hearts of so many. I am humbled and proud to have been in a position to honour this group and to share a glimpse of their story — a glimpse of a vision that flourished despite the struggles these artists faced within the context of mainstream Canadian society. The contributions of these artists to the history of First Nations aesthetic production and to the history of art on Turtle Island is of national importance. It is my hope that an intergenerational and cross-cultural audience will continue to benefit from learning about these artists’ and other Indigenous people’s experiences and histories.

The desire for self-determination and positive change that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s was a response to conditions that, sadly, are little altered today. After decades of denial regarding the deplorable experiences, conditions, and oppression faced by many Indigenous communities, intercultural relations continue to be informed by discriminatory beliefs and behaviours targeted at Indigenous cultures. This significantly affects the experiences of many individuals and communities, both personally and professionally.

However, as Indigenous and non-Indigenous people reside together in these territories, we are witnessing a new level of mindfulness. A deeper understanding of our shared and complex histories can help folks see connections to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis histories in their everyday lives. In turn, this informs our understanding and our actions and carries over into areas of our professional and private lives. We move forward by knowing where we come from and by making individual commitments to contribute to a more positive future for current and future generations, in whatever way we can.

A final thought from the insights of Alex Janvier, who shared these words with a full house while looking at the artworks by PNIAI members hanging together at the September 21, 2013, opening night of the 7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. exhibition at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina:

“What you see here is ... a true story, and that’s how it began, and ever since then we haven’t stopped. Members of this group, some of them have gone on to their graves, but you’ll see their work, they will talk to you with their art. Our story is really a Canadian story, a real Canadian story. It comes from here, by the people from here, and it’s about here. I welcome all of you to take a good look and be proud. I’ve travelled around the world quite a bit ... but when you come back to Canada, you almost want to kiss the earth that you come from because it’s so good to come home. This art here ... I hope will give you the same feeling, that every one of you has come home.”

ARTISTS AND ALLIES

As the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. sought recognition and inclusion by mainstream institutions through the late 1970s and 1980s, it was critical for the artists to work hand in hand with receptive non-Indigenous curators and other individuals who were in positions to assist this aim.

Jacqueline Fry, Elizabeth McLuhan, Audrey Hawthorn, Carol Phillips, and Carol Podedworny were among these early allies. Fortunately, there were also some individuals — private collectors, commercial dealers, and other artists — acting in tandem with the group, or on its behalf, who offered support to Indigenous artists in various capacities, including Herbert T. Schwarz, Robert Fox, John Kurtz, Helen E. Band, Bernhard Cinader, Phillip Gevik, Len Anthony, and Bill Lobchuk of Winnipeg’s Grand Western Canadian Screen Shop. Beginning to fight their way into the bastions of the Canadian contemporary art world, early Indigenous curatorial leaders included Tom Hill, Robert Houle, Gerald McMaster, Doreen Jensen, Lee-Ann Martin, Joane Cardinal-Schubert, Bob Boyer, Viviane Gray, and Gloria Cranmer; but they were often met with resistance and faced many challenges.

Ultimately, the careers of Indigenous artists were primarily in the hands of non-Indigenous people who did not necessarily have their best interests at heart. In the end, it was incumbent upon artists to show that they were serious professional artists and that they ought to be treated with the same respect given to other contemporary artists.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

The Editor's Circle was founded in 2020 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Canada’s History-The Beaver magazine. Gifts from patrons and supporters of $500 or more will be recognized annually.

You might also like...

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!