It's War. It's War. It's Russia

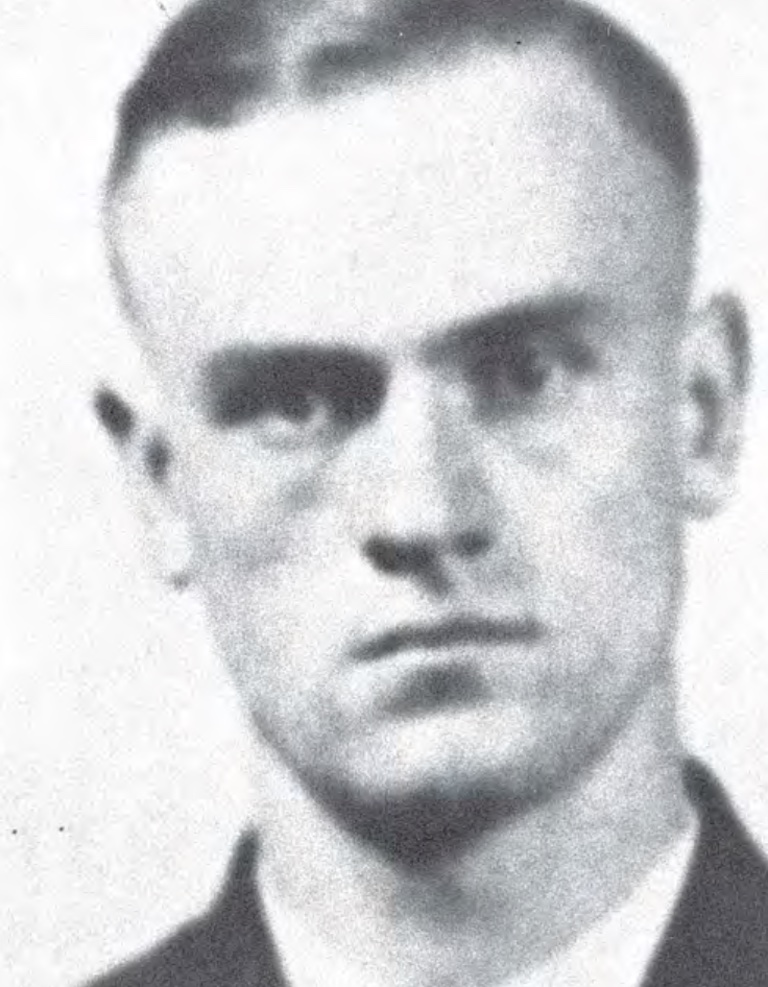

In the evening of September 5, 1945, Igor Gouzenko walked nervously through the lobby of the Soviet Emmbassy, with the unblinking gaze of Vladimir Lenin’s bust on his back. As he left his workplace for the last time, carrying more than one hundred incriminating documents, he knew he was not safe from the prying watch of Soviet eyes.

Gouzenko ambled along the streets of Ottawa, the weather balmy for a September evening, towards the offices of the Ottawa Journal. Only a month prior, the same streets had been bursting with gaiety to celebrate the surrender of Japan and the end of the Second World War. On this evening, though, the city was quiet, and Gouzenko walked alone, burdened by dozens of papers documenting a shocking secret — that Canada’s wartime ally, the Soviet Union, was engaged in a vast spying operation against the West.

Gouzenko was a cipher clerk in the employ of the Glavnoye Razvedyvatelnoye Upravlenie (GRU), the Soviet intelligence organization.

A man of humble Russian origins and modest height, Gouzenko had a sharp mind and an eye for detail; he was hand-picked by the Narodny Kommissariat Vnutrennikh Del (NKVD), the KGB’s predecessor, to train in military intelligence, in which he excelled. Gouzenko travelled to Canada in 1943 with Colonel Nikolai Zabotin, the Soviet military attaché, to cipher and deciper wartime secrets — not only those of the Axis powers but also items from the Allies.

Gouzenko excelled at the job, but, despite his proficiency, word came down in September 1944 that he and his family would be sent back to Moscow. The reasons for this are contested. Evelyn “Evy” Wilson, Gouzenko’s eldest daughter, told Canada’s History that it was a routine decision — that her father’s term of service in Canada had simply come to an end. However, some writers have claimed that Gouzenko was ordered to return to face punishment for unknown misdeeds. Either way, Zabotin, who was fond of Gouzenko, arranged for the cipher clerk to remain in Canada for another year.

Gouzenko’s motives for defecting are disputed. John Sawatsky, in his 1984 book Gouzenko: The Untold Story, attributes the decision largely to Gouzenko’s desire to escape the deprivation of Soviet society. However, Evy Wilson disagrees, believing that her parents’ “motivations for escaping were never selfish. How could it be if they did not expect to live? They even made plans for their son’s adoption in Canada. Their sole intent was to warn the West and to do so with documented proof.” Certainly, Gouzenko was disillusioned with Stalinism and yearned to raise his children in a nation free of oppression.

At 9:00 p.m. on September 5, Gouzenko entered the offices of the Ottawa Journal, stepped into the newsroom, and waited for acknowledgment from the staff. After receiving the attention of the night editor, Gouzenko was able to utter only a few words: “It’s war. It’s war. It’s Russia.” His heavy Russian accent made the incredible accusation even more difficult for the editor to comprehend. After all, the Soviet Union was an ally, still sharing in the postwar triumph.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

As Gouzenko grew increasingly agitated, the editor suggested that he share his accusations with the RCMP, whose offices were located within the Department of Justice on nearby Wellington Street.

Gouzenko rushed to the Justice Building, skipping the RCMP in favour of seeking the justice minister and future prime minister Louis St. Laurent. With the hours waning on Wednesday, and the minister not in, Gouzenko was told by departmental staff to return the following morning.

His first defection attempt foiled, a dejected and scared Gouzenko walked home to his wife, Svetlana, who was at the time pregnant with the couple’s second child. They had married as university sweethearts, both of them students at the esteemed Moscow Architectural Institute, before being transferred to Canada during the war. Having a noisy toddler proved fortuitous. The couple’s first apartment had shared paper-thin walls with the adjacent Zabotins, but Mrs. Zabotin reportedly detested the continual crying of their two-year-old, Andrei, and urged her husband to allow the Gouzenkos to move to another apartment building. This gave the Gouzenkos greater opportunity to plot their defection.

Distressed and fearful, the couple went to bed uncertain of their fate, aware that Soviet officials at the embassy would soon discover Igor’s treasonous act.

The following morning, September 6, Igor and Svetlana trekked back to the Justice Building, heavily laden with both Andrei and state secrets. Again they were denied, this time because St. Laurent refused to see them. The Gouzenkos then returned to the Ottawa Journal. With some effort, they were better able to communicate their story, but it was received with incredulity. Their story was either beyond belief or beyond the authority of the newspaper to report; in either case, the Ottawa Journal refused to print it. Once again, the couple was told to go to the RCMP. The Gouzenkos resisted the involvement of the police, but they agreed to visit the bureau of naturalization at the Crown attorney’s office.

Leaving Andrei with a neighbour, the couple attempted to apply for naturalization but were told that they didn’t meet the requirements. Approaching desperation, Igor asked the secretary to the Crown attorney, Fernande Coulson, for protection. Coulson called the RCMP on the Gouzenkos’ behalf, yet she received no aid. She then called the private secretary of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King — with the same result. Her frustrations mounting, Coulson was able to arrange a meeting between the Gouzenkos and an RCMP inspector for 9:30 a.m. the following morning.

But time was running out. The Gouzenkos — bone-tired and increasingly paranoid — were forced to return home, unprotected. They went to bed knowing that Soviet agents would soon be looking for them.

Holing themselves up in their apartment, the couple was startled by the sound of pounding on their front door. It was a member of the Soviet Embassy, who repeatedly called for Gouzenko to come out. From the apartment’s rear balcony, Gouzenko begged his neighbour, Harold Main, to shelter Andrei. Main, a Royal Canadian Air Force corporal, recognized the danger and hopped on his bicycle to bring the police himself. When the Soviet left, surely to return with more men, the Gouzenkos pleaded with their neighbour across the hall, Frances Elliott, who took in the desperate family. She, unlike so many, understood that this was a life-and-death situation.

All the while, the Gouzenkos’ fear grew. They had gambled and lost. Canadian officials did not seem to care, and any return to the embassy was a death sentence. From their window, they had seen two men peering back at them from a bench in Dundonald Park across the street. Igor ducked inside, worried that the men were spies. In fact they were RCMP officers monitoring the building.

Harold Main was able to convince the Ottawa city police to return with him, but they came with little enthusiasm. Meeting with the Gouzenkos, the officers explained that they were unable to do anything, as the apartment was considered Russian property. The police returned to the station, only to have to turn around once again.

From the keyhole of Elliott’s apartment, Igor watched as four members of the Soviet Embassy staff battered down his front door. They emptied drawers and searched the rooms, looking for some sign of their stolen documents or their missing cipher clerk. The returning police caught the intruders desperately scattering clothes and peering under the bed. The Soviets reluctantly left after giving their names and ranks to the police officers.

By morning, the Gouzenkos received their meeting with the RCMP, now with much greater urgency. At a cottage outside of Ottawa, officers debriefed Gouzenko and translated his documents. The files revealed a web of spies throughout the Western world, including a Canadian Member of Parliament, a British atomic scientist working with the Canadian Department of External Affairs in Montreal, and scientists and public servants throughout the United States and United Kingdom.

The shocking Gouzenko revelations became front-page news in papers around the world and would eventually fill the pages of dozens of books and countless academic journal articles.

They also inspired two Hollywood films. However, they are conspicuously absent in the public diaries of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King.

During the two months following the event, King kept another secret diary. This diary, now accessible through Library and Archives Canada, displays King’s disbelief in the alleged treachery.

He wrote: “The individual has incurred the displeasure of the embassy and is looking to shield himself.” Unfortunately, the evidence proved King wrong, and the Cold War was beginning — whether or not the prime minister was ready for it.

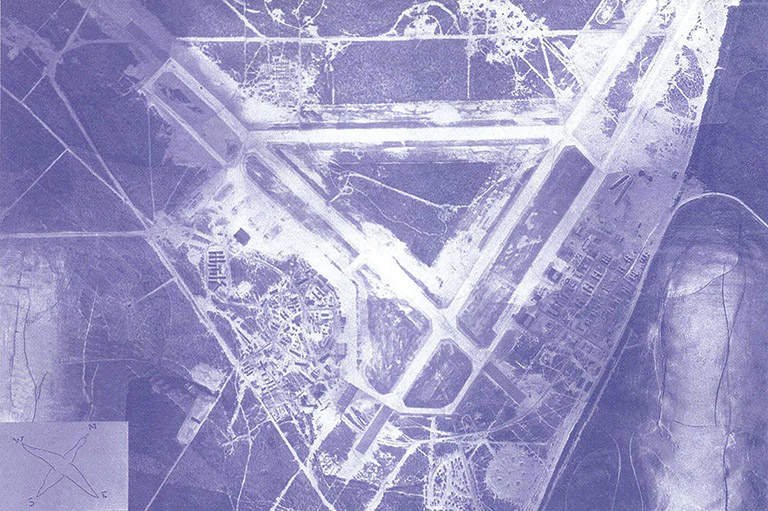

The Gouzenko family was relocated to Camp X, the Second World War spy-training camp near Oshawa, Ontario. There, under the surveillance of the RCMP, the Gouzenkos’ second child, Evelyn, was born. Their parents’ stories would be secret even to their children, with Andrei, Evy, and their younger siblings believing for nearly two decades that their parents were Czechoslovakian immigrants. Igor Gouzenko adopted an assumed name and wore a hood over his head during media interviews. He died of a heart attack in 1982, thirty-seven years after his defection. In 2001, Svetlana died and was buried next to her husband at Springcreek Cemetery in Mississauga, Ontario.

Andrew Kavchak, a former civil servant and amateur historian living in Ottawa, was surprised to find no monuments to the Gouzenkos in the city. “For years I wondered how was it possible that the location where Igor and Svetlana Gouzenko lived at the time of their defection was not marked by some sort of historic marker or plaque,” Kavchak said. “The first significant international incident of the Cold War happened in downtown Ottawa, and there was nothing to tell the public.”

In 1999, Kavchak began lobbying the federal and municipal governments to commemorate the Gouzenko affair. In 2002, after “many bumps and roadblocks along the way,” it received federal designation as an event of national historic significance, and it later received commemoration from the city of Ottawa. In 2004 a federal plaque honouring Gouzenko was placed in Ottawa’s Dundonald Park, opposite the apartment building where the family had lived.

The stories the Gouzenkos told presented as many surprises and uncertainties as the secrets they revealed, but the service they provided to the West is unquestionable. More than seventy-five years later, we continue to feel its impact.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!