Bombs in the Bush

On the night of November 10, 1950, a squadron of B-50 heavy bombers made its way from Goose Bay, Labrador, to its Strategic Air Command base in Arizona. As one aircraft approached the lower St. Lawrence River, near Rivière du Loup, about 160 kilometres downstream from Quebec City, first one and then a second of its four engines began to malfunction. Following standard emergency procedures, the crew jettisoned its load, then safely touched down at the nearest American base in Maine.

A cover story—that conventional bombs had been dumped in an emergency—was concocted, but the bomb was not conventional. It was a single 10,000-pound Mark IV atomic bomb, a variant of the Fat Boy atomic bomb that had destroyed Nagasaki five years earlier. The bomb did not contain its plutonium core, so there was no nuclear reaction, but the explosion 760 metres over the middle of the river shook residents on both shores of the St. Lawrence.

Article continues below...

-

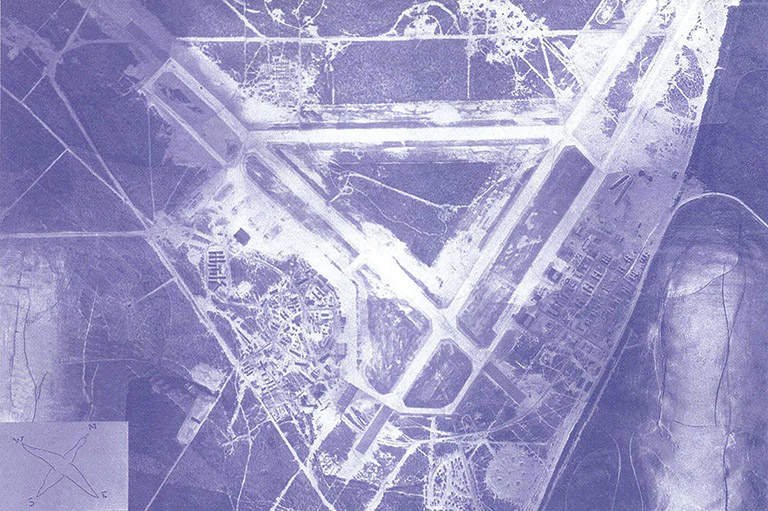

An aerial view of RCAF Station Goose Bay in 1942 showing the Canadian installations to the north and east and the smaller American presence to the south.Department of National Defence / RE75-1467

An aerial view of RCAF Station Goose Bay in 1942 showing the Canadian installations to the north and east and the smaller American presence to the south.Department of National Defence / RE75-1467 -

B-36 Peacemaker heavy bomber at Goose Air Base maintenance hangar, circa 1955.National Archives / 342-B-ND-010-17-156161AC

B-36 Peacemaker heavy bomber at Goose Air Base maintenance hangar, circa 1955.National Archives / 342-B-ND-010-17-156161AC -

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In August 1940, the two leaders signed the Ogdensburg Agreement, which created a joint board to oversee the defence of North America, implicitly including the British Crown Colony of Newfoundland. Though some Canadians accused King of placing Canadian defence in the control of the United States, the prime minister felt that military cooperation with the U.S. was essential and unavoidable.National Archives of Canada / C-16768

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In August 1940, the two leaders signed the Ogdensburg Agreement, which created a joint board to oversee the defence of North America, implicitly including the British Crown Colony of Newfoundland. Though some Canadians accused King of placing Canadian defence in the control of the United States, the prime minister felt that military cooperation with the U.S. was essential and unavoidable.National Archives of Canada / C-16768 -

Secretary of State for External Affairs Lester B. Pearson (left) with Minister of National Defence Brooke Claxton, September 1950. They were among the few close to Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent who knew the nature of the cargo the Americans were deploying to Goose Bay.National Archives of Canada / PA-121698

Secretary of State for External Affairs Lester B. Pearson (left) with Minister of National Defence Brooke Claxton, September 1950. They were among the few close to Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent who knew the nature of the cargo the Americans were deploying to Goose Bay.National Archives of Canada / PA-121698

They would not learn the true nature of the noise for almost half a century. Had they known that for the previous four months the bomb they heard, and fourteen others that made it safely back to American soil, had been stored under guard in the Labrador bush near Goose Air Base,1 they would have been even more startled.

But in 1950, knowledge that Goose Bay was home to what today are popularly called “weapons of mass destruction” was well guarded. It was one of the worst periods of the Cold War. In June, North Korean forces attacked southward, routing their adversaries and instilling a new sense of urgency in the development of plans for North American defence.

There was even some concern that the war was in part a ruse, designed to draw Free World forces to the Far East while the Soviets struck westward into Europe. One American response was to prepare to deploy its nuclear arsenal to possible danger zones. Goose Air Base, which was to see the first deployment of nuclear weapons on Canadian soil, was one of them—though few knew at the time.

Near the mouth of the Churchill River in Labrador, Goose Bay had been chosen ten years earlier to be the site of a new military airbase to serve Allied needs in the Second World War. In spring 1940, Germany's military successes in Europe, culminating in the collapse of France and the withdrawal of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk, led in North America to a growing concern for the survival of Britain and the possibility of a victorious Nazi Germany controlling the eastern Atlantic.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Ogdensburg Agreement in August 1940, which pledged joint Canadian-American defense of North America, implicitly including the British Crown Colony of Newfoundland. The next month, Britain, in exchange for desperately needed American warships, granted leases to the Americans for military bases in its Caribbean colonies as well as in Newfoundland: at Gander, Stephenville (Harmon Field), and Argentia.

With the war effort growing, however, bottlenecks at Gander soon led to American pressure for another North American air terminal. Goose Bay, leased from Newfoundland by Canada, was the result. At the end of 1942, there were five thousand American, Canadian, and British military and over three thousand construction workers on the base at Goose Bay. At its height, it was one of the busiest airports in the world. An estimated 24,000 aircraft, all bound for the United Kingdom, passed through the airport, and some quarter-million American troops returned through it at war’s end.

Postwar, Goose Bay should have declined into irrelevance. But the Soviet Union, the West’s ally in the Second World War, had quickly become its new enemy, and Goose Bay, being closer to Soviet targets for long-range nuclear bombers than any location in the continental United States, retained its strategic position.

The continued stationing of U.S. forces at Goose Bay was one of the topics of the first meeting between Mackenzie King and President Harry Truman in October 1946. In 1947, Canada, still leasing Goose Bay from Newfoundland, established a Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) training centre and opened a passenger terminal for civil aviation.

The Berlin Blockade of 19482 underlined the usefulness of Goose Bay as a supply route to Europe, while the explosion of a Soviet atom bomb the following year fed North American fears that the Soviets were developing the capability to launch an airborne atomic attack with little or no warning. (The international complexities of maintaining a two-nation military base at Goose Bay lessened somewhat with the admission of Newfoundland as Canada’s tenth province in 1949.)

Advertisement

When the Korean War broke out, the American Strategic Air Command (SAC), created in 1946 to coordinate strategic, long-range air combat, including nuclear bombers, approached Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent for permission to deploy eleven “special weapons”—the current American euphemism for atomic bombs—to Goose Bay for an experimental six-week period (which later turned into twelve). Secretary of State for External Affairs Lester B. Pearson was also privy to the discussions. Minister of National Defence Brooke Claxton raised in Cabinet the issue of SAC aircraft being deployed to Goose Bay, but made no mention of their special cargo. His recommendation was approved with little discussion.

Ten years later, a furor would break out over the issue of permitting nuclear weapons on Canadian soil. In 1957, the new Conservative government of John Diefenbaker had agreed to deploy in Canada American Bomarc-B missiles, which flowed from the creation that year between Canada and the U.S. of the North American Air Defence Agreement (NORAD) to combine and coordinate continental defensive efforts.

The government, however, sensing a growing antinuclear sentiment in Canada, waffled on the issue of arming the Bomarcs with nuclear payloads, eventually claiming that negotiations were ongoing with the United States to arm the missiles in the event of a crisis.

In 1963 the American government, exasperated by Diefenbaker’s indecision, coldly repudiated his claims and created an uproar in Canada that precipitated the fall of his minority government and its replacement by a Liberal government under Lester Pearson that vowed to honour earlier commitments.

But in 1950, political leaders were already sensitive to the issue, and it is not surprising that the St. Laurent government handled the Goose Bay deployment with the utmost caution and secrecy. That the deployment happened at all is testament to the fear that the Cold War had engendered in North American leaders.

Several years later, in reviewing a discussion with American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles on the use of tactical atomic weapons by NATO in Europe, Lester Pearson wrote of Dulles’s concern “that any such arrangements should be kept very secret.” Pearson agreed because he felt “it was practically impossible to reconcile constitutional positions with practical necessities of this kind.”

Perhaps St. Laurent and Pearson felt that, given the sensitivity of the issue, and the perceived Soviet threat, Canadians simply did not need to know. It had been, after all, only four years earlier that defecting Soviet intelligence officer Igor Gouzenko had tipped Canadian authorities to the presence of Soviet spy networks in Canada. However paternalistic St. Laurent and Pearson’s actions may appear now, in the atmosphere of the Cold War, where nuclear war seemed imminent, their positive and speedy response to the American request was prudent.

In late August 1950, three SAC B-50 squadrons of forty-three aircraft, with eleven “special weapons” assemblies, arrived at Goose Bay. At the time America’s nuclear arsenal was under the jurisdiction of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and the weapons themselves were stored at three national stockpile sites.

The plutonium cores for these weapons remained at the AEC sites, but could be deployed to forward bases, such as Goose Bay, within hours. American atomic weapons protocol required that nuclear weapons be removed from aircraft for local storage. Because Goose Air Base had but rudimentary facilities left over from the war, the bombs were stored about six kilometres off base in the Labrador bush where they were protected by an around-the-clock armed guard.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

At the height of this deployment over four thousand officers and men were stationed at “the Goose,” living mostly in tents. In November the weapons were returned to their national stockpile storage site at the Atomic Energy Commission’s Killeen Base in Texas. It was during this last transfer that a B-50 developed mechanical problems and dumped its weapon load in the St. Lawrence.

The number and type of nuclear weapons stored at Goose Air Base over the years is not known; diplomatic protocols for the stationing, storage, and deployment of “defensive” nuclear weapons were not completed until 1965. Only for a sixteen-month period in 1965 and 1966 did both Canadian and American governments acknowledge that defensive nuclear weapons were stored on the base.

However, the very use of Goose Bay by Strategic Air Command bombers, tankers, and interceptors implies that such defensive munitions and SAC strategic “special weapons” were present and stored in the secure munitions bunkers at Goose Bay Air Base on temporary deployments long before 1965.

In those postwar years, Goose Bay became a major component of the SAC defence network as Soviet-American hostility escalated. In 1953 the Soviet Union exploded a thermonuclear weapon, the hydrogen bomb, adding yet more urgency to North American defence plans.

The United States, which had concluded a new lease agreement with Canada in 1952 for 2,800 hectares at Goose Bay, began an extensive infrastructure program on the site, building sixty-two structures in the first year, including barracks, mess, hangars, administration buildings, and bunkers for the anticipated “special weapons” that Goose Air Base was designed to hold.

Over the next five years, as it was completed, Strategic Air Command KC-97 Stratotanker refueling aircraft were stationed at Goose Air Base to service the developing fleet of SAC medium and heavy nuclear bombers.

The latter included the B-36 Peacemaker heavy bomber and the B-47 Stratojet supersonic medium bomber. These aircraft were, with the aid of in-flight refueling by KC-97 Stratotankers at forward bases such as Goose, capable of striking a devastating blow at the industrial and demographic heart of the Soviet Union.

Coupled with the presence of aerial tankers at Goose Air Base were the jet interceptor aircraft of the Fifty-Ninth Fighter Interceptor Squadron deployed to protect the base and its facilities from attacks by Soviet long-range bombers. By 1955 American plans for Goose Air Base consisted of the deployment there, on ninety-day rotations, of tankers, heavy bombers, and jet interceptors that were equipped with nuclear air-to-air missiles.

In the event of a nuclear war, SAC plans called for American interceptors to protect Goose Bay against a Soviet nuclear bomber attack while American bombers headed north from their continental bases to attack Soviet targets, refueling along the way at bases such as Goose and those in Greenland.

With the launch of their Sputnik satellite in 1957, the Soviet Union revealed its emerging capacity to direct nuclear-laden intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) against North American military and industrial targets. By the late 1950s, American defence plans were evolving to rely less upon manned jet interceptors to destroy attacking Soviet bombers, and more upon the doctrine of massive retaliation against a full-scale missile attack.

Goose Air Base became a key component in a NATO network of bases and radar sites, serving both as a refueling and jet interceptor base for a retaliatory nuclear strike, and as the site of one of the links in the Pine-tree radar early warning system that stretched across Canada to aid surveillance of the North American airspace.

Goose Air Base lease ended in 1966, a reflection of changing defensive patterns and needs. Manned bombers were no longer the main threat from the Soviets nor were they the main weapon in the West. Redesignated CFB Goose Bay, the facility has since been used by NATO forces for low-level flight training. Some former Goose Air Base buildings are now used for commercial storage or leased to local businesses. And the former nuclear weapons bunkers? Today they’re used for storage.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!