Death of a Liberator, 1838

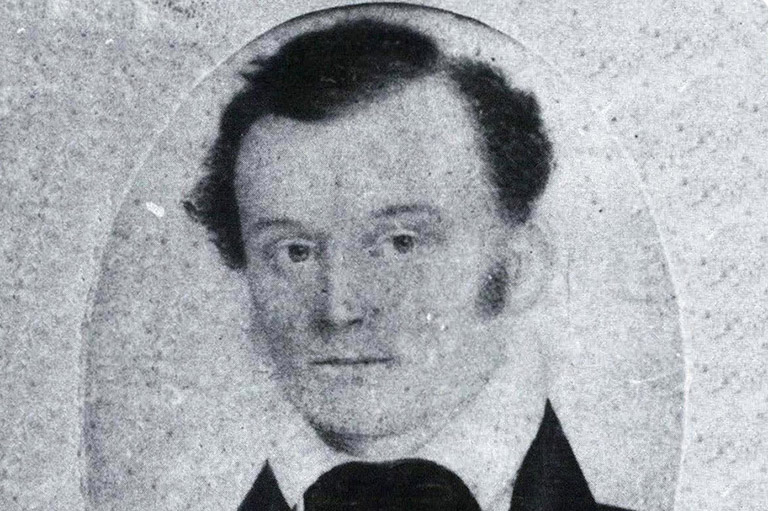

During the early morning of 12 November 1838, Nils Gustaf von Schoultz crossed into Upper Canada at the head of a 190-man American invasion force. His objectives were liberty, the expulsion of British “tyranny” from North America, and the establishment of a domestic republican form of government for Canadians.

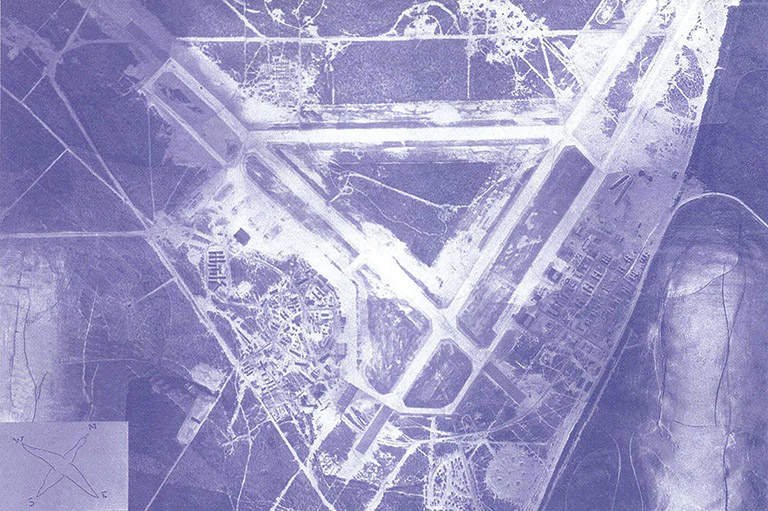

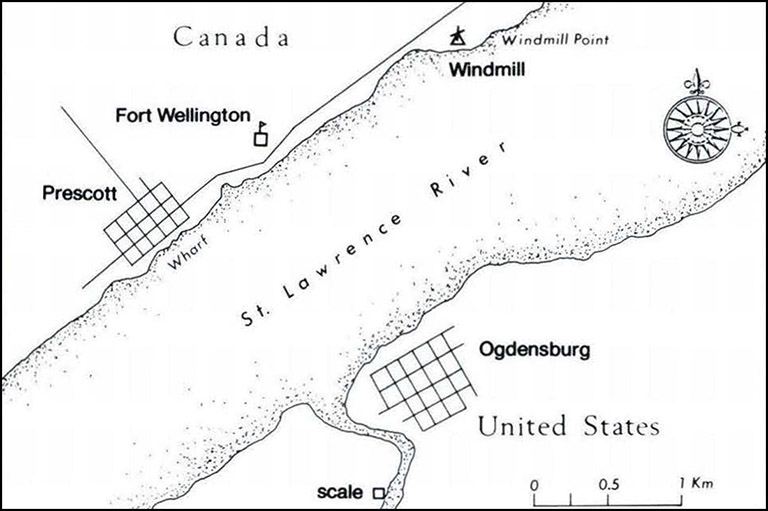

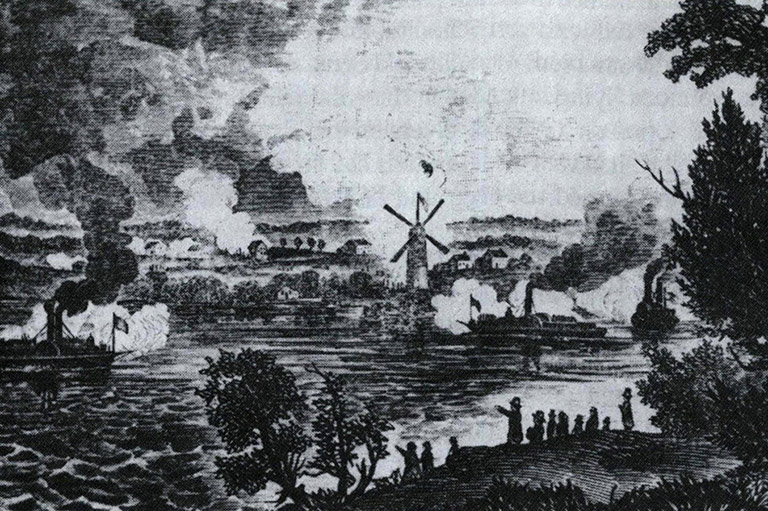

Their landing at a place called Windmill Point, located two kilometres east of the community of Prescott on the upper St. Lawrence River, was to be the launching of a “bloodless liberation” of Upper Canada sponsored by an American group called the Hunters’ Society of Onondaga County, New York. In the ensuing five days of fighting between Americans and Canadians, 37 men died and 89 were wounded. This attempted American invasion was an episode in the rebellions of 1837-38.

Less than one month later on 8 December Nils von Schoultz was hanged and buried at Fort Henry in Kingston. Like others before him and since, von Schoultz came to learn that Canadians are different from their American neighbours. On the night before his execution, in a final letter to a friend, he wrote:

Let no further blood be shed; and believe me, from what I have seen, that all the stories that were told about the sufferings of the Canadian people were untrue.

Nils von Schoultz was a tragic figure whose brief appearance on the stage of Canadian history helped shape the development of this emerging nation. In the days between his capture and execution, he also came to have a significant impact on the political development of a future Canadian prime minister.

Nils Gustaf von Schoultz was born on 7 October 1807 in Kuopio, Finland, the second son of a circuit court judge. In 1808, during the Napoleonic wars, Russian troops crossed the Finnish frontier and his family fled to Sweden.

After the Treaty of Fredrikshamn in 1808 many officials and refugees returned to Finland, but von Schoultz’s parents chose to remain in Sweden.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In 1821, the young Nils von Schoultz qualified for the Royal Military Academy in Stockholm where an older brother was already following a military career. By December 1823, von Schoultz was promoted to second lieutenant in the Svea Regiment of Artillery. In November 1830, he received an honourable discharge from the military.

In early 1831 stories from Poland reached Sweden that told of czarist repression and of fierce resistance by students and cadets in Warsaw. Many Swedes decided to assist the Poles against their Russian masters. One of these was von Schoultz who left for Poland in secrecy in 1831 and plunged headlong into the defence of Warsaw.

Von Schoultz later made his way to France where he joined the Foreign Legion in North Africa, moving on, in March of 1833, to join his family in Florence where his sister was studying music.

A year later he married Ann Cordelia Campbell in the English church at Florence. His wife was a member of a well-established Scottish merchant family from Edinburgh. The couple settled in Karlskrona, Sweden, where both their daughters were born.

Von Schoultz tried to settle down to a normal family life as a businessman-inventor but does not seem to have been successful. In June 1836, he visited London on business. His family remained in Sweden. A month later, without telling anyone, he left for the United States.

While he officially gave his nationality as Swedish, von Schoultz began passing himself off as a Pole. He was known to everyone as a former officer in the Polish Army who had been forced to leave his homeland by Russian oppressors.

Von Schoultz became interested in the salt industry developing around the upstate New York towns of Syracuse and Salina (Salina later merged to become part of Syracuse). He came to have many friends in Salina, which was located near the Canadian border.

Advertisement

In December 1837 authorities in Upper Canada put down an attempted rebellion. Many of the leaders of this uprising fled to the United States where they found sympathetic support for their proposals to liberate Canada from the oppression of British colonial rule.

Throughout 1838, a number of forces operating out of the United States conducted a series of raids and acts of piracy along the Canadian border. Newspapers, local government officials and merchants in the border states led the campaign to “liberate” Canada. Officials in Washington, under the administration of President Martin van Buren, however, were more cautious, so these liberation enthusiasts had to operate under the cloak of secrecy.

One organization that sprang to life in 1838 was the Patriot Hunters which formed hundreds of “Hunters’ Lodges” throughout the border states, recruited some 40,000 members and raised tens of thousands of dollars for the purchase of arms.

The Hunters’ Lodge of Salina recruited von Schoultz to their cause. Von Schoultz, for his part, eagerly accepted the role of liberating Canada from what he believed to be the oppression of Britain.

One of the leading Hunters in New York state, John Ward Birge, devised a plan to capture the British garrison of Fort Wellington located in Prescott. Directly opposite Prescott was Ogdensburg, New York, which was a hotbed of Hunter sympathizers. Birge believed that the seizing of Fort Wellington, one of the main British garrisons along the Canadian-American border, would prompt dissatisfied Canadians to rise up in revolt.

Birge began recruiting a force of some 300 men, arms and ammunition, cannon, and vessels for this attack. One of those he recruited was the recently arrived Nils von Schoultz.

Through the summer and fall of 1838, the Government of Upper Canada heard reports from informants living in the United States regarding the growth of popular American sentiment in favour of invading Canada and of the buildup of men, money and weapons in American communities along the border. The government began to re-build Fort Wellington, and to establish a number of militia units in communities near the American border.

During the night of Sunday, 11 November an American steamer towing two schooners entered Canadian waters. The private invasion force assembled by Birge—who had given himself the grandiose military title of “Major-General”—was aboard these vessels.

Near Prescott, the lines to the two schooners were cut. An attempt at a surprise docking at the wharf in Prescott was sighted by residents who raised the alarm. The two schooners retreated into the waters of the river and then separated.

At this point, the invasion of Canada by the Hunters became a combination of organizational chaos and low farce. The larger of the two schooners grounded on a sandbar in American waters. The smaller one, which had von Schoultz on board, landed on the Canadian side of the river at Windmill Point and began unloading its men and equipment.

Low farce occurred when “Major-General” Birge suddenly developed what he claimed was a stomach disorder and abruptly retired from the scene. Others also decided to remain in Ogdensburg. More than one hundred insurgents never made it to the Canadian side.

Later that Monday, officials of the United States Navy arrived in Ogdensburg and prevented any more attempts by American vessels to cross. By Tuesday, there was little communication between Ogdensburg and Windmill Point.

When the insurgents at Windmill Point realized that Birge would not be joining them, von Schoultz was chosen as commander.

The American insurgents might have been more successful despite their appalling lack of preparation. While the landing at Windmill Point was totally unplanned, the insurgents were fortunate to find a massive stone windmill some 20 metres high surrounded by several stone buildings. From the top of the mill one could easily reconnoitre the surrounding area for enemy troop movements. For an experienced military commander such as Nils von Schoultz, Windmill Point could have served as a perfect site for establishing a beachhead on enemy territory until reinforcements arrived.

The British and Canadians quickly collected a large force of regular soldiers and militia numbering nearly 2,000 men. On Tuesday morning of that week the two sides engaged in a fierce rifle and musket battle. Finding the insurgents too strongly entrenched, the Canadians retreated to await the arrival of their heavy artillery.

As the week progressed, the situation for the insurgents became increasingly hopeless. The Canadians had not risen in rebellion against their colonial government. In fact, the very opposite was happening as hundreds joined their local militias to repulse this invasion. Some of the Americans either escaped to the United States or were captured while trying to leave. Many suffered from wounds incurred in the Tuesday battle. The weather turned very cold.

Although the insurgents held their position for five days, no reinforcements came. What was particularly frustrating for the hard-pressed American invading party throughout the week was to look across the river and see thousands of Americans, most of whom were sympathetic to the cause of “liberating” Canada from British rule, standing along the shorelines watching events unfold on the Canadian side.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

On Friday afternoon, the British artillery began bombarding the American positions. The insurgents began to either surrender or attempt to escape. Von Schoultz himself was captured late Friday evening as he hid in bushes along the river bank.

Many of the battles fought in 1838 between American raiding parties and the British/Canadian forces were little more than bloody skirmishes lasting less than an hour. The American invaders lacked the discipline of the British regular soldiers or the determination of Canadian militia members defending their own homes.

It is to von Schoultz’s great credit as a military commander that the rag-tag fighting unit he led (some of whom were only 14 years old and none of whom had any real military experience) held out for five days in a desperate situation after sustaining heavy initial losses.

The prisoners spent one night in Fort Wellington. They were then transferred by steamer to Kingston and the military prison at Fort Henry where the government held its courts-martial.

A young Kingston lawyer, John A. Macdonald, had been retained to give legal advice to one of the other prisoners. Macdonald met von Schoultz at this time and gave him some legal advice for conducting his defence at his court-martial. Von Schoultz insisted on pleading guilty.

At his court-martial, von Schoultz made a distinct impression on the British regular soldiers and others of his Canadian captors. As leader of the insurgents, von Schoultz assumed all responsibility for the tragedy at Windmill Point. He made no attempt to defend himself except to say he had treated his wounded prisoners well. He never displayed any bitterness and refrained from censuring those who had let him down with promises of reinforcements.

A total of eleven of the prisoners were executed. Sixty others were sent into exile to the penal colony of Van Dieman’s Land (present-day Tasmania).

The first of the insurgents to hang was Nils von Schoultz. As a mark of respect for his military background, von Schoultz was the only one of the eleven to be hanged and buried at Fort Henry.

Throughout the time of his capture until his execution, von Schoultz maintained his posture of being a former Polish officer. It was perhaps essential that he continued to do so. The fact that von Schoultz had a Scottish wife and that he had abandoned her and their children would hardly have improved his situation. It would probably have dissipated the respect he had been able to create among his captors as an honourable, albeit misguided, lover of liberty.

For more than 130 years, Canadian and American historians regarded von Schoultz as the former Polish army officer he had portrayed himself to be. It was not until 1971, when Ella Pipping, von Schoultz’s great-granddaughter, published a biography on her ancestor that historians learned that von Schoultz was actually a Finn by birth, a Swedish national and that, in fact, this “Polish” freedom-fighter had only spent some six months in Poland.

Macdonald drew up von Schoultz’s will. Money was left to the Roman Catholic college in Kingston and to families of the Canadian militiamen killed at the Windmill. He wrote a last letter to friends in Salina. There was, however, no last letter to his family in Sweden.

Macdonald spent considerable time talking with von Schoultz. This “Polish” insurgent left a deep impression on his legal counsel. According to Donald Creighton, in his biography of Canada’s first prime minister, the Windmill Point incident conceived in Macdonald’s mind the problem of how a divided Canada could defend itself from its southern neighbour and the need for some kind of union of Britain’s North American colonies. Macdonald would remember von Schoultz for the rest of his life.

The final tragic irony to the von Schoultz raid was that 1838 was also the year Lord Durham, while Governor of Lower Canada, analyzed the administration of the British colonies of Upper and Lower Canada. His report to the British Government in 1839 recommended changes in the political administration of these two colonies that came to result in self-government for Canadians within the British Empire.

The battle at Windmill Point, therefore, was a bloody footnote in the political evolution taking place in British North America and can be viewed as an example of uninvited outside forces presuming to dictate the development of the emerging Canadian nation.

To his fellow prisoners and to the British officers and captors. Nils von Schoultz left the memory of a Polish officer of impeccable manners, immense charm and noble dignity in the way he accepted his death sentence. The report on his execution read: “He maintained his demeanour to the last.” Everyone remembered him as a gallant freedom-fighter who had been tragically misinformed about conditions in Canada.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!