Arthur’s Secret

Chester Alan Arthur, twenty-first president of the United States, was an accidental president.

He was also an accidental vice-president.

Chester Arthur may also have been a Canadian citizen and, therefore, ineligible to hold the offices of president and vice-president.

He happened to be in the right place at the right time when Republican bosses were feverishly scrambling for a compromise running mate for James A. Garfield of Ohio. The 1880 Republican national convention was hopelessly deadlocked by feuding factions. One faction sought a third term for Ulysses S. Grant, but its efforts were in vain. After thirty-six ballots the delegates turned to a dark horse—James Garfield.

Article continues below...

-

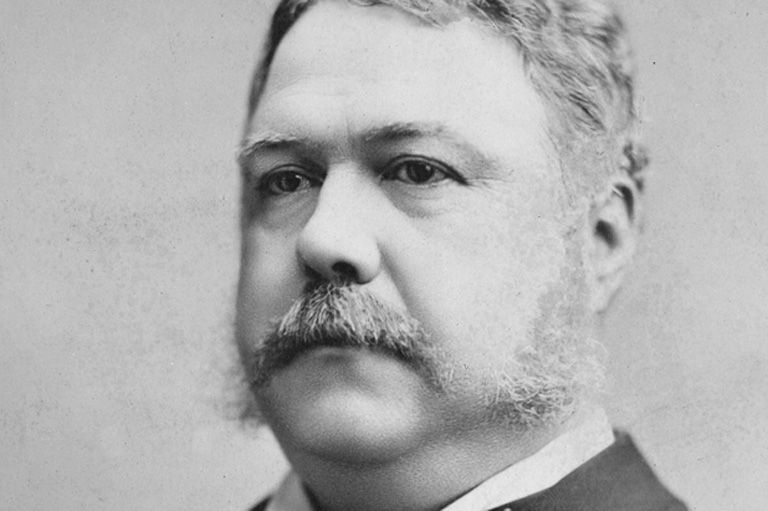

Circumstance, not design, brought Chester Alan Arthur to the presidency of the United States. He had been vice-president for only a few months when an assassin’s bullet critically wounded President James A. Garfield in the summer of 1881. In September, with Garfield’s death, he automatically became president. Yet even before his vice-presidential nomination, questions were being raised about his citizenship.Library of Congress / LC-USZ62-80432

Circumstance, not design, brought Chester Alan Arthur to the presidency of the United States. He had been vice-president for only a few months when an assassin’s bullet critically wounded President James A. Garfield in the summer of 1881. In September, with Garfield’s death, he automatically became president. Yet even before his vice-presidential nomination, questions were being raised about his citizenship.Library of Congress / LC-USZ62-80432 -

Four American presidents have been assassinated. James Abram Garfield, twentieth president of the United States, was the second. He was a compromise candidate at the 1880 Republican national convention, and narrowly won the 1880 election. On July 2,1881, he was shot in a Washington railway station by Charles J. Guiteau, a jobless man who had been rebuffed in his appeals to the president for a patronage appointment.National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution / NPG.77.187

Four American presidents have been assassinated. James Abram Garfield, twentieth president of the United States, was the second. He was a compromise candidate at the 1880 Republican national convention, and narrowly won the 1880 election. On July 2,1881, he was shot in a Washington railway station by Charles J. Guiteau, a jobless man who had been rebuffed in his appeals to the president for a patronage appointment.National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution / NPG.77.187 -

William Marcy Tweed, known as “Boss” Tweed, was a powerful force in New York City politics in the middle of the nineteenth century. Through various machinations he and his cohorts managed to seize control of the city treasury and plunder it of millions. After an expose in the New York Times, he was tried and convicted on charges of forgery and larceny, and sent to prison in 1873.National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution / NPG.77.314

William Marcy Tweed, known as “Boss” Tweed, was a powerful force in New York City politics in the middle of the nineteenth century. Through various machinations he and his cohorts managed to seize control of the city treasury and plunder it of millions. After an expose in the New York Times, he was tried and convicted on charges of forgery and larceny, and sent to prison in 1873.National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution / NPG.77.314 -

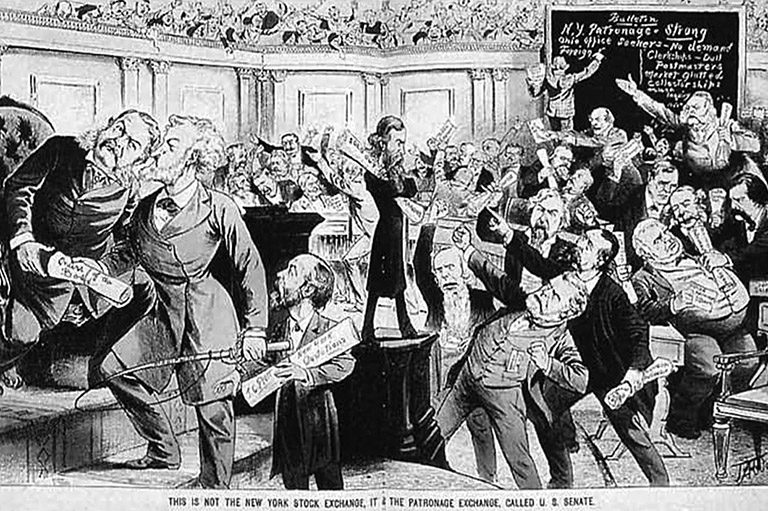

Cartoon, from Puck magazine, April 13, 1881. Arthur’s beginnings in politics were in New York, where in 1871 he was appointed collector of customs for the port of New York, a place conspicuous for flagrant abuses of the spoils system. Some people feared that as vice-president (the period of this cartoon), Arthur would have a pernicious influence on government. As president, however, he undertook reforms that removed patronage from the civil service.Library of Congress / LC-USZC4-6400

Cartoon, from Puck magazine, April 13, 1881. Arthur’s beginnings in politics were in New York, where in 1871 he was appointed collector of customs for the port of New York, a place conspicuous for flagrant abuses of the spoils system. Some people feared that as vice-president (the period of this cartoon), Arthur would have a pernicious influence on government. As president, however, he undertook reforms that removed patronage from the civil service.Library of Congress / LC-USZC4-6400

Party bosses then turned to selecting a vice-presidential running mate to round off the ticket. Needing to appease the defeated faction, they offered second place on the ticket to New York delegate Levi P. Morton, but he allowed the cup to pass from his lips. The offer was then made to Chester Arthur, and he accepted.

Arthur had never sought nor run for public office in his life. He was the consummate backroom politician who, early on, caught the eye of the big-city political bosses. But the Garfield-Arthur ticket went on to defeat Democrats Winfield Scott Hancock and William H. English in the 1880 election (though by fewer than ten thousand votes) and Chester Arthur found himself vice-president of the United States.

James Garfield’s presidency lasted only 199 days. On July 2, 1881, he was wounded by an assassin’s bullet in Washington. He died ten weeks later from septic poisoning with the bullet still lodged in his body.

Chester Arthur was sworn in as president of the United States the day Garfield died—September 19, 1881. He was probably not qualified under the U.S. Constitution to serve as either president or vice-president.

Article II of the Constitution stipulates: “No Person except a natural horn Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States … shall be eligible to the Office of President.” Article XII of the Amendments to the Constitution states: “But no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States.”

It appears Chester Alan Arthur did not meet the Constitution’s statutory requirements.

Chester Arthur was most likely a citizen of Lower Canada, a British subject, born in Dunham Flats, Quebec, near the Vermont border. His father, William, was born in 1796 in Ballymena, County Antrim, in what is now Northern Ireland, where the MacArthurs, as they were originally called, immigrated from Scotland. Arthur’s grandfather, Gavin MacArthur, changed the family name to Arthur to set himself and his heirs apart from the Catholic MacArthurs. Chester Arthur’s father was named after the Protestant King William of Orange.

In 1818, at age twenty-two, William Arthur left Ireland forever and sailed from Derry to Trois-Rivieres, Quebec, in search of a better life. From Trois-Rivieres he moved to Upper Mills (now known as Stanbridge), and then to Dunham Flats, where he obtained a teaching position.

There is no record that Arthur’s father ever attempted to become a United States citizen, even though his dual jobs as a teacher and itinerant preacher took him back and forth across the border from Quebec to Vermont and New York. Arthur’s mother, Malvina Stone, a descendant of English settlers in New Hampshire, was a British subject living in Dunham Flats.

William Arthur and Malvina Stone eloped. They ran away to East Berkshire, Vermont, and were married by a Methodist clergyman. On April 12, 1821, they renewed their marriage vows in the Episcopal Church of All Saints in Dunham Flats.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In 1823, the Arthurs set up housekeeping in Burlington, Vermont, and the next half-dozen years are a blur of moves to new pastoral duties (William had become a Baptist) and teaching positions. In addition to Burlington, Dunham Flats, and Stanbridge in Quebec, the Arthurs also lived in Jericho, Richford, Waterville, and North Fairfield, Vermont. Given the sheer number of residences they had, it is difficult to pin down who of their six children was born where.

Even the official arm of the U.S. government—the U.S. Information Service—is unclear as to the details of Chester Arthur’s birth. The USIS office in the embassy in Ottawa responded to my query with the answer: “You’ll note that they (The Presidency from A to Z published by Congressional Quarterly) indicate President Arthur was born on October 5, 1830. Two other sources indicate that the actual year of birth was 1829.” One of those two sources, though unnamed by the USIS office, alleged that Chester Arthur changed the year of his birth “out of vanity” alone, but this seems highly unlikely.

A son—likely William Chester Alan Arthur—was born in his grandparents’ house in Dunham Flats in Lower Canada in 1829, though there is no record of his birth in present-day Dunham, Quebec. (Records of the period were destroyed in a fire.)

The next year a second son—likely Chester Abell Arthur—was born in North Fairfield, Vermont, but he died in infancy. Again, no official record exists of the death, though relatives later attested the child’s body was sold to a medical school as a cadaver for dissection.

In my search for evidence regarding Arthur’s birth, the office of the secretary of state in Vermont’s capital, Montpelier, responded: “There is no record in this office showing the births and deaths of the children of William Arthur and Malvina Arthur from Jan. 1, 1822, to Jan. 1, 1841.” Similarly, the town clerk in Fairfield wrote: “[I] do not find recorded, therein, between the years A.D. 1825 and A.D. 1835, the birth of any child named Chester A. Arthur.”

Could the future U.S. president have appropriated his brother’s birthplace so he could claim U.S. citizenship?

An in-law of the Stone family wrote later: “C.A. Arthur was born in Canada. I am strongly of the opinion that the son Chester Abell Arthur died in Burlington. [I will swear that the] present Arthur assumed the name of his dead brother. There is no doubt that the son who died in Burlington is the one said to be born at Fairfield.”

An elderly aunt of Arthur’s said he was “born on British soil” and “there is no doubt that the son who died at Burlington is the one said to be born at Fairfield.” Lindal Corey, a surveyor and longtime Dunham Flats resident, swore before he died that William and Malvina Arthur had a son born in Dunham Flats before they began their nomadic treks through Vermont and New York. Chester Arthur attended Union College in Schenectady, New York, but the college kept no record of birthplaces.

Even Burke’s Presidential Families of the United States of America reports that Chester Arthur “was probably born in Canada.”

But well before his advance in politics, Arthur was claiming American citizenship. On being called to the New York bar, he swore before William A. Dusenberry, commissioner of deeds, that he was “a native-born citizen of the United States … of the age of twenty-one years, and a resident of the First Judicial District of the Supreme Court of the State of New York.”

Nonetheless, Arthur’s pedigree was challenged in 1880 when he accepted the vice-presidential nomination. Republican bosses insisted he provide proof of birthplace and citizenship. At first, he was unable to name his birthplace, but party leaders insisted he name a place before he wrote his acceptance letter.

Chester Arthur told his associates he was “going fishing” and would return with the requested letter. He did not go fishing. Instead, he went to Montreal with a friend to search records to see if any existed showing he was born in Canada.

Finding none, he deemed it safe to name some out-of-the-way place in the U.S. He chose North Fairfield where his deceased infant brother had been born and, thus, made it appear he was a native-born U.S. citizen.

Americans like to place their presidents—especially dead ones—high on pedestals. But there is little doubt in some quarters that Chester Arthur was a venal person capable of committing any duplicitous deed to achieve his political ends.

He was a creature of machine politics and a protégé of the notorious backroom puppet master William Marcy “Boss” Tweed. He moved up through Republican patronage ranks very swiftly once he had caught Tweed’s eye. As a New York state senator, Tweed created through legislation a totally unnecessary and redundant legal opening that paid Chester Arthur $10,000 a year in 1869 as counsel to the commissioners of the board of taxes and assessments.

In 1871 Arthur was appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant to one of the most coveted offices in all of government—collector of the port of New York. He supervised more than one thousand officials who collected about two-thirds of the nation’s revenue from tariffs, and enjoyed an annual salary of $40,000 a year.

Arthur was fired by President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1878 as a symbolic gesture in the president’s campaign against the spoils system. Despite this, Arthur left office with $3 million saved from his salary over a seven-year span.

As president, however, he surprised his detractors and confounded his ward-heeling Republican backers. He turned out to be a reformer, which burned his bridges with backroom kingmakers. He vigorously pursued prosecutions of post-office scandals in which several party supporters were implicated.

In 1883 he signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, which all but eliminated patronage appointments and replaced them with civil service exams for most federal jobs. He also attempted to reduce tariffs, cut the federal debt, and modernize the U.S. Navy.

He looked every inch the aristocratic father figure Americans looked for in their chief executives, too. He was seen as a Victorian grandee—always in a Prince Albert coat, ascot tie, a fresh flower in his buttonhole, and a silk handkerchief in his vest pocket.

But in the end, the Republican supporters he alienated with his reforms got even. He lost his bid for renomination in 1884, and the Republicans lost the White House to Grover Cleveland, the first Democrat to be elected president since before the Civil War. Cleveland, 250 pounds, handsome, beer drinking, cigar smoking, a hunter and fisherman, won the 1884 election by only 29,704 votes out of the almost ten million cast.

Chester Arthur, the “Gentleman Boss,” returned to New York and resumed his law practice. He kept secret the fact he had long suffered from Bright’s disease, or nephritis—a life-threatening kidney ailment. He died in New York City on November 18, 1886.

At the time of his death, he was looked upon as the most effective U.S. president since Lincoln. Not bad for a Canadian, eh? Or, as Americans might say: not bad for a Canadian, huh?

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!