Shooting Arrows

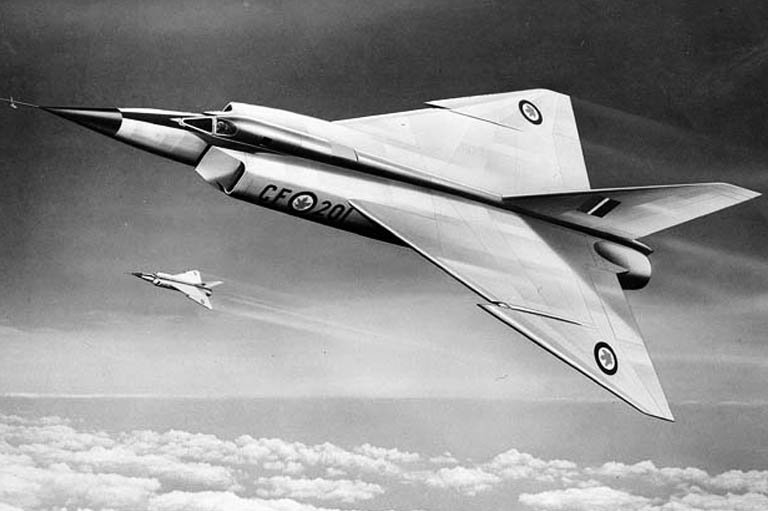

The time-etched film begins with an overhead shot of a white triangle moving down a grey, tire-streaked runway. the viewpoint then cuts to a camera on the ground, showing a rapidly approaching airplane, with flames bursting from its exhaust, the jet shoots past the camera and into the blue sky. Moments later, viewed through a chase plane, we follow the fighter jet as it roards through the air and then comes in for a landing.

Suddenly, a voice cuts into the mix.

“This is the Avro Arrow,” narrator Lou Wise says proudly. “Canada’s entry into the supersonic era.”

This was the Arrow’s maiden flight, as seen in the introduction to Supersonic Sentinel a twenty-three-minute film documenting the creation of the historic aircraft.

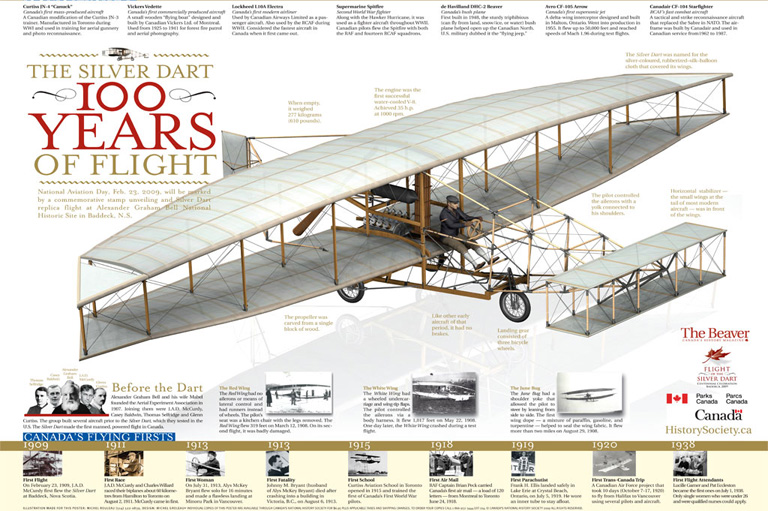

Produced by A.V. Roe Canada Limited’s photographic department, the film is a valuable record of the CF-105 Arrow, an aircraft that is seen by many as the high-water mark in Canadian aviation. It was, after all, on its way to becoming, at the time, the fastest plane that ever flew. And today, fifty years after the project’s cancellation, the Arrow remains a subject of considerable fascination to the public — a source of seemingly endless debate on what Canada’s role in world aviation might have been had the aircraft not been scrapped.

What has possibly helped keep the debate alive is the fact that people today can watch films and see photos of the remarkable-looking plane, with its delta wings, needle nose, and sleek profile. This wasn’t supposed to happen. Early on, there were official attempts to wipe the Arrow from public memory.

Lou Wise, the head of Avro’s film and photo department, remembers clearly the order that came down a few weeks after the federal government announced the cancellation of the project on February 20, 1959.

“The order was that everything was to be destroyed,” recalls Wise, who, at eighty-seven, still conveys a sense of disbelief about what happened. “Not just airplanes, but drawings, photographic reproductions of drawings, all photography that related to the Arrow — and we had made a large number of sixteen-millimetre films in addition to thousands and thousands and thousands of still camera negatives.”

For a man who had spent a good part of his career recording the progress of the Arrow — and was intensely proud of it — the order was devastating. With a heavy heart, Wise pondered what to do.

It didn’t take him long to make a decision. He called his staff together and gave them his carefully worded instructions. His orders would ultimately impact how future generations would remember this pivotal moment in aviation history.

In 1953, with the Cold War heating up, the Canadian government commissioned A.V. Roe (later known simply as Avro) to build a supersonic, missile-carrying jet interceptor to patrol the skies for Russian bombers. Avro had already built Canada’s first jet fighter — the CF-100 Canuck all-weather interceptor — which went into service in 1953. But the Royal Canadian Air Force felt it was already obsolete, as the Russians were developing faster aircraft. A.V. Roe, a subsidiary of the Hawker Siddeley Group — whose origins stemmed from Victory Aircraft, manufacturer of the famed Lancaster bomber — was up for the challenge.

Soon, the company had five aircraft, arguably the most advanced jet fighters of the day, ready for test flights. The test flights were conducted at the company’s facility in Malton, Ontario, in the northeast corner of what is today Toronto Pearson International Airport. People who lived in the area were often treated to impromptu air shows at a time when jet aviation was very new.

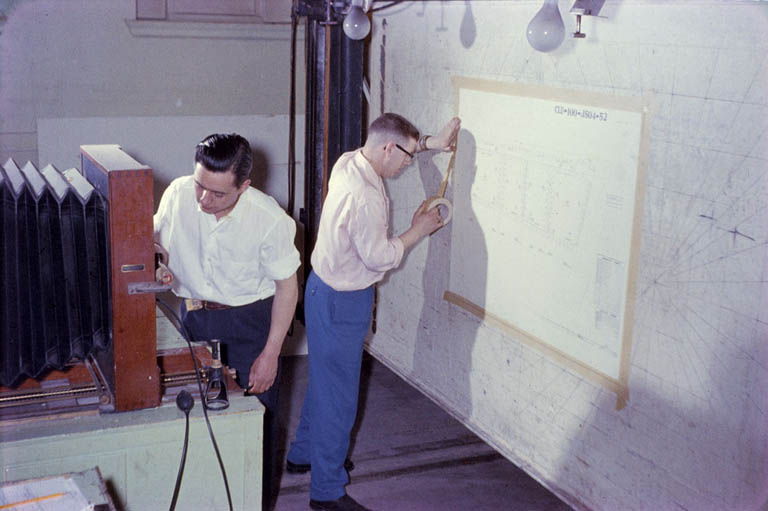

Avro’s photo department documented every step of the way.

“There was literally nothing that went on without one or two of our cameramen being assigned to cover it,” says Wise, seated in a room of his Toronto home that’s filled with Avro memorabilia. The photography department was part of Avro’s engineering division. Its job was to take X-ray photos of aircraft components, shoot stills of complex details, and document the various stages of testing.

The Avro project showed great promise. However, out-of-this-world events were unfolding elsewhere that had ominous repercussions for both the aircraft and its parent company.

In a strange stroke of coincidence, the day the Arrow was first publicly unveiled — October 4, 1957 — also happened to be the day the Russians launched Sputnik I, the world’s first satellite. It was extremely bad timing for what was supposed to be Canada’s proudest aviation moment to date — the public rollout of a flashy new aircraft. With Sputnik orbiting overhead, there was little room for the Arrow in the next day’s newspapers.

Yet Avro’s staff had much to be excited about. Test flights of the first five planes showed great promise. A sixth plane, the first to be equipped with the Orenda Iroquois, an advanced turbojet engine designed to exceed a then-record speed of Mach 2, was just weeks away from flight. (Mach is the speed of sound, so Mach 2 is twice the speed of sound.) The Arrow seemed on target to deliver on a promise to speedily intercept and shoot down invading Soviet planes armed with nuclear bombs.

But the launch of Sputnik sent the Arrow’s relevance into a tailspin. Sputnik opened up the possibility of a new kind of war, one that, with the push of a button, could see atomic missiles launched from satellites in space.

Canadian politicians saw trouble. The nation’s technological triumph was threatening to turn into a great white flying elephant.

Making matters worse, costs for the Liberal-launched program were rapidly rising; early estimates of $1.5 million to $2 million per plane had spiralled to more than $10 million each. One reason for the increased per-unit cost was that the governing Conservatives had reduced the number of Arrows to be built to 100 from the 500 to 600 that were originally anticipated. This meant that the huge research and development expense would be spread over fewer planes.

With soaring costs and the superpowers now focusing on missile warfare, John Diefenbaker’s Progressive Conservative government came to a momentous decision. At 11 a.m. on February 20, 1959, a day that would become known as “Black Friday,” Diefenbaker rose in the House of Commons to announce that “the government has carefully examined and re-examined the probable need for the Arrow” and ultimately determined “the development of the Arrow aircraft ... should be terminated now.”

The decision immediately put more than 14,000 Avro employees out of work and directly affected thousands more who worked for outside suppliers.

Not only was the program to be terminated, the planes were to be cut to pieces and sold off as scrap metal. The destruction of the planes has long fuelled conspiracy theories, such as that Diefenbaker was pressured by a U.S. administration that had conspired with the American aircraft industry, which was lobbying to sell its own planes. However, there is little evidence for this view. The official word was that the planes were destroyed to prevent advanced technology from getting into the hands of the Soviets.

Like everyone else connected with the Arrow, the photography department went into shock when the cancellation was announced.

“I don’t think that any of us truly believed that the project would be cancelled, because we had so much faith in the aircraft,” recalls Wise. “I suppose we all went home with long faces and told our wives we were laid off, which was about the same as being fired. The program had been cancelled and we had nowhere else to go.”

It turned out that Wise and a few others in the photo department were asked to stay on as the project wound down. A few weeks after Black Friday, word came down from Ottawa to destroy the aircraft and all traces of it, including film and photos.

Wise knew this was the wrong thing to do.

“I figured it was too valuable a collection," he said of the Arrow’s film and photo record.

“An awful lot of work on the part of a lot of good people had gone into it, and I guess I just didn’t see the sense in destroying it all.”

Quickly considering his options, Wise called a meeting of the remaining photo staff. He told them what they had been ordered to do. And then he told them they weren’t going to do it.

“I said, ‘We’re not going to junk all this stuff. We’re going to go through it and pick out some to cull.’” They did in fact destroy hundreds of images, but they were mostly duplicates of existing ones. “This was so I could look people in the eye and say, ‘Yes, we’ve destroyed negatives.’ I never did say we destroyed all the Arrow negatives. Just that we’d destroyed negatives.”

Some of what remained ended up in the private collections of staff, but the bulk of it was quietly filed away in company drawers and filing cabinets.

With his job on the line in any case — although he remained with Avro for a few more years, his job disappeared when the company went defunct in 1962 — Wise was not overly worried about the consequences of disobeying orders.

“I didn’t anticipate that anybody would come around and say, ‘Show me all the empty drawers.’”

When Wise left and Avro went out of business, the photographic material was still in the defunct company’s filing cabinets.

That material was moved to the offices of Hawker Siddeley, which had taken over Avro’s assets. Eventually, officials at Hawker Siddeley passed the collection on to the National Archives in Ottawa, where it has remained ever since.

Given the public’s ongoing fascination with the Arrow, the images have not been gathering dust. Many of the photos have been used to illustrate the dozens of books that have been written about the Arrow. Supersonic Sentinel — the film narrated by Wise that helped earn him the nickname “Voice of Arrow” — continues to be popular.

“That film is seen by so many people,” says Wise. “I’ve got it on DVD. And I’ve used it at a lot of meetings over the years. There’s a great host of people out there who won’t let the Arrow die.”

The film got a new life when clips from it and other Avro productions appeared in the 1997 docudrama The Arrow, which starred Dan Aykroyd as Avro president Crawford Gordon. Wise even makes a cameo of sorts. One early scene uses clips from The Jet Age, an overview of prior Avro accomplishments, complete with the unmistakable, measured, baritone voice-over work of Wise himself.

Wise eventually moved on to a twenty-two-year career in the Toronto Board of Education’s media department, and after “retirement” he took off on a third career as an aerial photographer, flying a Piper Cherokee.

But his heart is still close to the Arrow. Today, fifty years after Black Friday, he, like many others who’d worked for Avro, continues to lament the company’s demise. “I still believe it was a great misfortune for this country, ” he says. “Avro was a long, long way ahead of any competition in the States and U.K.” The cancellation virtually “wiped out” Canada’s aviation industry, he contends.

The planes are long gone, but thanks to Lou Wise and the staff of Avro’s film department the images and memory of the Arrow live on.

“Jetographic” Moments

Avro had one of the largest industrial photo and film departments on the continent, and its photographers had access to the most advanced cameras and equipment of the day.

The original role of the photographers and filmmakers was to work side-by-side with engineers testing the functions of the aircraft. Their state-of-the-art high-speed film could, for instance, capture the action of explosive bolts forcing open a cockpit’s ejection canopy.

Ron Northcott joined the firm in 1954 and become one of a half-dozen photographers in the country trained in high-speed photography. He used a Kodak camera that shot as many as 3,000 frames per second on one-hundred-foot-long rolls of film (a modern movie camera typically shoots twenty-four to thirty frames per second).

To get the camera up to speed, Northcott had to start filming long before the actual event. “All the action was on the last bit of film,” said Northcott. “You’d have ninety feet of build-up and ten or twelve feet of action.”

The detail captured by the high-speed camera was essential and exceptional. “You could actually read the writing on the side of the rocket crystal-clear,” said Northcott, recalling some work he had done on Avro’s earlier CF-100 rocket pods. With no Photoshop software available in those days, department staffers painted out dust motes and other imperfections in the final prints by hand.

Later, the department expanded into public relations, shooting images to impress both their RCAF client and a curious, patriotic nation. Its success in this played a large part in the Arrow’s long-lasting mystique.

“Avro was very, very good at PR. They knew how to film product,” says Paul Cabot of the Toronto Aerospace Museum. Given the volume of PR material distributed, it’s somewhat surprising to learn that one man, Verne Morse, was responsible for most of those images.

“No exaggeration — virtually every picture that was released for publication was taken by me, I’m proud to say,” Morse said from his Orlando, Florida, home. (Like many Avro staffers, Morse moved on to a job in the U.S. after the program was cancelled.)

With most of the original blueprints long-since destroyed, Morse’s photos were essential in helping the Toronto museum’s volunteers accurately construct their full-scale Arrow replica, unveiled in 2006. The replica, which does not fly, is on display at the museum. — A.B.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Help support history teachers across Canada!

By donating your unused Aeroplan points to Canada’s History Society, you help us provide teachers with crucial resources by offsetting the cost of running our education and awards programs.