The Write Stuff

Over the past hundred years, The Beaver has been led by editors from a variety of backgrounds, including public relations, journalism, fiction writing, accounting, popular history, art history, theatre, and museums. Here are the stories of the people who have steered the magazine:

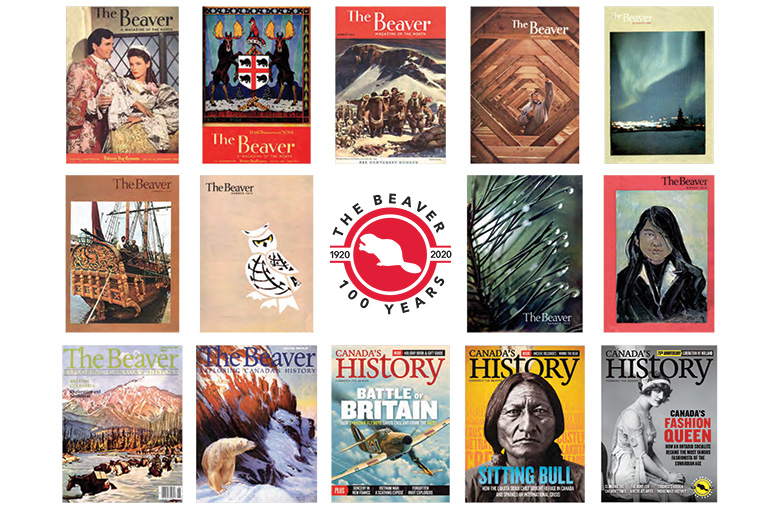

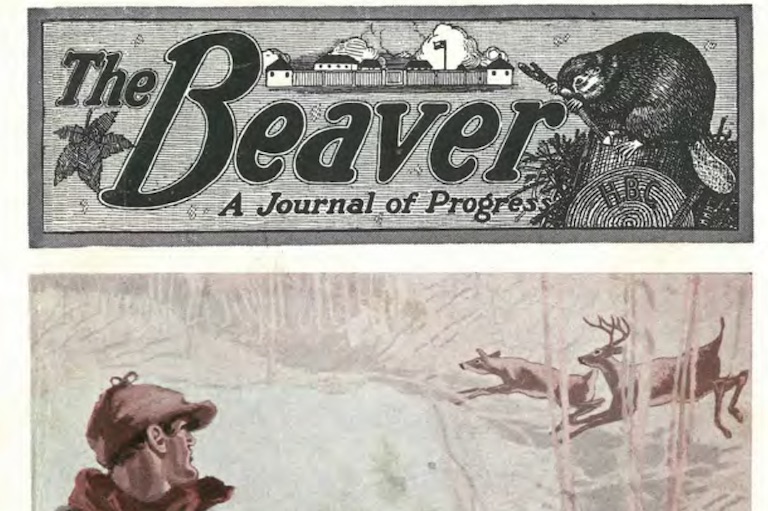

Clifton Thomas, a public-relations professional from Chicago, was the magazine’s first editor. Sent to Winnipeg to run the Hudson’s Bay Company’s 250th-anniversary celebrations, he stayed to become head of the publicity department and its new company newsletter, The Beaver: A Journal of Progress. The October 1920 inaugural issue was just a little bigger than a theatre program and featured HBC governor Sir Robert M. Kindersley on the cover.

Thomas described his boss in breathless prose: “Servants of the Company heard from our Governor’s own lips that he was not to the manor born but a self-made man.” The rest of Thomas’s inaugural issue was devoted to “the remarkable success” of the anniversary celebrations.

Thomas made the most of his time in Manitoba. A 1923 photo shows him hunting moose while decked out in a Hudson’s Bay Company point blanket coat. However, “opportunity sometimes ruthlessly severs the most pleasant associations, even while opening the door to a larger future,” Thomas wrote in August 1923 as he announced his move back to the United States.

The magazine then fell into the hands of forty-one-year-old Robert Watson. An HBC employee since 1917, the Scottish-born accountant spent his spare time writing bestselling novels and specialized in tales of adventure and romance.

Watson regaled the magazine’s readers with some of his own escapades, including a lighthearted account of getting lost on a deer hunt in the Rockies. He also wrote about his travels by train to New York City and Philadelphia. In that article, titled “So This is America!,” he described himself as a “country bumpkin.”

Under Watson, the magazine took on a different look and feel: “The Beaver turned away from American-style corporate publicity toward a more literary approach,” wrote Robert Geller in his book Northern Exposures. The Beaver’s typeface changed to Caslon from Bookman, and more historical articles appeared on its pages.

The subhead “A Journal of Progress” eventually disappeared, as did the mission statement “Devoted to the Interests of Those Who Serve the Hudson’s Bay Company.” After ten years Watson left the company for the bright lights of Hollywood, California, where he worked in the motion picture industry. He died there in an automobile accident on January 13, 1948.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

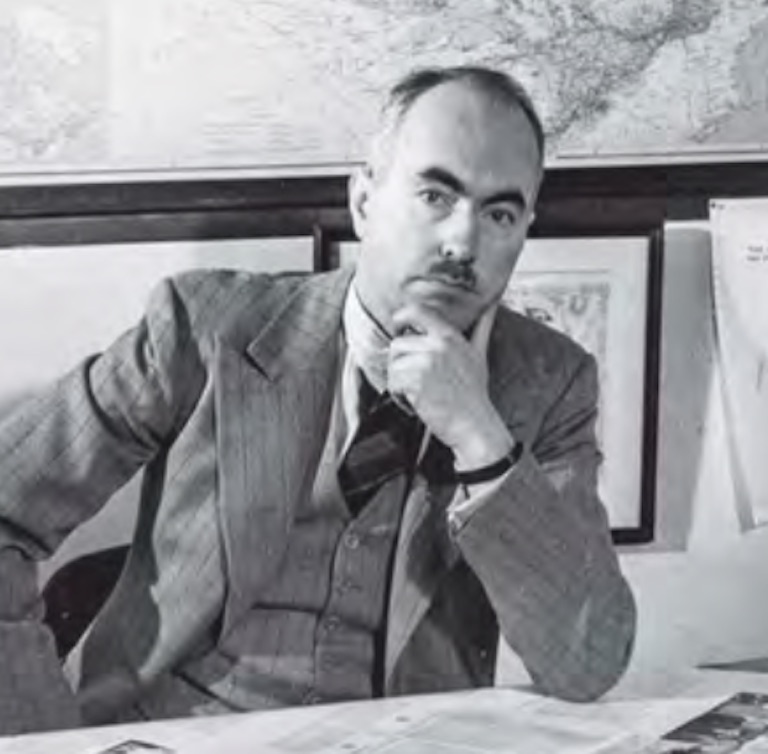

Thirty-three-year-old Douglas MacKay took over as editor in 1933. Almost immediately, the former PR director for the HBC’s Canadian Committee gave the publication a new subhead — “A Magazine of the North” — and expanded its page size from digest size to a standard magazine format. A former journalist for the Canadian Press in Ottawa, MacKay was no slouch as a writer, either. He spent his evenings writing The Honourable Company: A History of the Hudson’s Bay Company (1936).

His access to the HBC’s London, England-based archives gave him an edge over others who had tried to write about the notoriously secretive firm. While his prose flattered the company, the HBC’s board of directors was not amused. “The board sent the Canadian Committee ‘an expression of surprise and disappointment that the Committee should have permitted a history of the Company to be written and published in the United States of America by a member of the Company’s staff without the knowledge of the Board,’” wrote Deirdre Simmons in Keepers of the Record: The History of the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives.

Despite this slap on the wrist, MacKay kept both his job and his work ethic. He enhanced the magazine’s visual appeal by commissioning professional photographers. He also made broadcasts on historical topics for the CBC, and The Beaver itself was heavy with his historical writing.

MacKay somehow had time for hobbies, too. An avid downhill skier, he promoted the sport, and it was no accident that HBC point blanket coats were the official outfits of the 1936 Canadian Olympic ski team.

“He was going places,” said his obituary in Canadian Ski Yearbook. “Hollywood had bartered for the film rights of his book on pioneer days of the Hudson Bay Company and he was ‘getting a tremendous kick’ as he put it, out of his visits there.” Sadly, MacKay’s high-achieving life came to a sudden end when he died in an airplane crash in Montana on January 10, 1938 — the date of his thirteenth wedding anniversary.

Left to mourn him were his widow, Alice, and their three young children. Alice MacKay, also a journalist, filled in after her husband’s death. The former Alice Higgins had been a reporter for the Ottawa Journal at a time when few women were in that business. She met her husband-to-be when both were working in the Ottawa press gallery. Canadian Ski Yearbook described Alice MacKay as “a girl as capable as [her husband] as a journalist and writer.”

Along with taking on the duties of magazine production, Alice MacKay also worked for the publicity branch of the HBC and was the company’s liaison with Hollywood.

During the year and a half she spent at the helm of The Beaver, there were some subtle changes. For instance, she identified the magazine’s few women contributors by their own names, including Maud Watt, the adventurous wife of HBC post manager J.S.C. Watt. (After Alice MacKay left, Watt continued to write for The Beaver; but her byline reverted to Mrs. J.S.C. Watt, as was the custom of the time.) MacKay left the HBC in 1939 to work for James Richardson and Sons.

After MacKay’s departure, Clifford Parnell Wilson became the editor. Wilson had written a number of popular-history articles for The Beaver and had reorganized the HBC’s historical exhibit in its Winnipeg store. He became the longest-serving editor to date — eighteen years.

Under his steady hand, The Beaver built on the MacKays’ work of focusing on northern and fur-trading history. Wilson attracted high-profile contributors, including anthropologist Margaret Mead, thereby sealing the magazine’s reputation as a serious publication. He transferred company news to a new in-house newsletter called the Moccasin Telegraph. Wilson also took on the MacKays’ Hollywood duties. Among other things, he watched Cecil B. DeMille shoot scenes for the 1940 historical drama North West Mounted Police. Wilson retired in 1957.

Taking his place was Malvina Bolus, who had previously been with the Canadian Geographical Journal in Ottawa. Born in the Falkland Islands, she came with an impressive resumé. Bolus had served as personal secretary to Agnes Macphail, Canada’s first female MP, as personal assistant to Canada’s top wartime generals at the Canadian Military Headquarters in London, England, and as private secretary to Vannevar Bush, the American government’s top science administrator.

“The circulation of the magazine increased substantially under her leadership as Bolus widened the scope of the magazine beyond its historical focus, introducing such subjects as art, nature, and archaeology,” states her biographical sketch in the Archives of Manitoba.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

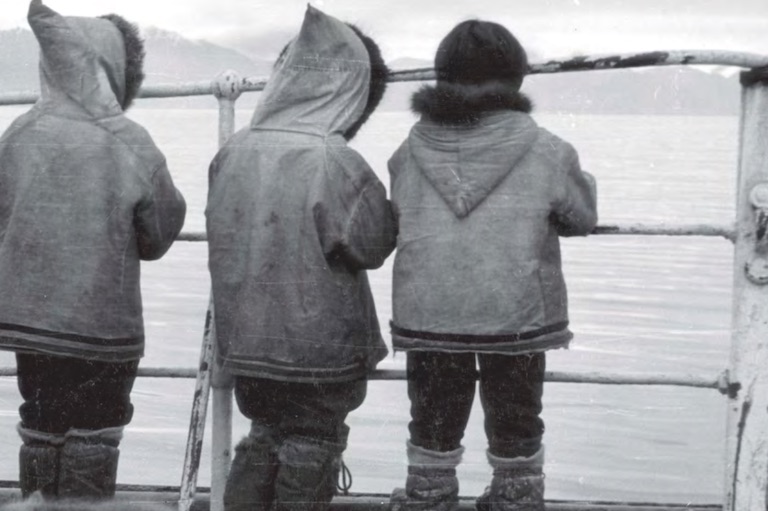

She had a particular interest in Inuit art, language, and folklore. “Under her editorship The Beaver became one of North America’s foremost historical publications,” adds the online Dictionary of Falklands Biography. By the time Bolus retired in 1972, she had received numerous awards and distinctions, including the Medal of Service of the Order of Canada.

Helen Burgess was hired by Bolus in 1970 as assistant editor and replaced her two years later.

“Throughout her tenure, Helen Burgess preserved and enriched the traditions of The Beaver: she broadened its subject range, placing a greater emphasis on social history,” wrote A. Rolph Huband, the HBC’s vice-president and secretary, upon her retirement in 1985.

Christopher Dafoe, grandson of journalist John Wesley Dafoe, arrived in 1985.

Dafoe, an actor, author, scriptwriter, and journalist, refined the magazine’s historical focus, changing the subhead to “Exploring Canada’s History.” The magazine also increased the number of issues to six per year from four.

Dafoe was the first of the magazine’s editors to write his own regular column, entitled “Explorations.” Dafoe left in 1997.

Shirlee Anne Smith, the first Keeper of the HBC Archives in Canada and head of The Beaver’s editorial committee, served as interim editor for a few months until the hiring of Annalee Greenberg late in 1997.

Greenberg, an editor, freelance journalist, and contract publisher, held the position until 2006.

During her tenure the magazine underwent significant design changes and adopted the subhead “Canada’s History Magazine.”

Former Winnipeg Free Press publisher Murdoch Davis and mystery novelist Doug Whiteway served brief terms as editors until the arrival in 2007 of Mark Collin Reid, a journalist, editor, and author from Nova Scotia.

Under Reid’s tenure, the magazine’s name changed in 2010 to Canada’s History.

Reid expanded the magazine’s online presence at CanadasHistory.ca and also spearheaded a move into book publishing, producing three national bestsellers, 100 Photos that Changed Canada (2009), 100 Days that Changed Canada (2011), and Canada’s Great War Album (2014).

Since 2007, the magazine has received dozens of national and regional awards and nominations, including a nomination for Magazine of the Year at the National Magazine Awards.

As Canada’s History enters its second century of publishing, its editorial team is focused on increasing the diversity of its stories and storytellers while embracing new media platforms and technologies.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

100 Years with The Beaver

The Editor's Circle was founded in 2020 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Canada’s History-The Beaver magazine. Gifts from patrons and supporters of $500 or more will be recognized annually.

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!