Reframing the North

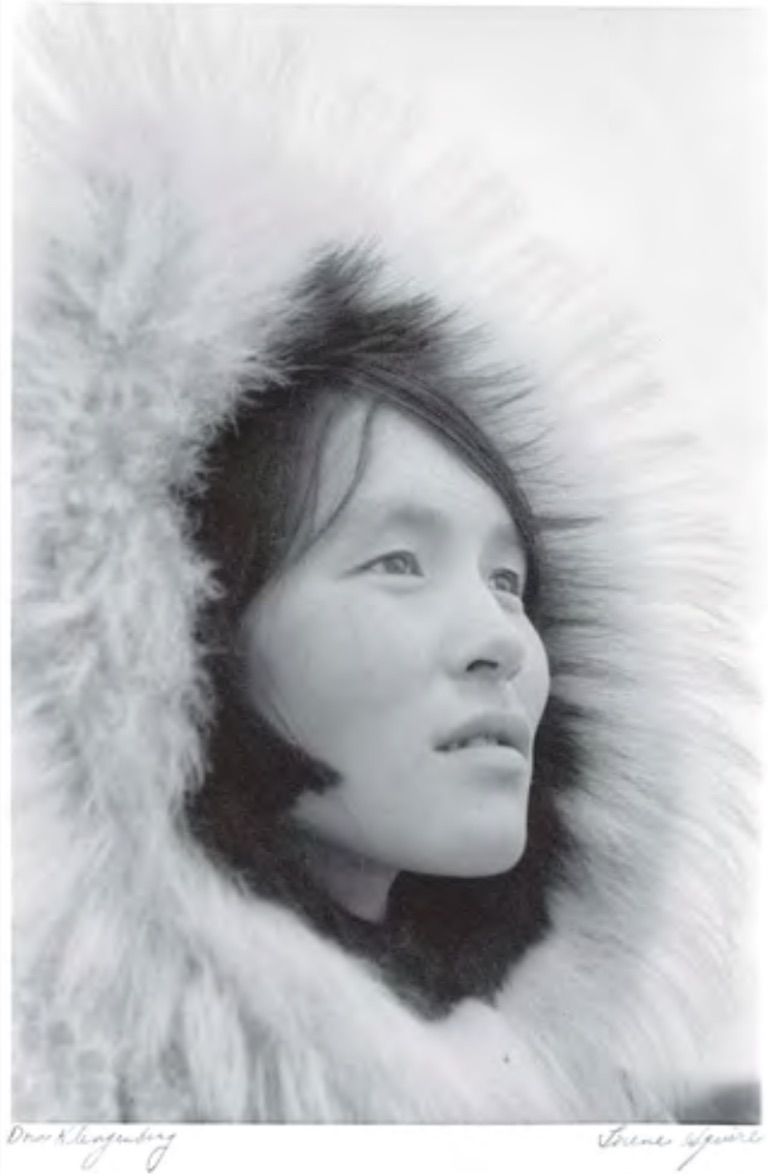

She looks off towards a vista, a horizon, that we cannot see. It’s left outside the frame — a choice of the photographer in making this young woman, and not the changing northern world around her, the sole focus of the camera’s gaze.

Her face framed by a fur-trimmed parka, she is frozen in time.

Among the thousands of images commissioned or collected over the decades by The Beaver magazine, this issue’s cover photo is special for four simple, handwritten words found in the margins of the print: “Dora Klengenberg” and “Lorene Squire.”

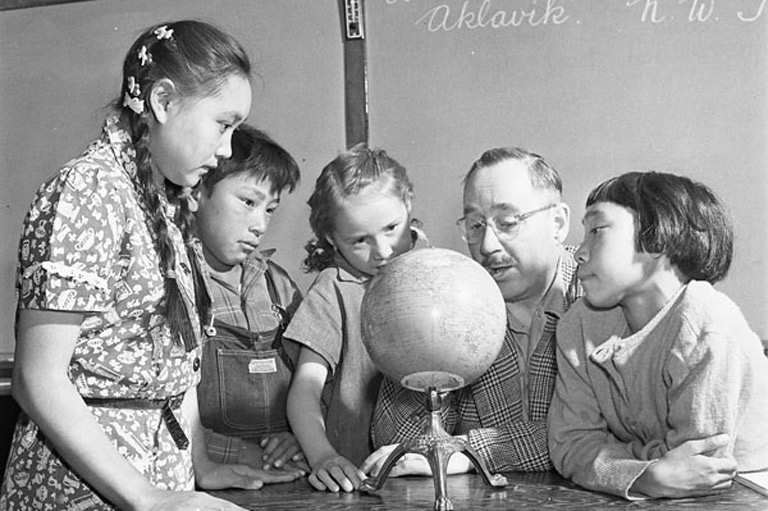

Squire, a photographer, made this photo in 1938 in Aklavik, N.W.T., while on assignment for The Beaver.

This is a rare image — a photo of a woman by a woman — that was created at a time when few female photographers were given opportunities to work alone in Canada’s remote northern wilderness.

The photo is even more special thanks to Squire’s decision to name Klengenberg, who was then the teenaged daughter of a prominent Inuit trader and schooner captain.

Since The Beaver’s debut in 1920, the magazine had rarely named Indigenous peoples in photographs or stories.

As a result, Inuit, First Nations, and Métis peoples were metaphorically pushed to the margins of the magazine — present, yet obscured.

Especially during its first few decades of publication, The Beaver was a magazine that often focused on Indigenous peoples but was unwilling to invite them to share the spotlight.

With this issue, The Beaver, today known as Canada’s History magazine, marks a century of publishing. It was launched one hundred years ago by the Hudson’s Bay Company as part of its 250th-anniversary celebrations.

In its inaugural issue, editor Clifton Thomas wrote of his ambition to make the magazine much more than just an in-house newsletter of the HBC: “If you can inspire us to make a better Beaver, give us your thought. This is a ‘Journal of Progress’ in every sense.”

As the magazine passes the century mark, I find myself increasingly thinking about Thomas’s pledge. Has the magazine lived up to that founding aspiration?

In so many ways, The Beaver has educated and enriched the lives of its readers. Its pages have featured some of the country’s greatest writers and historians, from Pierre Berton and Margaret Mead to Charlotte Gray, Desmond Morton, Lawrence Hill, and countless others. The magazine has helped to connect Canadians to those who lived here before us — celebrating our achievements, mourning our nation’s losses, and offering lessons upon which to draw for the future.

It’s important to understand that the magazine was founded on the premise that it should change with the times. This editorial vision has been reflected in the malleability of its masthead: The “Journal of Progress” became “A Magazine of the North” in September 1933. In 1986, its subtitle changed to “Exploring Canada’s History,” before transforming in 1999 to “Canada’s History Magazine.” In 2010, The Beaver was renamed Canada’s History.

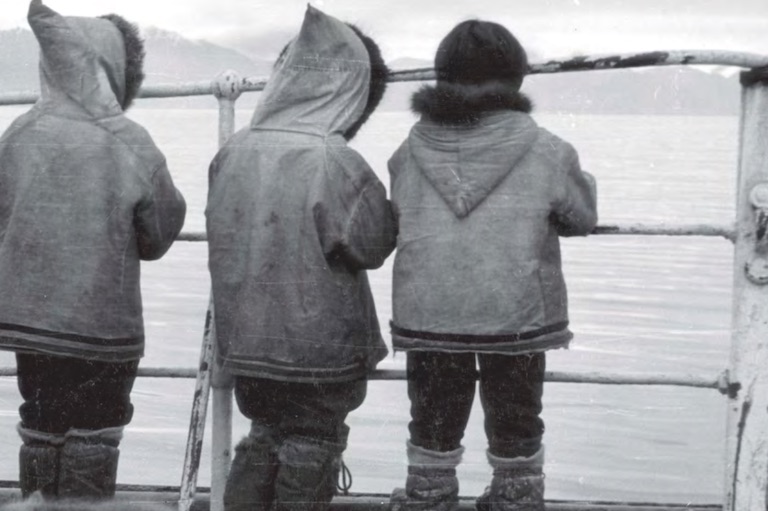

Early issues of The Beaver offered a window on northern ways of life and living that were unfamiliar and even “romantic” to the mostly non-Indigenous readership living in southern Canada. Looking back with one hundred years of hindsight, we realize today that The Beaver’s window was often actually a mirror that reflected non-Indigenous society’s misconceptions about Indigenous peoples.

The North as presented by The Beaver was a wild and rough yet starkly beautiful place filled with resources to exploit and peoples in need of “civilizing.” Prejudice pervaded the early issues of the magazine, with Indigenous peoples often presented in a patronizing light.

As society slowly changed, so did The Beaver. It gradually started to display a greater appreciation for the cultural heritage, ceremonies, and traditions built over millennia by Indigenous peoples. It devoted space to then up-and-coming Indigenous artists such as Harold Cardinal, Carl Ray, and Jackson Beardy while also showcasing artisans and craftspeople such as Salish weavers, Algonquin basket makers, and others.

By the 1970s, the magazine was also beginning to examine Canada’s record of governance in the North, and it searched, tentatively, for solutions to the difficult challenges facing Indigenous communities. This is not to say that the magazine was ahead of its time. It, like society, inched incrementally towards “progress.” That’s why The Beaver’s legacy today remains incredibly complicated.

With this special collector’s issue, we are beginning a new chapter for Canada’s second-oldest still-published magazine. We acknowledge that the magazine has not always been a journal of progress; but it is progressing by finally making room for diverse voices.

In 2017, Canada’s History ran a story on residential schools that likely would not have been published decades ago — at least, it would not have been told from the point of view of the students. In the early pages of The Beaver, residential schools were seen as beacons of civilization in the northern wilderness — keys to the overall scheme of assimilating Indigenous peoples. “Lost Generations,” however, was written by the Inuit writer and poet Mary Carpenter. Her memoir of being taken from her family in 1948 and suffering abuse at a residential school was nominated for a National Magazine Award in 2017.

It has taken many generations, but Canadians everywhere are finally realizing that our neighbours’ stories are our stories, too. We are making room for diverse voices, and we are the stronger for it.

As we consider the legacy of The Beaver, we also look to a future where all Canadians see themselves reflected in the pages of Canada’s History. This special commemorative issue is a crucial step on the journey. Within it, you will find beautiful and compelling images from the Hudson’s Bay House Library Photograph Collection, which holds The Beaver’s enormous photographic legacy and is now part of the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives (HBCA) at the Archives of Manitoba. We are incredibly grateful to the HBCA, and in particular to archivist Bronwen Quarry and Keeper of the Archives Kathleen Epp, for their help as we curated a century’s worth of images for this special issue.

This magazine is divided into themes that explore the cultures and traditions of Indigenous peoples, reveal the historic diversity of wildlife and landscapes in northern Canada, explore the HBC’s influence on the region, and illustrate the profound changes that occurred over time as new technologies and modes of transportation spread across the North. Indigenous writers such as Karine Duhamel and Jennifer Moore Rattray are joined by leading historians and authors from across Canada in providing context for the images that are showcased in the special issue.

We are especially thankful for the HBCA’s work on the Names and Knowledge Initiative — an invaluable project that sees archivists working with Indigenous communities to examine archival images in order to add names and other contextual information.

These archival photos are important in so many ways. They offer glimpses of past ways of living and thinking and help us to reflect on our lives today. For Indigenous peoples, the photos are visual connections with their ancestors, depicting parents and grandparents and other family members and friends.

The images also invite readers to delve deeper into the stories of the people in the pictures, as well as the photographers who created the images. For instance, Dora Klengenberg and Lorene Squire knew each other only for a short time, their lives briefly intersecting before diverging toward separate destinies. I wonder what they talked about in the scant moments they shared? Did they find anything in common?

Photography, by its intimate nature, often creates a special relationship — a momentary closeness — between photographers and their subjects. Did Klengenberg and Squire share their hopes for the future? They were strangers before the photo session — did they consider themselves friends by its end?

One thing we do know: After saying their farewells, the two women never met again. Klengenberg eventually settled at Gjoa Haven, in what’s now Nunavut, where she raised a family. As for Squire, her dreams of a long career in photography were tragically cut short after she was killed in a car crash while on assignment for Life magazine in 1942.

The HBCA’s work is ongoing, and we are asking readers to help. If you recognize anyone in the historical photos presented in this issue, or if you have stories to share about them, contact the HBCA at hbca@gov.mb.ca.

Together, through the Names and Knowledge Initiative, we can work with Indigenous communities to reclaim this important visual legacy and inspire all Canadians to reconsider Canada’s relationships with its Indigenous peoples.

As we reflect on the past, we also want to share our aspirations for the future of Canada’s History. In print and online at CanadasHistory.ca we will continue to work to be a “Journal of Progress” by showcasing new voices and stories that reflect the diversity of this vast country.

It’s been a decade since the magazine was rechristened Canada’s History. As the editor that oversaw the change of names, I’m pleased to announce a return of The Beaver in a new incarnation that honours the past while offering a platform for new voices.

Starting in 2021 we will publish a special annual supplementary edition of The Beaver that will appear within Canada’s History magazine. The special supplement will showcase Indigenous voices, explore new stories, and include new historical research on both the fur-trading era and the North in general.

A century ago, in the inaugural issue of The Beaver, editor Clifton Thomas wrote: “Whether it measures up to this lusty ambition is not for The Beaver to say, but for you, the readers to judge. Thumbs up or down, The Beaver craves your indulgence — to remember that it has not yet found its legs, the first issue being largely an introduction.” After a century of publishing, we believe that this magazine has not only found its legs but aspires to make great strides into the future.

As we mark the magazine’s centennial, I want to thank the Canada’s History team, former staff members, and also current and former members of our board of directors and national advisory council. You have all played key roles in the magazine’s longevity and success.

I also want to express the team’s heartfelt gratitude to you, our readers and subscribers, along with historians, teachers, archivists, and lovers of history everywhere. Without your passion and support, this magazine about the past would literally have no future.

Thanks to you, Canada’s History magazine and the reimagined The Beaver will move forward together, sharing the unique and diverse stories of all Canadians. Here’s to a second century of storytelling!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

100 Years with The Beaver

The Editor's Circle was founded in 2020 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Canada’s History-The Beaver magazine. Gifts from patrons and supporters of $500 or more will be recognized annually.

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!