Difference Makers

Today, we take for granted basic tenets such as racial and gender equality, access to health care, and the rights to education and to safe workplaces free of harassment and undue dangers.

These rights didn’t come freely — they were won by courageous citizens who challenged the status quo in hopes of building a fairer, more just tomorrow.

Here are just a few of the many Canadians who risked reputations, livelihoods, and even their lives to champion a better society for all.

Tomekichi “Tomey” Homma

In early 1900s British Columbia, the right to vote was the domain of a privileged few, and legislation was in place to deny the franchise to both women and non-white citizens.

In 1900, Tomekichi “Tomey” Homma, a Japanese immigrant in British Columbia, decided to challenge the rules that prevented him from voting.

Back then, Canadians were considered naturalized British subjects and as such, Homma contended that gave him the right to vote.

However, British Columbia’s legislation governing provincial elections barred Asian Canadians from the ballot box. Homma sued the provincial registrar, Thomas Cunningham, to force the issue.

During the course of three years, Homma won twice in court, including at the Supreme Court of British Columbia. However, the province continued to appeal.

In 1903, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, England — then Canada’s highest appeals court — ruled in favour of British Columbia, saying provinces have the right to set voting rules for their jurisdictions.

Homma never lived to see Japanese Canadians receive the vote, but his fight inspired others to keep pushing for equal rights. In 2009, the case Cunningham v. Tomey Homma was designated a National Historic Event.

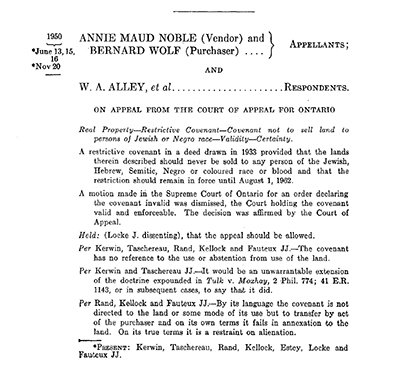

Annie Noble and Bernard Wolf

Today, Canadians would be shocked by rules preventing the sale or purchase of property on the basis of race or religion. However, in the early twentieth century, such provisos had legal weight.

In 1933, Annie Noble attempted to sell a Lake Huron cottage lot in Ontario to a Jewish man, Bernard Wolf. During the process, it was discovered that the original deed had a covenant banning the sale of the property to Jews or to people of African descent.

During a court proceeding to have the covenant quashed, Noble and Wolf cited a then-recent Ontario Court ruling declaring a similar race-based covenant to be illegal.

The manoeuvre failed, and Noble and Wolf lost their case at trial and also at the appeal stage. The case eventually made it to the Supreme Court of Canada, which in 1950 ruled the race-based covenant to be invalid.

Today, the case Noble and Wolf v. Alley is designated a National Historic Event and is considered a key step in the struggle against discrimination in Canada.

The Persons Case

By the 1920s, some Canadian women had won the vote, and others had been voted or appointed to positions long dominated by men, including as Members of Parliament and judges.

Yet, incredibly, women at that time were still not considered “persons” under the law. The issue came to the fore in 1927, when the federal government rejected calls to appoint a woman to the Canadian Senate.

In resisting the pressure, the federal government argued that the British North America Act stated the only “qualified persons” could be senators, and that the act defined a person as a man, not a woman.

In 1927, a group of five prominent women from Alberta — Emily Murphy, Henrietta Muir Edwards, Nellie McClung, Louise McKinney, and Irene Parlby — asked the Supreme Court to rule whether women were legally persons under the BNA Act.

The case, Edwards v. AG Canada, garnered great publicity at the time — and disappointment was widespread after the Supreme Court ruled against the “Famous Five.”

Refusing to quit, the women appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. On October 18, 1929, it ruled in favour of the Famous Five.

Six years later, Cairine Wilson became Canada’s first female senator. In 1997, the Persons Case was designated a National Historic Event.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

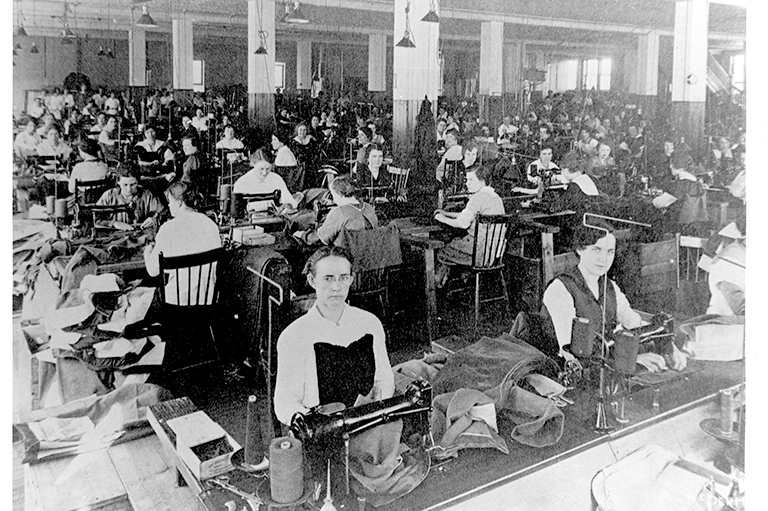

Les Midinettes

They worked up to eighty gruelling hours per week, packed into hot, dimly lit rooms in 1930s Montreal sewing for a mere fifteen cents per dress.

The garment workers, mostly women, came from a broad spectrum of society, including French and English Canadians, Jews, and recent immigrants from Eastern Europe.

Called the midinettes — a contraction of midi and dinette, or “short lunch,” because they flooded by the hundreds into the streets to hurriedly eat their meals and then return to work — the women had no union representation, and no recourse for advocating for better overall conditions or pay.

In 1937, nearly five thousand of the garment workers walked out for better benefits and working conditions.

The strike was remarkable especially because of the co-operation between Roman Catholic francophone employees and their Jewish co-workers; it crossed religious as well as ethnic lines, and was a major step towards greater labour solidarity in the province.

In 2007, the Montreal Dressmakers’ Strike was named a National Historic Event.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

HSMBC @ 100

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!