Monumental Moments

If you drive anywhere in Canada, you will sooner or later encounter one of the thousands of signs indicating buildings, forts, archaeological remains, monuments, battlefields, plaques, and cairns marking places, people, and events of national historic significance. And you may wonder, who decides what is, or isn’t, a part of Canada’s story? Who decides what’s worth preserving?

The simple answer is that those tasks belong to the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (HSMBC) — an appointed body that advises the federal government. Its work is complicated by the reality that everyone wants their story told their way, as well as the fact that there are many stories and perspectives to consider — those of women, men, non-Europeans, Indigenous people, French Canadians, English Canadians, and many more. In addition, there is tension between plans for new development and the desire to preserve old buildings, archaeological digs, and other heritage landscapes.

These issues are not unique to our time. In the late-nineteenth century, when the Dominion of Canada was new and a sense of Canadian identity was starting to form, there was a surge of interest from groups wanting to preserve and to commemorate their heritage.

“Prominent among these groups were provincial historical associations from the Maritimes, Quebec, and Ontario,” wrote historian C.J. Taylor in his history of the HSMBC. “By the beginning of the twentieth century there was considerable concern in these regions over the disappearance of historical remains, particularly forts.”

The story of Fort Chambly, now a National Historic Site, is a revealing example of the extraordinary lengths to which some will go in order to preserve what is important to them. Located near Montreal, where the Richelieu River empties into the St. Lawrence, the fort was established by the French in the seventeenth century. The British military occupied it after 1760. It was briefly taken over by the Americans during the American Revolution and became an important military complex during the War of 1812. But by the 1850s it had outlived its usefulness.

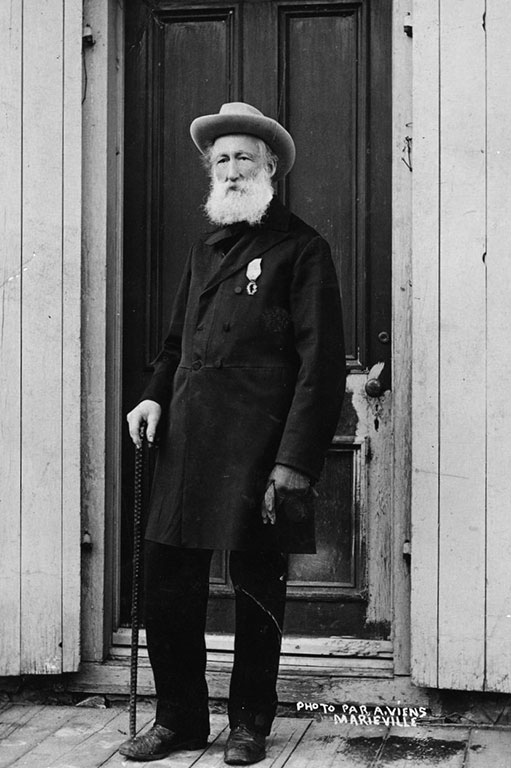

Joseph-Octave Dion was born near the fort’s walls in 1838 and spent many happy days there in his childhood. Dion moved away for a while to pursue his career as a journalist, but when he returned to his hometown in 1866 he was shocked to find his beloved fort in ruins, with local people hauling away stones for construction material.

A Quebec nationalist, Dion deemed it important to preserve the fort’s early French history, not its British past. He proceeded to raise money, organized tours of the fort, created a small museum, and lobbied government.

“Dion, it seems, had assumed total control for the interpretation of the fort’s significance,” noted Taylor in Negotiating the Past: The Making of Canada’s National Historic Parks and Sites (1990). “Dion and his successor, L.J.N. Blanchet, … looked upon their charge as a sacred trust from the French-Canadian past.” A lifelong bachelor, Dion went so far as to live on the site alone for thirty years and died there in 1916 at the age of seventy-seven.

Preserving the ruin was not a priority for the Department of Militia and Defence, which took over management of the fort after the First World War and wanted it demolished. With Dion no longer occupying the site, that might have been the fort’s fate had the HSMBC, created in 1919, not stepped in. Spurred on by its only French-Canadian member, the board designated Fort Chambly a National Historic Site (NHS), one of its first, in 1920 and recommended its preservation. Fort Chambly is now a beautifully restored site where Parks Canada employees dressed in period uniforms of the Carignan-Salières Regiment recreate residents’ day-today lives and interact with visitors.

The HSMBC came about in large part due to the efforts of Parks Commissioner James B. Harkin. The “Father of National Parks” believed that places that preserved history would make better citizens of us all. He envisioned them as “places of resort by Canadian children, who, while gaining the benefit of outdoor recreation, would at the same time have the opportunity to absorb historical knowledge under conditions that could not fail to make them better Canadians.”

Harkin recommended forming an independent body of citizens to advise the Department of the Interior on what was or wasn’t of national historic significance. His vision was realized when the HSMBC was formed in 1919.

While its members were dedicated, educated, and passionate about their work, the board's membership was also typical for its time: white, mostly anglophone, male, elderly, and from eastern Canada.

In a 2006 article in the Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, historian Yves Yvon J. Pelletier described the board as a “Victorian gentleman’s club” whose “recommendations aimed to strengthen the British imperial tradition in the collective memory of Canadians through the repetitive commemoration of the imperial story.”

At the HSMBC’s first meeting, its members decided to organize historic sites into five categories: prehistoric sites, Indigenous forts, French memorials, Loyalist landing places, and landmarks of immigration from the British Isles. As Taylor noted in his history of the board, this approach would influence what was seen as historically significant until the 1950s: “Such a framework provided for a selection of sites that emphasized a particular view of Canada as a British dominion. In this structure, events relating to other ethnic groups and French and native groups after the arrival of the British tended to be ignored.”

Personal areas of interest dominated the early decisions of the board. For instance, Brigadier General Ernest Alexander Cruikshank, an author and amateur historian who served as the board’s first chair, had written a lot about the War of 1812. Consequently, many sites related to that war received historic designations in the 1920s, and the War of 1812 today remains one of the most commemorated events in Canadian history.

Another board member, James H. Coyne, had once written a scholarly article about two Sulpician priests — François Dollier de Casson and René de Brehant de Galinée — who claimed for France the north shore of Lake Erie in 1670. Despite this being a relatively minor historical episode, two places at Port Dover, Ontario, where the two priests set up camp, were among the first three sites to receive official recognition by the board in 1919.

In addition to Cruikshank, Coyne, and Harkin, the first board included Benjamin Sulte, a historian and former military official from Quebec; William Odler Raymond, an archdeacon, historian, and editor from New Brunswick; and William C. Milner, an archivist and journalist from Nova Scotia. The latter became a long-standing irritant in the group’s conflict-filled early years.

Less than a year in, Milner was complaining in a letter to Robert Borden, who had just retired as prime minister, that it was a “hopeless body.” In the letter, Milner alleged that Cruikshank and Harkin were basically amateurs. The letter was forwarded to Prime Minister Arthur Meighen, who ignored it.

By 1923, largely due to Harkin’s lobbying efforts, the cantankerous Nova Scotian was removed from the board. However, Milner continued his criticisms from the sidelines and would haunt the HSMBC for years to come in a controversy involving Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia. Grand-Pré was a key site in the tragedy of Le Grand Dérangement, in which the British expelled about ten thousand French-speaking Acadians between 1755 and 1763. The descendants of Acadians who returned to the area built a memorial church and park at Grand-Pré in the 1920s. The site was dedicated to remembering the expulsion.

However, most of the area’s residents at the time the memorial was created were descended from the New England Planters, English-speaking settlers who came in after the Acadians were removed. They wanted their story told and, spurred on by Milner, lobbied for a memorial at Grand- Pré to something that happened before the expulsion: the deaths of Colonel Arthur Noble and seventy of his soldiers, who were killed in a nighttime attack on a British garrison at Grand-Pré by French and Indigenous forces in 1747. While the board complied in 1924, with plans to install a neutrally worded memorial plaque identifying the site of the attack as a National Historic Event, Milner and his followers felt this was not enough.

“When the text of the HSMBC’s inscription became known, the GPWI [Grand-Pré Women’s Institute] vociferously objected to the board’s neutral portrayal of French and English actions, asserting that it was properly ‘a memorial to a brave officer and his men’ who were ‘massacred’ while protecting an imperial outpost,” Roger Marsters of Dalhousie University wrote in a 2006 edition of Acadiensis. “To view the encounter in any other way was to perpetrate an historical injustice.”

To complicate matters further, Borden, the former prime minister who was born in Grand-Pré and was friendly with Milner, donated an old house to be used as a museum dedicated to Noble and the New England Planters. Clarence Webster, who was appointed to the board in 1923 and was sensitive to Acadian feelings, warned Borden in a letter against adding fuel to the fire: “You must be well aware that Grand- Pré has only bitter memories for the Acadians. They cannot be blamed for being aroused by this fresh irritation. Surely, no step should be taken to fan the embers into a flame of criticism which might cause a repercussion of undesirable magnitude.” In the end, Borden distanced himself from the controversy.

Harkin, for his part, saw that installing the HSMBC’s marker commemorating the 1747 attack at Grand-Pré would cause trouble: “You will observe that we have all the setting for an unfortunate fight,” he wrote to a deputy minister in 1929. “My own opinion is that we should do everything possible to avoid such a fight. I feel that inaction is the better policy.” Thus, the marker commemorating the Battle of Grand-Pré wasn’t placed until 1938. Meanwhile, the Acadian expulsion remained unrecognized by the board.

When asked in 1928 whether the board would acknowledge the Acadian expulsion, Webster replied: “In view of the storm raised over the Noble fight, I believe it will be a long time before the Board will venture to do anything with the matter.” He was right. The expulsion was not designated a National Historic Event until 1955.

Conflicting views over how to portray the various identities of Grand-Pré — Acadian, Planter, and Mi’kmaq — continued over the decades. In 2012, UNESCO seemed to reinforce the Acadian view when it named the “Landscape of Grand-Pré” a World Heritage Site, describing it as an “iconic place of remembrance of the Acadian diaspora.”

Despite its early hiccups — along with inadequate funding and a lack of legislative backing — the HSMBC continued to evolve. Taylor writes that it went through distinct phases, including a period of stagnation in the early 1930s due to the Great Depression. Since putting up cairns and plaques was much cheaper than preserving buildings and landscapes, most of its work involved the former activities.

But an unexpected boon came in form of federally funded relief projects. Unemployed men were sent to places like Fort George, at Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, or Prince of Wales Fort on the shore of Hudson Bay in Manitoba, to do the grunt work of restoring fortifications. The outbreak of the Second World War resulted in a hiatus for the board’s work, but the HSMBC found new energy soon afterward.

“By the 1950s, what you see is a growing interest by local groups in protecting an urban landscape that is disappearing because of industrialization and urban growth,” said Taylor, who retired from Parks Canada a decade ago. “And the board kind of picks up on that, doing inventories and looking at fine old buildings that should be preserved.”

The 1950s was also a significant period in that the board was formally established through the Historic Sites and Monuments Act of 1953. The groundbreaking 1951 Report of the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences, known commonly as the Massey Report, also had an impact. The commission’s cross-Canada sessions heard many complaints about regional imbalance. For instance, while Ontario had 119 National Historic Sites, Saskatchewan had just eight. The Massey Report also noted the preponderance of preserved military forts, which it said “appears to be a curious emphasis in a country that boasts not infrequently of the longest undefended frontier in the world.”

According to Robert Cole of the University of Ottawa, who wrote a 2017 thesis on how the board represented Indigenous history, “the critiques of the Massey Commission greatly influenced the direction of the board. It established committees, appointed more scholars, added a second annual meeting to consider more proposals, and all of these measures contributed to both a greater influx of Indigenous subjects and better reinterpretations of existing Indigenous designations.”

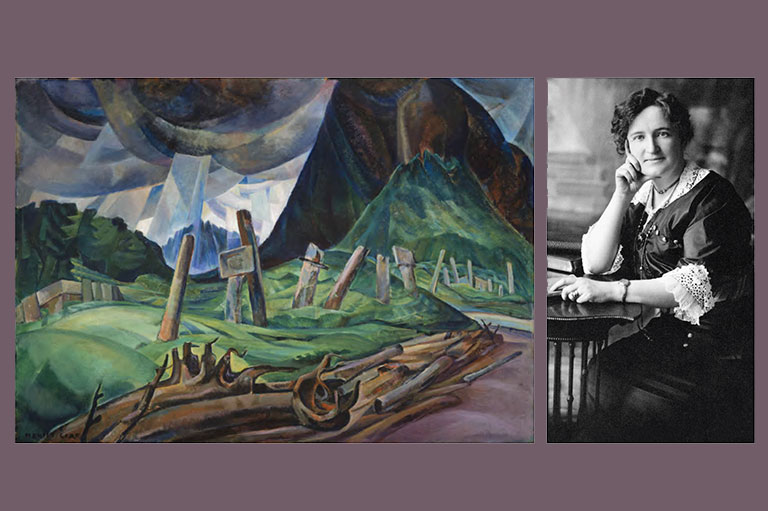

While a few women started to show up in board designations — artist Emily Carr in 1950, suffragist Nellie McClung in 1954, and Emily Murphy, the first woman judge in the Commonwealth, in 1958 — sustained attention to the achievements of women would not begin until the 1980s.

The 1960s saw the dawn of what Taylor calls “the era of the big project.” The federal government directed large sums of money to restoring at least one major historic site in each province. An offshoot of these efforts was the development of an army of researchers, heritage and conservation specialists, curators, and archaeologists working for Parks Canada. The heyday of the big project came to an end in the 1980s, when federal money began to dry up.

Meanwhile, the HSMBC’s mandate was expanded to include the preservation of heritage railway stations in 1989, the gravesites of Canadian prime ministers in 1999, and lighthouses in 2008. Today it lists 970 National Historic Sites, 694 National Historic Persons, 469 National Historic Events, 161 Heritage Railway Stations, and 95 Heritage Lighthouses. Present HSMBC chair Richard Alway said the board has come a long way from when it was first established in 1919: “The understanding of what was important in history when the board was formed — military history, political history, constitutional history — began to change in the 1950s. Social history began to be recognized in various forms. Today it’s easy to see that the discipline of history and the understanding of what is the complete story of our national past has shifted and expanded greatly.”

Alway said the board will soon enter a new era with the addition of three members representing First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people. “We will have within the board authentic voices representing aspects of our past to make sure that we are doing an appropriate and complete job…. We have to make sure we are attentive to shifts in historical understanding and perspectives.” For instance, Fort Témiscamingue in Quebec was first designated in 1931 for its role in French-British rivalry during the early fur trade. Since then, archaeologists have highlighted the site’s importance to the Timiskaming First Nation, and it has been renamed Fort Témiscamingue/Obadjiwan National Historic Site to include the area’s original Algonquin name.

Alway also said the board is reviewing all of its designations with a view to rewriting those that are outdated. Rewritten or not, it can be difficult to describe a site in 640 characters — the amount of text contained in the HSMBC’s distinctive maroon-and-bronze plaques.

Alway believes the plaques remain worthwhile: “The plaque is really meant to be a jumping-off point. The person reading it learns something, becomes interested, and it perhaps causes them to dig more deeply, which they can easily do now with the Internet.”

Preserving the Past

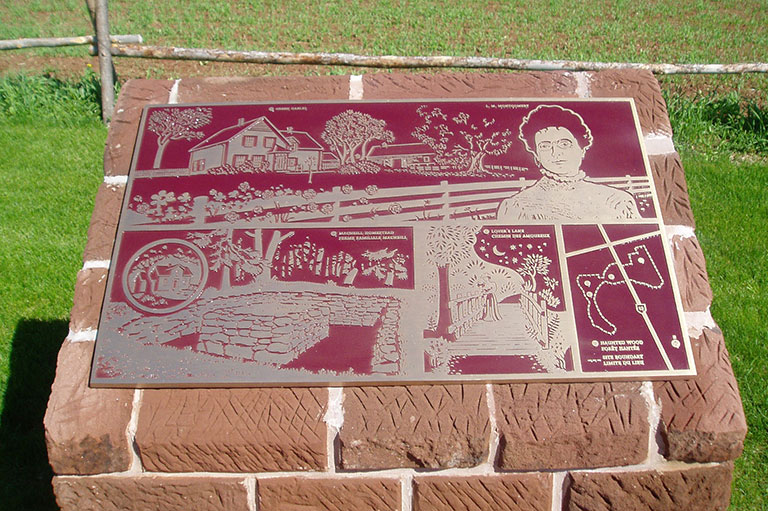

You know of someone or something that deserves to be remembered — but how do you go about nominating it for official commemoration? The nomination process for significant people, places, or events is relatively straightforward. The HSMBC secretariat receives an average of seventy nominations per year, with most submissions coming from the public. The board judges the nominations against a set of criteria and guidelines.

To be considered, “a place, person or event must have had a nationally significant impact on Canadian history, or must illustrate a nationally important aspect of Canadian human history.” Buildings and sites must be at least four decades old to be considered for designation. For historically significant people, they must have been deceased for at least twenty-five years to qualify. Exceptions are made only for prime ministers. For events, they must be at least forty years old and should represent a “defining” experience in Canadian history. Final decisions are made by the minister responsible for Parks Canada, at the recommendation of the board.

For more go to Parks Canada’s page National program of historical commemoration.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

HSMBC @ 100

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!