Remarkable Women

It’s a well-known fact that women have often been bypassed by traditional history, especially in the fields of science and health care. And yet, women have shown great innovation in these fields.

The National Historic Sites and Monuments Board has commemorated many women who have contributed to great scientific and medical advancements in Canada.

We can’t list them all, but here are just a few of these remarkable women.

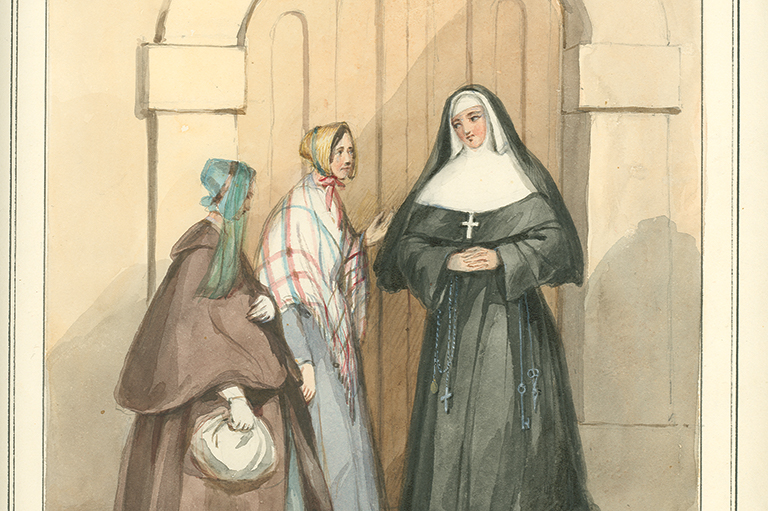

Les Sœurs de Miséricorde

The Sisters of Mercy is a Catholic order created in Dublin, Ireland, in 1831 to address the increasing number of children being born out of wedlock during the Industrial Revolution and consequent urbanization.

In 1848, Montreal bishop Ignace Bourget asked a widow, Marie-Rosalie Cadron (born Jetté), to create l’Institut des Soeurs de Miséricorde in Lower Canada. Cadron had already created an establishment with a similar mission a few years before.

Up to 1865, its members were the only nuns to practise as certified midwives in Canada. They also supported the development of obstetrics and pediatrics, mostly in French-speaking communities.

The sisters imposed a strict discipline on their charges, and the unwed mothers under their care had to follow a stern regime of contrition and penitence for breaking one of the great social and religious taboos of the era.

Starting with the Hôpital Général de la Miséricorde in Montreal, the sisters established a network of hospitals, nursing schools, and orphanages. By 1900 they had establishments in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Wisconsin.

In Montreal, two hundred nuns worked at two hospitals caring for mothers and their children. The Sisters of Mercy still operate modern-style care facilities for mothers and their children in Canada, Africa, and Latin America.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Les Sœurs de la Charité de Montréal (Sœurs Grises)

In 1737, a young widow, Marguerite d’Youville, dedicated herself to charity and, with a few other women, created a secular organization in Montreal to help the poor, the sick, and the orphaned.

Their order was known as “Les Soeurs de la Charité.” In 1747, d’Youville was asked to assume the operation of the Hôpital général de Montréal, a hospital founded by merchant François Charon that had, after his death, been poorly managed by his brothers.

With the hospital nearly bankrupt, d’Youville and her colleagues opened the facility to women and men as well as to the poor and those with physical and mental disabilities.

The changes angered some in the community, who mockingly called the Sisters of Charity “Grey Nuns.” (Grey was a French colloquialism for drunk, and the name was a not-so-veiled jab at d’Youville’s deceased husband, a former alcohol trader.)

The sisters persevered, and, in 1755, the order was officially acknowledged as a religious community by the Roman Catholic Church. D’Youville and her followers donned grey uniforms and proudly kept the Grey Nuns moniker.

After d’Youville’s death in 1770, the Grey Nuns expanded beyond Quebec, opening hospitals and schools elsewhere in Canada, as well as in the United States, Latin America and Africa.

The Grey Nuns was the first organization to devote itself to the whole range of social work — from hospitals to schools, to orphanages, to missionary work, taking care of the poor, the disabled, and the elderly.

D’Youville was also the first woman in Canada to create a religious community and the first person born in Canada to be canonized.

Jeanne Mance

Born in Langres, France, in 1606, Jeanne Mance was a devout Catholic who involved herself in charity work. In 1641 she joined the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, an association dedicated to the creation of a Catholic colony in Canada.

Financially supported by a rich widow, Madame de Bullion, she sailed for New France in 1642 with French military officer Paul de Chomeday, Sieur de Maisonneuve, and about 150 settlers.

They founded Ville-Marie on the island of Montreal during a period of intense conflict with the Six Nations Confederacy, whose homeland was being colonized by the French.

In Montreal, Mance cared for the sick and the wounded and became the first lay nurse in Canada, founding the Hotel-Dieu, Montreal’s first hospital.

Yet Mance’s contributions to Montreal went far beyond providing health care. In 1650, she convinced Maisonneuve to return to France to recruit new settlers, 177 of whom arrived in 1653 — an act that essentially saved the dwindling colony (only 50 people were left of the original 150).

In 1658, Mance herself went back to France and recruited les Religieuses Hospitalières de Saint-Joseph, a religious order devoted to the care of the sick, to work at her hospital.

She died in Montreal in 1673, still directing the Hôtel-Dieu. In 2012, Mance was officially acknowledged by Montreal’s city council as a co-founder of the city, along with Maisonneuve.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Irma LeVasseur

Born in 1877 in Quebec City to a family of artists, Irma LeVasseur saw her two younger brothers die in infancy, which was a common occurrence at a time when one child out of four did not live past a year.

The tragedies spurred her toward a career as a doctor — but at the time Canadian universities refused to accept women into their medical schools.

Undaunted, LeVasseur moved to Minnesota, where in six years she completed her medical training, specializing in pediatrics.

In 1900, LeVasseur returned to Québec but was refused a medical licence. It would take another three years — and the passing of a private member’s bill at the provincial legislature — before she was finally certified by Quebec’s college of physicians and surgeons.

During the delay, she practised in the United States, and following her certification in Quebec, LeVasseur travelled to Europe for further studies. Returning in 1908, she helped to found Montreal’s Hôpital Ste-Justine for children.

At the outbreak of the First World War, LeVasseur headed overseas to treat Allied troops, and in 1915 she journeyed to Serbia, where she cared for thousands of soldiers.

In 1922, she founded the Hôpital de l’Enfant-Jésus in Quebec City; she founded a clinic for children in 1927, and, later, a nursing school.

Sadly, her accomplishments were largely forgotten, and she died in 1964 in relative obscurity. Today, however, LeVasseur’s recognized as a champion for women in the medical profession and for children’s health and welfare.

Margaret Newton

Plant pathologist Margaret Newton is today remembered for her research into wheat stem rust, a fungus that devastated Canadian wheat crops in the early twentieth century.

Born in Montreal in 1887, Newton attended McGill University, where in 1917 she worked on the first scientific study of wheat stem rust in Canada. At the time, very little was known about this fungus, which had reached epidemic levels.

Thanks to Newton’s research, new rust-resistant strains of wheat were created, saving Canadian farmers millions of dollars worth of lost crops.

In 1922, Newton became the first Canadian woman to earn a PhD in agriculture. She was also one of the first women in Canada to embark on a lifelong career in scientific research, at a time when women everywhere were fighting for acceptance and striving for greater equality in the sciences.

By 1945, when she retired as senior plant pathologist at the Dominion Rust Research Laboratory in Winnipeg, her groundbreaking work had attracted the attention of scientists from grain-growing countries around the world.

Newton’s early retirement was prompted in part by respiratory problems that were likely caused by her extensive exposure to stem rust spores. She died in 1971.

Carrie Matilda Derick

Born in Clarenceville, Quebec, in 1862, Carrie Matilda Derick took the unusual step, for a woman at the time, of pursuing studies in biology after obtaining her teaching licence for l’École normale de Montréal.

She went on to study at McGill University, at Harvard, at the Royal College of Science in London, England, and at the University of Bonn in Germany.

In 1891 she became the first woman to achieve a staff teaching position at McGill University, working as a demonstrator. She became a lecturer of comparative morphology and genetics, then an assistant professor.

In that position Derick created a course called “Evolution and Genetics,” which made her a pioneer; at the time, evolution was still controversial, and genetics was a completely new field of study.

Derick published many peer-reviewed articles in the field of botany and earned respect among scientists around the world as well as a mention in the American Men of Science, published in 1910.

She was named professor emeritus in 1929, just before leaving McGill for reasons of health.

In addition to her demanding career as a scientist and a teacher, Derick also immersed herself in various social causes.

She promoted women’s suffrage and became a member of organizations such as the Local Council of Women in Montreal, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Council of Education, the Federation of University Women of Canada, the Montreal Folklore Society, and many others. Derick died in 1941.

Maude Elizabeth Seymour Abbott

Maude Elizabeth Seymour Abbott had a rough start in life: Her father left home for the United States right after her birth in 1868, and her mother died of tuberculosis the following year.

Maude and her sister Frances were subsequently raised by their maternal grandmother.

Abbott was a good student, and in 1885 she earned a scholarship to McGill University. She graduated in 1890 with a bachelor of arts degree and hoped to attend McGill’s medical school, but the university barred women from the faculty.

Instead, she attended Bishop’s University in Sherbrooke, Quebec, graduating with a medical degree in 1894.

After three years of further study in Europe, Abbott returned to Montreal, where she opened a health clinic for women and children. It was at this time that she began studying heart disease, especially in newborns.

In 1898, she became curator of the McGill Medical Museum and in the early 1900s, she published the first articles written by a woman in the Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology of Great Britain.

By this time, Abbott was a world-renowned expert regarding heart defects in children. In 1910, McGill awarded her an honorary degree in medicine and appointed her as a lecturer in pathology — despite maintaining its men-only medical school.

During her long and diverse career, Abbott published more than 140 articles on topics ranging from heart diseases to the history of medicine, including the important 1936 monograph Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease.

In 1940, she suffered a stroke. A few months after her death, Paul Dudley White, an eminent American cardiologist, called Abbott “the world authority on congenital heart diseases.”

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

HSMBC @ 100

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!