After the Pandemic

In the early twentieth century, an infectious disease known as “the strangler” killed thousands of Canadian children every year. Coating the throats of its victims in a thick, sticky film, this respiratory illness spread in families and among crowds, often transmitted by people who themselves experienced only mild symptoms.

An antitoxin existed to treat the disease, but no facility in Canada was equipped to produce it. This maddening gap — a treatment theoretically available yet practically and affordably out of reach — galvanized a crusading doctor to establish a production facility in Toronto to ensure a domestic supply for Canadian citizens.

That disease was diphtheria.

Now, a century later, Canada finds itself battling another deadly public-health threat: the COVID-19 pandemic. How will it end? Will we ever return to normal? It has been a surreal, frightening, and transformative experience.

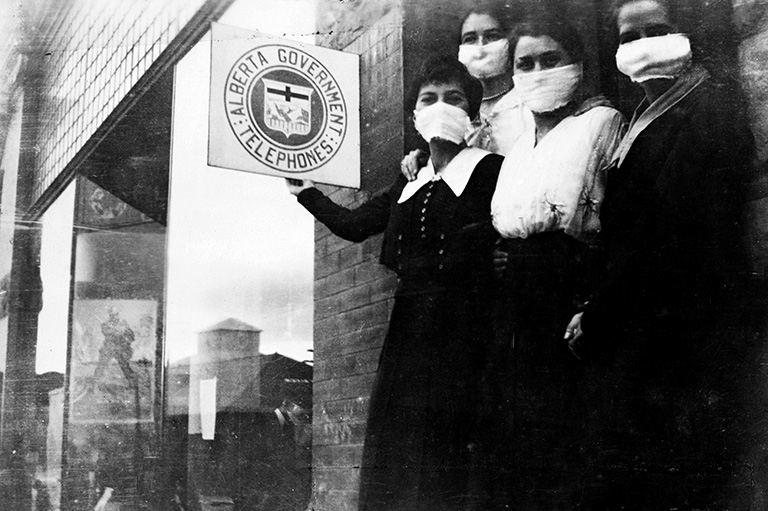

Yet, while it may seem as though we’re living through a completely unique situation, Canadians and people around the world have withstood pandemics and epidemics in the past. Some, like the great influenza pandemic of 1918–20, sparked personal or political divisions over wearing a mask, while others, like Ontario’s smallpox epidemic of 1919, involved sharp debates over getting vaccinated. Others, like the polio epidemics of the mid-twentieth century, showed the importance of political leadership in creating a strong unity of common purpose against infectious disease threats.

Much can be learned from each of these moments in time. They can help us to understand our current COVID-19 experience and offer insights into how the pandemic may change the shape of our society in the future.

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

CLOSED BORDERS AND QUARANTINES

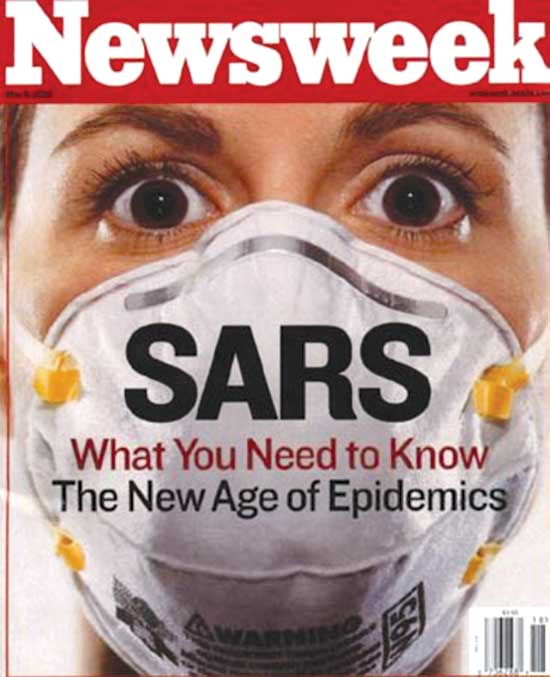

News about a new disease that we today know as COVID-19 began to emerge on December 31, 2019, with international media reporting cases of a deadly new respiratory virus in Wuhan, China. To Canadians familiar with the SARS epidemic that unfolded in 2003, the stories emerging from China sounded familiar and alarming.

SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) first emerged in China in November 2002. It spread quietly for months — mainly in hospitals and among health-care workers — before Chinese authorities notified the World Health Organization about the outbreak on February 10, 2003. By this time, 305 people had fallen ill, a third of whom were nurses or doctors, and five people had died.

One case, involving an infected person who stayed at a hotel in Hong Kong, caused SARS to spread in several directions, including into Canada. A Canadian woman who stayed at the hotel in question contracted SARS though a chance encounter. Unaware of her infection, she returned to Toronto, where she passed on the virus to her son. The woman died at home on March 5, 2003. Meanwhile, her son went to Scarborough Grace Hospital for treatment, sparking a chain of infection among hospital staff.

Fearful of the virus spreading beyond hospitals, Toronto Public Health activated its emergency plan, which among other things called for quarantines of patients with suspicious symptoms as well as their close contacts. It was the first such quarantine order declared in the city in more than fifty years. As Toronto’s medical officer of health, Dr. Sheela Basrur, put it, “With this new bug that we couldn’t test for, couldn’t treat, and couldn’t prevent, there was not much else we could do.”

By the end of the SARS epidemic, there had been more than 8,400 reported cases and at least 774 deaths globally, including 251 cases and 44 deaths in Canada, mainly in Toronto.

Before vaccines brought infectious diseases such as diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), and polio under control, quarantines were fairly common. Those who were quarantined stayed in their homes for a set period of time (depending on the disease) to prevent further spread. If they became ill, they were isolated in hospital. The SARS outbreak in Toronto resurrected the issue of quarantine and also highlighted the weakened state of communicable-disease control in Canada at all levels in 2003, prompting major investigations of the public health system both in Ontario and at the federal level. As a result, the Public Health Agency of Canada was established in 2006, and the federal Quarantine Act was strengthened in an effort to prevent the importation of disease threats.

Yet these measures, taken more than a decade ago, did not prevent SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes the disease known as COVID-19) from rampaging through Canada starting in early 2020.

In January 2020, Canada’s chief medical officer of health, Dr. Theresa Tam, saw the new virus outbreak in China as another possible SARS. However, the reports out of China didn’t cause a strong reaction on her part, since she thought the virus was not infecting health-care workers, as SARS had. In reality, the Chinese government had initially attempted to suppress news of the virus, disciplining the doctors who tried to sound warnings about it.

On January 20, the first case in the United States was announced. That day, Tam, who heads the Public Health Agency of Canada, reassured Canadians that the risk posed by the new virus was low: “I don’t think there’s reason for us to panic or be overly concerned,” she tweeted. U.S. President Donald Trump also downplayed the threat, ignoring warnings in intelligence reports regarding the virus’s potential of becoming a pandemic. On the very same day, by way of contrast, South Korea reported its first case and immediately mobilized vast resources for testing, screening, and quarantines.

Events moved quickly, as did the virus, including beyond China. The virus turned out to be easily spread between people, transmitting efficiently before symptoms appeared. By January 23, the Chinese government had ordered a strict lockdown of the city of Wuhan, which seemed incredible, as did the isolation hospitals that were erected to house the rapidly rising number of infected people. In Canada, the first lab-confirmed case came on January 27.

In early February, several cruise ships were quarantined after the virus spread among passengers and crews. The first afflicted ship, the Diamond Princess, entered into quarantine on February 5 while docked at Yokohama, Japan. By the end of the quarantine four weeks later, there had been seven hundred cases and fourteen deaths on board the vessel. These ocean liner outbreaks highlighted the severity of the virus, especially in crowded, semi-enclosed areas. They prompted several countries, including Canada, to deploy special flights to evacuate citizens back to their home countries. Canadian citizens rescued in the airlifts were placed into quarantine. Soon afterwards, the global ocean-cruise industry was thrown into a suspension from which is has not yet recovered. It was becoming very clear that this new virus was much more easily spread than SARS, if perhaps less deadly as a proportion of cases.

On February 12 the novel virus was given its name, SARS-CoV-2, which means “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.” The disease it causes was labelled “coronavirus disease 2019,” or simply COVID-19. At the time, many Canadians and Americans felt somehow immune to what was happening in China.

In the United States, Trump declared on February 27 that the virus “like a miracle” would disappear, despite top-secret briefings that informed him otherwise. In Canada, Tam and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau both resisted calls to close the country’s borders to foreign travel from afflicted areas, despite moves by Australia, New Zealand, and the United States to do just that. In a press briefing on March 5, Tam said sealing off borders was not an effective approach to containing the virus, and Trudeau warned against “knee-jerk reactions.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Nevertheless, the virus’s rapid spread in Italy and New York City during February and March raised alarms. On February 26 Canada’s health minister advised people to stockpile food and medication. Bathroom tissue quickly became the most hoarded item across North America, prompting Ontario Premier Doug Ford to remark: “I still can’t get my head around this toilet paper situation.” By early March 2020, when COVID-19 forced an unprecedented national lockdown in Italy, the worldwide threat was obvious. On March 11 the World Health Organization finally made it official: The planet was in a pandemic.

What might the world, and Canada, be like today if governments and health authorities around the globe had applied the lessons from SARS to the current outbreak? Allowing SARS to spread quietly for several months in 2002–3 before alerting the world to the threat helped to ensure its unchecked spread beyond China to Canada and several other countries. Did history repeat itself during the beginning of the current pandemic? Will future virus outbreaks be met with swift and decisive global action to stop them in their tracks? Only time will tell.

LIVES AND LIVELIHOODS UNDER LOCKDOWN

The reality of the pandemic hit home for many North Americans when the National Basketball Association suspended its season on March 11, 2020, after a player from the Utah Jazz tested positive for COVID-19. On March 12, Prime Minister Trudeau’s wife, Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, tested positive for COVID-19, forcing their family into quarantine and causing the prime minister to manage the rapidly growing crisis from his home. By late March, all provinces and territories were under states of emergency, prompting varying degrees of school closures, prohibitions against gatherings, the closing of non-essential businesses, restrictions at borders, and self-isolation for returning travellers.

By March 15 there had been 338 cases and one death due to COVID-19 in Canada; by April 23 total COVID-19 cases in Canada hit 42,110, and 2,147 people had died, surpassing the 2,000 Canadians who died during the 1957–58 influenza pandemic, which claimed some four million lives worldwide. By April 12, approximately four billion people, more than half of the earth’s population, were in some form of lockdown, an unprecedented global experience.

With COVID-19 cases and deaths rising rapidly in the spring of 2020, fear grew that this pandemic might rival the deadly “Spanish flu” pandemic of 1918–20 — an outbreak that infected at least five hundred million people (a third of the world’s population at that time) and left some fifty million dead, including fifty-five thousand Canadians. Yet there are several important differences between, on one hand, the 1918–20 pandemic experience in Canada and its aftermath and, on the other, how the COVID-19 pandemic has so far played out.

In the last months of the First World War, influenza spread around the world relatively slowly on steamships, exacerbated by the movement of troops. It moved across Canada primarily by railway, sparking short-lived, acute, localized epidemics, before passing on. In Canada, the worst of the second wave of the influenza pandemic lasted from early September through late November 1918, and severe outbreaks rarely struck the same area twice.

Lockdowns were limited, locally applied, and focused on restricting public gatherings to enable physical distancing. Business closures were limited and were mostly the result of sick staff. The National Hockey League continued playing through the thick of the pandemic and only cancelled the final game of the Stanley Cup playoffs in April 1919 when five players and the general manager of the Montreal Canadiens landed in hospital with the flu. (Defenceman Joe Hall died less than a week later.)

The 1918–20 influenza pandemic altered the lives of those who were directly affected. Since young adults were its primary victims — including returning soldiers and family breadwinners — it threatened the economic security of families in an era without any government safety nets. However, its broader socio-economic consequences were dampened by other major epidemics and deadly health threats that persisted during the late 1910s and into the 1920s, such as smallpox, diphtheria, and pertussis. Although the 1918–20 pandemic led to advances in medical research, planning, and international cooperation — as well as the establishment of a federal Department of Health in May 1919 — on the social and economic level, not much actually changed in the pandemic’s aftermath.

Today’s pandemic has been much more of a shared global event. It has affected large regions in successive waves that have often lasted for months and then recurred. The broad public-health measures, travel bans, and unprecedented lockdowns, implemented and re-implemented over extended periods, have caused much wider and deeper economic effects than was the case after 1918.

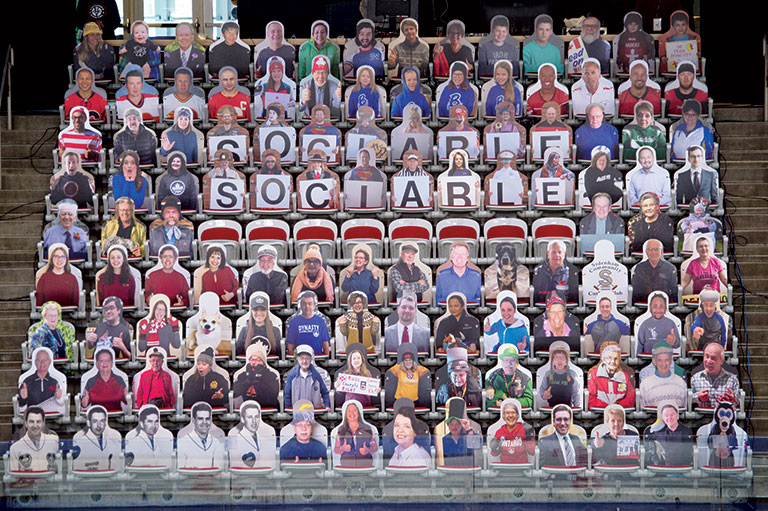

COVID-19 has overturned entire industries and shaken the worlds of professional sports and the arts. The Canadian Football League cancelled its 2020 season. The National Hockey League suspended operations in March 2020, later resuming play in “bubbles,” with players sequestered in hotels and fans barred from arenas. Sports leagues in other countries made similar pivots. Meanwhile, around the globe, auditoriums fell silent, galleries and museums were shuttered, and movie theatres went dark as public gatherings and events were either severely restricted or banned altogether.

In Canada, federal and provincial economic supports have provided lifelines to businesses and have relieved immediate financial anxieties for many individuals, but they haven’t prevented the social and economic fallout of lockdowns. In January 2021, the Canadian Federation of Independent Business estimated that the pandemic could force between 71,000 and 222,000 Canadian businesses to close permanently. In terms of its economic impact, the COVID-19 pandemic has no precedent in Canadian medical history. The ongoing financial hardships caused by COVID-19 have sparked debate over whether Canada should, going forward, provide all Canadians a basic living wage. Indeed, in February 2021, a Liberal Member of Parliament introduced Bill C273, a private member’s bill calling for the establishment of a guaranteed basic income for all Canadians. In the wake of COVID-19, will Canada decide to widen its social safety net?

MEDICINE AND MANUFACTURING

As the COVID-19 pandemic worsened in the spring and early summer of 2020, the number of severely ill patients needing ventilators to assist their breathing escalated. Yet ventilators were in short supply, spurring efforts to manufacture them and to deliver them to where they were most needed. A similar need for specialized medical equipment complicated the fight against polio in the early to mid-twentieth century.

Waves of polio epidemics hit Canada from the late 1920s through to the 1950s. This devastating disease, known colloquially as “the crippler,” is similar to COVID-19 in that cases can vary in severity from mild to deadly. The polio virus weakens or paralyzes various muscles, including those around the lungs, thereby impairing its victims’ ability to breathe.

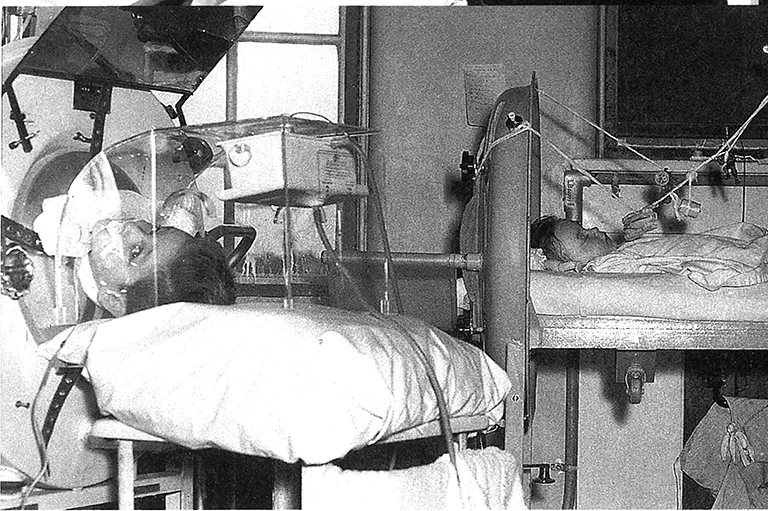

In polio’s worst cases, the iron lung, a ventilation machine that uses negative pressure to help patients breathe, was an essential technology. However, iron lungs were often in short supply, since many patients required breathing support for months, years, or even decades. In 1937, at the height of a polio epidemic in Ontario that claimed 199 lives, twenty-seven iron lungs were hurriedly assembled in the basement of Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children.

In the polio crisis of 1953 — a national emergency during which nine thousand people contracted polio and five hundred died — the Royal Canadian Air Force rushed iron lungs around the country. Ground zero of the 1953 epidemic was Winnipeg, where at the peak of the crisis ninety-two polio patients were dependent on iron lungs at the city’s King George Hospital.

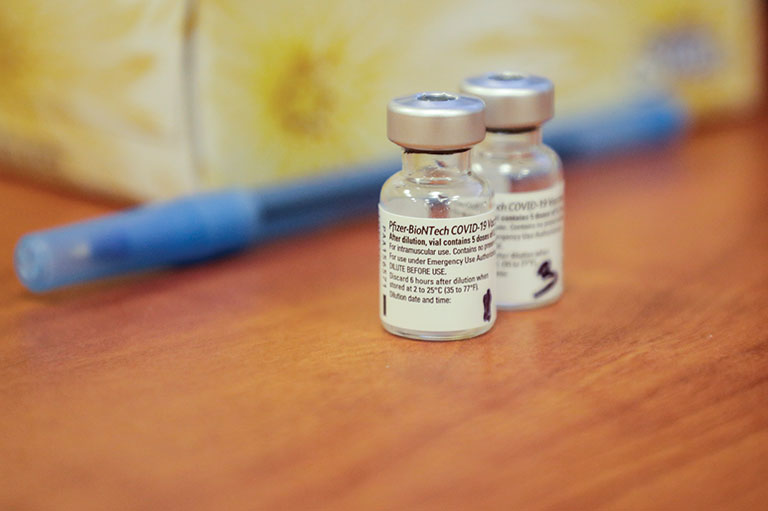

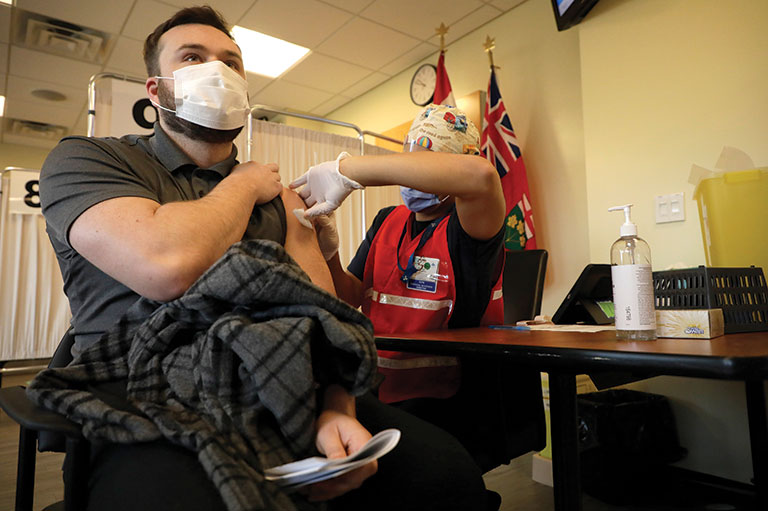

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed Canada’s dependence on foreign manufacturers, not only for necessary medical equipment like ventilators and N-95 masks but also for life-saving vaccines. Canada approved two vaccines, one produced by Pfizer and BioNTech and the other by Moderna, in December 2020, and limited vaccinations of the most vulnerable groups, especially residents of long-term care homes, began almost immediately. However, in these early stages of the vaccination effort, Canada experienced unexpected delays in receiving promised shipments of vaccines. Meanwhile, the United States was vaccinating its citizens at a rate of more than one million per day by February 2021, rising to more than two million per day in March. As Canada lagged far behind the United States and the United Kingdom in its immunization program, Canadians demanded to know why COVID-19 vaccines were not being produced here at home. A similar lack of domestic production capacity hampered Canada’s efforts to treat diphtheria in the early twentieth century.

In Ontario alone, diphtheria killed thirty-six thousand children between 1880 and 1929. In 1924, a peak of nine thousand diphtheria deaths occurred across Canada. An antitoxin to treat the disease had been discovered in 1890, but Canada had to import the medication from the United States at a price beyond the means of many families with children, who were most vulnerable to the disease.

In response to this situation, the Antitoxin Laboratory (later Connaught Laboratories) was established in 1914 as a self-supporting, public-service-based part of the University of Toronto. The new biologicals research and production facility was tasked with preparing a provincial — and, soon afterwards, national — supply of diphtheria antitoxin as well as other essential biological public-health products, such as smallpox vaccine.

In the summer of 1924, Dr. John G. FitzGerald, founder of Connaught Laboratories, visited the Pasteur Institute in Paris, where he met with Gaston Ramon, who had recently discovered a new method to control diphtheria, called diphtheria toxoid. Similar to a vaccine, it seemed to prevent diphtheria. However, Ramon was not yet able to show how effective the toxoid could be beyond his lab. Confident that Connaught could produce the toxoid, FitzGerald conducted several field trials to put it to the test.

One of the most significant trials took place in Hamilton in 1925. In 1922, there had been 742 cases and 32 deaths due to diphtheria in Hamilton. By 1927, after the introduction of the toxoid treatment, the number of cases fell to 368, with 18 deaths. The downward trend continued: In 1931, there were only five cases and no deaths. The following year, a public-health exhibit proclaimed: “Hamilton Slays a Dragon.” A subsequent trial in Toronto demonstrated that three doses of toxoid reduced diphtheria incidence by ninety per cent among children. This Canadian work preceded efforts in the United States, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere to utilize the toxoid to bring diphtheria under control. Diphtheria toxoid was the first modern vaccine and ushered in a new era of effective prevention of formerly devastating pediatric infectious diseases.

What happened to Connaught Laboratories, which had played such an essential role in the development and production of the diphtheria toxoid and — as we will see later — polio vaccines? Connaught was sold by the University of Toronto in 1972 and privatized. Following several subsequent acquisitions and mergers, Connaught’s legacy is today part of Sanofi, which is based in France. Its subsidiary Sanofi Pasteur has been developing a COVID-19 vaccine in collaboration with GlaxoSmithKline, but the Sanofi Pasteur Toronto site — which develops and produces other vaccines and biologicals — has not been directly involved.

However, amid the pandemic’s third wave in March, 2021, the federal and provincial governments, and Sanofi Pasteur Ltd., announced a joint $925-million investment to build an influenza vaccine manufacturing facility in Toronto.

As well, the federal government is funding the construction of a new $126-million vaccine manufacturing facility in Montreal. With a goal to complete construction in July 2021, the new facility will cost an additional $20 million per year to operate. “When it comes to the next pandemic flu we should be self-sufficient,” said federal Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry François-Philippe Champagne. “If there’s one lesson learned from the current COVID pandemic it is that we need to have a strong Canadian biomanufacturing sector.”

POLITICS AND PUBLIC HEALTH

Political leadership, or the lack of it, can greatly impact a society’s efforts to fight pandemics. Politics played a critical positive role in ultimately bringing the polio-epidemic era to an end, thanks in large measure to the efforts of an American president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and a Canadian health minister, Paul Martin Sr., each of whom was afflicted with the disease.

Roosevelt was diagnosed with polio in 1921. Shortly after he became president in 1933, Roosevelt’s polio experience inspired the establishment of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. The organization’s annual March of Dimes fundraising campaigns to support polio treatment and poliovirus research helped to expedite the development of polio vaccines. As for Paul Martin Sr., he contracted polio as a child in 1907, as did his son (and future prime minister) Paul Martin Jr. in 1946. Spurred on by his experience with polio, Martin Sr. expanded support for public-health research that, when coupled with American funding and research, made possible several key Canadian contributions to the development of the first polio vaccine.

By way of contrast, recent U.S. President Trump publicly downplayed the pandemic from its first emergence in China, despite being made aware of its potential to become a devastating pandemic. He promoted questionable treatments, even suggesting at a press conference in April 2020 that injecting disinfectant might fight the virus in the body. Although Trump later claimed that he was being sarcastic, many of his supporters took his comment seriously, leading some to inadvertently poison themselves. Trump also questioned the importance of mask wearing and physical distancing. Even after Trump himself contracted COVID-19, his counterproductive public-health views and behaviour barely changed. His views and actions — or lack of actions — and their acceptance from his political supporters undoubtedly furthered the spread of the virus and added to its unprecedented U.S. death toll. By the one-year anniversary of the declaration of the pandemic, more than half a million Americans had died of COVID-19.

Public-health politics have defined the COVID-19 pandemic in several ways. In the absence of effective treatments and vaccines, personal strategies, such as handwashing, physical distancing, and wearing masks, provided the only protection for individuals and for communities. Such strategies, especially the enforcement of mask wearing, became politicized during the pandemic, as they did in some cities during the 1918–20 influenza pandemic.

During polio epidemics, the most divisive issue was whether or not school openings should be delayed, because case counts usually rose in the summer and into the fall, when schools normally opened. Were children safer at school under supervision or if left less watched at home or on the streets? The answer varied and was decided locally. The school-closing issue during the COVID-19 pandemic has been further complicated by the challenges of remote learning and its management by parents, many of whom have also been forced to work from home.

Polio patients, mostly children, were often isolated in hospitals specially designated for longer-term treatment, particularly if they were dependent on iron lungs, with visitor contact very limited. For COVID-19 patients in hospitals and long-term care homes, such isolation has been even more strictly enforced. In many cases no visitors were allowed, and many patients died alone, except for tenuous virtual connections to family.

Subsequent probes into poor conditions at some long-term care homes have sparked demands for reforms to elder care across Canada. Will nursing homes be placed under tighter government control and held to higher standards of care?

At the same time, medical professionals are reporting high levels of COVID-19-related burnout. An aging population will require a robust support system of doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals. But will COVID-19 burnout result in fewer Canadians being willing to serve in the medical field?

Another concern has been “pandemic fatigue” among the general population. Health experts have warned against letting down our collective guard against COVID-19. However, some Canadians have resisted what they see as draconian health restrictions. For example, across the country, citizens, businesses, and churches have been fined for flouting bans on large gatherings, while others have publicly lamented a perceived loss of personal liberties. The United States in particular has seen widespread anger and sometimes-violent protests.

Advertisement

Pandemics test societies in many ways. They can weaken the social fabric and exacerbate divisions. But they can also work to bring us together. A century ago, during the Spanish flu pandemic, Ontarians responded to the health crisis by launching a massive volunteer relief effort. In Toronto, the city established twenty-four-hour supply depots, from which volunteer groups dispensed food, medical supplies, and even nursing care to hundreds of families per day. How will future generations respond to the next pandemic?

VACCINE VACILLATION

Despite his missteps, former U.S. President Trump can be credited for expediting the development, testing, and production of several COVID-19 vaccines through government partnerships with pharmaceutical companies. This initiative, dubbed “Operation Warp Speed,” officially launched on May 15, 2020. Through it, the vaccine-development process, which normally takes several years, was compressed into less than a year, without sacrificing regulatory standards. The operation succeeded in bringing the highly effective Moderna vaccine to the public with near miraculous speed. However, this expedited vaccine development raised a variety of concerns among people who were already hesitant about, or strongly opposed to, vaccines.

Historically, anti-vaccination views date back to the discovery of the very first vaccine in the 1790s, which prevented smallpox. Since smallpox vaccine was prepared from cowpox material, which caused a mild smallpox-like infection on the bellies of calves, many people were more fearful of mixing animal and human materials than they were of the deadly effects of smallpox. Such fears of the smallpox vaccine, though they existed among a minority of citizens, helped to contribute to persistent outbreaks and epidemics. Until the mid-1920s, smallpox vaccine was the only effective vaccine that existed. Its preventive value was underscored by the generally low incidence of the disease. However, when it was not used — due to active resistance or passive neglect — outbreaks inevitably resulted.

A significant smallpox epidemic struck in Ontario in 1919, not long after the worst part of the influenza pandemic had passed. The epidemic was exacerbated by active anti-vaccine efforts that were in turn fuelled by misleading claims about the sanitary conditions involved in making the vaccine, and by a public-health policy of compulsory vaccination during smallpox outbreaks.

That epidemic prompted the U.S. government to require proof of vaccination before crossing the international border. The Quebec government imposed a similar restriction at the Ontario provincial border when smallpox broke out in the Ottawa area in 1920–21.

A historic precursor to the Operation Warp Speed plan was the development of the first vaccine to prevent polio during the early 1950s. The polio vaccine plan was led by the U.S. National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis and came to fruition on April 12, 1955.

While Canada is currently relying on COVID-19 vaccines from international suppliers, ironically, half a century ago Canadian researchers led the way in several polio breakthroughs. Connaught Laboratories researchers made three essential contributions to the polio vaccine. In 1948–49 they developed Medium 199, the world’s first purely synthetic tissue culture solution; in 1951 they showed that it could support the cultivation of the poliovirus; and in 1953–54 the Connaught team produced enough poliovirus fluids to enable a mass field trial of an inactivated polio vaccine engineered by Dr. Jonas Salk of the University of Pittsburgh. The trial results, announced with great media attention on April 12, 1955, demonstrated that the vaccine was effective in preventing polio. Unfortunately, an incident that became known as the Cutter crisis undermined the polio vaccination program in the United States.

While the Salk polio vaccine field trial was being evaluated, several American pharmaceutical firms began preparing vaccines in hopes of positive trial results. American government testing requirements, which had involved double tests of every batch of the vaccine during the field trial, were relaxed to require tests only for each company, but not for each batch. In Canada, double testing of each batch continued.

Soon after the vaccine had been licensed in the United States and Canada, polio cases were reported in children who received vaccine traced to one firm, Cutter Laboratories in California. This prompted the suspension of the entire United States vaccine rollout. Although Connaught was the sole provider of the vaccine in Canada, uncertainties about the source of the problem — whether it was inherent in the vaccine or due to a production issue with one firm — prompted the question, what should Canada do? Paul Martin Sr., the Canadian health minister, had confidence in Connaught’s vaccine and in the Canadian government’s testing protocols for it. He decided to let vaccinations continue uninterrupted.

Although the Cutter crisis ultimately led to more robust vaccine production and testing regulations and heightened disease-surveillance systems, it has nevertheless haunted the introduction of new vaccines. The Cutter crisis heightened public sensitivities about vaccine safety, planting the seeds of later vaccine hesitancies. Concerns about the pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine in the 1970s, and suspicions of adverse reactions during a mass influenza-vaccination program in 1976 to prevent a feared pandemic that never materialized, further stoked public skepticism. Vaccine fears were exacerbated in the 1990s by mistaken beliefs that measles vaccine might cause autism. Although definitively discredited, such fears persisted and were magnified in the media and, later, via social media.

Will there be a COVID-19 Cutter crisis? At the time of writing, four COVID-19 vaccines have been approved by U.S. or Canadian regulators and have been used on an increasingly large scale, without adverse reactions in the vast majority of cases. However, in March 2021, the use of the AstraZeneca vaccine was paused in several countries due to its possible connection to potentially fatal blood clotting in a very small number (fewer than 0.001 per cent) of recipients. In Canada, health experts recommended that the vaccine not be given to people under fifty-five. At the time of writing, health officials were examining the data to better assess the safety of the vaccine. Our experiences with COVID-19 vaccines now will undoubtedly impact the acceptance of future new vaccines.

PANDEMIC AFTERMATHS AND POSSIBLE FUTURES

More than a year ago, when the COVID-19 pandemic was officially declared, the prospects of quickly creating and deploying a vaccine to prevent it — let alone several vaccines — seemed poor. The key question now is, will the COVID-19 vaccines end the pandemic?

They will certainly help to end it faster. Most significantly, they will prevent the worst effects of COVID-19: serious illness, hospitalization, and death. It remains uncertain how effective the vaccines will be in preventing transmission of the COVID-19 virus from people who are vaccinated to other people who are not. Smallpox, diphtheria, and polio vaccines do interrupt the transmission of disease. Early evidence has suggested that COVID-19 vaccination somewhat reduces virus replication in the throat and nose and thus may reduce potential virus transmission. But more evidence is needed to be sure. In the meantime, until most people are vaccinated, wearing masks and physical distancing will have to continue for some time. Another question is whether the vaccines will provide effective protection from current or future COVID-19 variants.

Historically, it took several years before diphtheria was brought under control with diphtheria toxoid in Canada. Similarly, it took years to end polio epidemics after the introduction of the Salk polio vaccine in 1955. Vaccine production limits, along with initial immunization programs targeted to the most vulnerable age group, left people of younger and older ages exposed to polio until larger vaccine production, and new combination vaccines, enabled broader distribution among all age groups. Similarly, the COVID-19 vaccination rollout has initially targeted the elderly and other vulnerable groups, leaving younger people to wait at the back of the line.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

There are large gaps in immunization rates between rich and poor countries — a problem that far predates COVID-19. While polio incidence has been close to zero in Canada since the early 1960s, it remained stubbornly high in much of the developing world for decades afterward, reaching some three hundred thousand cases per year in 1988. That year, the World Health Organization launched a global polio-eradication program, which was inspired by the eradication of smallpox in 1979. Much progress has been made in eradicating polio, bringing global case numbers down to the hundreds; but getting to the final goal has been quite challenging, and the COVID-19 pandemic has not helped.

To be even discussing COVID-19 vaccine production and distribution issues involving multiple effective vaccines within one year of the start of the pandemic is quite remarkable. Nevertheless, there are many issues that relate to ensuring the equitable and consistent global accessibility of COVID-19 vaccines. Unevenness in immunization — whether exacerbated by active resistance to vaccination, accessibility challenges for certain groups or communities, or limits in global vaccine distribution and uptake — will only fuel more spread of the virus and the extension of the pandemic, as will the premature relaxation of masking, physical distancing, and public-health restrictions. Currently, there is no real prospect for eradicating COVID-19. We will have to learn to live with its threat, and the threat of its virus variants, for the foreseeable future.

Such uncertainties will complicate a “return to normal” for activities such as concerts or sporting events, especially indoors. Going to crowded restaurants, bars, or church services will remain difficult. International travel will also remain complicated. Through most of the twentieth century, smallpox vaccination certificates were widely required to cross borders, until progress towards smallpox eradication made such certificates unnecessary. Now, countries are seriously debating COVID-19 vaccination passports for people who wish to travel internationally.

For most people who have contracted the disease, a SARS-CoV-2 infection came and went without serious illness. For many, however, the long-term health effects will remain significant. Long-term effects are a common feature of both COVID-19 and polio. Variable physical disabilities, including permanent muscle weakness, are a defining element of polio, and post-polio syndrome has continued to debilitate many patients. Similarly, COVID-19 is leaving some victims with a variety of long-term physical impacts, their collective “long-hauler” experience similar to cohorts of “post-polios” who accumulated in the wake of decades of polio epidemics.

For people impacted by the broad economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as job losses and business closures, the historical precedents are few, at least in Canada since the First World War. The economic impacts of the 1918–20 influenza pandemic were comparatively limited, as were the impacts of other major epidemics like polio. A closer comparison would be with the Great Depression of the early 1930s.

It has been suggested that — assuming that widespread, successful vaccination limits virus transmission and protects against new virus variants — Canadians bursting free from lockdown could very well experience something like the Roaring Twenties again, albeit in a distinctly 2020s version.

What’s certain is that future generations will continue to face new viral and bacteriological threats. How well they contain and combat these new pathogens will in many ways be determined by their ability — and their willingness — to learn from past pandemics.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.