The Last Utopians

The abandoned farms and empty streets of Depression-ridden rural Manitoba filled the view through the windows of the railway coach as Walter Fryers, a twenty-three-year-old university student, journeyed back to Winnipeg.

It was the fall of 1936 and Fryers had spent the summer trapping muskrats in the delta of the Saskatchewan River, working for little more than “board and a bunk.” Now he was anxious to return to his science studies at the University of Manitoba.

During the long train trip from The Pas, the young student took to heart the dark reality of the dust bowl. It had been the hottest North American summer on record. Across the Prairies, dark clouds of dust rose off the drought-stricken land, burying livestock that lay dead and dying in the fields, and caking the faces of the hungry and haggard families who grimly trekked to the cities, leaving their devastated farms behind. Against this backdrop, Fryers pondered the failure of society to provide a better life for the millions impoverished by the Great Depression.

This continued to weigh on Fryers’ mind after he arrived in Winnipeg, with its bread lines and its boarded-up businesses. Here, a chance encounter — spotting a poster for a lecture on something called “Technocracy” — was to rapidly change the direction of his life.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

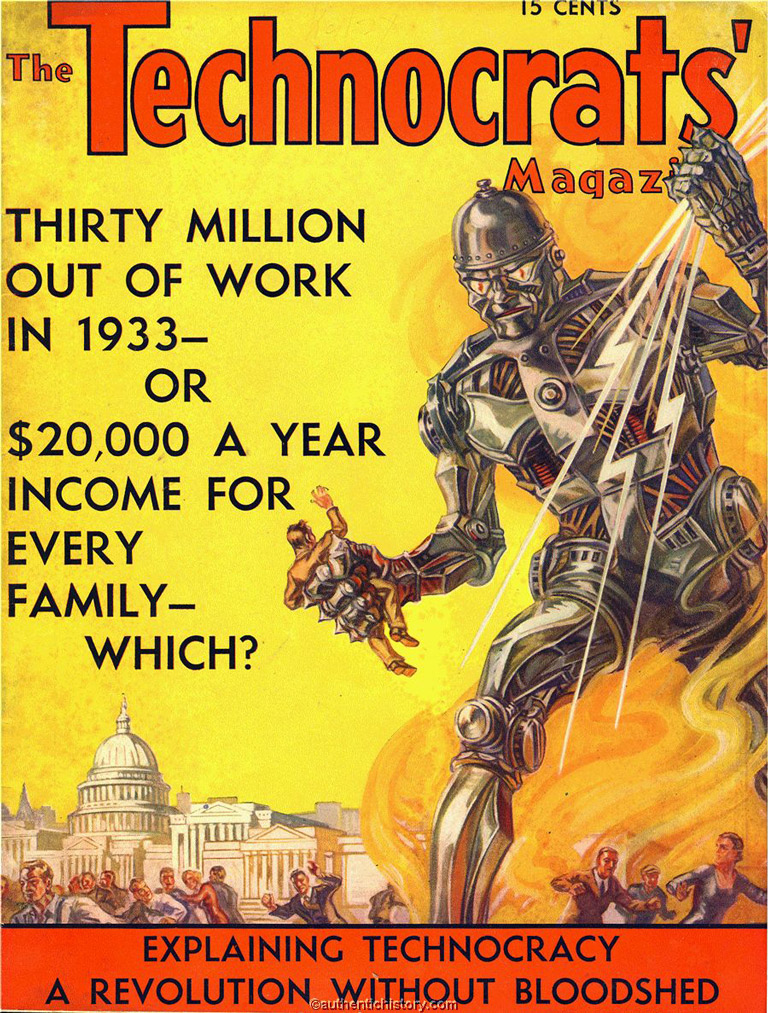

The lecture introduced the young man to a radical new doctrine that seemed to satisfy his yearning for a scientific solution to the world’s problems. Technocracy’s adherents claimed it would eliminate want by putting power in the hands of a capable few — not politicians, but an elite group of engineers and technicians, known as the Technocrats.

Within months, Fryers was himself preaching Technocracy’s merits to the media. The Winnipeg Free Press gave front-page space to his declaration that the existing economic system was the root of the problem, because, in order for it to work, “a scarcity must be created and maintained. That is why, in a world of plenty, we have widespread poverty.”

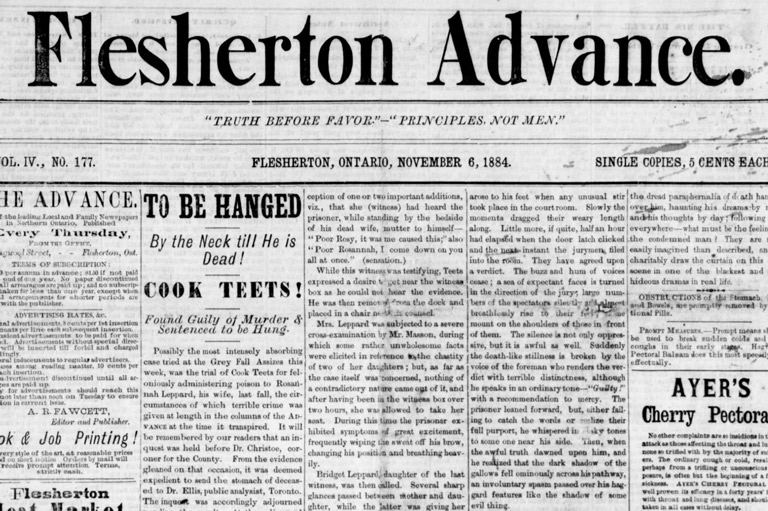

Technocracy flared like a comet in the darkness of the dirty thirties, promising to replace a collapsing capitalist system with a non-political government of scientists and technicians. It attracted thousands of members in Canada, survived a wartime banning, and enjoyed a renewed, but brief, popularity after World War II amid short-lived fears that Canada might return to Depression-like conditions.

Of all the protest movements that flowered in the Depression, Technocracy was a unique creation. Largely overlooked by historians and neglected by most political scientists, the movement never elected an MP or fomented a riot.

But to workers without jobs and farmers without crops suffering through the hungry thirties, Technocracy’s proffered world of plenty seemed a utopian paradise: Unemployment would be a thing of the past and all would share equally in the abundance of the machine age. Sir Thomas More’s sixteenth-century conception of a “happy island” stricken of all poverty and crime might at last become a reality, thanks to modern technology.

Advertisement

Founder Howard Scott’s design for what he called the “Technate of America” did away with borders and merged the United States, Canada, Mexico, and Central America into a single nation under a regime of engineers and technicians.

Political parties, along with money and all the trappings of the present price-based economic system — which Scott saw as incompatible with the distribution of industry’s output — would be things of the past. The economy would be based on energy (the capacity to perform work) and the new currency would be “energy certificates,” qualifying every citizen to an equal share of the continent’s wealth. People would work four hours per day, four days per week, between the ages of twenty-five and forty-five.

As originally conceived, there would be no democracy in the Technate — no elections, no parliaments — because, the Technocrats claimed, even in democracies, questions of fundamental importance are never submitted to popular vote. Instead, there would be a single disciplined organization under one jurisdiction that would be responsible for the smooth functioning of society.

As John Darvill, the current head of Technocracy in British Columbia has since put it: “You don’t get on a plane and vote as to whom should be the pilot.” (Today’s Technocrats, however, do propose democratic decision-making by referenda in non-technical matters.)

Adding to Technocracy’s authoritarian approach, Scott had his followers wear grey suits and encouraged them to paint their cars Technocracy grey. He also devised an open-handed salute and adopted a symbol — the yinyang, the ancient Chinese symbol representing balance — that he called a monad. Young people who were recruited were known as Farads — so named in honour of the English father of electricity, Michael Faraday.

In Canada, one of Scott’s most enthusiastic advocates was Robert Cromie, the energetic publisher of the Vancouver Sun, who launched his newspaper as a platform for “liberalism.” The two corresponded frequently.

On October 31, 1935, Cromie wrote to tell Scott that, “Each letter that you send me, or each item that comes in, I devour.” He added: “If you come to British Columbia we will work up a good crowd for you in Vancouver.”

Unfortunately for Scott, Cromie died suddenly on May 11, 1936. His sons, who took over the paper, had little interest in continuing their father’s technocratic crusade.

Even without the Sun’s support, Technocracy spread quickly in Canada — although its strength here, as in the United States, was concentrated in the West. Eight chapters were soon organized in Vancouver, and the magazine Technocracy Digest was launched. Branches were set up throughout British Columbia, as well as in Edmonton, Calgary, Regina, Winnipeg, Hamilton, and Toronto.

For many, Technocracy served as a fraternal organization. The Winnipeg Free Press reported on a 1940 technocratic wedding, noting the groom and his attendants wore Technocracy grey suits and “twelve men in Technocracy grey formed a guard of honour.” In Vancouver, a Technocracy orchestra was formed.

There were scandals and tragedies, however. George Harrop, a director of the Winnipeg branch who had sold his grocery store to devote all his time to Technocracy, was found dead in his bed in March 1940, shot twice in the head. His wife, Frances, was charged with murder. She was acquitted on grounds of insanity on the day of the couple’s twenty-fifth wedding anniversary.

The outbreak of World War II found Scott in Winnipeg predicting an economic collapse within four years. Speaking to an audience of fifteen hundred in October 1939, he also called for a referendum on “whether people wished the present price system to continue.”

By June 1940 — with the war in Europe going badly — the Canadian government suddenly announced the banning of Technocracy, along with a dozen other organizations, including Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Communist Party. In the House of Commons on July 16, Prime Minister Mackenzie King defended the ban by saying one of the objectives of Technocracy was to “overthrow the government and the constitution of this country by force.”

Walter Fryers, now ninety-four, remembers: “We were astonished when the RCMP padlocked our section premises and took records, furniture, everything. No charges were made.”

Other Technocrats were not so lucky. A Regina chiropractor, Dr. J. N. Haldeman, faced trial as a member of an illegal organization. He was acquitted. (Haldeman would subsequently move to South Africa and become a grandfather to Elon Musk.) F.E. Demorest of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, was fined $25 for having paid for a newspaper ad protesting the ban.

The conviction was overturned on appeal and, as far as is known, no other convictions were sustained. No evidence was presented that Technocracy had advocated violence and the ban was rescinded without explanation on October 15, 1943.

Scott believed that it was his plan of “total conscription” that led to the wartime ban. The government apparently took notice when he sent Technocracy delegates to a meeting of the Western Conference of Municipalities at Yorkton, Saskatchewan, on June 1, 1940. There, they presented Scott’s scheme to conscript the continent’s financial and economic resources, as well as its manpower. The ban followed shortly after that meeting.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The real reasons for the ban remain obscure to this day. Even now, more than sixty years later, some government files on the banning of Technocracy continue to be withheld from public view by Library and Archives Canada on the grounds that they could — according to Article 15 (1) of the Access to Information Act — be “injurious to the conduct of international affairs … or the detection of hostile activities.”

Some hint of what wartime authorities may have been thinking comes across from S.T. Wood, commissioner of the RCMP at the time. In An Unauthorized History of the RCMP, by Lorne and Caroline Brown, Wood is quoted from an April 1941 issue of RCMP Quarterly.

In it, Wood likened Technocracy and other banned groups to a “poison toadstool that sprang up overnight to destroy our social structure. Not until Christianity and democracy had been mightily challenged did the people realize [and then but slowly] the strength, multiplicity and deadly malice of their foes.”

The end of World War II brought renewed concern that the North American economy — which had flourished to feed the war machine — might plunge back into a depression. Technocrats quickly rebuilt, and on July 1, 1947, a caravan of 600 Technocracy cars rolled into British Columbia in “Operation Columbia.”

The convoy had begun in Los Angeles and timed its arrival for a speech in Vancouver by Scott. He filled the old Vancouver Forum with five thousand adherents, who had each paid a dollar admission and shouted Technocracy slogans.

Reporter Charles King wrote in the Vancouver Province that Scott, speaking in a “bored, sleepy voice,” attacked the press of the United States and Canada as “the most reliable source of misinformation in the world.”

Ten years later, with the postwar boom in full swing, the movement still managed to attract some adherents. One of them was John Darvill, who spotted a billboard in Vancouver advertising a lecture on Technocracy. “(I) thought it had merit but was skeptical to say the least,” recalls Darvill, who was eventually won over after attending the Technocracy course of study.

Today, Darvill — a member of Technocracy’s continental board, which operates from a rural property near Ferndale, Washington, that was purchased with a donation from a Canadian Technocrat — is one of only a few dozen Technocrats still active in Canada.

He remains firmly convinced of its inevitability. Asked what he thinks is the future of Technocracy, he answers with a question: “What is the future for us all?” Darvill claims North America will have to adopt something like Technocracy “if we are to survive as a high-energy civilization.”

Ralph Rabb is equally convinced. Like Fryers, his views were deeply influenced by the Depression. On July 1, 1935, Rabb was a six-year-old boy accompanying his father to a labour demonstration in what became known as the Regina Riot. Rabb remembers running to and fro in the crowd as a youngster.

“All of a sudden there was a huge roar,” Rabb recalls. “Everything disappeared — all my landmarks — and I was lost.”

Rabb found himself in the middle of a violent clash between police and protesters that left one officer dead, dozens of protesters and officers wounded, and at least 120 people arrested. Rabb says that by the time his father found him, police had driven most of the two thousand or so demonstrators from the city’s Market Square.

The boy grew up with a sense of justice undone, and twenty years later, as a steelworker in Hamilton, Ontario, he was an ardent member of Technocracy Inc., destined to become the closest Canadian confidant of founder Howard Scott.

Rabb is now long retired after a lifetime in the steel industry. He made more than a hundred visits to Technocracy’s headquarters in the United States and was there when Scott died in Florida on January 1, 1970.

Rabb admits to some disappointment that the movement hasn’t grown. He says he thought that by giving out information about Technocracy “something would happen, but few were interested. They only cared about their homes, getting a cottage, and so on. We were an educational organization. We weren’t revolutionaries and we didn’t put out any idea for the overthrow of any government. Now, we have an economy of planned waste — and war is the most efficient means of waste there is.”

Some critics say that the movement failed to catch on in part because Technocracy’s leaders did not put forward a concrete strategy to fulfill their vision. The initial flurry of interest during the Depression died down after the economy started to revive under U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, which put people back to work. And some dismissed Technocracy as too authoritarian and rigid.

Yet, Fryers remains a firm believer. A retired government meteorologist, he set up a Technocracy archive at the University of Alberta. He still thinks Technocracy “was and is on the right track. It has been generally misrepresented and misunderstood, but in a high-tech society like ours it will be necessary, eventually, to institute control by energy units instead of monetary units. Our body of thought is an enduring concept that may find its place in the near future.”

Charlatan or Prophet?

Technocracy founder Howard Scott was a 6-foot, 5-inch, broad-shouldered man with a magnetic (some said bombastic) personality. He was an engineer, though some questioned his credentials, and a habitue of New York’s Greenwich Village.

He attracted the support of many distinguished thinkers, including the economist Thorstein Veblen and Charles Steinmetz, the genius of General Electric. Given to wearing broad-brimmed felt hats and leather coats fitted for outdoor engineering jobs, Scott spent a decade devising the ideas behind Technocracy while running a think tank called the Technical Alliance.

He identified at an early stage many of the issues of wasteful overproduction, environmental damage, and job displacement (whether by machines or globalization) being debated today. But he underestimated the ability of technology to create new jobs, such as the vast expansion that has occurred in the ranks of knowledge workers. And he proved unwilling or unable to put forward a concrete strategy to fulfill his utopian vision.

The term “technocrat” has, over the years, slipped into common usage to describe a bureaucratic functionary, rather than an exponent of the new — and foreboding — social order Scott had foreseen for North America.

The Rise of Technocracy

- During the Depression, Columbia University funds the Technical Alliance, a think-tank, to do an “energy survey” of North America.

- The survey concludes that technological advances are throwing people out of work, thus contributing to poverty in the midst of plenty.

- The report blames the system of money and prices, saying it relies on scarcity to operate.

- It proposes passing control of society from politicians and businessmen to a “technocracy” of engineers and technical experts.

- A barrage of publicity follows. Some twenty books on Technocracy are published within a year. Technocracy groups spring up.

- The Canadian government temporarily bans Technocracy during the Second World War.

- After a brief postwar revival, interest in Technocracy declines.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!