Back in the U.S.S.R.

On March 11, 1922, at the port of New York, a large group parading red banners awaited the boarding call for the Lithuania, a Baltic-American Line steamer destined for the Latvian port of Liepaja.

A cameraman caught a mixture of joy and anxiety on the travellers’ faces as they watched Italian dockers hoist aboard their tractors, reapers, threshers, equipment for a small power plant, and countless chests and suitcases. In Russian, one of the banners proclaimed the group as the First Canadian Agricultural Commune.

The men and women who left New York that cool spring day were Ukrainians and Russians returning to Europe. By itself, this was hardly remarkable. In the early 1920s, thousands of immigrant labourers who had been trapped in America by World War I rushed back to the old land, their pockets bulging with dollars and their trunks filled with fancy American clothes.

These 140 returnees had different motives for leaving — they were members of three agricultural communes recruited in Canada and the United States to help Soviet Russia build a workers’ paradise following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

In addition to fifty-two Canadian communards (commune members), mostly Ukrainian workers from Winnipeg and Montreal, the ship carried two American collectives: the First Agricultural Commune of New York and a group of autoworkers headed for Moscow.

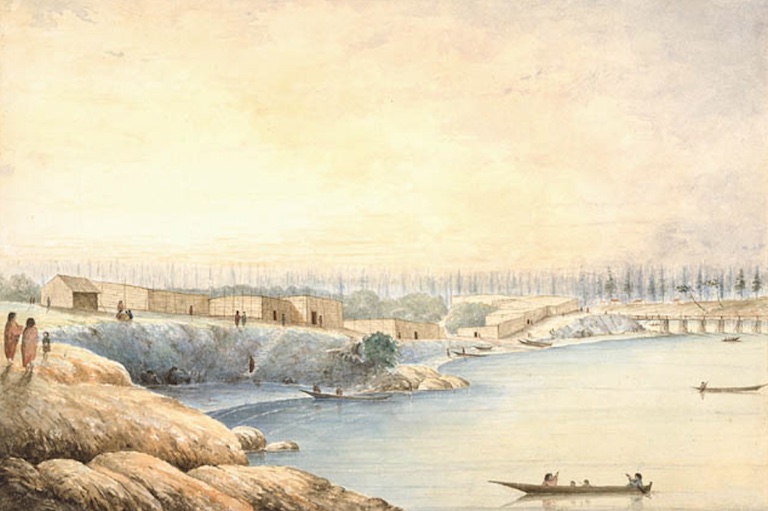

The destination of the Canadian party was Myhaiv, a village north of Odessa in the grassland steppes of southern Ukraine, where the Soviet government had given them 4,000 acres to establish a collective farm.

Attracting skilled workers and farmers was important for the Soviet state in the early 1920s. With a ruined economy and shortage of capital, Russia needed the knowledge and money of expatriate citizens and foreign sympathizers. The Soviets especially welcomed industrial and agricultural collectives, or communes, as models of mechanized cooperative labour for Russian workers and peasants.

The communes were asked to bring enough supplies, machinery, and foodstuffs to run a collective farm or an industrial establishment without taxing the resources of the state. The call struck a sympathetic chord with many American and Canadian workers, particularly among immigrants of eastern European extraction, who made up the majority in Canadian and U.S. radical organizations.

The Society for Technical Aid to Soviet Russia, established in 1919 by Russian immigrants in New York, was the main agency that organized emigration from North America to the Soviet republics. Operating from Manhattan, it coordinated the recruitment campaign among American and Canadian immigrants, purchased supplies and machinery for the departing communes, and took care of transportation and visa matters.

Formally an independent organization with its own statute and bylaws, it operated on Moscow’s instructions. It had close links to the Communist Party of America and Canadian left-wing organizations such as the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association. By 1922 the society boasted more than six thousand paid-up members and seventy-four branches on both sides of the forty-ninth parallel.

The Society for Technical Aid’s first Canadian branch opened in September 1919 in Montreal through the efforts of local Russian and Ukrainian socialists. Six years later, the society had offices throughout Canada and attracted the attention of the RCMP, which had a wide network of informants within Canada’s pro-Soviet organizations.

The First Canadian Agricultural Commune was a joint effort of the society and the Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association. The majority of its members were Ukrainian workers from Winnipeg, home of the Ukrainian-Canadian Communist movement and the association’s headquarters. Commune members had to contribute $500 ($800 for a family) and show Communist loyalty. The funds were used to purchase tractors, trucks, and farming supplies.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In 1923 and 1924, the Myhaiv pioneers were followed by two other Ukrainian collectives: the Grain Grower from Toronto and the Workers’ Field from Montreal. Both were granted land in southern Ukraine near the city of Kryvyy Rih.

Many American communes also had Canadian members. Estonian farmers from Eckville, Alberta, joined fellow countrymen in New York to organize a commune named Dawn to symbolize the coming of the new era. Ukrainians and Russians from Alberta were members of the New World, based in Cleveland, and Russian immigrants from Vancouver joined the California Commune, organized in San Francisco.

About four hundred Canadians, mostly immigrants from Ukraine and Russia, went to the USSR as members of communes.

Inspired by revolutionary enthusiasm and communist ideals, the communards envisioned a bright future in the land where workers and peasants had overthrown the czar and displaced capitalism. They had heard about the economic devastation, famine, and disease, but were set on overcoming all difficulties.

“We will have one meal and work eighteen hours a day because we know that we are in a free land,” Pavel Semenov and Ivan Palahnyuk wrote from Myhaiv to their Winnipeg comrades. For many, the desire to be part of the Communist experiment was combined with the joy of returning to the homeland.

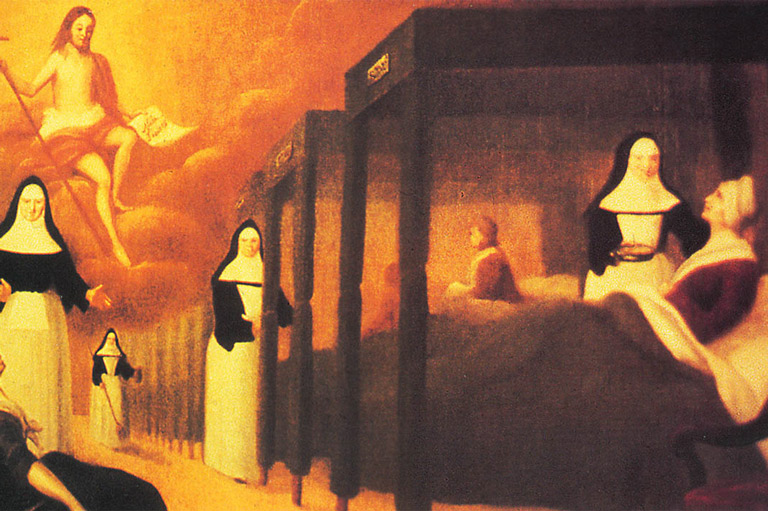

Canadian Doukhobors, members of a Russian Christian sect, were also recruited. Yearning for home was always strong among the Doukhobors, even twenty years after leaving Russia. The Soviet leadership saw Doukhobors and other religious sectarians persecuted by the czarist monarchy as allies in the building of the new social order.

Collectivist principles on which Doukhobors and other pacifist sects built their lives were considered in tune with the ideas of socialist revolution, even though they were rooted in religious beliefs rather than Marxism. The Bolshevik state highly valued Doukhobor experience in mechanized farming and intended to use it to show Soviet peasants the advantages of agricultural cooperation.

In October 1921, the Bolshevik government issued an appeal “To Sectarians and Old Believers Residing in Russia and Abroad” to return and help the agricultural development of their homeland. All were promised large tracts of land and full exemption from military service.

In July 1922, Vasily Potapoff and Larion Taranoff left for Russia as delegates for the Independent Doukhobors of Saskatchewan and Manitoba, Doukhobor dissidents who had adopted individual homesteading but continued to live in close-knit communities.

They carried a list of 280 families prepared for an immediate move and a petition asking for the right of religious instruction for their children and “full and absolute” exemption from military service. Potapoff and Taranoff chose a settlement site in the Melitopol district of Zaporizhzhya Province, Ukraine, where the Soviet authorities granted each returned Doukhobor family forty-two acres.

The first twenty-two pioneers from the Kamsack district of Saskatchewan headed for Russia in April 1923, followed by smaller parties in 1924 and 1926. Canadian newspapers reported in January 1924 that 3,000 Independent Doukhobors were preparing to immediately leave Canada.

These predictions did not come true. Mixed impressions of the Bolshevik-ruled homeland, which reached Canada through returnees’ letters, cooled the Doukhobors’ enthusiasm. Most of those who still harboured plans of returning found it impossible to sell their farms and property in Canada at a fair price.

The first encounters with Soviet realities were sobering for many returnees. They were shocked by the arrogance of Soviet bureaucrats and Communist Party bosses, the lack of elementary amenities, and the contrast between starving children and Soviet nouveaux riches strolling the streets of Moscow.

First Canadian Agricultural Commune members lived for two weeks in boxcars at a Moscow railway station awaiting a train to Odessa. Desertions began almost the day communards crossed the Soviet border.

With the exception of the Doukhobors, who received family homesteads, the immigrants were settled on former estates turned into state farms. Most farm property and buildings lay in ruin, and fields had not seen a plough for years. Everywhere the Canadians came across reminders of the revolutionary war and the famine of 1920–21. Sometimes these were gruesome: when men from the Grain Grower began digging a well, their spades hit a pile of human remains.

Because of a shortage of locomotives, it took months for their machines and property to arrive at the commune sites. The new arrivals had to put up makeshift sheds and buy horses and ploughs from local peasants. They were baffled by the extent of capitalism reintroduced into the Soviet economy after 1921, when Lenin’s New Economic Policy replaced the nationalizing drive of the early postrevolution years.

Communal savings melted away, spent on food, livestock, tools, and materials at steep prices. The high cost of gasoline and lack of parts for American-made farm machinery were the hardest to bear. In 1930, only one of the six tractors the Grain Grower had brought from Canada still worked. To supplement meagre incomes, men worked in the Donets Basin coalmines in eastern Ukraine, learning the art of bribery and cheating from the local miners.

The drain of members was another headache. The first to disappear were those who joined a commune simply to get admission to Soviet Russia. To fight desertion, many communes adopted statutes that prohibited leavers from claiming their share of the common property and money. Anyone withdrawing from the Myhaiv commune could receive only a three-day supply of food.

Disillusioned by the communist experiment, some members wrote to relatives and friends in Canada or the U.S. for prepaid tickets to return to America. “We have made a big mistake and got into a plight, and we ask you to save us, not let us die and please take us back to America,” Ivan Kurilov of the New World commune begged of friends in Cleveland.

By 1925 the Grain Grower had lost more than a third of its members. By 1930, even the relatively successful First Canadian commune had only a third of its 124 original members.

The Doukhobor resettlement campaign was particularly disastrous. By 1925–26, conflicts with Soviet bureaucracy, anti-religious propaganda, and the animosity of the local population, who perceived them to be kulaks (a derogatory Russian word for well-off peasant) forced many Doukhobors to ponder leaving again.

The first Doukhobor families returned to Canada in the fall of 1927. The next year the Soviet government broke its promise to exempt religious sectarians from military service and almost all of the remaining settlers fled. Canadian immigration officials were obviously pleased. Frederick Blair, assistant deputy minister of immigration, called for their speedy re-admission: “The effect of their return would be to kill propaganda by the Soviet Agents and at the same time make these people and their friends a lot more contented than they have been in the past.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The three Ukrainian-Canadian communes held on. One way of coping with desertions was to woo “class-conscious elements” among the local peasantry. The first reaction of the locals to the appearance of the “Canadians” in the area was usually cool. The communards’ North American outfits, strange dialects peppered with English words, and their openly professed “godlessness” bred suspicion and mistrust.

Peasants in Myhaiv believed, for instance, that the newcomers were agents sent to take back the land of their former landlord, wealthy German colonist Johann Keller. But as years passed, attitudes improved. Tractors and other machines mesmerized the peasants, who had rarely seen a vehicle other than a horse-drawn carriage.

When the economic performance of the communes eventually surpassed the production levels of most individual households, caution gave way to genuine interest and inquiries about membership. Every candidate was carefully screened for anti-Soviet beliefs and any traces of a kulak background.

The Myhaiv commune was among the more successful. In 1924, it owned 17 buildings, a steam-powered mill, 46 horses, 91 head of cattle, and 210 pigs. But the communards had to abandon their naïve belief in the arrival of communist society that would immediately follow the proletarian revolution.

They tried to introduce money-free economies based on the famous communist dictum “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” Members lived in shared quarters, ate together, and were not allowed to own individual property. But it was soon learned that such a system penalized hard workers and rewarded idlers.

In the late 1920s, the commune introduced differential wages depending on the workers’ qualifications and the type of work. A fixed portion went to the communal treasury, but extra earnings could be used to purchase personal items.

Soviet authorities declared the Canadian group a “model commune” and turned it into a showcase of socialist farming. Visits by international Communists such as Myroslav Irchan, a renowned Ukrainian writer, were especially welcome. Irchan had edited The Working Woman, a Ukrainian Communist weekly in Winnipeg.

In 1930, he visited Myhaiv, describing his impressions in a series of sketches entitled A Prairie Oasis. Ukrainian Labour News, the leading organ of Ukrainian-Canadian Communists, reprinted his essays and photographs of the commune’s idyllic life. Four years later Irchan became one of the early victims of Stalin’s purges and disappeared in the gulag.

While most of the Canadian communes survived and some succeeded, the movement of new members from Canada slowed around 1924 and virtually stopped in 1926. Letters from disillusioned communards and stories carried back to Canada by returnees discouraged others, and the Roaring Twenties ended the unemployment and pessimism that had fuelled eastern Europeans’ re-emigration to the USSR. Also, American and Canadian Communist organizations complained to Moscow about the exodus of their best cadres.

By the 1930s, Stalin no longer needed immigrant communes to convince Soviet peasants of the merits of cooperative farming. Brutal force was faster and easier. All immigrant communes were converted into standard collective farms and assigned hefty production quotas. A few years later Stalinist repressions struck. Those with North American connections were easy targets as “agents of world imperialism.” Many Canadian communards were shot by Soviet secret police or died in labour camps.

Today, a traveller in the southern Ukrainian steppe can still see the ruins of Keller’s mansion, once the living quarters for Myhaiv communards. With the headstones in the local cemetery, they stand as sombre monuments to the hundreds of Canadians of the 1920s who dreamed of building a communist utopia and found a nightmare.

In with the new

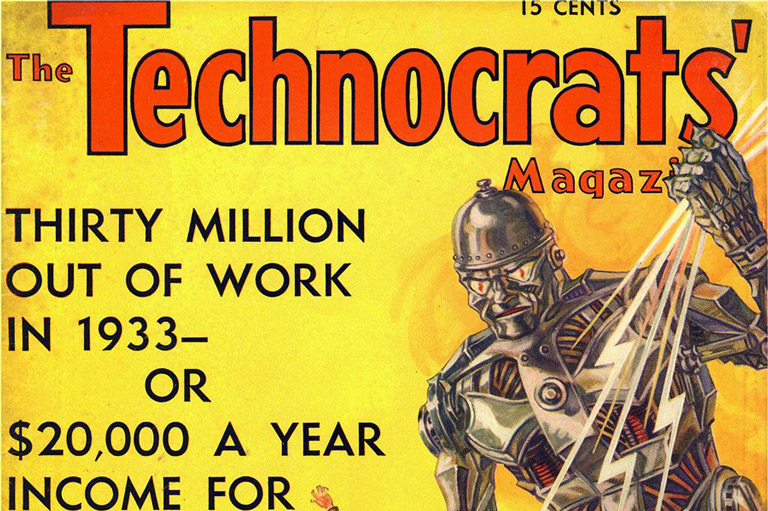

For idealists, the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 brought forth a new, socialist era in human history. But conditions within Soviet Russia in the years immediately following the Revolution thwarted any easy transfer to socialism. Civil war between the new Communist regime and its enemies wracked the countryside; by 1921, the Russian economy was in steep decline, with both industrial and agricultural production a fraction of pre-World War I levels.

Lenin had adopted a program of extreme centralization during the civil war, but faced with the realities of the economy and the fact that 85 percent of Russia’s people were peasants with little thirst for socialism, not the masses of urban workers Marxism required for a successful proletarian revolution, he instituted in spring 1921 the New Economic Policy — in effect, a pragmatic retreat from the strictures of communist orthodoxy.

Under the NEP, peasants could lease and hire labour and retain excess produce to sell for a profit. Villagers could, within limits, manage their own economic lives as they saw fit. Under the NEP, which included reforms for industry and commerce, the Russian economy began to revive and by 1928 agricultural and industrial production had been restored to the 1913 level.

However, the program, with its relative liberties given to private trade, was repugnant to organized workers and committed Marxists in the Bolshevik party. Whether Lenin had intended the NEP as a temporary measure or a permanent policy is unclear. He died in 1924.

His successor, Joseph Stalin, departed from the NEP and eventually enforced full central planning and the collectivization of agriculture. In the 1930s, Stalin initiated the Great Purge to rid the Soviet Union of dissidents. It was during this campaign that Canadian communards were persecuted.

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

- Arts, Culture & Society

- Business & Industry

- Military & War

- Peace & Conflict

- Politics & Law

- Science & Technology

- Settlement & Immigration

- Industry, Invention & Technology

- War and the Canadian Experience

- Provincial/Territorial Politics

- Social Justice

- Religion & Spirituality

- Canada and the Global Community

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!