The Plot to Buy the Canadian Northwest

The two men met on the night train from New York to Buffalo: the promoter and the respectable Toronto businessman. As the train chuffed up the darkened valley of the Hudson River, the promoter confided that he was working on his biggest deal ever.

Quite simply, he planned to buy up the Canadian Northwest — from Manitoba through to the Rockies and all the vast lands to the north — and sell it to the United States.

In the summer of 1884, the Canadian West was wracked by discontent and the scheme of promoter E.A.C. Pew from Welland, Ontario, was not quite as bizarre as it now sounds. In the swaying smoking compartment, possibly after a drop of whisky, he may even have sounded convincing as he told his astonishing story.

He had, he explained, just come from Washington, where he had received private and informal support fro his plan to bring about, first, the secession of the North-West, then commercial union with the United States, and finally, annexation — “though of course the latter is to be kept in the background.”

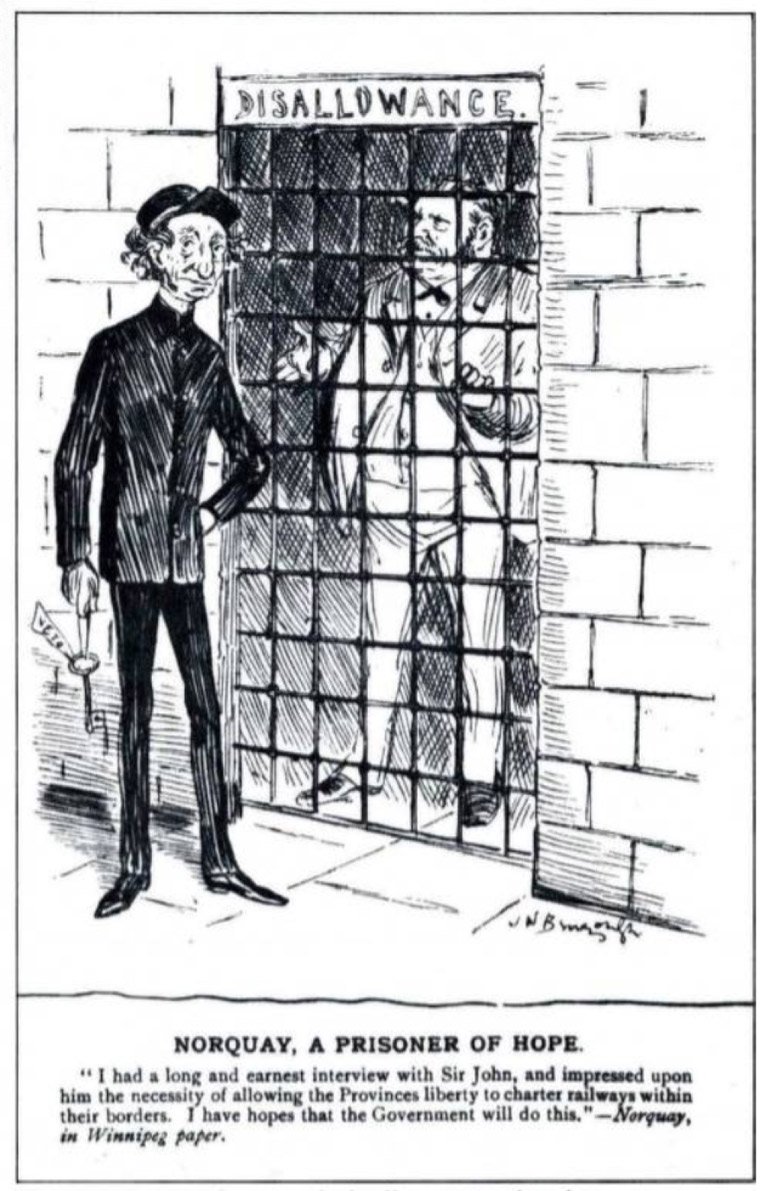

He had been assured, Pew said, that the United States would be willing to pay $25 to $30 millions, in one way or another, for the coup. The premier of Manitoba, Honest John Norquay, would be bought off with “money down” plus a United States senatorship, and Louis Riel, the Metis rebel, would be brought back from the United States to “assuage the French and half-breeds.”

At the moment, Pew went on, he was on his way back to Winnipeg to lay the groundwork there. He had already secured one of the three Winnipeg newspapers, and was working on a second.

As propagandist for the campaign, he hinted, he would have Edward (Ned) Farrer, the brilliant, amiable and hard-drinking young Irishman who edited the Winnipeg Sun — and who five years later would be deep in shadowy plots to annex the whole of Canada to the United States.

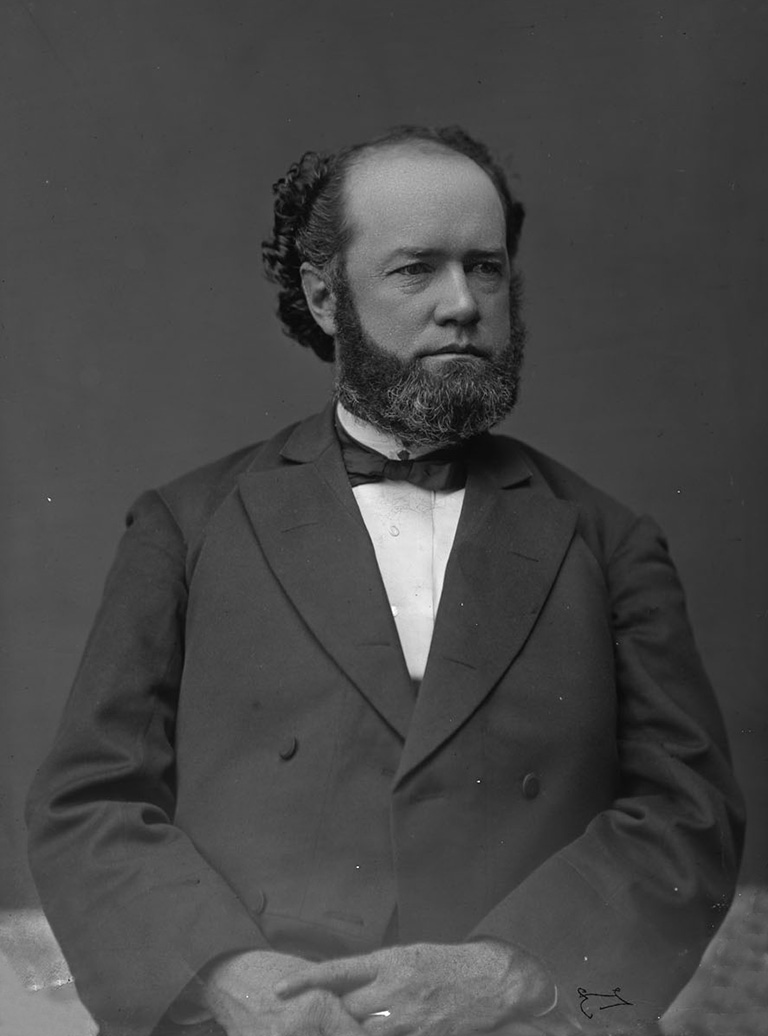

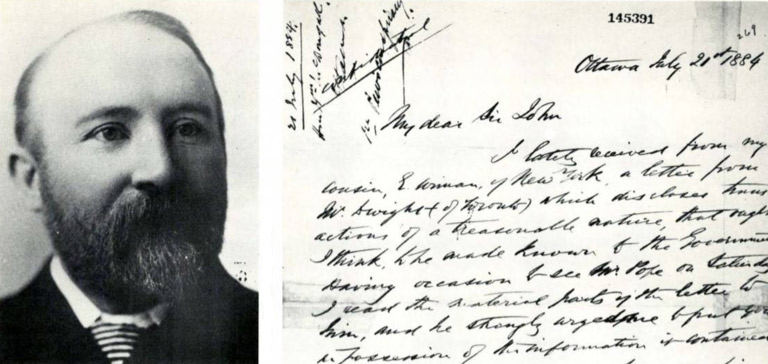

The Toronto businessman who listened to Pew’s story with growing amazement was H.P. Dwight, general manager of the Great North Western Telegraph Company.

When he arrived in Toronto, Dwight quickly set down what he had heard in a letter to his boss, president Erastus Wiman, and from there the message moved by indirect means to come before the eyes of the prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald.

The chain of communication was significant, because both men who passed on the message would become agents for Macdonald in sniffing out the plot.

The first, Erastus Wiman, was a beefy, bombastic, one-time Toronto journalist who had made a fortune in New York and would later be a leader in the movement for commercial union between Canada and the United States.

The second link in the chain was Wiman’s cousin, William McDougall, also a former journalist and one-time member of Macdonald’s cabinet, who had fallen from grace.

McDougall wrote the prime minister, explaining that Wiman had sent him Dwight’s letter, disclosing “transactions of a treasonable nature,” and said he felt obligated, as a privy councilor, to pass it on — even though his advise might not be much welcomed.

MacDougall may have seen the plot as a way to repair damaged fortunes, for he took pains to make it seem like a serious threat.

“I need not tell you who Mr. Pew is,” he told Macdonald. “You know his antecedents better than I. But whatever else he may be, he is not a lunatic. There is method in his operations, and great boldness, much cunning and utter unscrupulousness in his methods. He is also a man with a grievance. The stoppage of the South Western Railway of Manitoba has seriously affected his financial schemes, as well as the fortunes of many other more deserving people. For these and other reasons, I am inclined to believe that Pew means mischief, and circumstances just now are rather favourable to him than otherwise.”

Macdonald, vacationing in Riviere du Loup and in poor health, did not have to be told that things were bad in the West. At Winnipeg, he knew, the collapse of a hectic boom had left the raw frontier city filled with disappointed “boomsters,” always ready to plot or complain.

In the countryside farmers were organizing angrily to protest the Canadian Pacific’s rail monopoly (which barred the building of branch lines to take out their wheat) and Macdonald’s national policy of tariff protection, which forced them to pay dearly for reapers from eastern Canada.

Macdonald had already heard wild rumours of a possible armed uprising by the farmers. And farther west there was the rankling discontent of the Metis — discontent that would become rebellion the following spring.

Yes, things were not well in the West. Pew, the prime minister reflected, was a fraud, but a convincing one. And Ned Farrer perhaps involved in the plot?

Macdonald must have shaken his head in chagrin. A dozen years earlier he had seen Farrer’s talent, at a time when Ned was a young immigrant barely into his twenties, recently come from Rome, where he was said to have been studying for the priesthood.

Farrer had risien to editorship of the chief Tory organ, the Toronto Mail, when still in his twenties. He’d then had a fling in New York journalism and had come back to edit the Tory paper in Winnipeg, the Times, only to be fired in April after a “pretty extensive spree.”

Now, as editor of the Sun, he was certainly writing like a secessionist. Friends in the West had already sent vague warnings about Farrer’s activities.

For Macdonald, it was all something of a nuisance. But he considered it worthwhile to inform the Governor-General, Lord Lansdowne, passing on McDougall’s letter.

“This fellow Pew of whom he speaks I know well,” the prime minister wrote.

“He is a liar and a swindler who I found out years ago. But, as McDougall says, he is not a lunatic — is very plausible … still, I don’t apprehend any real danger from him.”

In New York, meanwhile, Erastus Wiman heard from his cousin that Macdonald had been told of the plot and he belatedly offered the prime minister his own services as a spy. He passed on a letter received from Pew (asking for a loan of $200,000) and said he had invited the promoter down to New York, so he could get all the facts of the conspiracy.

The question was, though — how far did Macdonald want him to go in getting to the bottom of the matter? Would it be worthwhile to go down to Washington with Pew, to “spend a little money” and find out all about it?

Macdonald wired him to go ahead. He also brought McDougall down to Riviere du Loup, and asked him to make a trip to Winnipeg — ostensibly to visit a sister, but in actuality to check on the conspiracy.

Wiman, once engaged, took to the role of agent provocateur with zest (McDougall seems to have produced nothing except complaints over his expenses).

On 6 September Wiman wrote to say that he had been keeping Pew on a string, leading him to believe he would be introduced to “good parties who have plenty of money” and pumping him for details of the plan.

Among other things, he said, Pew had told him of a positive arrangement with Premier Norquay, to accept $1 million in bonds of the new state.

Pew had first been “led to take action” by S. J. Ritchie, Ohio industrialist and president of the Central Ontario Railroad Company. And a number of other important Americans were in on the plan, including Senators Payne and Sherman of Ohio, House Speaker Carlisle and Judge William Lawrence, first controller of the treasury.

Wiman, acting as cat’s paw, had also introduced Pew to a number of his New York friends.

“Strange to say, quite a number of them feel greatly interested, and one or two would not be disinclined to help him,” Wiman wrote.

“Of course I do not reveal my hand, and he is quite encouraged in the belief that an agent will be sent to Manitoba before ten days are out with the money necessary to buy the press and fix Norquay and his ministers and generally prepare the way for a definite and successful independent [sic] movement.”

Wiman next wrote on 13 September, saying he had been to Washington with Pew but that the visit had not been very “productive.”

Only Judge Lawrence had seemed interested in the affair, and even he was “much more guarded” than Pew had led him to expect. Judge Lawrence, however, had seemed to think there would be no difficulty in getting Congress committed to a policy of welcoming in a seceding province.

At Wiman’s urging, the judge had also agreed to write a letter giving an indication of the American position, although he had written less freely than he had spoken. Wiman enclosed a copy of the letter, which, though cautiously worded, was certainly strong enough to have caused a scandal if it had been made public at the time.

The letter started out by saying that Lawrence was giving only a personal viewpoint, adding that he did not expect that either of the two men then contesting the presidency, James G. Blaine or Grover Cleveland, would let the United States be dragged into a war over Manitoba.

“If, however,” it went on, “the people of Manitoba should declare their independence and that independence should be recognized by Canada and by the British authorities… I think it would be very desirable for the United States to acquire it, and I believe the government would be willing to buy it… I do not think this government would hesitate a moment in paying 30 millions for so valuable an acquisition.”

(Judge Lawrence, however, showed some confusion over what exactly was to be bought, saying he understood that “Manitoba possesses an extent of country nearly equal to the whole United States territory, exclusive of Alaska.”)

Wiman passed on to Sir John not only Lawrence’s letter but also a six-page memo, dictated by Pew to Wiman’s “phonographer,” which set out the complaints of the Northwest and the prospects for the annexation movement.

In it, Pew claimed that he already had some sympathy from two of the three Winnipeg newspapers.

The “parties favorable” to the plan, he said, included “the Hon. S. C. Briggs, late provincial secretary, who is president of the company which he owns the Sun newspaper and is a man of influence and position and one of the wealthiest men in the North-West….”

He added that “Mr. Roe of the Times [presumably Amos Rowe] would not be favorable to a United States connection, though strongly in favor of independence.” And “Mr. [W. F.] Luxton of the Free Press would favor immediate connection with the United States.”

Just how committed these newspapers actually were, however, remains open to question. During the summer of 1884, Farrer’s Sun had, it is true, often complained of Manitoba’s plight, and hinted at the possibility of secession.

“We were brought into Confederation without our consent, and it can be no crime to leave it without ceremony,” it had said on 31 May, while backing Norquay’s demand for “better terms” from Ottawa.

On 7 June it was even more outspoken, after a warning from the Times (a Macdonald supporter) that Sir John might “become aggressive” if Manitoba continued to fight the terms Ottawa offered.

“The premier [Macdonald] is mistaken in thinking that we depend upon the East,” said the Sun, ominously.

“Our interests, it may be our destiny, lie to the South. If he wishes to test the matter, by all means let him “become aggressive.” He cannot strip us of much, for we are already naked. But he can succeed, if he tried ever so little, in precipitating secession; and if he desires that, it must be confessed that the ambition is mutual.”

At the end of the summer, on 1 September the Sun was still sounding the same note.

The British connection was not in immediate danger, it said, “but it is as certain as anything can be in human affairs that independence or annexation is the ultimate destiny of Canada... [T]he birth of a Canadian nation of the bloodless absorption of these provinces by the Republic… is written in the book of fate.”

If the Sun and Ned Farrer actually were allies of Pew, they took a strange way of showing it, for through the summer of 1884 the paper repeatedly savaged Pew, calling him a fraud and humbug.

That may have been partly because the Sun was a supporter of the Canadian Pacific Railway (an unpopular, but lucrative, position) and Pew as an independent railway promoter was an enemy. But that alone did not seem to call for the type of language the paper used about Pew.

On 23 June, for instance, it called him one of the city’s “cheap and noisy boomsters,” and said he couldn’t build a mile of streetcar track if given the material and the right-of-way. A week later (30 June) it went into his shady background and bluntly invited him to sue:

“He is a fraud. That is plain and no doubt actionable English. Some years ago he operated a peat factory for the purpose of extracting turf from the cranberry marshes near Dunville, Ontario. It failed, of course. A gold mine could not make money, at least the stockholders could not, if Mr. Pew conducted it. Then he started a bank at Welland. Then he went into the steamboat business, and then, according to the law of natural selection, he came to the Northwest in the capacity of general philanthropist… Mr. Pew is simply a humbug with a pious turn and a marvelous stock of impudence. We don’t want either him or his money, if he has any.”

The Sun’s destruction of Pew’s reputation (what there was of it) may well have been a factor in killing his plot. In any event, Manitobans declined to buy either Pew’s bonds or his conspiracy.

The following spring, the Metis rebellion on the plains brought a surge of loyalty through the British’ population, and the Northwest remained Canadian.

There were a number of curious postscripts, however, for each of the principal characters:

Late in 1889, while Erastus Wiman was campaigning for commercial union, Pew, too, as president of the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway Company, was writing to Macdonald, also calling for commercial union and making what seemed to be a veiled blackmail threat.

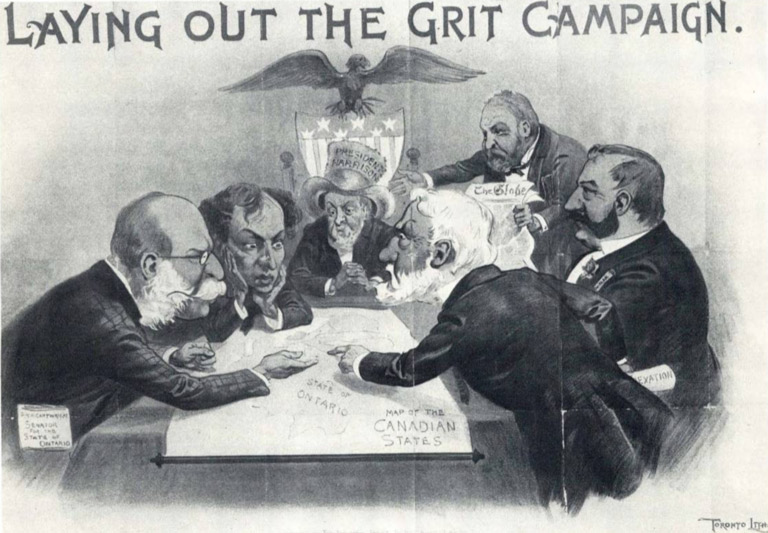

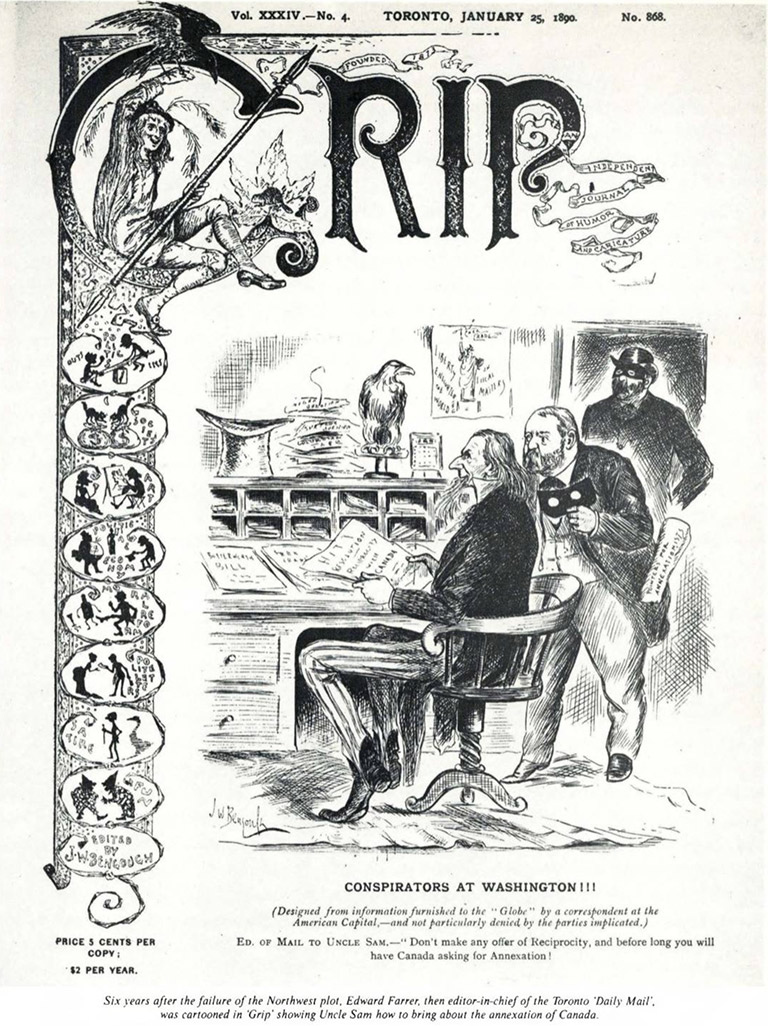

In the same year Ned Farrer, again editor of the Toronto Mail, and among those who had led in its break with Sir John, was in Washington, secretly pressing on James Blaine, now secretary of state, a plan to bring the whole of Canada into the union.

Two years later, when Farrer had switched to the Toronto Globe, S. J. Ritchie was said to have supplied that paper with $50,000 to fight Macdonald in the election of 1891, and to strengthen the paper’s continentialist leanings.

William McDougall, in the same election campaign, offered, in exchange for the promise of a senatorship, to give the government letters to Winman that implicated Farrer as an annexationist. (Always a loser, McDougall got the promise, but not the senatorship.)

In the climactic rally of the election, at Toronto’s Academy of Music, Macdonald exposed a pamphlet, allegedly written by Farrer, which advised the Americans how to bring about annexation.

The exposure was crucial in allowing Macdonald, just a few months later, to die in office. The Old Chieftain could not have known it at the time, of course, but he had quashed the last serious annexation movement in Canada.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Wouldn’t your magazines like to slip into something more comfortable?

Preserve your collection of back issues with this magazine slipcase beautifully wrapped in burgundy vellum with gold foil stamp on the front and spine. Holds twelve issues.