The Bank That Went Bust

“This is not a begging letter, Sir,” wrote Mrs. Hill of Toronto’s 45 Sackville Street in her brief note of August 22, 1923, to T.L. Church, her local Member of Parliament. It is “to ask you to try to get our money back, if it is humanly possible, for the poorer class at any rate.”

The “money,” — $234.19 (roughly $2,600 today) — was put aside, said the desperate woman, for the coming “winter’s supply of clothing and coal” that she, her husband, and their two small children would surely need. She had “banked” most of their cash in May, for fear she would “lose it” at home.

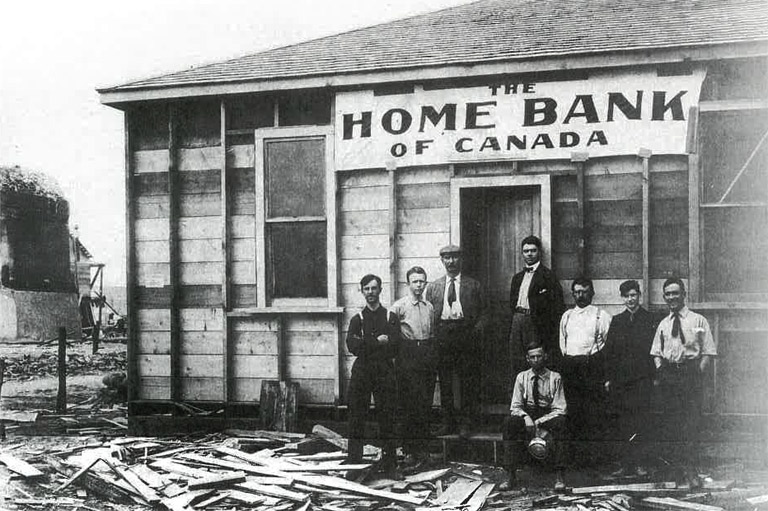

Five days before pleading to Church for help, Mrs. Hill had been enjoying the warm, sleepy Friday afternoon in Toronto and had decided to deposit another $40 in the small bank she had come to trust with her family’s money. She did so at precisely 2:30 P.M. Her peace of mind, and that of roughly 60,000 other Home Bank depositors from Quebec to Fernie, British Columbia, was shattered thirty minutes later when the seventy-one-branch, Toronto-based Home Bank of Canada shut down. Much of Mrs. Hill’s savings, and those of others, was gone.

With the Home Bank went an era when many had faith in the transparency of their banks, and national governments were keen to stay out of the business of banking. What followed saw many Canadians turn to government to underwrite their banks’ honesty and politicians increasingly feel comfortable intervening in the business of banking in the name of the public good.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Acrimony spoiled the party when Parliament opened in November 1867. In October, the divide between Canada’s first finance minister, Sir Alexander Galt, and his cabinet colleagues, including Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, was laid bare. Galt wanted Ottawa to intervene and save failing banks, smooth over economic upheaval, rescue ruined depositors, protect debtors from having their loans called before they were due, and bail out bank investors as well as bank executives who exercised bad judgment using the public purse to finance the entire process. Galt had support in Ontario, but not where it counted, in Macdonald’s cabinet, which rejected his pleas for an interventionist policy. After the pomp and ceremony of the opening day of Canada’s first Parliament, Galt resigned. His failure to persuade Macdonald and others reflected the reality of the new government’s troubled finances.

What to do about banking claimed Canada’s second finance minister, Sir John Rose, a little less than two years later. Rose took to heart demands for a sound banking system, inspired in part by the 1866 failure of the Bank of Upper Canada, which left Ontario without a large bank capable of competing with the Montreal-based Bank of Montreal, the biggest North American bank in 1867.

Rose, a Montreal MP and friend of Macdonald’s, proposed legislation modelled on U.S. federal banking law. Though it made safety a priority, many businessmen, farmers, and bankers in Ontario and the Maritimes felt safety came at the expense of competition and access to bank credit needed to grow the new national economy. Like Galt before him, Rose failed to inspire cabinet confidence. Macdonald withdrew Rose’s proposed legislation in May 1869, and shortly thereafter once again sought a finance minister who could deliver a blueprint for banking that would not threaten the stability of his government. Macdonald turned in the end to an old hand, Sir Francis Hincks, who, after a long political career in pre-Confederation Canada, had been absent from politics for a decade.

Hincks’s solution was presented in the Bank Act, 1871, legislation that was promoted as the answer to demands for safety. It proved nothing of the kind. It did not even define a bad debt, which allowed imprudent bank managers to hide their losses.

Advertisement

While the Dominion government issued currency valued at $4 or less, banks issued their own bank notes, the bulk of the country’s currency, on the proviso that they not exceed the value of the bank’s capital, which was to act as insurance to note holders if the bank failed. But Ottawa neither enforced this precaution nor required minimum reserves to keep a bank strong in bad times. Canada’s banks would be entirely self-regulating despite the public perception that the government had put new safeguards in place–a perception created, for example, by monthly statements from the banks listing their assets and liabilities that were published by Canada’s finance department. Neither Hincks nor Macdonald, however, wanted the government tangled up in regulating the banks and did not require the banks’ submitted statements to be verified. Their accuracy was only ascertained, admitted a finance official years later, “after an investigation of the affairs of the Bank and in that case ... the guilty parties are generally out of reach before the false character of the return is discovered.” Hincks’s Act called on bankers to be transparent. Some lived up to the challenge, but a good many, including those who led the Home Bank, did not.

The Home Bank of Canada’s roots reached back to 1854 when it operated as the Toronto Savings Bank, an institution launched by Catholic senator James Mason and promoted by priests to their largely working-class, Irish parishioners. In 1905 Mason obtained a federal bank charter and turned his provincial savings institution into a federal bank so that it could expand to other provinces. This allowed him to collect more deposits that he could convert into loans for stock, bond, and real-estate speculators who found fortune in the economic prosperity that lifted Canada’s economy to new heights after 1896.

One of those speculators was the eccentric Sir Henry Pellatt, a millionaire mining and utilities promoter who was a friend of Mason’s son, James Cooper Mason. Pellatt had met Mason when he joined the Queens Own Rifles of Canada in the early 1890s, and had relied on the Masons to bankroll speculative land deals in Western Canada that made him rich. When the company became a bank, Pellatt had no intention of taking his hand out of the till, and the Masons, who controlled the bank, saw no reason to ask him to.

Six years later, in 1912, with an economy heading into recession, Pellatt owed the bank the astounding sum of $4.5 million (or $75 million today) and had just started building his Toronto vanity project, Casa Loma, which, when finished in 1914, cost an estimated $3.5 million. Pellatt’s loans were not being repaid; other very large and reckless loans made by Mason were equally unproductive. Together they compromised the Home Bank’s liquidity.

Thus was the state of the Home Bank when the spectre of war shook world markets in the summer of 1914 and crippled the finances of Canada’s Conservative government, led by Robert Borden. To bolster confidence in the banks, which had suffered runs on deposits in the days before war was declared on August 4, Canada’s finance minister, Thomas White, in consultation with a small group of the country’s senior and most trusted bankers, devised the Finance Act, 1914. The act departed from Macdonald’s non-interventionist banking policy, essentially turning Canada’s treasury into a central bank that would offer banks loans to tide them over during bad times. It also gave the government a mechanism to increase the supply of credit to the banks and, through them, to farmers and businesses, boosting the economy in the process. The Home Bank was one of the first to knock on Ottawa’s door.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The Masons wanted $450,000, but they needed to provide the government with appropriate collateral, something they did not have. The bank should have been closed immediately, but Canada was at war, its own finances were in bad shape, another bank, the Bank of Vancouver, had just failed to great public outcry, and for the sake of maintaining stability the finance minister hoped a loan combined with time would cure what ailed the Home Bank. In the end, it made it much worse.

Within a year White would regret his decision. The government loan to the bank had forced the senior Mason, who acted as the bank’s general manager, to crack open the books ever so slightly to some Toronto Home Bank directors who wanted to know why the Home Bank was applying to Ottawa for a loan. One of those directors informed the Home Bank’s Winnipeg branch manager, W.H. MacHaffie, that the bank was in “a most serious state of affairs.” MacHaffie soon told the bank’s three western directors, led by the president of the influential Grain Growers’ Grain Company, Thomas Crerar, about the suspected problems.

Crerar saw the Home Bank as a welcome addition to the West and its credit-hungry farmers. The Grain Growers’ Grain Company had benefited from that competition, obtaining needed loans from the Home Bank, yet Crerar wanted answers. In Toronto, he hit a wall of silence. Crerar responded by asking White to investigate.

Crerar’s persistence drew the ire of Edmund Bristol, a Conservative MP from Toronto who was personally indebted to the bank for more than $30,000. With his business partners, Charles Barnard, a Home Bank director and Montreal investment dealer, and W. Grant Morden, a Canadian-born British MP and deputy chairman of Canada Steamship Lines, Bristol had used influence to win a large deposit from Ontario’s Conservative government, which was part of a larger scheme to obtain financing from the Home Bank for a railway in New Orleans. Bristol, not wanting his plans spoiled, hired private detectives in a vain attempt to discredit Crerar and the other two western directors. Crerar was clean, but Bristol had little to worry about. Mason made sure he received the financing he was after.

Nevertheless, White could not ignore Crerar’s request and turned to his friend and trusted lawyer, Zebulon Lash, vice-president of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, who examined the state of the Home Bank. By 1916 he had found that three times the bank’s capital was locked up in four large loans, including those to Pellatt, Bristol and his partners, and other Home Bank directors living in Toronto. Lash should have recommended the Home Bank be closed. Instead, he advised little more than cosmetic changes, asking that the seventy-three-year-old Mason be removed as general manager. He soon retired, only to be replaced by his equally incompetent son, James Cooper Mason.

While the self-dealing financiers in charge of the Home Bank were running the bank into the ground, Canadian banking itself was going through an important transformation that had started just before the war and that the war had accelerated. Canada’s banking industry was consolidating. Unenterprising institutions were, with government approval, being merged with stronger competitors, making the country’s banking system more stable in the process. One merger, the 1921 deal that joined two of the country’s largest banks — Merchants Bank of Canada and the Bank of Montreal — ensured stability, but at the same time it chipped away at the faith Canadians had in their banks.

The merger was not one of equals. The 400-branch Merchants Bank of Canada was badly mismanaged and faced $8 million in losses, equal to nearly $80 million today. The Merchants’ shareholders saw a large portion of their capital wiped out. The Bank Act, 1871, fiddled with over the years but still largely intact, had proven inadequate to the task of protecting bank investors and customers. The only good news was that Merchants Bank was not too far gone for the Bank of Montreal to save.

The new Bank Act, designed to prevent another Merchants Bank fiasco, was introduced in March 1923 by Liberal finance minister William Stevens Fielding, the former Nova Scotia premier who had served as finance minister in Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s governments from 1896 to 1911. Auditors from two different firms would now be required to report to each bank’s chief executive and its board of directors suspect transactions and large loans, ensuring directors were far more accountable to shareholders. Moreover, to guard against conflicts of interest, a bank’s external auditors were prohibited from taking retainers or other business from their clients. The legislation was passed but was given little chance to show its true value before it was superceded by legislation that came on the heels of the Home Bank’s collapse.

The fundamental change contained in the 1923 act concerned bank statements to Ottawa. Common accounting rules would now govern bank balance sheets. Market valuations, rather than future expectations, were to be enforced under threat of legal penalties. Most significant was the standard definition of a bad loan. Hincks’s Bank Act had allowed bankers to use whatever definition they wanted for a bad loan. This would no longer suffice. The days when a loan could go unpaid for years and be reported in good standing were numbered.

On August 9, 1923, as the Home Bank’s day of reckoning loomed, James Cooper Mason succumbed to a four-month battle with cancer. In his absence the new assistant general manager, A.E. Calvert, discovered a banking horror story. Calvert laid his findings before the bank’s president, H.J. Daly, who scrambled with other officials to obtain a bailout from Ottawa barring a merger with another bank. Neither was possible. The Home Bank’s bad loans had climbed to $7 million. By August 17, the day Mrs. Hill made her last deposit, the scrambling was over. There was no hope for the Home Bank of Canada.

The money Mrs. Hill was to use to buy clothing and coal for the winter seems but a small loss compared to the hardship the Home Bank’s failure caused many of its customers. In Fernie, B.C., then a mining town where the Home Bank was the only bank in town, disabled miners lost a large share of their life savings needed to pay health-care costs. Committees of depositors were established across the West and in Ontario. Church groups took up the cause and looked to the Canadian Bankers Association to come up with the money from their members to repay the deposits belonging to the Home Bank’s customers. They also turned to the federal government, demanding not only an investigation but compensation as well, arguing rightly that the government knew the precarious state the Home Bank was in years before and should have closed it then.

Canada’s banks delivered the assistance they could, lending against what assets the Home Bank possessed so depositors could withdraw 25 cents on the dollar. The National Depositors Committee, which was established to press the case against the government for not protecting depositors, did not see its efforts rewarded till 1925, when government legislation used public money to pay Home Bank depositors another 35 cents on the dollar for deposits of up to $500. No compensation was given for bank balances above $500.

Criminal and civil charges were brought against a large number of Home Bank officials in December 1923, but to no avail. They were charged under the provisions of the bank act Hincks designed in 1871, which offered little satisfaction to the Mrs. Hills who were their victims.

At least one suicide (probably more), great hardship, and demands for political reform in Ottawa sprang out of the Home Bank’s collapse. For the future of banking in Canada, it rang the death knell for the revised bank act Fielding had proposed in 1923 that would have given shareholders far more control over their banks than had been the case since Confederation. Shareholders’ trust in bank directors, bank executives, and auditors paid to examine the books of banks had all been badly damaged. The courts seemed incapable of holding those who had wronged depositors and investors to account. Government inspection, however, offered solace to voters that, should another Home Bank ever occur, at least politicians could be made to account for their failure to safeguard the interests of Canadians who relied on banks being safe places to do business.

The transparency called for by many in 1867 was enshrined in Fielding’s original 1923 Bank Act. It came too late and was seen as too little by a great many Canadians when it did come into force. The Home Bank affair planted deep suspicions about the integrity of bankers and even the merits of capitalism. Shareholders and their auditors did not seem to be capable of guarding the public interest in Canadian banking. That role was taken over by the federal government, which created the Inspector General of Banks in 1924 to supervise banks. The decision ended once and for all Sir John A. Macdonald’s five-decades-old policy that the business of banking was the business of bankers. In turn it gave rise to the face of banking today and the political predilection that banks are a public utility to be dictated to by politicians in the name of the public good.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!