Guarding the Gold

“Hope you won’t mind our dropping in unexpectedly like this, but we’ve brought along quite a large shipment of fish.”

Such was British banker Alexander Craig’s greeting as he stepped off the train at Montreal’s Bonaventure Station late on the afternoon of July 2, 1940. And so proceeded one of the strangest and most unlikely sagas ever to come out of World War II history, the story of a mission conducted in such secrecy that even now, six decades later, the sparse details of Canada’s involvement remain largely archived at two Canadian landmarks.

Waiting on the station platform that July afternoon were David Mansur and Sidney Perkins, both with the Bank of Canada, both puzzled by Craig’s remark. Unbeknown to them and most other Canadians, the train that had delivered Craig and a small contingent of senior British bankers also carried 2,229 bullion boxes, each containing four bars of gold, with a total value of £30 million sterling.

Also onboard the sealed train, which had travelled from Halifax Harbour, were five hundred boxes of marketable securities conservatively valued at £200 million. The total shipment of bullion and securities that had arrived in Halifax aboard the Emerald, at that time the largest transfer of wealth ever undertaken in the history of the world, represented a sizable portion of England’s treasure, and its perilous journey to Canada signified a desperate attempt to keep it out of Nazi hands.

It was the first of many daring shipments to be carried out under the code name Operation Fish.

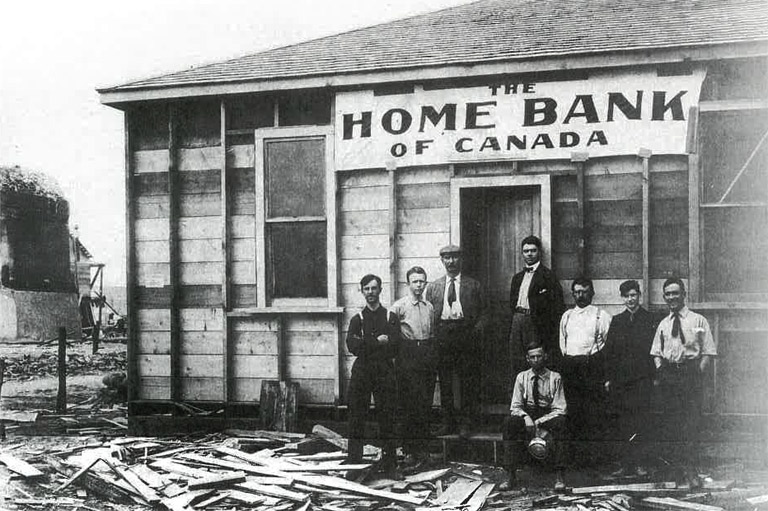

Canada’s prominent role in the evacuation of British and European gold had not been chosen at desperate random; in fact, the scene for Canada’s involvement had been set a good half decade earlier with the establishment of a Canadian central banking system in 1935.

As one of the last industrialized Western countries to enter the world of central banking, Canada was eager to avail itself of the guidance offered by the venerable Bank of England on Threadneedle Street, in the heart of London’s business district.

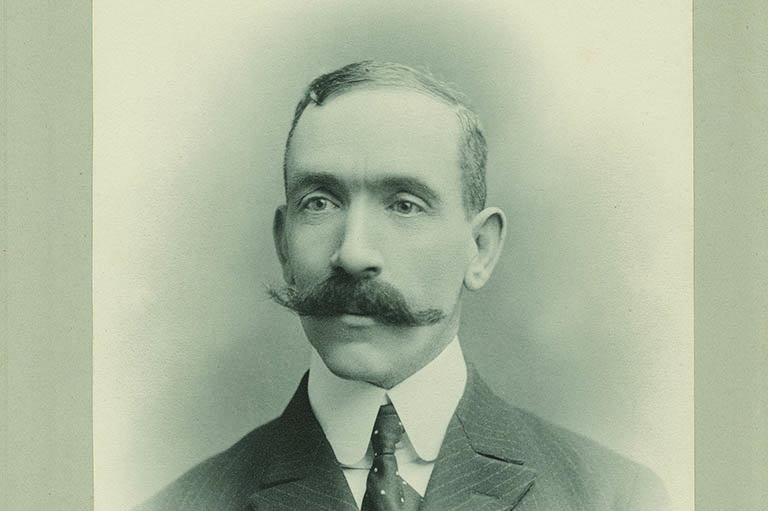

The Bank of England, since 1920 under the directorship of the redoubtable Montagu Norman, had an especially keen and self-serving interest in the promotion of central banking in the Commonwealth. And so it was that Norman and the Bank of Canada's young governor, Graham Towers, developed an unusually close and cooperative relationship that would, according to Due Diligence, a report prepared for the Bank of Canada in 1997 by Carleton University history professor Duncan McDowall, have “practical outcomes for the young Canadian organization.”

By early 1936, Britain had begun purchasing and holding earmarked gold in Canada; that is, gold minted and bought in Canada and kept there for safekeeping or trading. The Bank of Canada’s regulations permitted earmarked gold accounts, and though the Bank of England’s interest in storing its wealth offshore may have seemed unusual to Bank of Canada officials, it was not implausible given the early signs of German aggression on continental Europe.

Throughout 1936, England continued to expand its earmarked account because Canada was considered safe and convenient.

Safe, according to McDowall, "because Ottawa and London had established a close and friendly central banking system.

Convenient because the Royal Canadian Mint supplied gold at an attractive price and also because the Bank of Canada was, relatively speaking, on the doorstep of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, where the Bank of England had frequent business to transact."

By year’s end the Bank of England had stockpiled 3,304 gold bars, each worth US$14,000, in its Ottawa account. Twelve months later the number of gold bars had grown to 4,748.

In early 1939 British financiers discreetly inquired whether the Bank of Canada would agree to receive and preside over gold to be shipped from Britain in the event of war. Although England’s prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, had successfully staved off German aggression in September 1938, and war was thought by many to have been averted, London nonetheless remained vigilant to the possibility of conflict.

Records of inquiries clearly show that England’s earmarked account in Canada was now being viewed in a different light. No longer merely a means of acquiring Canadian gold, the account was to become an offshore repository for England’s own gold stores, safely beyond the reach of potential European enemies. In more straightforward terms, British gold in Canada would ensure Britain’s continued ability to purchase war equipment from the United States on a cash-and-carry basis, should this become necessary.

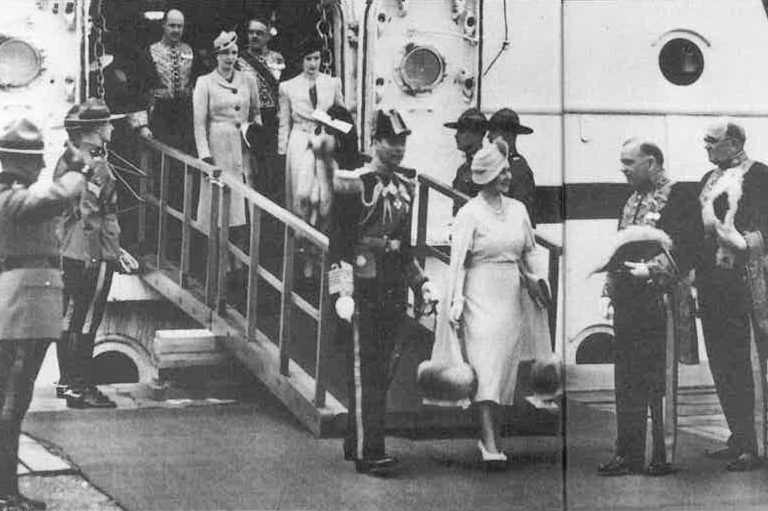

With this ulterior motive in mind, the British government seized an unorthodox opportunity to send a first major shipment of bullion across the Atlantic. Three empty warships were to escort King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on their long-planned, spring 1939 visit to Canada.

Treasury and Bank of England officials quickly hit upon a clever ruse to use the king’s visit as a cover for transporting £30 million of gold. Each of the ships would carry £10 million. When the king decided at the last minute that the battle cruiser Repulse was more urgently needed at home and would therefore accompany the party only halfway across the Atlantic, the bullion was redistributed between the two remaining ships.

In a December 4, 1995, article in the Ottawa Citizen, Forbes Hirsch, in 1939 a junior accountant with the Bank of Canada, recounted his role in the transfer of the royal gold shipment from the port of Quebec to the Bank of Canada’s Ottawa vault.

On his arrival for work on the morning of May 16, the unsuspecting Hirsch was told he would be travelling by private, heavily guarded train to an undisclosed destination where he would await further orders. Those orders came in Quebec City, against the backdrop of two mighty, gold-laden ocean liners berthed in the harbour. His job was to check each box of gold against the ships’ manifests as it was brought out of the holds and across the dock, and then loaded onto two private trains.

In Ottawa, under cover of darkness, the process was repeated as the boxes were transferred to trucks for the short journey to the huge vault. When the final counting and recording was completed two weeks later. Hirsch returned to his desk and resumed his day-to-day duties.

At the time of the royal voyage, several European nations were already making arrangements to ship their gold to London for safekeeping. Among them were Norway, Belgium, and the Netherlands, much of whose treasure would eventually end up in the Bank of Canada vault for the duration of the war.

The incoming volume was evidently significant, since one young Bank of Canada employee, who had remarked in 1938 that the Bank’s new vault seemed as “cavernous as Fort Knox,” noted in mid-1939 that already gold was “by necessity being stacked on the floor to save space.”

But after Britain and France declared war on September 3, 1939, the gold began coming to Canada in earnest. The first wartime shipment involved the light cruisers HMS Emerald and Enterprise, the cruiser Caradoc, and two imposing R-class battleships, the Revenge and the Resolution. Each would comfortably carry £2 million in gold bars.

Although especially foul weather made the convoy’s crossing hazardous, it also served to minimize the potential for enemy attack. The ships arrived without incident in Halifax on October 16.

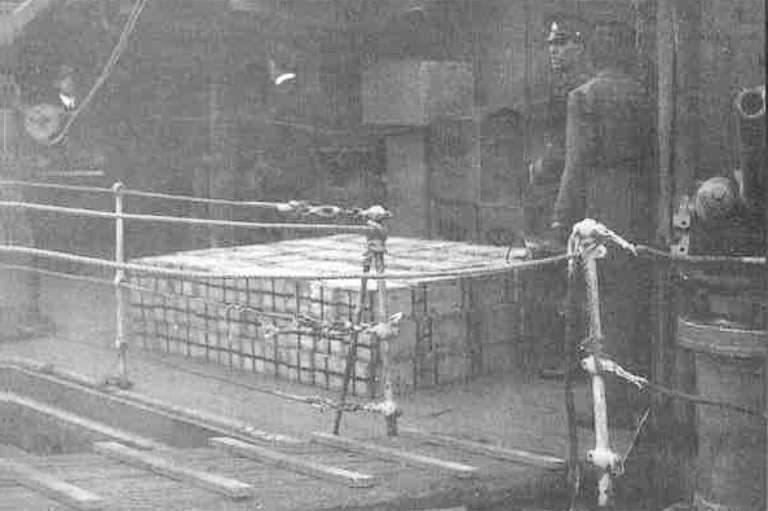

It is notable that the arrival of gold in Halifax and its subsequent transfer to waiting trains was conducted in such secrecy that the Maritime Command Museum in Halifax holds no record of any dockside, gold-related activity. Even the file on HMCS Assiniboine is devoid of any reference to gold transfer, despite British records clearly showing it to have carried £1 million from Plymouth to Halifax in November 1939.

Museum director Marilyn Gurney offers that Pier 6, a nondescript cargo pier at the foot of Ross Street, would likely have been used for the transfer of gold from ship to train.

“The rail line runs right by it,” she says. “The ship could come alongside undetected, and the cargo offloaded, without raising suspicion, onto the train, which would then travel the direct line to Montreal. No one would be the wiser, as this activity would blend in with the normal work environment.”

British records, based on Admiralty papers and personal interviews with ships’ captains conducted years later, paint a clearer picture of dockside procedure.

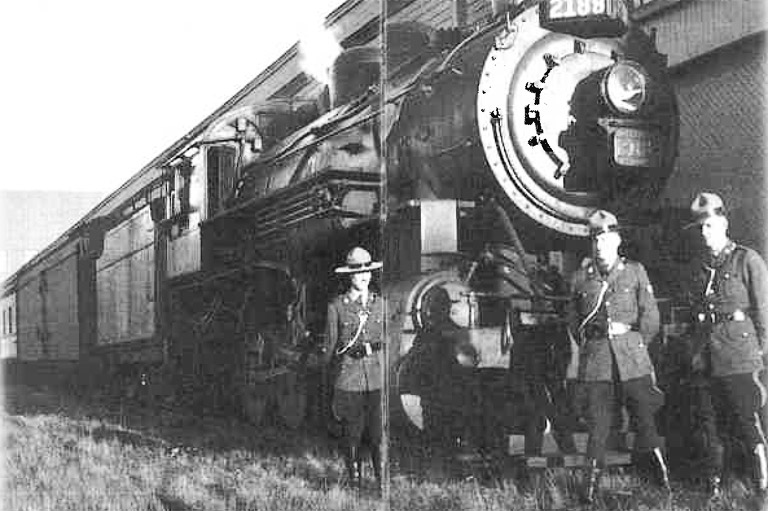

“No entry was made in the log book of the hundred or more Canadian Mounted Police standing guard by the side of a goods train already waiting with steam up on the quayside,” Alfred Draper wrote in Operation Fish: The Race to Save Europe’s Wealth 1939-1945.

“Apart from the Mounties, there was not a soul in sight. ... As the boxes reached the upper deck each was individually checked before being put aboard trolleys and trundled ashore. Before the crates were loaded into the wagons they were again checked by a senior official of the Bank of Canada.”

By mid-1940 Britain had significantly stepped up the campaign to deliver its treasure to Canada for trade and safekeeping. In the final days of France’s struggle against the unrelenting German regime, Winston Churchill became Britain’s prime minister.

While he trumpeted publicly about Britain’s finest hour and never surrendering, privately he began making arrangements to evacuate to a secret deposit in Montreal not only the remainder of the country’s gold, but also the foreign securities holdings of private individuals and businesses. Even as citizens heeded the call to turn in their securities to the Bank of England for safekeeping, Churchill, unbeknown to them, was making arrangements to transfer the mountain of paper to Canada.

Both the gold and securities must be delivered safely across the Atlantic, he knew, for without them Britain would have had nothing with which to continue underwriting the exacting cost of war. Although Churchill was actively negotiating a lend-lease arrangement with America, his supplier of war material (an arrangement that would not come about until the following year), the Americans, in 1940, were unrelenting in their need to see goods exchanged for cash. Without its treasure stowed safely in Canada, Britain's defeat was imminent. Urgency suddenly prevailed.

Previously enforced weight limits were now thrown to the wind as warships and merchant ships alike were loaded down with boxes and bags of bars and coins, often to the point of causing structural damage. Incredibly, every single gold shipment sent as part of Operation Fish made it safely across the perilous Atlantic.

The Revenge sailed into Halifax Harbour in June 1940 carrying £40 million The SS Antonia and SS Duchess of Liverpool followed with £10 million each. Hot on their heels was the Furious, carrying £20 million. Britain’s War Cabinet made the decision not to inform the War Risk Insurance Office of the shipments, reasoning that if one of the ships sank, the loss could never be compensated anyway.

While [Churchill] trumpeted publicly about Britain’s finest hour and never surrendering, privately he began making arrangements to evacuate not only the remainder of the country’s gold, but also the foreign securities holdings of private individuals and businesses.

The country behind the all-time largest shipment of gold aboard a single carrier was France, which sent a staggering 254 tons of bullion – estimated by the Bank of Canada at $305 million – to Canada in June 1940 on the Emile Bertin, reportedly the fastest cruiser in the world at that time. The Bank of Canada had already received several shipments of French gold without incident, but France’s defeat during Emile Bertin’s transatlantic crossing sealed a different fate for this particular shipment.

The British, who had swiftly taken over France’s military debt as well as assets, ordered the gold off-loaded in Halifax for transport to the Bank of Canada with the intent that it would be used to help finance the Allied cause. The Emile Bertin’s captain, however, preferred to take direction from the hastily formed French Vichy government and defied British orders by slipping out of Halifax and sailing for Martinique.

Although Britain was prepared to fight for the gold, the risk of being seen as an aggressor in the eyes of powerful America was too great a gamble. And so Churchill was forced to let the ship go.

France already had 10,581 bars of gold stored in Ottawa, and now Britain moved to persuade Canada to free the cache so it could serve the Allied cause. Canada saw its role as impartial banker challenged, and after a debate that dragged on for months, decreed that France’s assets in Ottawa would be frozen until the end of the war. According to the government, the time had come for Canada to "distance itself from Britain’s international agenda [and] cease acting out of colonial obedience.”

In the meantime the Emerald had sailed to Halifax carrying Alexander Craig and his record-breaking shipment of British treasure. In mid-July 1940, that shipment was dwarfed when the warships HMS Revenge and Bonaventure, and the former luxury liners Monarch of Bermuda, the SS Sobieski, and SS Batory left for Halifax, carrying among them £192 million in gold bullion and a conservatively estimated several hundred million pounds in foreign securities.

Sidney Perkins of the Bank of Canada, on hand for the convoy’s arrival in Halifax, was astounded when he read the manifests’ figures for the five ships.

“Seeing tens of millions in gold piled on the quay gave me a cold chill,” he told writer Leland Stowe. “Even with the whole area fenced off, some word about this enormous shipment could easily leak out in a big port like Halifax.”

As before, trains were waiting to ferry the cargo to Montreal, where the cars carrying securities would be unloaded and the cars laden with bullion sent on to Ottawa. For this particular shipment, five special trains were required because the floor of each coach could only handle the weight of 150 to 200 boxes.

Locked inside each coach were two guards on four-hour shifts, with around fifty guards in all attached to the convoy, served by their own dining car and two sleeping compartments. The bullion travelled uninsured (no one in wartime would con sider in suring such a vast amount of gold), and the cost of transport charged by Canadian National Express, reportedly over a million dollars, set another record.

Through the safekeeping of tons of bullion with nary a bar misplaced, ... Canada maintained a level-headed leadership role in tlte deliverance of nations more powerful and hundreds of years older.

Britain had previously made arrangements to store the securities at the Sun Life Building in Montreal, at that time the largest commercial building in the Commonwealth. The Emerald was the first to bring securities, and in the early hours of the morning of July 3, through cordoned-off streets, its paper cargo was trucked to the east entrance of the Sun Life building.

Under the watchful eyes of armed police, the boxes were carried down to a temporary repository known as the Buttress Room. Permanent housing in a secure, steel-reinforced concrete vault in the third basement of the Sun Life building, fifteen metres below street level, was to be constructed, but finding the steel, which was in chronically short supply, had proved a problem.

Resolution came in the form of 870 rails pulled up from an abandoned railway and a massive vault door borrowed from the Royal Bank of Canada. Two powerful compressors were set up at street level to blow 360,000 kilograms of sand, cement, stone, and water into the building’s basement. Street-level curiosity was met with vague references to structural weakness in need of bolstering. By July 28 all was ready.

“The vault door,” wrote Joseph Schull in The Century of the Sun: The First Hundred Years of Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, “was in place and in operation, set into steel-ribbed concrete walls three feet thick, and behind the walls were nine hundred four-drawer filing cabinets, all crammed with securities.”

They were protected by an alarm system so delicate that it would record the sliding of a drawer, and they were guarded night and day by twenty-four men of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police who ate and slept in the building.

The RCMP recruits were members of the RCMP Musical Ride, who were training in Rockcliffe, Ontario, when the call came to travel to Montreal. Although other records suggest that the recruits guarded the Sun Life Building’s secured third basement, it is more likely that they stood watch over the unsecured Buttress Room while the secured area was being prepared, which took approximately six weeks.

Retired RCMP Officer Bill Ritchie of Calgary, Alberta, well remembers the adventure.

“On arrival, two members each were stationed at the first and second basement floors at the elevators, while the majority were in the third basement, doing shift duties. We witnessed the arrival of numerous boxes being brought to the third basement while the vault was being constructed, with us standing guard. Still, we did not know officially what they contained.

“We made $1.50 a day and really had a lot of fun. We were a very cohesive group and we bonded a lot during that month and a half, but in the end we were happy to return home.”

When all was ready in the main vault, Alexander Craig hired some 120 retired financiers and quietly declared the United Kingdom Security Deposit open for business. Over the next four years a significant portion of the securities was marketed even though most Sun Life employees elsewhere in the building remained unaware of the nature of the business being conducted in their basement.

Two records mention owners having been reimbursed in sterling for the sale of their stocks. After the war the remaining stocks, severely diminished in volume, were bundled up and returned to Britain on board the HMS Leander. How many were sold to support the war effort remains unknown.

As for the gold in Ottawa, there seems to have been no particular postwar haste on the part of player countries to clear out their Bank of Canada accounts. In fact, all involved kept their Ottawa accounts active, and several went on to increase their balance after the war. Beyond minimal shipping costs, the Bank of Canada imposed no charge for the processing and safekeeping of the 186,332 gold bars and more than 8 million ounces of gold coins received between 1938 and 1945.

Operation Fish was, in many ways, the classic Canadian coming-of-age story. Through the arrival, sorting, and safekeeping of tons of bullion with nary a bar misplaced, and through the organizing of thousands of boxes of unsorted paper with not one treasury bill lost, Canada maintained a level-headed leadership role in the deliverance of nations more powerful and hundreds of years older.

Though the Canadians involved must have ached to spill the bizarre story that indeed was stranger than fiction, secrecy was maintained and trust went unbroken. In the end there were no medals, no recognition, no jubilant fanfare. Only memories, and the enduring knowledge that a most unlikely job had been remarkably well done.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!