Shopping for Victory

In May 1942 the National War Finance Committee placed an advertisement in Maclean’s depicting the disembodied visage of Adolf Hitler whispering into the ear of a woman about to open her purse.

“Go on,” he says.

“Spend it. What's the difference?” It was a message the government had been trying to convey since putting the price ceiling into effect in December: when you go shopping, you go shopping with Hitler.

On the same page, two more advertisements appeared. One was for Koneray brand pleated skirts, imported from Warwickshire, England, and the other for built-to-order summer cottages and cabins, “your own vacation headquarters” available in “easy monthly payments.”

Modern readers may find the contradiction - ads for frivolous consumption side by side with anticonsumerist propaganda - to be very odd, but readers in the spring of 1942 probably did not, having by then learned to take such contradictions in stride.

As one druggist observed later that year, “Inventories are shrinking. Shelves are showing bare spots. Many lines of merchandise are in short supply, and sales are booming.”

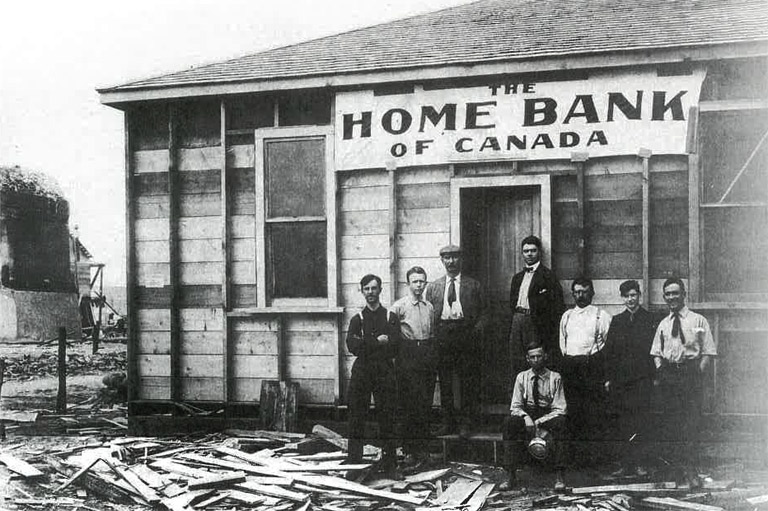

What a strange war it was. While Britons at home felt the shock of war from its earliest days and Americans would after Pearl Harbor, Canada’s “phony war” lasted more than two years — two years when Canadians seemed neither at peace nor fully at war. No one who remembered the Great War could fail to notice the difference.

In April 1915, just nine months after the Great War had begun, the men of the First Canadian Division held the line at Ypres while the Germans mauled them terribly: the division suffered six thousand casualties in three days. But in May 1942 the Second World War was almost three years old and the army had not yet fought the Germans, and apart from one terrible morning at Dieppe that August, would not until another year had passed.

Casualties in the Pacific and in the RCAF had been higher, but were nowhere near the catastrophic losses Canadians had braced themselves for in 1939. Meanwhile, amidst much talk about sacrifice, the reality at home was full employment, higher wages, and a booming retail economy where rationing and shortages had only just begun to pinch.

When the war erupted in September 1939 there had been no calls at all for conservation or thrift. In Maclean’s the editors had expressed a typical sentiment at the time, urging readers to “carry on” – a phrase that had been popular in Britain during the Great War.

Carry on and buy a new car, for instance, since “the best service that can be rendered is to keep our national economic structure functioning as normally as possible.”

A year later, one of the largest voluntary organizations in the country, the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, urged Canadians to “buy victory now,” not with war bonds, but by purchasing British-made goods.

“The clothes you wear, the beverages you drink, the presents you give this Christmas could help win the war. Do you realize that the expenditure of only 50 cents a day on British goods by each Canadian could make a profound difference to Britain’s financial position?”

With the Depression finally over and jobs available for anybody who wanted one, Canadians in the early years of the war had more money than ever and nothing but encouragement to spend. “Money just rolled in,” one man recalled years later. “In the war we lived good. Real good.”

Indeed, “Enjoy life!” was the tag line on a 1940 DeSoto ad, depicting happy passengers in a new sedan, hurtling through the spring, published in Canada even as the British Expeditionary Force was, in Churchill’s phrase, “hurled into the sea” by the Nazi thrust into France. Overseas, the moment of supreme crisis was at hand; in Canada, retail sales were the highest they had been in ten years.

After the fall of France in early 1940, orders from Britain for munitions of all kinds poured in, but for more than a year Canadian manufacturers, so many of whom had been idle through the long lifeless years of the Depression, were able to meet these demands without seriously interrupting the flow of consumer durables.

In fact, the next year would be one of the best ever for the sales of washing machines, stoves, refrigerators, toasters, and other appliances. As late as June 1941, even as the Germans stormed east towards Moscow, the editors of Automotive Trade wrote reassuringly that business could go on as usual, there being no evidence that immediate changes were required.

In the opinion of Mackenzie King’s government, however, immediate changes were required. All economic signs pointed to the beginning of an inflationary cycle. In the Great War runaway inflation had afflicted life on the home front, and King, having promised Canadians a war of “limited liability,” feared the domestic consequences of inflation in this war.

King’s government vested the task of keeping inflation down in one of its most powerful agencies: the Wartime Prices and Trade Board, and its new chairman, Donald Gordon. In the summer of 1942, King personally intervened to release Gordon from his position as deputy governor of the Bank of Canada, and for the remainder of the war Gordon worked tirelessly to regulate the country’s retail economy.

Of all the Ottawa Men — the civil service elite recruited for the duration of the war from the ranks of finance and industry — Gordon became the most visible, his picture looking back from the newspaper almost daily.

“The great tragedy of our time,” he wrote in the first issue of Consumers’ News, the newsletter of the board’s consumer branch, “is that no democracy has been able to understand or to accept the demands of total war until its homes were under actual bombing attack.”

In Gordon’s view, modern war required extreme sacrifices. It meant the subordination of every consumerist whim to the war effort. Every cent not spent on war savings bonds, every yard of fabric that made dresses rather than uniforms, every gallon of gasoline pumped into a passenger car rather than a military truck, materially aided the Axis.

Among Gordon’s first duties was to explain to the public the necessity of putting a ceiling on prices in order to combat inflation.

“You, who are listening to these words,” he said in a radio address on November 28, 1941, “will be going into the fight next Monday ... and make no mistake, you will be on one side or on the other. In this fight against inflation you cannot be a neutral. You will either be helping to save yourself, your family and your country from a terribly calamity — or you will be working for the enemy.”

Monday was December l, 1941. On Sunday, December 7, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Perhaps that was the week that Canadians on the home front really went to war. Only then, as the war assumed global proportions, as procurement orders from Britain intensified, and as the American economy began its astonishingly rapid conversion to military production, did Canadians begin to experience the full impact of the total mobilization of their economy for war.

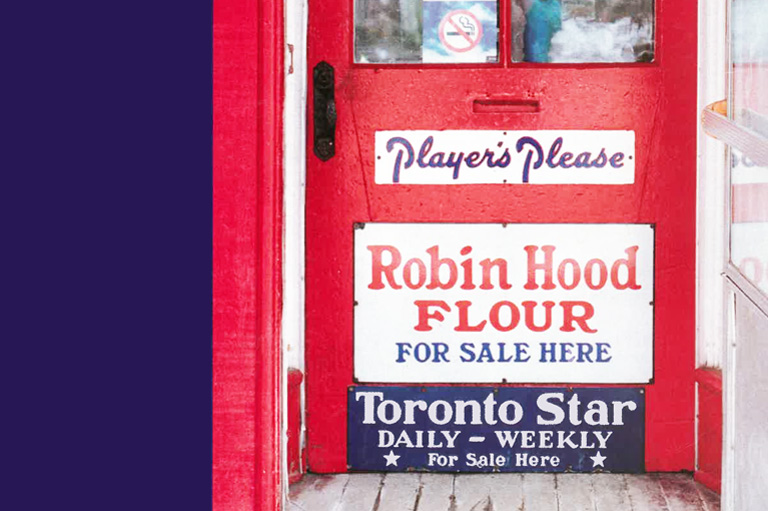

Production of electric refrigerators plummeted from an all-time high of 64,000 in 1941 to 350 by 1943, while the number of home radios produced dropped from half a million in 1940 to none in 1944. Of course the most striking difference was the almost total absence of new passenger-car production after 1941. Canadians bought 300,000 new cars in the first three years of the war.

In 1943 they bought about 900, and those were strictly reserved for civilians with essential needs. In addition the government instituted coupon rationing for sugar, coffee, and tea in the summer of 1942, butter later that year, and meat in May 1943.

Canadians did not respond to the board’s regulations as enthusiastically as is sometimes supposed. Officers of the board’s consumer branch, a nationwide organization of women dedicated to monitoring the price ceiling, endured incessant complaints from consumers about the price and quality of goods (one officer summed it up by defining a “sissy” as someone “who resigns from the WPTB Committee to join the Commandos”) and the board investigated thousands of businesses for violating the price ceiling.

Against express rules, people bartered, sold, raffled, and made gifts of their ration coupons; they hoarded goods, bought from black markets, or took advantage of the “grey market” (where a friendly retailer might, for instance, keep scarce goods under the counter for customers willing to pay a little more), and a man in Toronto was fined $100 because he managed to get a ration card for his dog.

However, even where rationing regulations were obeyed, they did not hurt much. Coffee and tea rations, for instance, permitted everyone over age twelve enough for about ten to twelve cups of each per week, and there was nothing to stop anyone from getting an extra cup (although no more than one per sitting) at one of the country’s proliferating diners and restaurants, whose business tripled during the war.

Butter and sugar rations permitted half a pound per person per week, and only in rural areas when canning season came around were there many complaints about the quantity of sugar. In the summer of 1943, in order to meet export demands for the U.K., the government introduced meat rationing at home, but this was intended to reduce individual consumption by just 15 to 20 percent. Even gasoline rations at their tightest never seemed intolerable, permitting most drivers 455 litres per year, enough for more than 3,200 kilometres of driving.

Nor was the rest of the retail economy as tight as we sometimes remember. Even as Canadian war production soared to levels that no one in 1939 could have ever imagined, Canadians found plenty of reasons to spend as well as save.

Retail spending increased in 1942, as it had every year since the war began. It rose again in 1943 and in 1944. By the time the war ended in 1945, Canadian consumers were spending 50 percent more than they had been six years earlier, even after accounting for inflation.

After 1941 new durables like cars and appliances were nearly impossible to get, but the fact that retail sales continued to rise indicates how intensely consumers spent on the narrower range of goods that were still available.

Over the course of the war, restaurant business tripled; jewellery, women’s clothing, shoe, and drugstore sales doubled; and paid admission in movie theatres leapt to 208 million in 1944 from 138 million in 1939.

Between rationing, shortages, and government pressure discouraging spending, how did consumerism not just survive, but also sometimes even prosper during the war?

Not surprisingly, manufacturers responded to the world crisis with an avalanche of war-themed products, ranging from sensible gifts such as shaving kits and watches for servicemen to the truly bizarre and downright tacky (“V for Victory” haircuts and “Patriot Pads” for women).

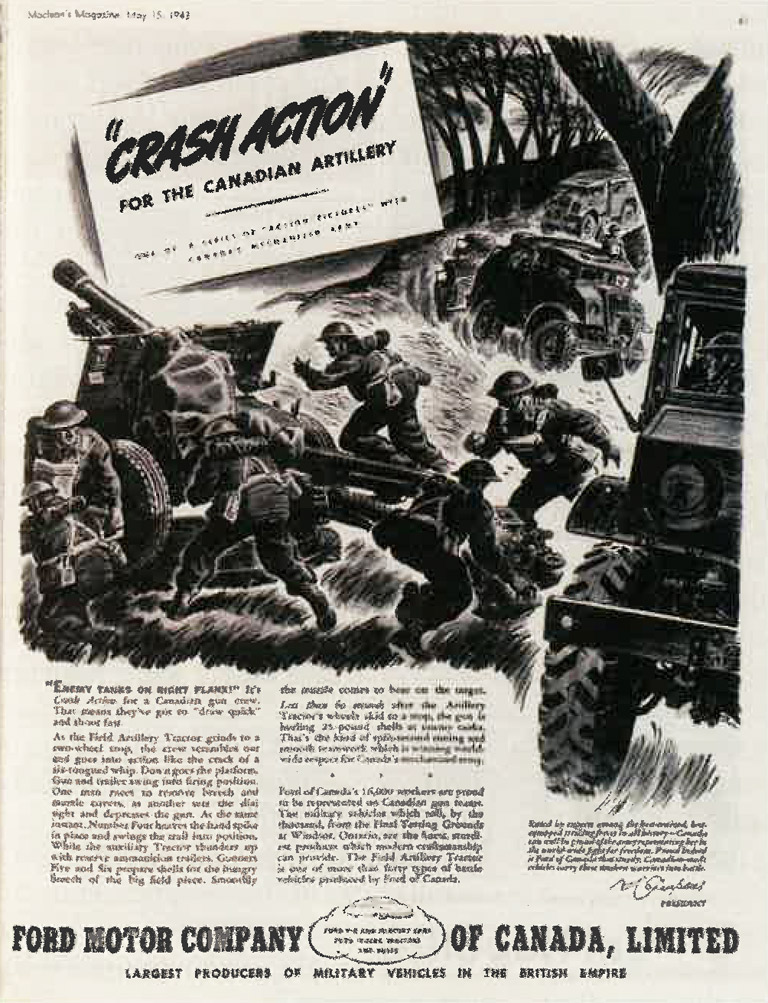

Advertisers were particularly ingenious about devising ways of encouraging patriotic shoppers to part with their paycheques, stressing that buying their particular product was neither wasteful nor unpatriotic, but a contribution to the war effort, even a sacrifice that consumers made for freedom.

“Your hands now need Campana’s balm more than ever,” reads a typical ad, depicting a woman hunched over a machine tool in one corner and accepting candy from a gentleman caller in the other. Phrases like “now more than ever” became the stock and trade of wartime advertising: one needed the special properties of consumer goods even more urgently in wartime than in peace.

For every government ad urging conservation and thrift, there were dozens more insisting that spending rather than saving was the most important contribution a person could make to the war effort.

When they had nothing to sell to the public, manufacturers such as General Motors and Ford responded with imaginative “goodwill” advertising, emphasizing their enormous contributions to the war effort. As victory grew closer, advertisers began to depict a world of the future where the technical ingenuity unleashed by the war would be transformed into astonishing new consumer goods.

Like advertisers, retailers evaded accusations of wastefulness by arguing that they performed duties essential to a nation at war.

Restaurants and grocers kept war workers in the pink with good, nutritious food, while druggists did it with pills and potions. Beauty parlours and jewellers maintained morale. Booksellers kept the public informed. Stationers provided for the smooth operating efficiency of the nation’s bureaucracy.

While the Wartime Prices and Trade Board stressed that consumers must buy only what they need, many retailers attacked the notion that moderate consumption was harmful.

One ad copy read that “sane” conservation was “useful patriotism,” implying that there was an insane variety that was not. A writer for Canadian Jeweller mused that he could make a “tidy sum” with a series of articles suggesting that war bonds be exchanged in place of engagement rings, but he wondered how far such trends were likely to go. Would the public be persuaded that buying luxuries is unpatriotic?

“Man lives by certain civilizing influences,” he warned. “These include the luxuries of the daily newspaper, art galleries, and fine pictures; music and theatrical entertainment; movie shows; and rapid transit, motor cars, airplanes, time saving appliances, even a knife, a spoon, a few serving plates, an ornament or two for various parts of the house. We must not permit the public to forget jewellery ... to have a good heart for war work, people must have something extremely desirable to fight for,” by which he meant access to luxurious commodities.

This became a central theme of advertising late in the war: the equation of consumer choice with political freedom. One advertisement in a trade journal urged Canadians to fight harder for the “pleasures of freedom,” pleasures depicted as a deluge of consumer goods.

One after another, advertisements argued that what made Canada superior to the Nazi slave state was the material wealth its citizens enjoyed, and that this, too, was one of the things for which the war was being fought.

“Next to winning the war and the peace, our greatest responsibility is to preserve our Canadian way of life which revolves around the system of initiative and enterprise,” wrote the editors of Drug Merchandising, a retail trade journal, or, as one advertisement in Maclean’s, referring to the “four freedoms” of the Atlantic Charter put it: “four freedoms aren’t enough!”

An essential fifth freedom, the freedom of free enterprise, must also be defended.

“So let’s boil it all down to this,” the ad reads, “the right of free choice ... to choose our opinions and our words, our religion, our homes, our clothes, our books and breakfast foods, friends, and amusement.”

In short, the war against Nazi fascism was much more than a struggle for political democracy: it was a struggle for a way of life in which mass consumerism played a crucial role.

In postwar mythology, the mystique of home-front sacrifice holds an exalted position. We remember how Canadians at home pulled together, worked longer hours, endured rationing and shortages, collected scrap and fats and bones, bought only war bonds, and sacrificed everything else to share the burden with the boys overseas.

But the reality of the home front, of a booming consumer economy for the first half of the war and a surprisingly vibrant one for the second, of restaurants, clubs, and cinemas full to capacity throughout, sits uneasily beside the more patriotic image of self-sacrificing civilians.

Or was it possible to make sacrifices in the realm of consumption? Canadians had never enjoyed an era of guiltless mass consumption; their consumption had always been moderated by a variety of economic and social concerns about the things they bought.

But by the 1940s, consumerism was nonetheless an important part of Canadians’ everyday lives, and their consumerist impulses were highly developed indeed. Women in particular had long since assumed the duties of primary consumer for the household (one 1939 advertisement depicted a woman in her bridal gown under the words “Purchasing Agent — just appointed”) and they accounted for 85 percent of retail spending.

After the Great War, annual Armistice Day1 ceremonies and the thousands of war memorials erected in every city and town in Canada imbued Canadians with a profound sense of the inherent nobility of sacrifice, and a belief that the willingness to sacrifice was the measure of loyalty to one’s country.

On the home front, however, sacrifice could mean many things, from separation from a husband or son to working in a munitions plant. But it could also mean having to cope without a replacement for a refrigerator on the fritz, and indeed having to make the difficult choice between buying a war bond or buying a consumer product that advertisers sensibly argued was also a contribution to the war effort.

Canadians surged forward to fight the Second World War in a thousand ways. Perhaps it should not surprise us that for many people on the home front much of the war, and much of their war effort, seemed to have a great deal to do with being a consumer.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!