Daredevils

A crowd of ten thousand watched as a coffin was lowered into the Red River in Winnipeg on October 30, 1983. Inside was nineteen-year-old escape artist Dean Gunnarson, his wrists handcuffed and his ankles shackled. Gunnarson was attempting his most daring stunt yet: an escape from a submerged coffin that was nailed shut and wrapped with chains.

He could hold his breath for two, perhaps two and a half minutes, which he thought would be plenty of time to make the escape. But something went wrong. As the coffin hit the river and Gunnarson took a final deep breath, the coffin didn’t fill up with water and sink as planned.

An air pocket formed in the chamber, so Gunnarson exhaled his air once more. But this time the coffin went under, without Gunnarson having taken in enough air to allow him to complete his escape.

It’s advantageous when time goes by slowly while performing an escape — you get more done in what feels like less time. But this was different. Trapped underwater in a coffin, his lungs filling with water, Gunnarson knew that more time in the river was not to his advantage.

He realized that if he panicked he would die. He abandoned the escape and focused on surviving. He put his hands to his goggles, relaxed, and went into a meditative state.

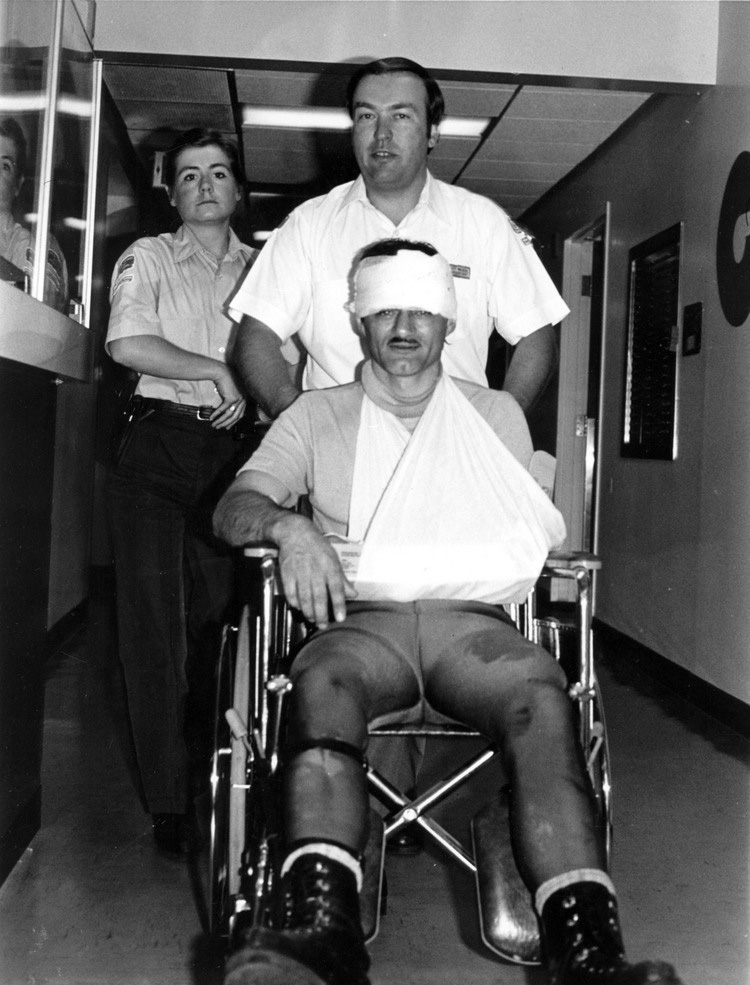

After about four minutes, the coffin was pulled to the surface. Inside was Gunnarson, unconscious, his skin blue, deprived of oxygen to the point that a medical chart would have said he was dead. Indeed, he later described seeing a tunnel and a light before he was revived.

When he regained consciousness in the ambulance, he was unable to open his eyes, but the sirens told him what was happening. He later woke up again in the intensive care unit at a hospital with his family surrounding him and everyone “freaking out,” he remembered.

Gunnarson didn’t understand their concern at the time — from the start, he was confident he was going to live. It wasn’t until he saw footage of his failed escape, with his blue and unresponsive body being pulled out of the coffin, that he realized how terrifying the whole experience was.

That cool October day could have been Gunnarson’s last — the escape attempt could have killed him, or it could have scared him from performing daredevil stunts ever again. Neither happened.

“Failure in itself is just a learning experience,” he said later. Gunnarson refined the execution of the stunt, including by improving communication between himself and the surface-level team.

Undaunted by his near-death experience, in 2014 in The Bahamas he climbed into a metal coffin submerged in water. Not only did he have to escape confinement, he also had to evade the hundreds of sharks circling him.

Escape Artists

Dean Gunnarson says he has been inspired by many daredevils throughout history, such as the legendary Harry Houdini and Thomas William Hunt, or The Great Farini, who was born in New York State but moved to Ontario with his family when he was young.

In 1860 The Great Farini hung over Niagara Falls, dangling from a tightrope by his toes. The stunt inspired Gunnarson, nearly 140 years later, to hang over Nevada’s Hoover Dam by his toes while escaping from a straitjacket.

Why put your life on the line for the sake of a cheering audience?

Daredevils evolved from more tame public performances, explains sports historian Kevin Wamsley of St. Francis Xavier University in Antigonish, Nova Scotia. Spectator entertainment — theatre, strength competitions, public fighting — was a popular form of amusement in the nineteenth century. The riskier the activity, the more excitement it generated.

It takes a particular type of person to tackle such daring acts.

Gunnarson, now fifty-five, says he’s known since he was very young that he didn’t want to be an ordinary person — unlike classmates who constantly tried to fit in with different groups.

“I never wanted to be like anyone else,” he said. “I wanted to be me.” He notes that daredevils throughout history, from escape artists like him to those who tested themselves against Niagara Falls or a narrow tightrope, don’t quite seem to fit the norm.

Perhaps the drive to be different is reason enough to attempt what most people would find peculiar, even unthinkable. Or perhaps the rush of adrenaline — the ultimate high — or genetics also played a part.

Cynthia Thomson, a researcher at the University of the Fraser Valley in Chilliwack, B.C., has found that athletes willing to take risks were more likely to have the same genetic variance in a dopamine receptor.

Dopamine is a chemical with a variety of functions, including signalling the body to move and encouraging people to seek reward through something that gives them pleasure, whether an achievement or a moment of excitement. Thomson’s research has not yet shown exactly what the variation does, but she says there is a difference between thrill-seekers and those who’d rather play it safe.

Thomson emphasizes that, while her research is consistent with other studies on risktaking, additional factors such as personality, which is affected by both genetics and environment, can also influence someone’s propensity to be a daredevil.

Regardless of their motivation, people have been performing outrageous stunts for centuries. While modern-day risktakers can edit their escapades before posting them online, their plucky predecessors had no such luxury.

Daredevils in early Canada often had one chance to get it right — and risked life and limb to thrill their audiences.

Barrel Riders

The ground rumbles as you approach Horseshoe Falls, the Canadian section of the three cataracts that form Niagara Falls. Water rushes down the fifty-seven-metre cliff at sixty-five kilometres per hour, the mist from the almost-deafening churning water drenching tourists who visit this magnificent natural wonder.

Niagara Falls can take your breath away … and it can also take away your life.

Since the 1800s, several people have gone up against the falls, attempting to show their strength, determination, and apparent lack of fear. They’ve dived into the falls, walked across them on a tightrope, and hurtled over them in a barrel.

The barrel trend started in 1901, when sixty-three-year-old Annie Taylor, born in New York State, climbed into an oak barrel stuffed with padding. The barrel was released into the Niagara River, and Taylor floated toward the Horseshoe Falls.

After twenty minutes, over the falls she went, and after another twenty minutes rescuers retrieved her barrel. They cut the lid open to find Taylor alive and in relatively good shape, besides some bruises and a cut on her head.

“No one ought ever do that again,” Taylor declared to the gathered crowd.

In the December 5, 1901, edition of the Detroit Free Press, she explained that she chose to go over the Horseshoe Falls, instead of the American Falls, so she wouldn’t be “dashed to pieces on the rocks.” Taylor said she did the stunt because she needed money, though fortune never came her way. After a blink of fame, she ended up living in poverty and died in 1921.

After Taylor, several more people went over the falls in a barrel and lived. But others did not have the same luck, including Charles Stephens, a fifty-eight-year-old barber from England.

On July 11, 1920, he climbed into a wooden barrel and had his arms strapped inside. There was an anvil at his feet to help him steer. Stephens and his barrel floated in the river for five kilometres before reaching the edge of the falls.

After the drop, the barrel was recovered, and the only thing inside was his right arm. The anvil at his feet went through the bottom, taking his body with it.

Karel Soucek was the first Canadian to go over the falls in a barrel. Born in what was then Czechoslovakia, Soucek earned Canadian citizenship and lived in Ontario. He was experienced in daring feats involving the falls. He had attempted, but failed, to cross the Whirlpool Rapids (downstream of Niagara Falls) while riding a moped on a cable — a harness saved his life — and he also went through the same rapids in a steel barrel.

Soucek challenged nature again in 1984, attempting to go over the Horseshoe Falls in a wooden barrel he had designed. Twenty-three years after the previous person had attempted the feat, he survived the drop with minor injuries and was fined five hundred dollars for performing his stunt without a licence.

Six months later, Soucek attempted to recreate the act at the Houston Astrodome in Texas in front of an audience of thirty-five thousand people. The goal was to drop from the top of the stadium into a water tank below, but the barrel hit the edge of the tank.

Soucek died in hospital from the injuries he sustained. He is buried in Drummond Hill Cemetery, just a few kilometres from the Horseshoe Falls. His gravestone is inscribed with his own words: “It is better for a person to take chance from life … than to live in that gray twilight and not know victory nor defeat.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Strongmen

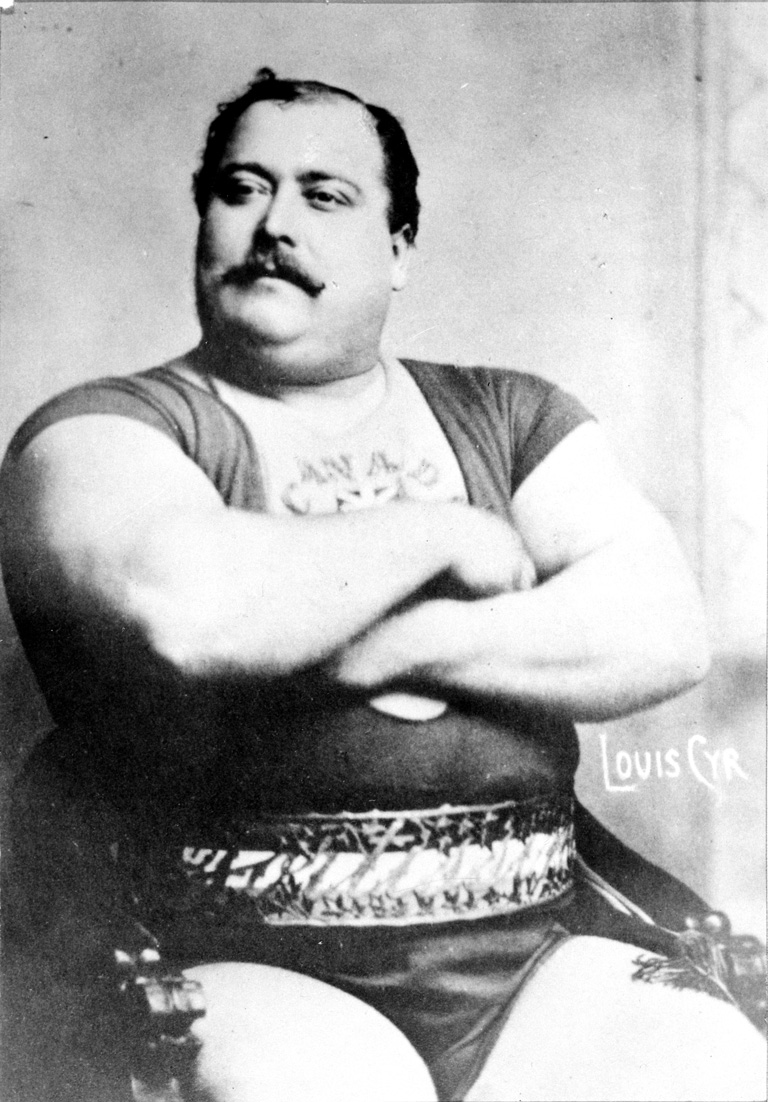

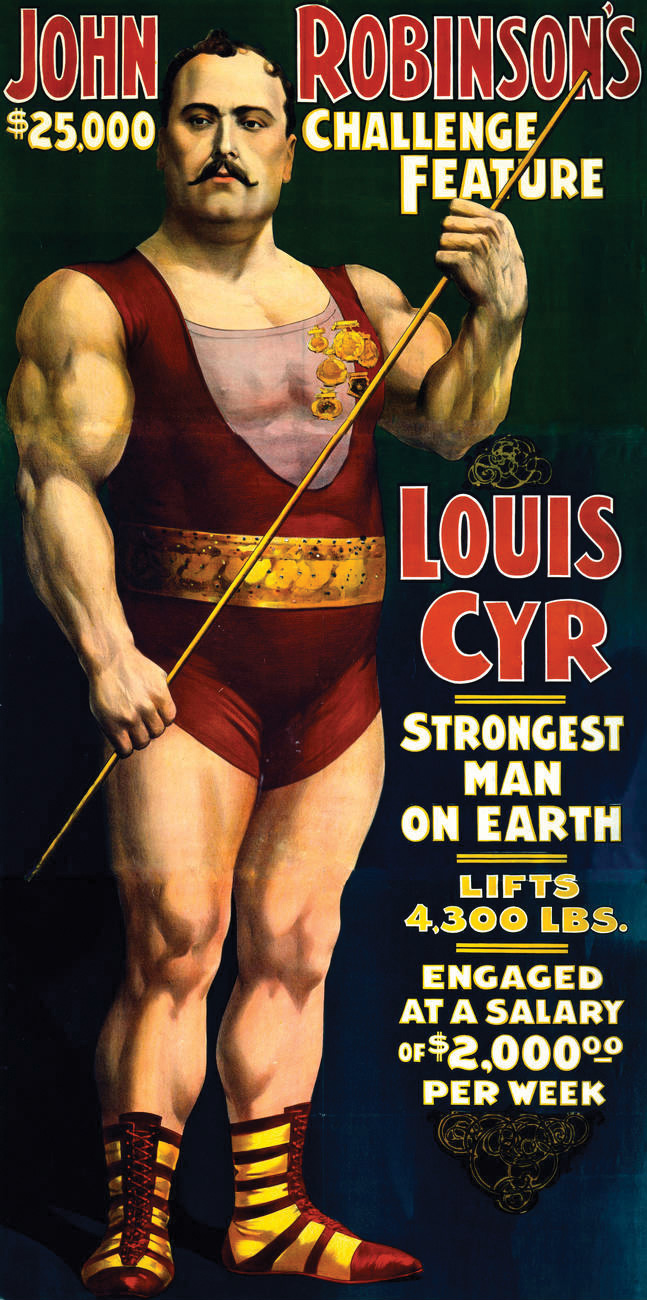

Louis Cyr had his arms strapped to four horses, each animal weighing more than five hundred kilograms. The horses were whipped, encouraging them to run.

Cyr could have had his body torn apart — in front of an audience — or he could prove that he truly deserved the title of “the strongest man in the world.” He achieved the latter.

Born Cyprien-Noé Cyr in 1863 in St-Cyprien-de- Napierville, Quebec, Cyr began entering strength competitions as a teenager, and his talent soon attracted crowds. Weighing 144 kilograms (317 pounds), Cyr could lift 250 kilograms (550 pounds) with one finger; he could hold a platform on which eighteen men stood, weighing a total of 1,967 kilograms (4,336 pounds); and he could deadlift 820 kilograms (1,808 pounds) without bending his knees.

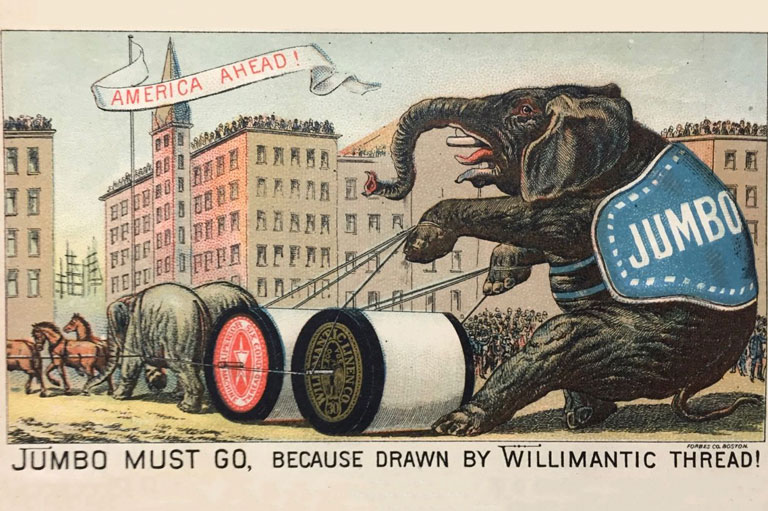

Cyr toured the United States and Canada with circuses, including the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus.

A newspaper advertisement in the April 18, 1886, edition of Michigan’s Marquette Daily Mining Journal advertised an open challenge with a prize of one thousand dollars for “anyone who will duplicate their wonderful feats of strength.”

The reference was to Louis and his brother Peter. In The Cyr Brothers’ Great Show, Louis’s eight-year-old daughter, Émiliana, would lift 45 kilograms (99 pounds) with one finger and 333 kilograms (734 pounds) with her hands.

But Cyr neglected his health. “He definitely had a kind of strange obsession with putting incredible amounts of food into his body,” says sports historian David Chapman in Historica Canada’s documentary about the strongman. Cyr became obese.

One morning, he woke up with a temporary loss of feeling from his waist down. His deteriorating health has been linked to Bright’s disease, an inflammation of the kidneys.

After taking five years off due to his poor health, Cyr returned for a final strength competition in 1906 in Montreal. Forty-two years old by then, he went up against twenty-six-year-old Hector Décarie.

Cyr didn’t officially lose his title of strongest man in the world — he won some matches that day and lost others — but he did announce his retirement from weightlifting. Only six years later, on November 10, 1912, Cyr died of kidney failure.

Horse Divers

Jumping off a twelve-metre-high tower into a pool no more than three metres deep is a pretty frightening thought on its own. Now imagine doing it while riding a horse.

Anna Chevallier and her horse Johnny entertained crowds in the 1920s and 1930s as part of William F. “Doc” Carver’s crew. An American dentist turned marksman, Carver is credited with creating this act.

Born in Red Deer, Alberta, Chevallier moved to Alhambra, Alberta, before leaving for Chicago, where she worked in a restaurant. She answered an advertisement for women to perform the horse-diving stunt. Chevallier and Johnny made the cut, and they toured with the other divers throughout Canada and the United States.

There was a formula for the stunt: The horse would walk up a ramp to the top of the tower, where the rider — usually a young woman — would be standing on a railing to get her to the same height as the horse.

As the horse passed the rider, she’d jump on, and they’d continue to the edge of the tower.

The horse would step off the edge, sliding down a nearly vertical board a few metres long before taking a leap into the pool. After a giant splash, the horse emerged and quickly walked to the ramp or to the shallow end of the pool.

Even though this act revolved around jumping into water a couple of times a day, Chevallier couldn’t swim. For the most part, this wasn’t a problem; but one time she did fall off her horse into the water. Thankfully, a man — whom she later married — jumped in to rescue her.

Horse diving — either the horse by itself or with a rider — was a popular attraction at North American carnivals and travelling shows from the late 1800s, when the first jump entertained crowds.

For many years, a travelling show brought a pair of horses, named King and Queen, to the amusement park on Toronto’s Hanlan’s Point, where crowds watched the riderless horses plunge into Lake Ontario.

The pastime was already in decline by the time animal rights groups mounted successful campaigns against it in the 1970s.

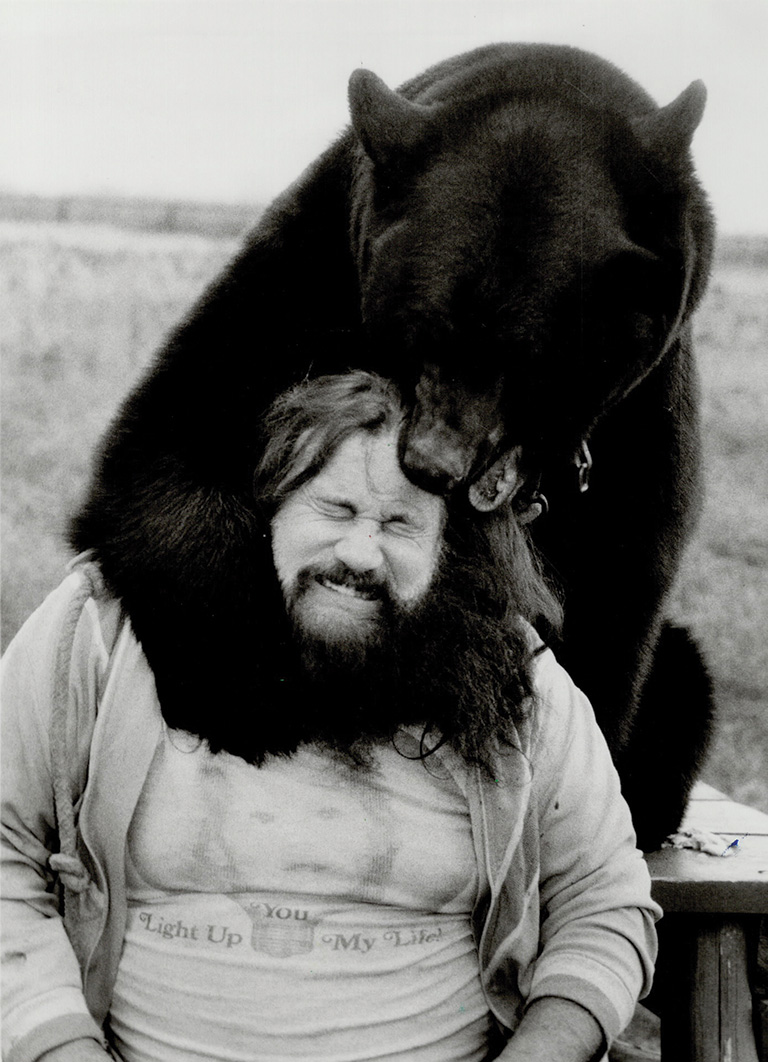

Bear Wrestlers

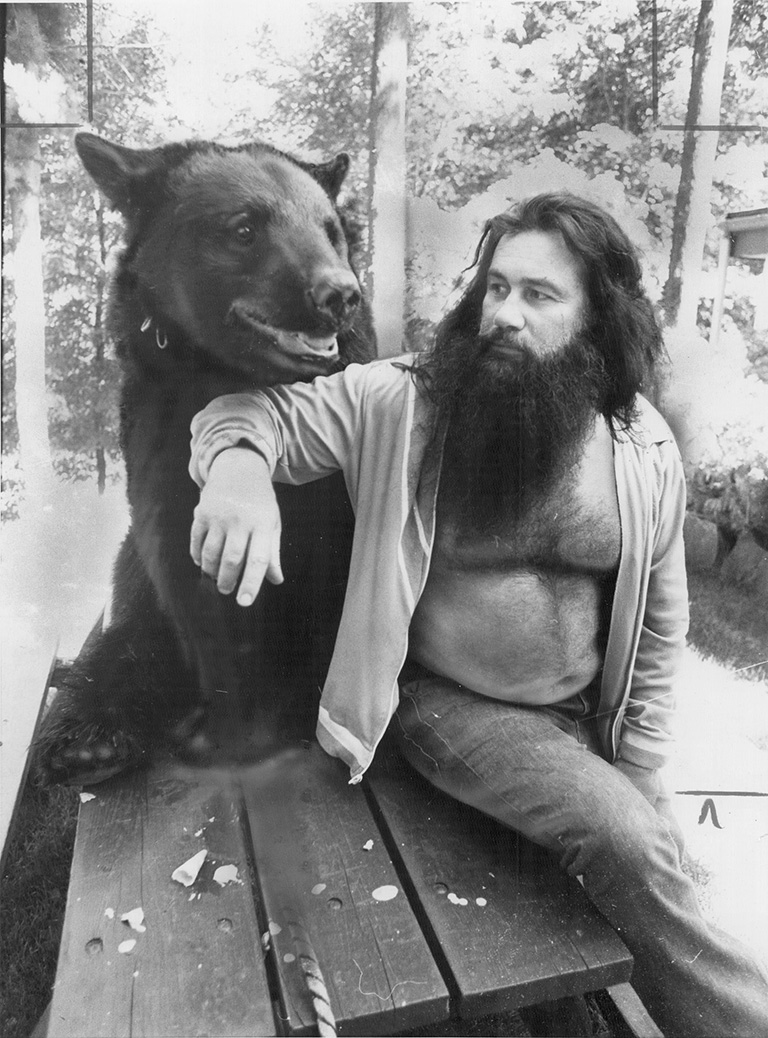

Thousands gather at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens, smoke filling the air as audience members puff on their cigarettes. It’s January 13, 1959, and the crowd is here for a night of wrestling.

Bob McGrath, a CBC Radio announcer, speaks to fans at home: “Now the climax of tonight’s card: the bout between Terrible Ted, the four-hundred-pound black bear, and Bunny Dunlop, another big heavyweight but not quite as heavy as the bear — and without the fur.”

The crowd cheers as the bear and Dunlop, a human being who usually referees matches, enter the ring. As Terrible Ted climbs through the ropes, a man jumps up and pokes the bear. Ted swipes the man, chasing him into the crowd. Fans start running in every direction, scattering to get out of the way. Finally, Ted’s owner-trainer brings the bear back into the ring.

McGrath tries to read Dunlop’s lips. It appears that he’s asking if the bear will bite or claw him; but the owner reassures him that he’s safe — “although he certainly doesn’t look it to me,” the announcer says.

The match begins.

The bear, his owner holding him on a chain leash, stands on his hind legs, and the two wrestlers lay their hands — paws? — on each other. “They seem to be waltzing around there,” McGrath notes.

Each goes for a neck hold, but Dunlop ends up on the ground. He stands up. The two combatants circle each other. Dunlop gets Ted in a neck hold, but the bear shakes his head, freeing himself. He chases Dunlop around the ring and then sits, yawning and apparently bored with the whole thing. The crowd erupts in cheers and laughter.

The match ends with Dunlop exiting the ring and Ted in pursuit, pulling his owner behind him. The referee calls the match a draw, since both wrestlers left the ring.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Terrible Ted, a black bear, made his wrestling debut in 1950. He weighed 272 kilograms (600 pounds) and stood more than two metres (six and a half feet) tall.

Ted’s first owner and trainer was David McKigney, a wrestler from Toronto who fought under the names Gene DuBois, the Wildman, the Bearman, and the Canadian Wildman. McKigney had the bear’s claws cut short and his teeth removed and fed him only vegetables.

But Ted was still a bear, a powerful animal that would swat at, chase, and bite his opponents.

McKigney trained Ted every day and set up matches between the bear and human opponents all over Canada and the United States, sometimes offering cash prizes to anyone who could pin Ted.

Black bears have a lifespan of ten to thirty years, but Ted’s wrestling career was about forty years — so it’s likely there was more than one Terrible Ted.

Bear wrestling was popular from the 1950s through to the 1970s. It added novelty to a regular night of wrestling, and it drew in crowds. But, unlike their human opponents, the wrestling bears didn’t have the choice of whether or not to go in the ring, and this becomes evident when watching videos of such matches.

In a bout between Ted and McKigney, the bear paces anxiously around the ring, reacting only when attacked by the trainer, who at times pushes the referee into the bear. As with horse diving, animal rights organizations pushed to end bear wrestling, although a bear named Sampson is reported to have been involved in wrestling matches in Canada as recently as the 1980s.

Tightrope Walkers

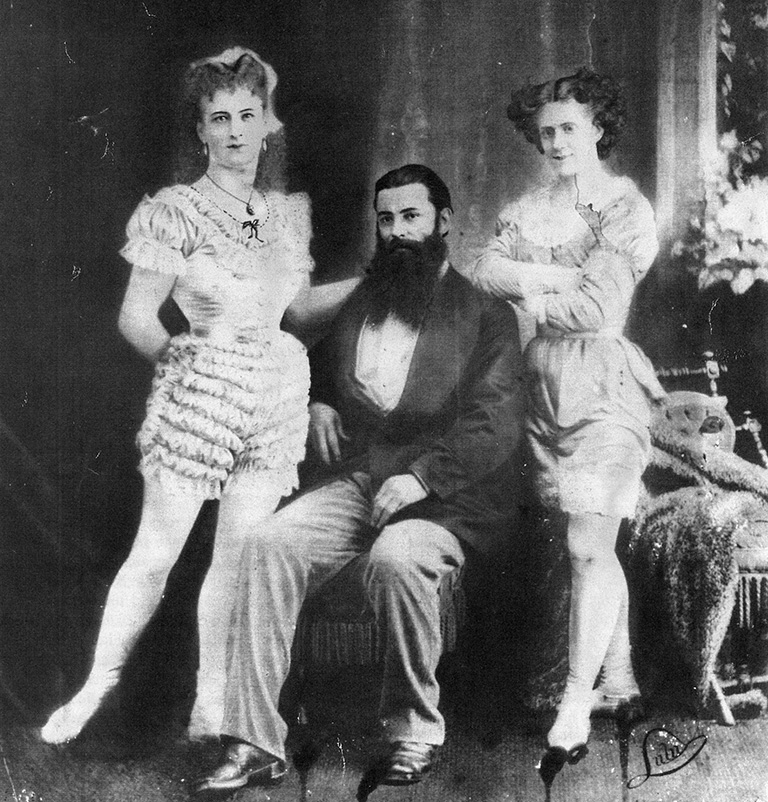

August 15, 1860, was The Great Farini’s day to prove his talent and to risk his life — his big chance to outshine The Great Blondin (Jean Francois Gravelet), who had walked across Niagara Falls on a tightrope the previous year, becoming the first person to do so.

Twenty-two-year-old Farini was born William Leonard Hunt; he later changed his name to Signor Guillermo Antonio Farini. Originally from Lockport, New York, he moved at age five with his Canadian parents to the area around what is now Port Hope, Ontario.

From a young age, he was interested in athletics — he was a talented swimmer — and loved acrobatics, but his parents didn’t support his dream of performing with a circus. Hunt persisted.

At twenty-one, he walked across Ontario’s Ganaraska River on a tightrope. Not only did he manage the feat without using a pole for balance, he even took a break from his walk to do a headstand on the tightrope.

Farini wanted to make his crossing of Niagara Falls more impressive than The Great Blondin’s, so he used a tightrope that was about 550 metres long, nearly twice the length of Blondin’s. The Great Farini was an entertainer through and through. He walked across the falls twice that day — once with a balancing pole and once without one.

An August 20 account in the New York Times described Farini stopping halfway across the tightrope to lower himself by a rope to a boat far below. He is said to have shared a glass of wine with the passengers on board before climbing up to resume his tightrope crossing.

Farini’s daring feat was the start of a continuing game of one-upmanship between himself and Blondin.

After his first walk, Farini continued to perform over Niagara Falls, as did Blondin, with each man adding new and daring elements to taunt the other. Blondin cooked an omelette. Farini washed handkerchiefs in a washing machine he carried with him. Blondin wore a sack over his arms and legs; Farini wore one that went over his feet. Farini also repeated his trick of doing a headstand on the rope.

“Blondin made everything he did look easy, but Farini’s performances were a torment to watch,” writes Ginger Strand in the book Inventing Niagara. “His slack rope pitched and swayed and his tricks pushed his abilities to the limit. He often had to stop and lie down to rest, and frequently caught himself from falling.”

Though Farini saw considerable success, he also dealt with tragedy.

In 1862 in Havana, in front of a crowd of thirty thousand people, Farini walked across a tightrope with his wife, Mary Osbourne, holding on to his back. As they neared the end of the rope, Osbourne took one arm off Farini and waved to the crowd, but she lost her balance. Farini somehow managed to grab her dress, but he was unable to pull her to safety before the fabric ripped and she fell to her death.

Farini tried to perform a few times soon after his wife’s death, but he needed a break to recover from the tragedy.

When he resumed, he continued to wow crowds across the world. This included performances with his adopted son, acrobat Samuel Wasgate (there are several variations on the spelling of his last name) — known as El Niño and later as Lulu — as well as exhibitions with sideshow entertainers.

Farini lived an eventful life as a performer, an inventor (he created the first “human cannon”), an author, and, above all, an entertainer who pushed limits. He died from influenza at age ninety in Port Hope.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.