Jumbo in the New World

On the evening of September 15, 1885, a Northern Trunk freight train crossed Arthur Street in downtown St. Thomas, Ontario, and struck and killed a large elephant. This was not the sort of elephant usually found in St. Thomas, not even on nights when the circus passed through.

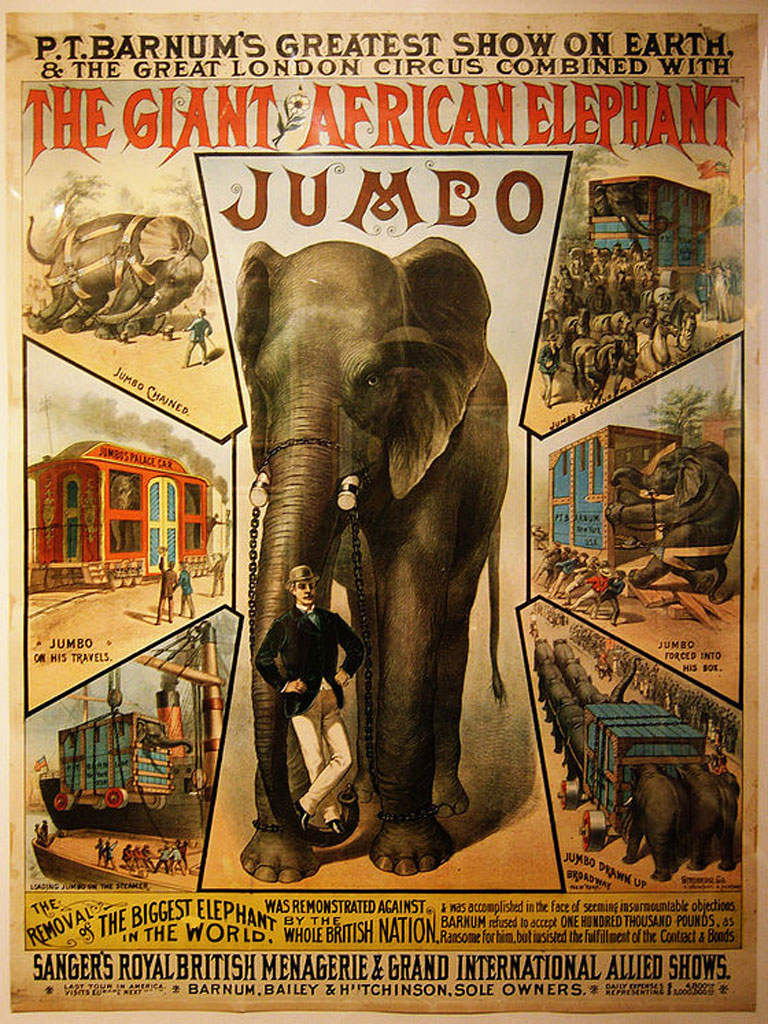

This was the most celebrated animal on the face of the earth — the one creature, with the exception of Mickey Mouse, to have its name canonized in dictionaries of the English language. This particular elephant was Jumbo, backbone of P.T. Barnum’s “Greatest Show on Earth,” and star of the most remarkable freak show to pitch a tent on Canadian soil.

From the outset, the story of elephants in the New World is an unhappy one. The first elephant to reach these shores was the Crowninshield Elephant, arriving in New York in 1796 aboard the privateer America. The career of this two-year-old from Bengal is not known, although it seems she was killed in Rhode Island in 1822.

In 1808, an African elephant was purchased in the nick of time from a New York slaughterhouse by businessman Hachilah Bailey. Old Bet, known today as the mother of America’s carnival business, was put to work in a “circus” consisting of a dog, two pigs, and a horse. In July 1816 near Alfred, Maine, a religious fanatic — outraged that poor farmers were spending hard-earned cash to see an elephant — shot the animal dead.

In 1874, a 3,000-kilogram elephant, Norma Jean, was struck by lightning while parading through the town square of Oquawka, Illinois. Following the tradition of disposing of dead elephants where they fall, the animal was buried on the spot. In Indiana in 1901, Big Charley was shot dead after trampling its trainer to death. It too was buried on the spot; the remains later washed away in a flood.

In 1903, American inventor Thomas Edison arranged to have an elephant publicly electrocuted in Luna Park. Up to that point Edison, in his bitter campaign to discredit the electrical theories of George Westinghouse, had been content to publicly electrocute cats and dogs.

When Topsy, an enraged circus elephant, trampled to death its third trainer in three years, Edison offered to “execute” the animal in a way that would demonstrate once and for all his belief in the dangers of alternating current. The electrocution of this elephant was filmed and apparently the footage can still be viewed at the Coney Island Museum.

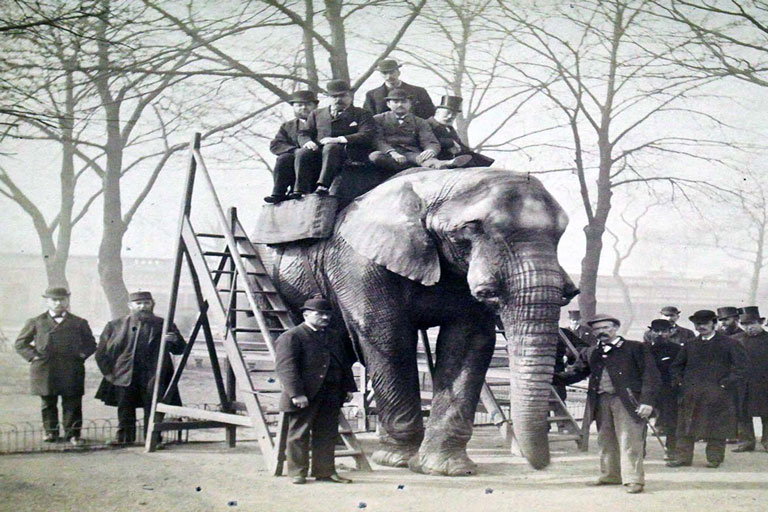

Prior to his arrival in North America, Jumbo, “The Children’s Pet," had lived eighteen years in London, England, where one and a quarter million children, including a youthful Winston Churchill, had ridden on his back.

When British reporters learned that Jumbo was to become the “chattel of a wandering showman,” and an American at that, they were outraged. The London Daily Telegraph was particularly indignant that Jumbo, instead of enjoying “friendly trots with British boys and girls," would now be forced “to amuse a Yankee mob.”

On the fateful night of September 15, 1885, Barnum’s Big Top pitched its tents for a one-night performance in St. Thomas, Ontario. Until then the town was known, if at all, from a brief mention in Anna Jameson’s Winter Rambles and Summer Studies in Canada. In that book she ascribes to the town “three churches, one of which is very neat, and three taverns." It was also, by the time of Jumbo’s arrival, the site of one of Canada’s largest lunatic asylums.

Following the show, as Jumbo was being let out across the tracks, he was struck and killed by a westbound freight train driven at high speed by William Burnip. Quickly, two hundred men armed with rope and tackle managed to topple the immense carcass down the embankment and clear the busy tracks.

The circus — along with the human cannonball, the bearded lady, the tattooed man, the Hindoo snake charmer, the Feegee Mermaid, the New Zealand cannibal, and Joice Heath, the reputed 161-year-old nurse of George Washington — had already packed up and was steaming out of town without even a backward glance at its star attraction.

With a seven-ton elephant lying dead on a railway embankment, residents of St. Thomas were quick to emulate the hucksterism of Jumbo’s famous owner.

Five cents admission was charged to see Jumbo’s carcass. Slivers were chipped off the tusks and sold. For two days Jumbo lay on the ground, at which point Barnum’s personal taxidermists arrived from the U.S. to claim the skin and skeleton. Six local butchers were hired to cut up the meat. The viscera was burnt, and as the smell of broiled elephant wafted through St. Thomas, the Daily Times began selling its hastily printed Jumbo Memorial Tablets,

JUMBO

King of Elephants,

Died at ST. THOMAS, Sept. 15, 1885,

AGED 24 YEARS

The pillar of a people 's hope,

The centre of the world's desire.

All that remained was a flood of elephant grease, bottled and sold as a curative ointment for aches and pains.

Today Jumbo is no longer “the pillar of a people’s hope,” nor perhaps is St. Thomas “the centre of the world’s desire." Nonetheless, the Jumbo industry is still alive. Books have been written (at least two), websites maintained, and a fingernail-sized crystal Jumbo (currently out of stock) is available for $33 (U.S.).

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In 1985, St. Thomas council commissioned a massive elephant sculpture to grace the downtown core. Sculpted in New Brunswick, the concrete Jumbo was transported 1,720 kilometres across the country. In an incident that seems to mirror the sorry history of elephants in North America, the legs were cut off so that it could clear the bridges dotting the Trans-Canada Highway. No tourist brochure mentions St. Thomas without immediately bringing up Jumbo— “the best known non-human that ever lived," as one local booster proudly puts it.

If justice is to be found in the grim history of elephants in the New World, it’s not the justice of the legal system, but rather that of a curse that hovers over the Jumbo story.

The man who captured Jumbo, a German carpenter, Johan Schmidt, died delirious in the Abyssinian highlands. Carl Akeley, sent by Barnum to retrieve Jumbo’s skin, was himself seriously trampled by an elephant and met his death in the Belgian Congo while tracking a bush antelope.

His taxidermist colleague, Professor Henry Ward, was struck dead by a car in Chicago in 1906, becoming one of the world’s first recorded car-accident victims.

Matthew Scott, Jumbo’s personal handler, perished in a poorhouse in Bridgeport Connecticut, in 1914.

William Burnip, the engineer who drove the train on that fateful day, and later fashioned a tin elephant that he placed over the headlight of his deadly locomotive, was killed in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906.

Finally, after four years of touring, Jumbo’s hide, which weighed 725 kilograms, was placed in Barnum’s Museum at Tufts College, Massachusetts. In 1975 the museum and all it contents were destroyed by fire.

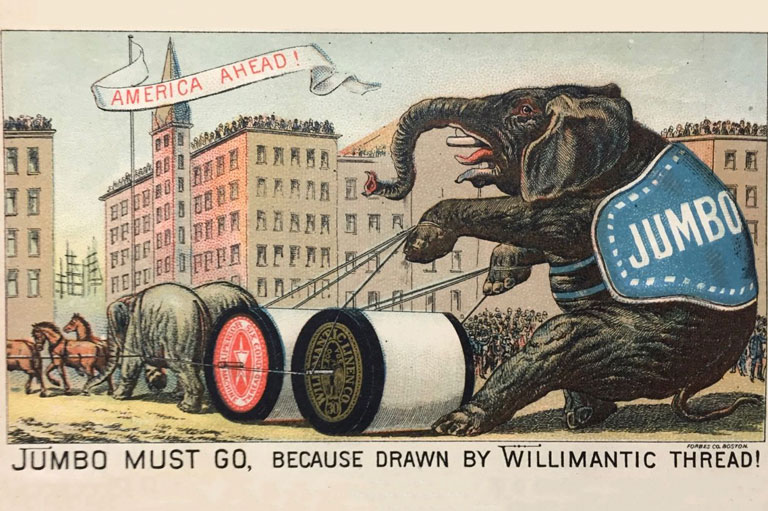

P.T. Barnum’s purchase for $10,000 of Jumbo from the London Zoo in 1882 created a furor of indignation in England. Queen Victoria, the Prince of Wales, and other notables protested the potential loss of what had come to be thought of as a national treasure. The Daily Telegraph cabled Barnum with an offer to buy back Jumbo at any price; attempts were made to seek an injunction against Jumbo leaving the country; and thousands of remonstrating letters were written to newspapers. There was no joy. Jumbo sailed to the New World on the Assyrian Monarch and spent the few years until his accidental death being exhibited all over the Untied States and Canada as the focal point of the Barnum and Bailey Circus. He was viewed by an estimated 20 million people.

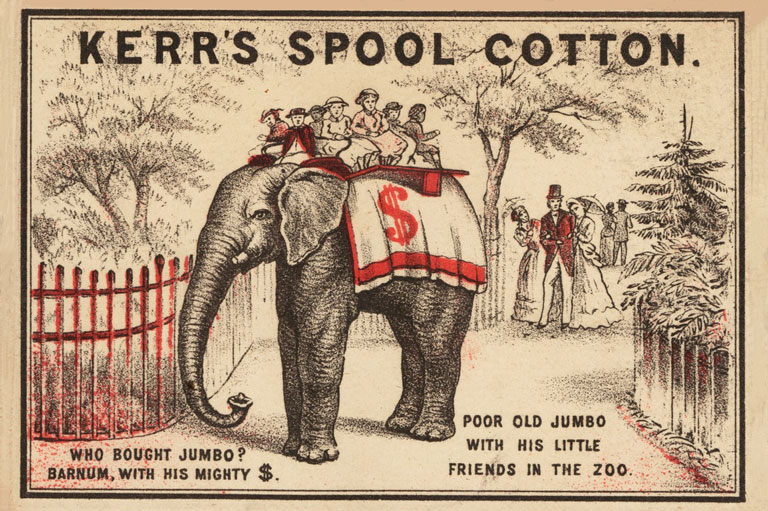

The image to the left is a postcard which, on the the back reads in part:

Jumbo has lived a happy life, and has had the privilege of affording pleasure to the Royal children, besides hundreds of thousands of others who have enjoyed a ride on his back. He possess wonderful sagacity, which affords an index to what, where he a human being, would be called moral character. It is customary with him, after each promenade, to back himself into a position conveniently close to a flight steps; and while a change in his freight of humanity is in process, he enjoys bread, buns, biscuits, and oranges from the hands of those around him.

According to the card, in leaving England Jumbo was also taken away from his “partner, known by the name of Alice, to whom he was much attached.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!