Willing to be Thrilling

On Saturday evening, September 30, 1916, HRH Princess Patricia was among the audience at Ottawa’s Russell Theatre for what had been advertised as the “Season's Social Event.” Maud Allan, “The Great Symphonic Dancer,” was to perform classic and oriental dances accompanied by her own orchestra , conducted by the Swiss musician Ernest Bloch.

According to a newspaper report, Maud was invited the next day to Rideau Hall, the governor general’s residence, to dine with the Duke and Duchess of Connaught and their daughter, Princess Patricia. Connaught, third son of Queen Victoria, likely had paid several visits to London’s Palace Theatre to see Maud Allan dance before the First World War, no doubt in the company of his brother, King Edward VII.

The Canadian-born dancer’s next stop was Toronto, where she appeared at the Royal Alexandra Theatre from October 5 to 7. “With pride, Toronto claims this exceptional genius and her remarkable and soul-satisfying art,” ran the headline in The Musical Courier. The Mail and Empire declared: “Famous Dancer Pays First Professional Visit to Native City.” The Globe’s drama critic E.R. Parkhurst told his readers that the Toronto-born dancer had won “signal triumphs in the principle cities of Europe.”

It had been nearly four decades since Maud, together with her older brother, Theodore, and her parents, shoemaker William Allan Durrant and mother, Isabella, left Toronto during the depression in the 1870s to settle in San Francisco. Isabella had high hopes for her son and daughter. Both Durrant children graduated from the three-year arts program at Cogswell College. Theo was destined to become a medical doctor, and Maud to be a famous concert pianist.

Maud’s Cogswell College graduation photograph shows a pert, young woman with a clear complexion, her long, wavy blond hair swept up off her face and gathered into a bun on the crown of her head with artfully arranged curls on her forehead. Away from the California sun and Isabella’s regime of lemon rinse treatments, Maud’s hair would turn a light brown.

From an early age, Maud had shown unusual musical talent. Her mother arranged for her to study with Professor Eugene Bonelli at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

He may have left his mark on Maud in a more unconventional way. It is alleged that he pioneered and performed a surgical procedure on more than 575 of his students that severed the accessory slip of the tendon of the ring finger to give their hands more flexibility and a wider stretch of fingers.

Bonelli is quoted as saying, “The brain conceives, the fingers execute. Hence the necessity of training them in their duty. Liberate them first, if you would lessen your labour.” He encouraged the Durrant family to send Maud to Germany to take advanced studies as he had.

On Valentine’s Day, 1895, the twenty-two-year-old Maud left her family to travel to Berlin. She spoke not a word of German, had no guarantee of being accepted into the highly competitive music program, and had a woefully inadequate amount of money. Her one asset was her abounding self-confidence.

“I remember when it was settled and my brave, courageous mother was blinking back her tears, I said with the egotism of a very young girl: ’Some day, dear, you shall come over there, when I have made you proud of your daughter.’”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Maud carried with her a small, tan, leather diary inscribed: “From brother on my departure for Europe — San Francisco — Berlin, Germany, February 14, 1895.” Because she wrote regularly in a series of such diaries, we know a great deal about Maud during the next few years.

With admirable aplomb, Maud immediately began to learn German. She got herself accepted at the Konigliche Akademishe Hochschule fur Musik (Berlin Royal Academy High School of Music) and earned extra money by giving English lessons. She found an affordable, spacious, blue-painted room in a pension and rented a grand piano on which she arranged family photos to make it a cozy home. All was well.

Soon after arriving in Berlin, Maud found herself bothered by strange premonitions. “Today I feel so unsettled. I do not know why. But I could not neither study, practice, or read,” she wrote on March 28. A few days later she noted that she had not received a letter from home. “What can be the matter?”

The “matter” was beyond anything she could ever have imagined. On April 15 her brother had been arrested in San Francisco and charged with the murder of two young women. The pair, Blanche Lamont and Minnie Williams, were both members of Emmanuel Baptist Church where the Durrant family also worshipped.

Theo’s trial began on September 3, 1895. The facts, as they came out, were far more damning than the bare bones story Maud had been told by her mother. In October the jury convicted Theo of murder in the first degree. After appeals all the way up to the Supreme Court failed, Theo Durrant was hanged at San Quentin on January 8, 1898.

Despite her mother’s suggestion that Maud return home to help pay for Theo’s legal appeals, she remained in Germany and struggled along with her music. A school friend of Maud’s brought her the news in Berlin on January 10. “Oh God, I bear up but my poor parents — how do they! Darling brother — would to God I could have seen you once more before you were taken from us.”

To restore respect and dignity to her family, Maud felt it was imperative for her to succeed as an internationally acclaimed concert pianist. In the summer of 1901, she successfully petitioned to enter the famed Italian pianist Ferruccio Busoni’s master classes in Weimar. A photo of that 1901 master class shows an attractive Maud standing directly behind the seated Busoni and his protege, Egon Petri.

In memoirs written in 1954, a fellow student of that time remarked that Maud Allan never touched the piano during that summer. It may have been that in close proximity to some of the most talented young musicians from Europe and North America, Maud realized that a career as a leading concert pianist was far beyond her talent.

In no way, though, did she give up the determination to fulfill her mother’s dreams for her that she should become a star. Sometime that year Maud figured out how she might capitalize on her most obvious assets: her beauty and her musicality. She would become an expressionist, barefoot dancer — an art form that barely existed at the turn of the twentieth century. The word “barefoot” brings to mind dancers such as Isadora Duncan and perhaps Mata Hari.

Contemporary accounts suggest that it was Busoni and his wife, Gerda, who encouraged Maud to become a dancer. Perhaps Busoni, dedicated to challenging artistic conventionality, recognized the possibility of Maud expressing her love and talent for music through her body. And he would have been well aware it was a most graceful and voluptuous body — Busoni began a love affair with Maud that summer .

Back in Berlin she became a part of his coterie, meeting and mingling with an exciting and avantgarde group. In 1903, Maud and another new male friend, Belgian music critic and minor composer Marcel Remy, attended a performance of Max Reinhardt’s seminal theatre production of Oscar Wilde’s play Salome. Then and there they decided to create their own dance version of Salome.

Quite a while passed before Maud began performing on stage as an expressionist dancer. Remy came to her rooms daily to play the piano while she practised interpreting the music. He arranged for her first concert in Vienna at the end of 1903 and a second early in 1905 in Belgium.

Her mother, somewhat dubious about the respectability of barefoot dancing, was always fearful that people would make the connection between Maud and her infamous brother. Responding to Maud’s letter describing her performance in Berlin in 1905, Isabella inquired anxiously: “Were there any Americans present, or did anyone know or make it known who you were?”

On December 28, 1906, the curtain went up on Maud’s Vision of Salome dance at the Carl Theatre in Vienna. Adding spice to the occasion, the management of its original venue, the Court Opera House, cancelled out after seeing Maud’s costume in the dress rehearsal.

Marcel Remy was not there to support her. Just a few days before the Viennese debut of their joint venture, he had died in Berlin at the age of forty-one .

Her appearance on stage clad in a breastplate of glittery jewels and strings of pearls clearly showing the outline of her breasts must have caused a ripple through the audience at the Carl Theatre. Maud’s skirt was dark, but transparent, with strings of beads looped over her exposed midriff. Her feet and arms were bare.

She wore a headdress of pearls and her eyes were ringed with kohl. Her wrists and hands were ornamented with jewels. Almost as shocking was the life-like head of John the Baptist, a prop which Maud picked up and danced around with before finally sinking to the floor in a deep swoon.

Maud’s choreography consisted of two works: Dance of Salome and Vision of Salome. In the first dance, she enacted the Biblical story of Salome and John the Baptist; in the second she interpreted Salome’s emotions after she had persuaded Herod to behead the prophet.

After ten years of struggle, Maud finally received a series of breaks. In May 1907 she secured an engagement at the Paris Palace of Varieties.

This, in turn, led to an invitation by Yvette Guilbert, France’s cult-figure cabaret singer, for Maud to take part in a charity matinee at the Theatre Sarah Bernhardt. Next came a request to perform privately at Marienbad, the Bohemian spa town, before none other than King Edward VII.

Another spectator who had caught her act in Paris was Alfred Butt, the bright, young managing director of London’s up-market Palace Theatre of Varieties. In an article in a 1909 Strand magazine, he recalled that although he had spotted her potential, the five friends with him were not impressed.

“I said that we had decided to engage her for the Palace, and they told me with absolute unanimity that in London she would be a failure. What did happen? Well, all London knows now. And she made many thousand of pounds for us in five months and will be making more soon.”

All London did know! By introducing Maud Allan at a special preview matinee on March 6, 1908, before an audience of grandees that included the Duke of Westminster and Lady Sassoon, Butt adroitly established Maud’s dancing as an art of the highest and most respectable calibre.

It hardly hurt that the King of England had already seen her and had most definitely approved. The news spread quickly that Maud’s act at the Palace was the must-see of the society season. The Lady: A Journal for Gentlewoman reported on April 2, 1908:

A new sensation is certainly to be found just now at the Palace Theatre, where Miss Maud Allan has danced herself into favour. There was a very full house at a special matinee given for her this week, and Society was well represented. The Prince and Princess of Wales went to see this charming young Canadian dancer before they left for Germany and the Queen expressed the intention of witnessing her artistic performance with the Empress Marie.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Some people found it hard to decide whether she was merely a sensationalist or presenting a new dance art form. Many, despite themselves, were charmed by her.

Novelist Katherine Mansfield described Maud “as everything that is passing and coloured and to be enjoyed.” She intuitively recognized Maud’s dancing as a means of expressing the music and wanted to do the same with words. Maud’s popularity reached out beyond society, intellectuals, and emancipated women.

The relatively new technologies for reproducing photographic images made it cheap to produce picture postcards. Maud Allan cards, especially those of her in the provocative Salome costume, were easily the most sought-after.

Other cards of Maud in street clothes portrayed her as the quintessential Edwardian beauty complete with magnificent hats bedecked with flowers and feathers .

For eight months, Maud danced daily at the Palace Theatre of Varieties to sell-out audiences. She remained a constant attraction, while her “ellow turns” changed. Thus, on May 2, 1908, she was given twenty-five minutes in between “the Juggling McBains” and “Prince Arthur and his sailor boy, Jim.” In August she shared the billing with “Professor Macart's troupe of comedian and athletic monkeys.”

An injury in late October 1908 caused her to retire temporarily. Butt predicted correctly that upon her return, she would make even more money for both the Palace and herself.

In 1909 and 1911, she came back to continued acclaim. She also toured the provinces, occasionally receiving criticism for her scanty costumes by the local authorities. She introduced new works into her repertory, but what audiences insisted on was the Vision of Salome.

Just before the First World War, travel had never been easier. Ocean liners and transcontinental railway lines with Pullman sleeping cars made long voyages fast and comfortable.

Artists and entertainers emerged as international celebrities roving vast distances by either or both of two routes: across Europe to Russia or across the Atlantic to play in towns and cities from coast to coast in the United States and Canada, and then, perhaps, on to South America or Australia and New Zealand.

It is said that Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova toured more than 400,000 miles before dying in a Belgium hotel room.

In 1910, Maud Allan joined the international circuit. Between then and 1917, she travelled to Russia, made two nationwide tours of North America, and spent over two years in the Far East. Everywhere she went, audiences wanted to see her Vision of Salome. While visiting with her parents in California in 1915, she starred in a silent movie called The Rug Maker’s Daughter. Unfortunately, no film survived to give a sense of what her dancing really looked like.

Readers of London’s Sunday Times and the Morning Post on February 10, 1918, would have raised their eyebrows at a notice advertising a private performance of Oscar Wilde’s play Salome featuring Maud Allan in the lead role. The reason for the private performance was straightforward. Wilde’s play, written in 1891–92, was still banned from public performance in England.

By this time England had been at war for four years. An ultra right-wing Conservative MP, Noel Pemberton Billing, was convinced that the British government was in secret peace negotiations with the Germans.

Billing, who also published a subscription newsletter called the Vigilante, was promulgating “the Black Book” theory, which implied that Germany’s consistent military superiority was the result of British military strategies being disclosed by blackmailed members of its ruling class.

The Black Book supposedly contained the names of 47,000 men and women whose sexual orientation made them susceptible to blackmail. In his eccentric way, Billing did have a point, if a very small one. Quite a few members of Britain’s upper classes were indeed homosexual or bisexual.

The February 16, 1918, issue of the Vigilante included a brief paragraph with a startling headline: “Cult of the Clitoris.” It went on to declare: “To be a member of Maud Allan’s private performance in Oscar Wilde’s Salome, one has to apply to a Miss Valetta of 9 Duke Street. Adelphi, W.C. If Scotland Yard were to seize the list of those members, I have no doubt they would secure the names of several thousand of the first 47,000 [in the Black Book].”

Maud Allan and the producer, Jack Grein, who was also the drama critic for The Times, each charged Billing with libel. This was exactly what Noel Pemberton Billing wanted — the opportunity to publicize his theories. All the London newspapers carried daily reports of the trial proceedings.

Maud was called to the stand on the first day of trial at London’s Old Bailey. The Daily Express described her as a “fascinating figure — a tall, slender, delicately featured woman [who] speaks with a slight accent, a suggestion of an Irish brogue.”

She handled herself well until Billing asked her to state her full name. “Beulah Maud Allan Durrant,” she replied no doubt with a sinking feeling realizing where Billing was going.

Next he handed her a green-cover book titled Celebrated Criminal Cases of America and asked if the William Henry Theodore Durrant, who had been executed in San Quentin, was her brother. She was forced to answer yes. The inference was that Maud shared that bad blood.

Thereafter, the trial judge lost complete control of the proceedings, allowing it to turn into a platform for Billing to promote his eccentric political views. The judge also allowed the witness Lord Alfred Douglas to viciously repudiate his one-time lover, Oscar Wilde. As the bizarre trial progressed Maud became less and less relevant. In a travesty of justice, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty for Billing.

As one would expect of a woman who overcame the shame of having a brother executed for murder, to go on to dance before royalty, this second public humiliation did not destroy Maud Allan.

She continued to dance and branched out as an actress, appearing as the elderly abbess in the 1932 London production of Max Reinhardt’s The Miracle, a member of a distinguished cast that included dancers Tilly Losch, Leonide Massine, and Lady Diana Cooper (who as Diana Manners had been sent weekly by her mother in 1908 to watch Maud Allan perform at the Palace Theatre).

Her last public dance appearance was at California’s outdoor Redlands Bowl in 1936.

A spinster with no children, Maud’s last years were increasingly lonely. While her father had died in 1917, a much greater loss was the death of her mother in 1930.

Isabella had taken on the role of Maud’s travelling companion and later lived with her daughter in London at her Regent’s Park residence, West Wing. After bomb damage made West Wing uninhabitable, Maud reluctantly returned alone to California, where she lived for fifteen more years relying more and more on the kindness of long-suffering friends.

At one time earning the sum of £500 per week, Maud Allan died a pauper at the age of eighty-three. True to her artistic vision, she had prearranged her funeral, requesting an organ solo to be played in the garden of the North Hollywood cemetery. She died in Los Angeles in 1956.

Allanibilia: Artifacts from the Maud Allan Collection

In the 1990s, Dr. Felix Cherniavsky, Maud’s biographer and the son of one of the musical Cherniavsky Trio who accompanied Maud on several international tours, donated his personal collection of Maud Allan ephemerae, including letters and her Berlin diaries, to a private dance archives, Dance Collection Danse in Toronto.

Allan’s Salome costume, which shocked, bemused, and fascinated audiences around the world, is now tucked away in an archival box in a small house on George Street — the very same street where Maud Allan Durrant lived as a little girl.

Popular in the early 20th centiry, this cigarette “silk” was issued at the height of the “Salomania” rage, but neglected to use an authentic Maud Allan image or signature.

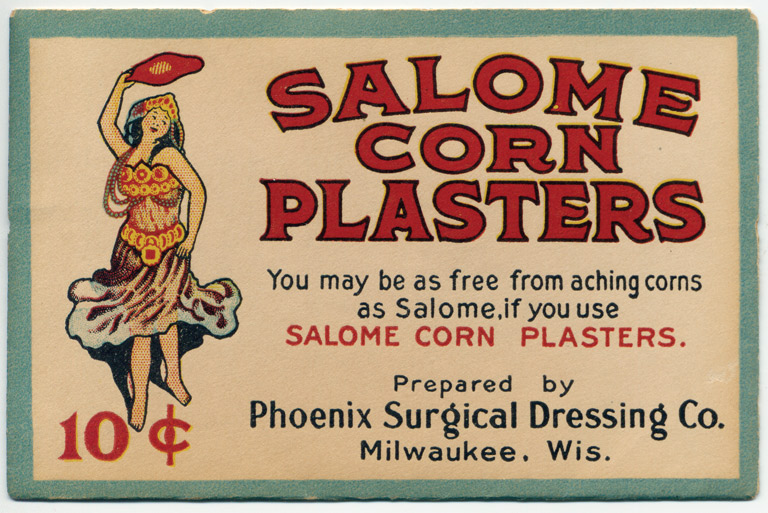

Salome corn plasters from 1906 promised that you, too, could be “as free from aching corns as Salome.”

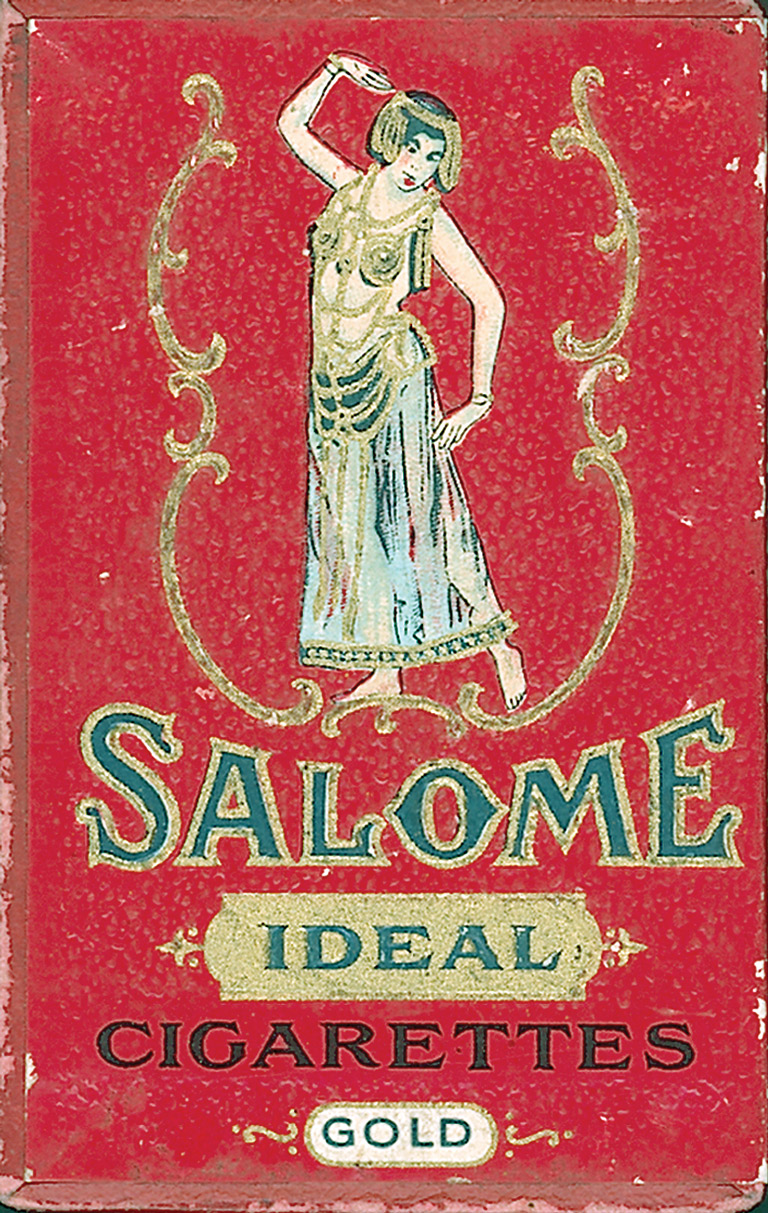

Salome cigraettes were among the many forms of merchandise that accompanied the “Salomania” craze.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!