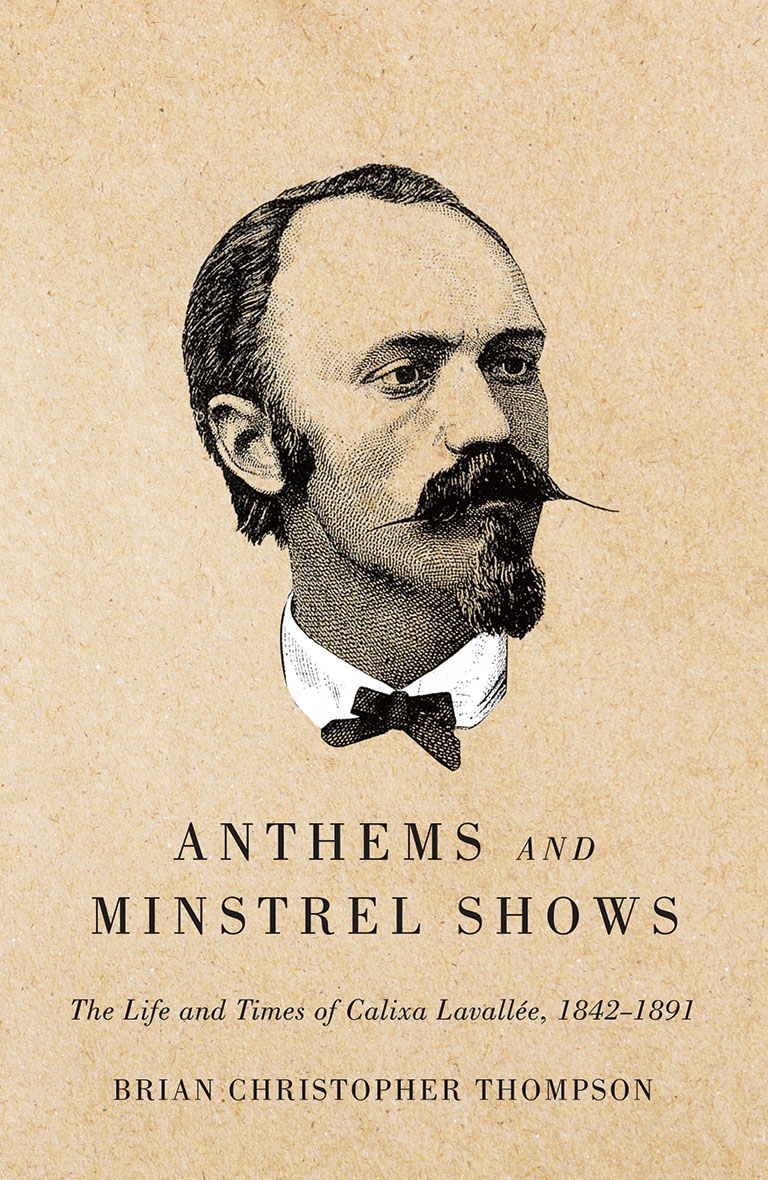

Anthems and Minstrel Shows

Anthems and Minstrel Shows: The Life and Times of Calixa Lavallée, 1842–1891

by Brian Christopher Thompson

McGill-Queen’s University Press

522 pages, $49.95

Calixa Lavallée was one of early Canada’s finest musical figures. Despite this, he remains an obscure figure within our national history. Having enjoyed a career that took him across North America and into Europe, he is best remembered, when remembered at all, as the composer of “O Canada.” Anthems and Minstrel Shows, by Brian Christopher Thompson, aims to clarify who Lavallée was as well as the nature of his life’s work.

The book’s first part examines the years from 1842, the year of Lavallée’s birth in the Richelieu Valley, to 1873, when he relocated to Paris. Having shown an early predilection for music, Lavallée moved to Montreal as a teenager to receive instruction.

In 1859 he headed to the United States to launch his career, joining a Rhode Island-based minstrel show. Quickly rising to the position of musical director, the multi-instrumentalist, along with his troupe, followed a serpentine route down the eastern seaboard to Louisiana and back again. When the American Civil War erupted in 1861, Lavallée served a stint as a musician within the Union Army before making a brief return to the minstrel show circuit. By 1863 he was back in Montreal, where he continued performing while also contributing to the anti-Confederation L’Union nationale broadsheet. After three years in his home province, Lavallée made a final return to minstrel shows.

Lavallée eventually soured on the minstrel show format, believing it de-emphasized serious musicianship in favour of comedy. Feeling that his work would be better appreciated if he received formal training in Paris, he headed to Europe in 1873 in order to study piano and composition.

This marked a turning point in his career, as he returned to Canada two years later with a focus on classical music and an interest in “developing musical life in Canada, both through concerts and large-scale productions, and through education.” During this period Lavallée’s career reached new heights. He received a commission to write a cantata for the inaugural visit to Quebec City by the new Governor General in 1878 as well as a commission to create a national song — which turned out to be “O Canada” — from organizers of the Congrès Catholiques Canadiens-Français in 1880.

Despite his newfound recognition, Lavallée grew increasingly bitter about the life afforded to musicians in his homeland. He wrote, “an artist is not meant to rot in an obscure place and especially in an even more obscure country.” Such feelings were exasperated by his failure to secure support for the creation of a conservatory in Quebec — something he believed was necessary to elevate the place of “serious” music in the province — and they inspired his return to the United States.

Living in Boston, he achieved renown for his work with the U.S. Music Teachers’ National Association; Lavallée promoted the work and careers of American composers and served on behalf of the region’s large French-Canadian diaspora. After spending the final year of his life as musical director at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, he succumbed to a lengthy illness in 1891.

Lavallée is an intriguing figure, and Thompson does an excellent job exploring the nuances of his life. Anthems and Minstrel Shows addresses the important role of music within society and the way politics was articulated in the early days of our country.

Particularly interesting for this reviewer is the book’s epilogue, which examines the changing recognition of Lavallée in Canada and the United States throughout the twentieth century as well as the politics of “O Canada.” This book is recommended for those who are interested in the history of music in Canada as well as for anyone wanting to learn more about the intersection of culture and nationalism.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement