Ties of Kinship

Until recently, both Confederation and the Indian Act that flowed from it eclipsed most of the Treaty relationships in the minds of the non-Indigenous population of Canada. Today, the country finds itself returning to the Treaties and rekindling the relationships that sustained the many peoples on these lands for centuries prior to 1867.

Part of this national introspection is the rediscovery by non-Indigenous peoples of the ancient and enduring relationships between First Nations and the Crown that were enshrined in such Treaties as the 1764 Treaty of Niagara.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763, which was instrumental in laying the foundation for the Treaty of Niagara, has often been described as the “Indian Magna Carta” — a seminal document that guarantees rights to Indigenous peoples in their relationships with the British and, later, the Canadian governments.

The proclamation by the British King George III, who reigned from 1760 to 1820, recognized First Nations’ “possession” of vast areas of land and decreed that Indigenous people “should not be molested or disturbed in the Possession of such Parts of Our Dominions and Territories as, not having been ceded to or purchased by Us, are reserved to them, or any of them, as their Hunting Grounds.”

The proclamation also set out a structure for negotiating treaties between the British Crown and First Nations, stating that “whereas great Frauds and Abuses have been committed in purchasing the Lands of the Indians ... We do, with the Advice of our Privy Council, strictly enjoin and require that no private Person do presume to make any purchase from the said Indians of any Lands ... but that, if at any Time any of the said Indians should be inclined to dispose of the said Lands, the same shall be Purchased only for Us, in our Name, at some public Meeting or Assembly of the said Indians, to be held for that Purpose by the Governor or Commander in Chief of our Colony.”

Yet, as Elders and Knowledge Keepers across the continent have reminded us, King George III’s proclamation is only half of the story — specifically, the non-Indigenous half. After all, the Royal Proclamation is merely a written document capturing a static moment in time. “Treaty” can also be defined as an action word, a living agreement that evolves as time passes.

Similarly, the meanings of the wampum belts that embody Treaties can never be captured in one interpretation. “Contextualization of the Proclamation reveals that one cannot interpret its meaning using the written words of the document alone,” wrote John Borrows, the Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law at the University of Victoria, in his 1997 article “Wampum at Niagara: The Royal Proclamation, Canadian Legal History, and Self-Government.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

“To interpret the principles of the Proclamation using this procedure would conceal First Nations perspectives and inappropriately privilege one culture’s practice over another,” Borrows wrote, explaining that, because Indigenous cultures were orally based, “First Nations chose to chronicle their perception of the Proclamation through other methods such as contemporaneous speeches, physical symbols, and subsequent conduct.”

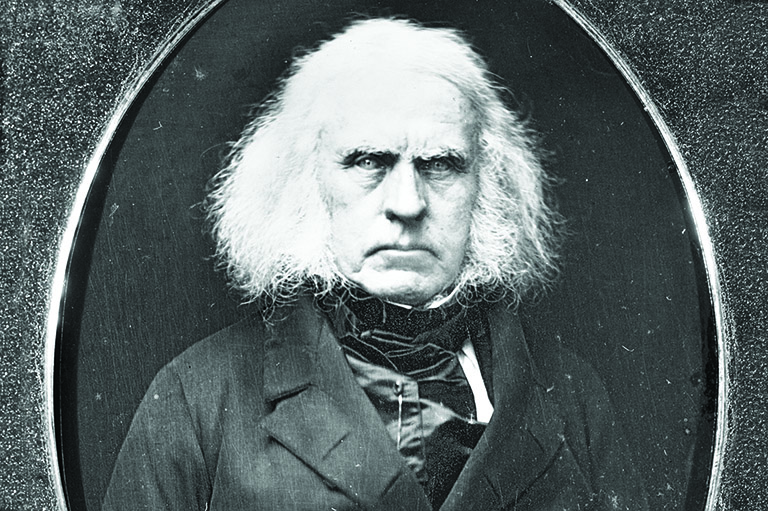

When copies of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 were circulated among the First Nations surrounding the Great Lakes, William Johnson, the King’s superintendent of Indian affairs, knew that the document was meaningless unless it was ratified by First Nations communities. Simply imposing British interests in the Great Lakes watershed by using military force clearly wasn’t going to work.

General Jeffery Amherst, the commander-in-chief of British forces in North America from 1758 to 1763, had tried this approach. When faced by an Indigenous uprising against British rule led by Odawa Chief Pontiac (Obwandiyag) in 1763, Amherst had even advocated genocidal tactics, such as deploying blankets that would carry the smallpox virus.

But the victories of the Odawa and allied First Nations in the field proved that British forces were no match for the people of the region fighting on their own territory. Noting Pontiac’s capture of nine British forts in the region of the Great Lakes and the Ohio Valley, imperial officials abandoned Amherst’s campaigns and heeded Johnson’s counsel for diplomacy, using Indigenous protocols brought forward by his partner, Molly Brant, a Mohawk Clan Mother of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

The result was the Great Council at Niagara in 1764 between the British Crown, represented by Johnson, and approximately two thousand delegates from at least twenty-four First Nations from across the Great Lakes region.

After a month of negotiations — including the exchange of eighty-four wampum belts woven by hand using sinew with quahog and whelk shells — the Treaty of Niagara was forged. This established a familial relationship between First Nations peoples and the British King, and it extended into the heart of the continent the Silver Covenant Chain of Friendship — an ongoing system of alliances between the British and First Nations that originated with agreements between the Kanyen’kehà:ka (Mohawk) and the colony of New York in the early seventeenth century.

Many people see the Treaty of Niagara, including the wampum belts exchanged at its inception, as the founding of what we now call Canada. As Borrows noted in his article, the wampum belts — woven at the behest of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous delegates — formed an integral part of the Treaty: “Some principles which were implicit in the written version of the Proclamation were made explicit to First Nations in these [wampum belts] and other communications.”

For example, one of the wampum belts presented during the Treaty of Niagara negotiations was a two-row wampum, consisting of two rows of purple on a white background. This style of wampum belt, dating back to the earliest contact between Europeans and Haudenosaunee, expresses a relationship of equality between the two Treaty partners. The two rows of purple symbolize two vessels travelling down the same river together: one vessel, a canoe, carries the First Nations people, their laws and customs, while the other vessel, a ship, carries the European people, their laws and customs. Although they travel side-by-side, each one remains distinct from the other.

“The two-row wampum belt illustrates a First Nation/ Crown relationship that is founded on peace, friendship, and respect, where each nation will not interfere with the internal affairs of the other,” Borrows explained.

At the heart of the Treaty of Niagara, and of most Treaties, is a relationship with the sovereign grounded in ties of kinship. The dynamic created when the Crown and First Nations peoples became family entrenched the need for trust, honest communication, and honour. If familial love is woven into a Treaty relationship, it allows for disagreement without disrespect. A familial relationship requires flexibility in order to exist. As new dynamics or unforeseen conflicts emerge, they have to be incorporated into the relationship through negotiations among the Treaty partners.

The Crown provided the framework needed for non- Indigenous peoples to establish Treaty relationships with First Nations. It was through the Crown, especially the institution’s ability to transcend the settlers themselves, that the ideals of non-Indigenous society could be effectively translated.

As an institution, the Crown is purposely vague in its definition, which enables it to reflect the highest aspirations — indeed the honour — of the society it represents. One of the primary roles of the King, as King of Canada, is to be the living embodiment of the Canadian state, with all its nuances. The Crown provides the legal and political concepts upon which the Canadian state rests, yet it simultaneously exists in a metaphysical realm. Like the Treaties, the Crown, as a metaphysical concept, must be constantly renewed by those it is intended to serve.

Remarkably, there was no space in Canada dedicated to commemorating and educating people about the Treaty of Niagara until Queen Elizabeth II created the Chapel Royal at Massey College in the University of Toronto on June 21, 2017. In the Anishinaabemowin language, the chapel’s name is Gi-Chi- Twaa Gimaa Kwe, Mississauga Anishinaabek AName Gamik, meaning “the Queen’s Anishinaabek sacred place.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Originally, a chapel royal was not a physical building, but rather a retinue of chaplains and choirboys who followed English sovereigns in their travels around the country. Later, British monarchs designated certain churches as chapels royal, and they imported the institution to North America, where it became fused with their personal relationships to First Nations peoples.

Queen Anne, who reigned from 1702 to 1714, ordered the establishment of a Mohawk chapel at Fort Hunter in what is now New York State in 1711. This occurred after four Mohawk chiefs — including Molly Brant’s grandfather, Chief Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, or Peter Brant — visited the Queen in England to request military aid and Anglican missionaries. The chapel at Fort Hunter was destroyed during the American Revolution, but new chapels were built in the mid-1780s by First Nations people who moved to areas north of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario as a result of the revolution.

His Majesty’s Royal Chapel of the Mohawks near present-day Brantford, Ontario, and Christ Church, His Majesty’s Chapel Royal of the Mohawk near Deseronto, Ontario, were recognized as chapels royal by King Edward VII in 1904 in recognition of the Mohawks’ long-standing support of the British Crown.

The creation of the Chapel Royal at Massey College recalls the ancient and enduring bonds established through Treaties that predate Canada itself, while at the same time providing a space to learn about and to discuss one of the most important relationships established on these lands.

When the importance of the family relationship between the King and First Nations peoples is understood, it becomes clear why such a space was created in the year of Canada’s sesquicentennial. This was a familial act of reconciliation that recalled ancient obligations and connected those obligations with the future of Canada.

One of the centrepieces of the Chapel Royal at Massey College is a mural created by Philip Cote, a First Nations artist and this article’s co-author. On permanent display near the entrance to the subterranean chapel, the mural literally grounds visitors with an Indigenous voice from the moment they walk in the door.

The mural illustrates the negotiation of the Treaty of Niagara and the nature of First Nations Treaties as living agreements that evolve and change. The Silver Covenant Chain of Friendship Wampum, one of the belts presented by Johnson at the Treaty’s conclusion, features prominently in order to represent the union of First Nations people and the Crown. A replica of this wampum is on display near the chapel’s altar, and it is also depicted on a mosaic created by glass artist Sarah Hall. Key figures such as Molly Brant, Johnson, and Pontiac are depicted, as are delegates from the Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee, Shawnee, Suk Fox, Anishinaabeg, and Mississauga nations. Visitors to the chapel are thus invited to understand the full story of the Council of Niagara and what was discussed.

Invoking Treaty, the Chapel Royal at Massey College is a living space, committed to the recognition of relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people that did not begin or end with the Royal Proclamation, but stretch back generations. The proclamation was not ratified by First Nations peoples until it reflected that reality. Now as then, these relationships are contemporary, a fact that is demonstrated by the revival of many of the protocols practised at the chapel between representatives of the Queen and members of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation.

While the British North America Act of 1867 empowered Canadian governments to act as if the Treaties did not exist, the relationships between the sovereign and First Nations were not extinguished — a fact highlighted by countless delegations to Buckingham Palace and petitions handed to vice-regal representatives, right up until the present day.

On a visit to Canada in May 2022, King Charles III — then Prince Charles — met with First Nations chiefs during a stop in the Northwest Territories and participated in a drum dance with members of the Dene First Nation in Dettah, a small community near Yellowknife.

“All leaders have shared with me the importance of advancing reconciliation in Canada. We must listen to the truth of the lived experiences of Indigenous peoples, and we should work to understand better their pain and suffering,” he said in a speech in Yellowknife on May 19. “We all have a responsibility to listen, understand, and act in ways that foster relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada.”

Several First Nations chiefs attended the coronation of King Charles III in London, England, in May 2023, and three of them — Assembly of First Nations National Chief Rose-Anne Archibald, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami President Natan Obed, and Métis National Council President Cassidy Caron — had a private audience with him at Buckingham Palace. The audience was arranged by Governor General Mary Simon who, as an Inuk, is the first Indigenous person to hold the office of Canadian Governor General. “We really have to come full circle with the Crown, to come back to that place of deep respect and gratitude,” Archibald told the CBC.

The Crown has long acted as a conduit for non-Indigenous peoples to connect with their First Nations partners. Generations of neglect have tarnished their relationship, straining it almost to the breaking point; but the opportunity is there for renewal. Our national symbols are expected to reflect the highest ideals — and the honour — of Canadian society.

Register to receive your FREE educational package devoted to Treaties and the Treaty Relationship.

Packages are aimed at Grades 2–7 and Grades 7–12, and available in both English and French.

Canada's History magazine was established in 1920 as The Beaver, a Journal of Progress. In its early years, the magazine focused on Canada's fur trade and life in Northern Canada. While Indigenous people were pictured in the magazine, they were rarely identified, and their stories were told by settlers. Today, Canada's History is raising the voices of First Nations, Métis and Inuit by sharing the stories of their past in their own words.

If you believe that stories of Canada’s Indigenous history should be more widely known, help us do more. Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share Indigenous stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

More from the Treaties issue

These articles, as well as the corresponding educational resource package, can be found on the French side of our site.

Encouraging a deeper knowledge of history and Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

The Government of Canada creates opportunities to explore and share Canadian history.

The Winnipeg Foundation — supporting our shared truth and reconciliation journey.