Living Well Together

“A long time ago when the Treaties were made, one of the Chiefs got up and pointed towards the heavens and he said, ‘The sun is my father, and the land is my mother. They teach us we have a responsibility in our generation, in our lifetime. … Up to the horizons, beyond that is the seven generations, as far as you can see, that’s our responsibility — to teach those generations about our wisdom and our knowledge about our people.’ We have a responsibility to keep the Treaty alive in our lifetime for future generations.”

– Anishinaabe Elder Harry Bone

Anishinaabe law tells us that land is not to be owned. Rather, we are in a relationship of respect with the land, with a sense of belonging to the land or “being of the land.” Non-Indigenous legal systems, however, are primarily based in ideas of land ownership and possession.

Treaties were made by Indigenous nations and representatives of the Crown in order to settle land questions. For example, the Anishinaabe of Treaty 1 petitioned the Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba to enter into a Treaty negotiation in order to ensure protection against the encroachment of white settlers who were taking timber from Anishinaabe lands.

The history of Treaty making and Treaty interpretation in Canada has been varied and sometimes controversial. Canadian law has been used as a tool to oppress Indigenous people and to dispossess them of their sacred relationships with land.

Although protection for Treaties was made explicit in the Canadian constitution in 1982, the prior disregard for Treaty promises and the ongoing breaches of Treaties by Canadian and provincial governments have continued to create disharmony between Indigenous people and the Crown.

For decades, Treaties have been interpreted by Canadian courts and the Canadian government to the detriment of Indigenous people. Courts have generally ignored the Indigenous legal principles that were instrumental in the making of Treaties.

Provincial and federal governments continue to view historic Treaties as primarily relating to the acquisition of lands and resources. Indigenous understandings rooted in Indigenous laws have been systematically cast aside in favour of Western legal concepts that privilege notions of private land ownership and resource exploitation.

As I argue in my book, Breathing Life into the Stone Fort Treaty: An Anishinabe Understanding of Treaty One, Treaty interpretation and implementation should take into account Indigenous laws and legal systems.

According to Indigenous laws, Treaties are jointly negotiated agreements between nations that confirm promises to live in relationships of sharing. They are grounded in respect, renewal, and reciprocity.

Not all historic Treaties were created equally or similarly. In eastern Canada, Peace and Friendship Treaties helped to establish peaceful relations with newcomers before Canada was a concept (or a political reality).

From the early days of the fur trade era, voyageurs, company men, traders, and companies created allegiances and kinship with Indigenous people, establishing what historian Jim Miller has characterizedas commercial compacts or fur trade Treaties. The French, Dutch, and English negotiated Treaties that built on those existing relationships.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Shortly after this very early period of Treaty making, a 1763 Royal Proclamation required that any lands acquired from the Indigenous people could only be made open to purchase and settlement by the Crown after a public assembly and via a majority vote by the Indigenous population of the territory. This was an early recognition of Indigenous relationships to land and of the collective nature of land distribution and management by Indigenous nations.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Treaties were made on Vancouver Island (sometimes referred to by the Crown as the Douglas Treaties) and in the immediate vicinity of lakes Huron and Superior. Later, in the later part of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, Treaties were made in the prairie region, northwestern Ontario, and the territories.

This patchwork quilt of Treaties was negotiated with the Queen to ensure safe passage for the railway, natural resource development, and settlement. All of this historic Treaty making took place after millennia of Treaty diplomacy amongst Indigenous nations.

Modern Treaties, which were made later in the twentieth century and which continue to be negotiated today, resemble contractual nation-to-nation agreements, rather than the relationship-building documents of previous centuries. These modern Treaties were a direct response to a 1973 Supreme Court of Canada ruling in the Calder case, which determined that Aboriginal title to land continued to exist where it had not been extinguished by the Crown.

Following the Calder case, the federal government developed a comprehensive land claims policy for the negotiation of Treaties where claims of unextinguished title to the land might be advanced. This policy exempted areas that were covered by previously negotiated Treaties, with the Crown claiming that those lands were previously surrendered.

This is in direct contrast with the Indigenous view of Treaties as agreements to share and to live in relationship on and with the land. Indigenous people have always contested strict Western legal interpretations of Treaties. They prefer to define and to implement them in accordance with Indigenous legal traditions and oral histories.

Courts have attempted to interpret and to define Treaties many times over. Through a series of cases that span a few decades, the Supreme Court developed principles for Treaty interpretation that view Treaties as unique agreements, or as solemn exchanges of promises, made by the Crown and Indigenous peoples.

Supreme Court justices have found that Treaties do not fit into international legal frameworks or regular contractual-type arrangements. In the Badger case, which concerned Indigenous hunting rights, the court said Treaties are “sacred promises, and the Crown’s honour requires the Court to assume that the Crown intended to fulfill its promises.”

In order to honour those sacred promises, the Supreme Court determined that ambiguities are to be resolved in favour of Indigenous people. Also, Indigenous understandings of words and legal concepts are to be preferred over more legalistic and technical constructions. Legal duties such as the honour of the Crown and fiduciary obligations should serve as protections to the solemn promises that were made during Treaty negotiations.

This same court has nonetheless enabled Treaty rights to be infringed upon, where the Crown can show that “broader societal” (primarily non-Indigenous) interests outweigh Indigenous priorities and perspectives. For instance, the court balances or “reconciles” the use of land for hydro-electric projects, oil and gas development, mining, and other activities where there has been prior Indigenous occupation of — and aspirations for — those lands.

Half a century ago, it was illegal for Indigenous people in Canada, including Treaty nations, to hire a lawyer or to bring a legal claim against the Crown.

Further, the courts have confirmed that Treaty promises were able to be unilaterally modified by the Crown prior to the 1982 constitutional protection. For example, commercial rights to harvest wildlife, which were negotiated as part of Treaty promises, were extinguished unilaterally by the Crown prior to their constitutional protection.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; text-align: justify; line-height: 14.1px; font: 14.0px 'Adobe Garamond Pro'; color: #47a58c}

Understanding Treaty relationships and promises requires applying both Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives. The oral histories of Treaty negotiations have a place in the Treaty interpretation process.

This presumed right to impact or to reduce the exercise of Treaty rights has been employed in the past by federal and provincial governments to limit access to hunting, trapping, fishing, and gathering areas.

These are important restrictions to many Indigenous people who continue to practise land-based and traditional lifestyles in their home territories.

They are also a direct affront to the promises of Treaty that aimed to preserve not only a way of life but also the autonomy and self-sufficiency of the Indigenous Treaty signatories.

There are some notable moments where Canadian law has been used to breach Treaty relationships. These include the creation of the Indian Act in 1876 (a mere five years after the negotiation of Treaty 1), and the pass system that was imposed by policy (but never legislated) and enforced by the North-West Mounted Police. Further, through legislation and the Natural Resource Transfer Agreements (NRTA), jurisdiction over natural resources in the West were transferred from the federal government to the provinces.

These agreements provided a right for First Nations to continue to hunt, trap, and fish for food but limited these activities to unoccupied Crown land and to land on which Indigenous people have a right of access. While the NRTA expanded the right to harvest beyond traditional or Treaty territory, it limited this right to subsistence — no commercial right could be claimed, even if this had previously been provided for in a Treaty.

What is particular about historic Treaty relationships in Canada is that they are founded in two distinct legal systems coming together to forge a relationship so that two parties could live well together within the same territory.

Understanding Treaty relationships and promises therefore requires applying both Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives. The oral histories of Treaty negotiations have a place in the Treaty interpretation process. The courts have indicated that strict rules of evidence have to be adapted to place oral history on an equal footing with historical documentation. They will consider the contextual factors that surrounded Treaty negotiations to determine the common intention that reconciled the interests of both parties at the time the Treaty was signed.

Many claims advanced by Indigenous people are met with strict legal interpretations of the Treaties, which generally state that the Indigenous nations agreed to “cede, release, surrender, and yield up” the land. However, the Indigenous legal concepts articulated by the Anishinaabe of Treaty 1, for example, show that the surrender of land is not possible when one is “made of the land” or “belongs to the land.”

This is a relationship of connection to land, rather than possession of it. There is no evidence that the idea of surrender was invoked at the Treaty negotiation itself, which leads to the conclusion that the Anishinaabe legal perspective should prevail.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada set out a framework for reconciliation that requires the revitalization of Indigenous law and legal traditions. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also recognizes Indigenous people’s laws, traditions, and customs. These Indigenous laws are essential to understanding how Indigenous people entered into the Treaty relationship with the Crown.

For example, when the Treaty commissioners and Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba entered into Treaty 1 negotiations with the Anishinaabe, they commended them for not participating in the Métis resistance, claiming that they would be rewarded for their loyalty to their mother, the Queen. Throughout the Treaty negotiations, the commissioner referred to Queen Victoria as a mother to the Anishinaabe, promising that she would treat all her children equally. The word for mother was easily translated between English and Ojibway, and the Chiefs responded that through the words of the Crown negotiators they could “hear their mother’s voice.”

The concept of a mother-and-child relationship was deceiving in this context. The Queen’s representatives would have understood the position of the child as one of subservience, of not being able to decide for themselves or to have any rights until the age of majority. The Anishinaabe, however, understood the mother’s role as one of extending kindness, love, and care for a child in a way that would foster the child’s autonomy and equality to all other children. This Anishinaabe perspective would align with a modern articulation of a sharing Treaty in which Indigenous self-determination is prioritized.

Treaties are law, both in the eyes of the Canadian state and within Indigenous legal systems. They are legal instruments that function as living, breathing affirmations of relationships between nations.

The law, however, as applied by Canadian courts and governments, has disproportionately been used to allow for the infringement upon and erosion of Treaties. This undermining of Treaty promises and disregard for Indigenous understandings of the Treaty relationship has persisted in Canadian law to the point where, in some cases, there is no longer a meaningful ability to exercise the rights the Treaties aim to protect.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples expresses the right of Indigenous peoples to have their Treaties recognized, observed, and enforced. In order to do so, Treaties must be placed in their historical, political, and cultural contexts. Although Indigenous people and nations continue to bring claims for breaches of the terms of Treaty (known as “specific claims” under Canadian policy), these claims are frustrated by government-imposed policies and evidentiary limits.

The greatest breach of Treaties, however, remains the inability of non- Indigenous governments to understand the fundamental relationship that Indigenous people have for millennia had with the lands and waters. Treaties were made in a sacred and spiritual way — with the help of the Creator, as a third party to the agreement — and the spirit and intent of Treaties is articulated through the understanding and application of Indigenous laws.

The law of Canada has been employed as a tool of dispossession in relation to Indigenous peoples, lands, and resources. Indigenous peoples view Treaties not as a fixed set of terms but rather as relationships of respect and reciprocity that are meant to be renewed. The Treaty relationship was meant to evolve over time, based on non-interference and respect for each other and for the land that was shared.

The importance of Indigenous laws in historic Treaty making has been misunderstood and undervalued, resulting in a very one-sided Eurocentric approach to Treaties. Possession, ownership, exclusion, and exploitation cannot define our relationships with the lands and waters.

We must today breathe life into the original intent of the Treaties. We must live well together, as our ancestors agreed, for as long as the grass grows, the sun shines, and the waters flow.

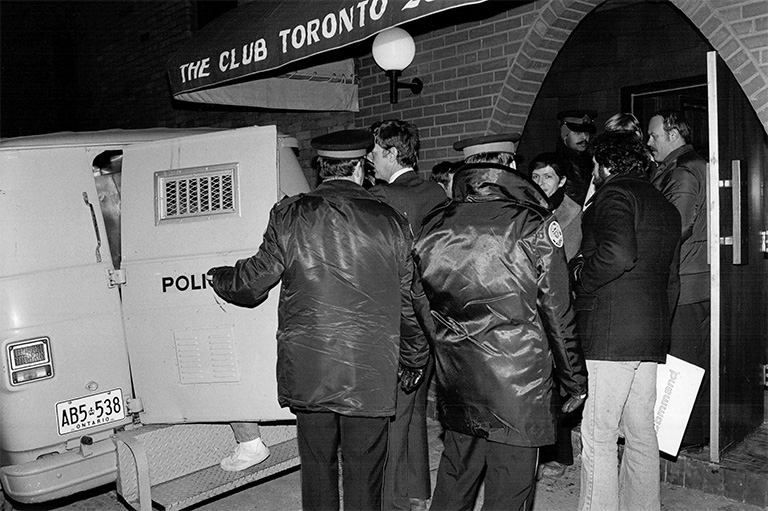

Treaty rights and wrongs

For centuries, Indigenous peoples have fought to maintain their cultures and ways of living in the face of attempts to force their assimilation into non-Indigenous society. These images depict the legacy of attempts to restrict the rights of First Nations peoples as well as moments when First Nations peoples have asserted their rights to build a better tomorrow.

-

An example of a pass issued under the pass system, enacted in 1885, which illegally restricted the movement of First Nations people living on reserves.Glenbow Museum

An example of a pass issued under the pass system, enacted in 1885, which illegally restricted the movement of First Nations people living on reserves.Glenbow Museum -

An unidentified First Nations farmer ploughs land in Western Canada, circa 1920. In the late-nineteenth century, the federal government attempted to force First Nations people in the West to settle on reserves and become farmers.Library and Archives Canada

An unidentified First Nations farmer ploughs land in Western Canada, circa 1920. In the late-nineteenth century, the federal government attempted to force First Nations people in the West to settle on reserves and become farmers.Library and Archives Canada -

Children at Fort Simpson Indian Residential School in the Northwest Territories hold letters that spell the word “Goodbye,” circa 1922. The trauma of the residential school system continues to impact Indigenous peoples today.Library and Archives Canada

Children at Fort Simpson Indian Residential School in the Northwest Territories hold letters that spell the word “Goodbye,” circa 1922. The trauma of the residential school system continues to impact Indigenous peoples today.Library and Archives Canada -

Gitxsan dancers perform outside the Supreme Court of Canada in 1997 as Gitxsan leaders inside argue the Delgamuukw case regarding Aboriginal title in British Columbia.The Canadian Press

Gitxsan dancers perform outside the Supreme Court of Canada in 1997 as Gitxsan leaders inside argue the Delgamuukw case regarding Aboriginal title in British Columbia.The Canadian Press

Register to receive your FREE educational package devoted to Treaties and the Treaty Relationship.

Packages are aimed at Grades 2–7 and Grades 7–12, and available in both English and French.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

More from the Treaties issue

These articles, as well as the corresponding educational resource package, can be found on the French side of our site.

Encouraging a deeper knowledge of history and Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

The Government of Canada creates opportunities to explore and share Canadian history.

The Winnipeg Foundation — supporting our shared truth and reconciliation journey.