Gakina Gidagwi’igoomin Anishinaabewiyang: We Are All Treaty People

In October 2017, twenty-one First Nations representing approximately thirty thousand people took the federal and Ontario governments to court, alleging that the Treaty commitments made by the man originally assigned to negotiate them in 1850, Special Commissioner William Benjamin Robinson, were due for renegotiation.

The case focuses on a central question: How should Treaty terms negotiated nearly 170 years ago be interpreted today?

The First Nations who signed Robinson’s Treaties argue that the federal and provincial governments have drawn considerable resource wealth from their territory without ever renegotiating the terms Robinson made, even though Robinson included a clause for renegotiation.

The annual annuity to band members remains the same today as it was in 1874 — four dollars per person.

Public commentary on the case has focused on the unreliability of the memories of Treaty signatories or their descendants, or on the idea that Treaties are somehow out of place in today’s world. These ideas reveal misconceptions within the public sphere regarding the significance of Treaties today.

Recovering the true spirit and intent of Treaties is a priority. These agreements are not old, obsolete, or pointless. First Nations’ own histories and accounts of Treaty processes uphold important principles of reciprocity, respect, and renewal rooted in thousands of years of experience and presence on these lands.

The Treaties hold the keys to a new path forward as living agreements regarding relationships between First Nations and settlers in the past, for the present, and towards the future.

The original spirit and intent of Treaty involves understanding and upholding the agreements people actually negotiated, rather than focusing on how Treaties have been reinterpreted long after the fact.

The misinterpretation of Treaties in general has generated a substantial body of case law in both the public and corporate sectors. The idea that First Nations then would want to clarify the original terms and ideas to which they agreed and ensure that they are honoured should not be viewed as an exceptional request.

Clarification is part of the process in all types of agreements, whether they are between nations, among businesses, or within individual contracts.

For First Nations people, the original spirit and intent of the Treaties was, and still is, centred on principles about land and nationhood that are embedded in ceremonies, protocols, and discussions of Treaties that are outside of the written documents themselves.

Even the courts recognize the negotiations prior to Treaty making, and the discussions afterwards, as being part of the Treaties. Therefore Treaties represent much more than the texts.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

According to Anishinaabe Elder Harry Bone in the radio series Let’s Talk Treaty, discussing the original spirit and intent of Treaty includes recognizing who First Nations are now and who First Nations were at the time of Treaty negotiation in relationship to settlers and to the land.

Bone, of the Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation in Manitoba, says First Nations are the first owners and occupants of the land; they protect their languages, beliefs, and teachings and honour the Creator. Treaties are part of the first law — the constitution of First Nations — that involves the idea of entering into peaceful arrangements with newcomers on an equal, nation-to-nation basis.

As a society, we find ourselves in a pivotal moment, and what we do next, with respect to Treaties as well as to the overall relationship between settlers and Indigenous peoples, will set the course for the future.

The intent of Treaties at the time of their negotiation was the protection and retention of rights to languages, ways of life, and existing belief systems. This undertaking is part of the original understanding of Treaty processes as ongoing relationships that are dynamic and adaptable.

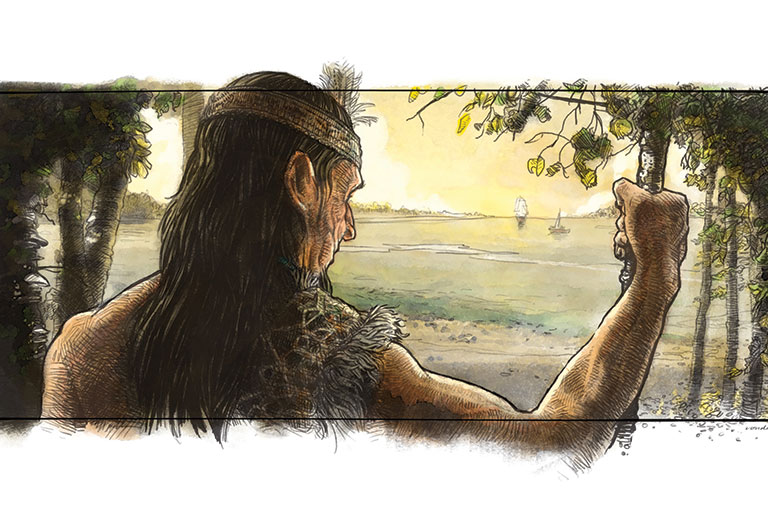

Treaties were about retaining a way of life that included hunting, fishing, and gathering, as well as a relationship to the land that existed for thousands of years prior to the arrival of Europeans. According to First Nations signatories of the Treaties, as well as to Knowledge Keepers today, the land and everything on it is alive.

The land has been described as the Creator’s Garden by Anishinaabe Elder Ken Courchene in Untuwe Pi Kin He: Who We Are, and the law is seen as Mother Earth herself. The seven sacred principles of Anishinaabe law, for instance, are centred on relationships — between nations, between individuals, and, most importantly, with the land.

At the time the Treaties were signed, as now, First Nations did not consider land to be a static entity to be bought or sold. It could not be distributed, parcelled out, and held individually in the sense of ownership.

As Anishinaabe Elder Lawrence Smith of Baaskaandibewi-ziibiing (Brokenhead) First Nation in Manitoba explains in Ka’esi Wahkotumahk Aski: Our Relations With The Land, the land and its resources are, and continue to be, gifts from Creator.

In the same volume, Anishinaabe Elder Francis Nepinak of Mina’igo-ziibiing (Pine Creek) First Nation in Manitoba describes oceans, lakes, and rivers as the veins of a human body, the plants like hair, and the ground like flesh.

And, as Indigenous legal scholar Aimée Craft writes in Breathing Life into the Stone Fort Treaty: An Anishinabe Understanding of Treaty One, this relationship between the people and the land means that they are inseparable, and that the land is a living entity that requires care for which the people are responsible.

Cree author Harold Johnson points out in Two Families: Treaties and Government that the land “is the place I belong to. This is where my ancestors are buried, where their atoms are carried up by insects to become part of the forest, where the animals eat the plants in the forest, and where my ancestors’ atoms are in the animals that I eat, in my turn. I am a part of this place. I do not say that I own this land; rather, the land owns me.”

Within this view, First Nations groups retain the primary attachment of their relationship with the land, regardless of any agreement they make to allow others to use it, Craft says in her book.

Being part of the land, they understand that they will continue to make decisions in regards to it. According to Elders, any relationship negotiated within the context of Treaty must adhere to these principles.

Agreements negotiated among First Nations groups engaged these kinds of ideas long before agreements were made with Europeans.

One example of this type of agreement is the Dish With One Spoon, a Treaty negotiated between the Anishinaabe and the Haudenosaunee. The dish represented territory the peoples shared in what is today southern Ontario, while the spoon represented the wealth of the land. The absence of a knife within this Treaty spoke to the need to maintain peace for the benefit of all.

Importantly, all participants in the agreement had the responsibility to ensure that the dish would never be empty by taking care of the land and of all of the living beings on it. The Creator and the laws were integral to the agreement. The Treaty was intended to last as long as the people lived on the earth.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The Dish With One Spoon Treaty was recorded like many others — on a wampum belt, which could be read as a way to remember the agreements made by previous generations. Instead of specifying concrete or specific terms in a timelimited way, these agreements established mutually beneficial and agreed-upon principles that were intended to last for many generations.

Each party had a responsibility to make sure that its actions conformed to the principles established in the Treaty. As a result, they were flexible agreements intended to maintain a spirit, rather than a strict set of rules that could not adapt to changing circumstances.

To generate a mutual understanding of the roles and responsibilities of each party, many groups called on the principles of kinship. As Anishinaabe Elder Barbara Rattlesnake, from Dootinaawi-ziibiing (Valley River) First Nation in Manitoba, maintains in Untuwe Pi Kin He: Who We Are, relationships are not limited to those people with whom a blood relation exists.

Under the Treaties, settlers and First Nations peoples could relate to each other as adopted relatives. For example, under the Two-Row Wampum, negotiated in 1613 between the Dutch and the Haudenosaunee in what is now New York State, the Dutch suggested that the Mohawk refer to them as fathers.

The Mohawk proposed an alternative relationship — brother — indicating a more equitable and autonomous relationship. The brotherhood was affirmed nearly 150 years later, in 1764, at the Treaty of Niagara, where over two thousand chiefs renewed and extended the Covenant Chain of Friendship, a multi-nation alliance between First Nations and the British Crown.

During the Numbered Treaty period, between 1871 and 1921, Crown Treaty negotiators used Indigenous kinship systems to their advantage to try to convey important principles. For instance, government negotiators made frequent references to the Great Mother (Queen Victoria) in their presentations to Anishinaabe people.

According to Craft, the more than 1,100 people gathered at Stone Fort (Lower Fort Garry near Selkirk, Manitoba) for the negotiation of Treaty 1 would have understood a mother figure as loving, kind, and responsible for protecting her children.

At the same time, the value of respect for the child meant that mothers encouraged children to make their own decisions about how they wished to live. As such, engaging the idea of the Queen as the Great Mother would have signalled to the Anishinaabe that the British Crown intended to deal fairly with them and to protect them without interfering in their affairs for many generations.

Treaty promises were made to last as long as “the sun shines, the grass grows, and rivers flow.” This refers to the land as well as to kin relationships, whether literal or figurative. In fact, many Elders have also suggested the term “waters,” which relates to the waters of a woman when a child is born.

As Johnson explains, settlers also became new relatives through Treaty. They became kiciwamanawak, or cousins, and are regarded by First Nations people as equals, not as superiors. First Nations assumed that Europeans would learn to live in balance with the land by watching Indigenous people, who had done so for thousands of years.

Johnson explains, “no one thought you would try to take everything for yourselves, and that we would have to beg for leftovers…. The Treaties that gave your family the right to occupy this territory were also an opportunity for you to learn how to live in this territory.”

This powerful reversal is essentially the crux of the issue: From the First Nations’ point of view, the Treaties granted Europeans access to the territory; settlers had the right to use some of the territory within the context of the Creator’s laws.

Misunderstandings were sometimes due to incomplete or inaccurate translations. As John S. Long reveals in Treaty No. 9: Making the Agreement to Share the Land in Far Northern Ontario in 1905, during the Treaty 9 negotiations translators referred to onaakonigewin, the closest Ojibway word for law.

Onaakonigewin refers to a decision necessary to achieving a good life, but not necessarily to an actual law as understood by Europeans. As Johnson proposes, “The authority assigned to the written text is a subversion of what really happened.”

This was demonstrated during the negotiation of Treaty 1, when the agreement recorded in writing on the ninth and final day of negotiations failed to register the complete agreement as it had been spoken and heard, Craft writes in Breathing Life Into the Stone Fort Treaty. In 1875, a second Treaty was negotiated with the same groups to reconcile these differences.

Government negotiators engaged First Nations ideas and protocols in their approach, providing some reassurance regarding respect and reciprocity.

For example, Alexander Morris, Treaty Commissioner at Treaty 6, explained to those assembled in 1876 at Fort Carlton, in present-day Saskatchewan, that what he was offering was not intended to take away from their mode of life, which they could enjoy just as they had before.

The presence of sacred objects during negotiations also reassured First Nations. As Nehetho Elder D’Arcy Linklater of Nisichawayasihk (Nelson House) Cree Nation explains in Dtantu Balai Betl Nahidei: Our Relations To The Newcomers, many sacred elements were used during the making of the Treaty, including the pipe, the tobacco, the stem, and the medicine.

Similarly, Anishinaabe Elder Florence Paynter of Sandy Bay First Nation in Manitoba describes the use of the pipe in Treaty ceremonies as a way of signalling the Creator’s presence and approval of the agreement.

In addition, Treaty medals — distributed at the signing of each Numbered Treaty — contained symbols of mutual benefit and respect. The medal’s main image depicted a military officer and a First Nations leader shaking hands over a buried hatchet — symbolizing peace and equality.

The background included the rising sun and several teepees — indicating that the people would be allowed to retain their own ways of life within a kinship relationship that would last for generations. Since the medal, as well as Treaty negotiators themselves, called upon natural elements with spiritual qualities, these agreements were perceived by First Nations signatories to be bound with their spirits for successive generations.

Elder Bone explains in Untuwe Pi Kin He: Who We Are: “You have to tie where our original rights came, and that is from the Creator.”

Instead of simply seeing two parties at the Treaty negotiations, then, we should see three: First Nations, settlers, and the Creator. The Creator’s laws framed First Nations’ understanding of and agreements to Treaty making. This kind of understanding is not a revision but rather a correction of a narrative written by non-Indigenous peoples that has failed to fully recognize the humanity of First Nation peoples and therefore their existence as nations with their own belief systems, ways of life, and governance structures.

Treaty agreements are not for the history books alone. Today the principle of free, prior, and informed consent animates political and cultural debates about land, appropriation, and other pressing issues. This principle requires that the relationships pursued today engage First Nations perspectives and priorities meaningfully and with consent.

A temporary exhibit at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg illustrates how Treaties are not being interpreted in ways that are true to their intent. Entitled Rights of Passage, it includes the story of Wasagamack First Nation in Manitoba, which in 2015 received a cheque in the amount of $79.38 to cover twenty years (from 1996 to 2015) of ammunition and twine as promised in the terms of their 1909 agreement to Treaty 5.

In 1908, this paltry sum might have ensured that band members could sustain their way of life, but it’s not what signatories envisioned would sustain their descendants a century later. The inadequate payment betrays the true intent and spirit of an agreement that was intended to provide for the peace and prosperity of many generations.

Treaties can be part of the foundational fabric of this society, but only if society embraces them for the agreements they were intended to be: agreements based on the principles of friendship, peace, and respect for all future generations.

As a society, we find ourselves in a pivotal moment, and what we do next — with respect to Treaties as well as to the overall relationship between settlers and First Nations peoples — will set the course for the future.

“To get to the future, we need a vision, then we must imagine the steps we must take to get to that vision,” says Harold Johnson, the Cree author.

“We cannot ignore our vision because it seems utopian, too grand, unachievable. Neither can we refuse to take the first steps because they are too small, too inconsequential…. We will both be part of whatever future we create, kiciwamanawak.”

Register to receive your FREE educational package devoted to Treaties and the Treaty Relationship.

Packages are aimed at Grades 2–7 and Grades 7–12, and available in both English and French.

Canada's History magazine was established in 1920 as The Beaver, a Journal of Progress. In its early years, the magazine focused on Canada's fur trade and life in Northern Canada. While Indigenous people were pictured in the magazine, they were rarely identified, and their stories were told by settlers. Today, Canada's History is raising the voices of First Nations, Métis and Inuit by sharing the stories of their past in their own words.

If you believe that stories of Canada’s Indigenous history should be more widely known, help us do more. Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share Indigenous stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

More from the Treaties issue

These articles, as well as the corresponding educational resource package, can be found on the French side of our site.

Encouraging a deeper knowledge of history and Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

The Government of Canada creates opportunities to explore and share Canadian history.

The Winnipeg Foundation — supporting our shared truth and reconciliation journey.