Klondike Women

Prior to her book Women of the Klondike being published in 1995, Frances Backhouse wrote an article for the December 1988-January 1989 issue of The Beaver magazine.

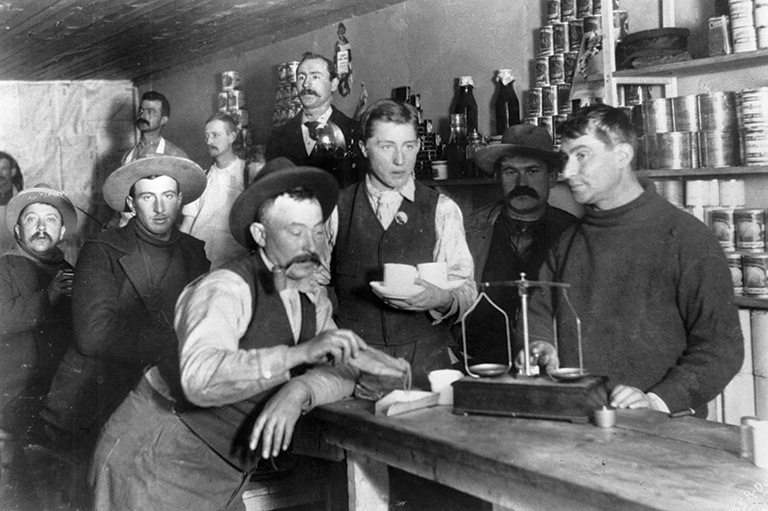

The story describes the women who sought their fortune in Dawson City, Yukon, at the height of the 1896–99 Klondike gold rush. Backhouse estimated that there were about five hundred women in Dawson City in 1898, out of a total population of sixteen thousand.

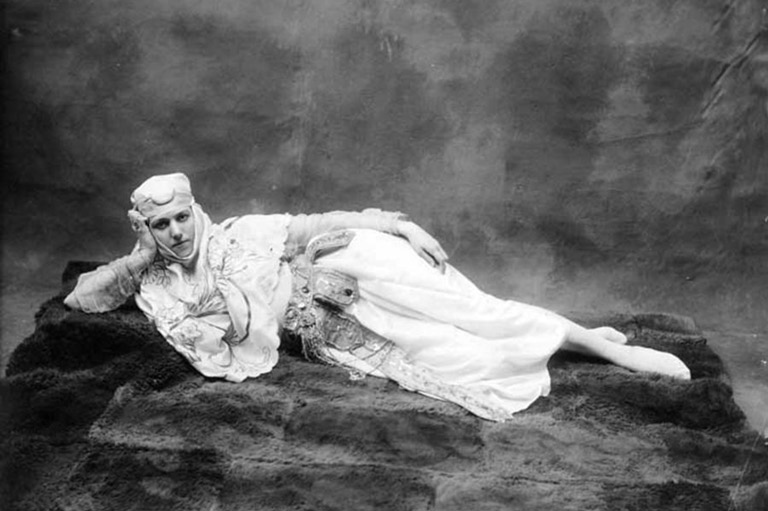

Some accompanied their husbands, while others were single. They worked as shopkeepers, cooks, launderers, dancers, sex workers, nurses, doctors, and gold miners. A few dropped in as tourists and newspaper reporters.

The Klondike’s womenfolk fell into one of three broad categories, according to Martha Black, one of the Dawson City residents quoted by Backhouse. At the bottom of the social ladder were prostitutes; in the middle were entertainers, such as cancan dancers; and at the top were the more “respectable” homemakers and small business owners like Black. An upper-middle-class woman from Chicago, Black left her husband to pursue adventure, fell in love with the North, and never looked back. She wrote about her adventures in her autobiography, My Ninety Years.

In contrast, life at the bottom was grim: “The veteran prostitutes knew what to expect,” wrote Backhouse. “They faced a high probability of dying young from venereal diseases, tuberculosis, malnutrition, or violence at the hands of pimps or clients.”

Dance hall entertainers fared better, with some, like “Diamond Tooth Gertie” Lovejoy, becoming famous. However, most burned out after five or ten years. “During the constant night of winter, drinking and dancing went on around the clock, and they had little respite from the revelry,” wrote Backhouse.

Among those engaged in more sober enterprises were the Catholic Sisters of St. Ann. They ran a hospital, where six nuns treated eleven hundred patients during a typhoid epidemic in 1898.

Few women actually toiled in the goldfields. An exception was Nellie Cashman. “Cashman, who was apparently single, had been a prospector for years before the Klondike gold rush and continued this life afterwards,” wrote Backhouse. Other women, like millionaire entrepreneur Belinda Mulrooney, hired men to do the back-breaking work of mining their claims.

“There were dozens of fascinating characters among the gold rush women, as well as many ordinary individuals,” wrote Backhouse. “They need not be glorified but they should be remembered.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!