On the Frontlines of Disaster

When Maj. Avery DeWitt arrived on the outskirts of Halifax on the morning of December 6, 1917, he was appalled by what he encountered. Where the thriving community of Richmond once stood, there was now nothing but hectares of blackened, smouldering rubble. Here and there, the skeletal remains of a church or factory loomed against the skyline.

Everything else was flattened. A dense layer of smoke blotted out the sun and an eerie silence hung over the ruins, punctuated now and then by screams and muffled cries for help. Up ahead, DeWitt saw dozens of badly injured men, women, and children being loaded onto a battered train, which sat idling on the tracks.

DeWitt, the physician at Camp Aldershot in Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley, had been en route to Halifax to attend a meeting that morning when the Mont Blanc, a French freighter carrying a lethal cargo of over twenty-five hundred tonnes of explosives in her hold, steamed into Halifax Harbour.

The First World War was in its third year and troops, supplies, and munitions from all over North America passed through Halifax on their way to the Western Front, making it one of the most vital ports in the British Empire. Traffic in the harbour was particularly heavy that morning, with more than forty-five vessels loading cargo, awaiting convoy, or being repaired.

As the Mont Blanc neared the entrance to the harbour at the Narrows, she met the Imo, a Norwegian ship carrying relief supplies for Belgium. The 5,041-tonne tramp steamer had strayed too far into the Mont Blanc’s water, putting the two vessels on a collision course. As the distance closed between them, the vessels attempted to manoeuvre around one another, but to no avail.

Spectators onshore watched in disbelief as the Imo rammed into the French freighter, cutting a three-metre gash in her starboard bow. A blaze broke out on the Mont Blanc’s deck, and, fearing for their lives, the captain and crew abandoned ship.

The burning vessel continued to drift down the harbour toward the city until it struck Pier 6. At approximately 9:05 a.m. the flames reached the TNT and other explosives in her hold, triggering the worst manmade explosion prior to Hiroshima.

Within moments, houses, schools, factories, and churches were reduced to rubble. Trains and vessels were demolished. Automobiles were hurled through the air like toys.

So severe was the blast that the Mont Blanc’s anchor shank, which weighed half a tonne, flew three-and-a-half kilometres across the Halifax peninsula, landing on the mainland side of the Northwest Arm, where it remains as a memorial to this day. One hundred and thirty hectares in Halifax’s north end were laid waste.

Dartmouth, directly across the harbour, was also in ruins. Approximately fifteen hundred people were killed instantly and nine thousand were injured. In the following days and weeks another five hundred perished as a result of wounds sustained in the blast. Hundreds of victims were buried beneath the wreckage, and fires raged throughout the devastated area.

When the explosion occurred, the Dominion Atlantic Railway (DAR) train on which DeWitt was travelling was far enough away that it wasn’t affected. But by the time it reached Rockingham, on the outskirts of Halifax, George Graham, the railway’s general manager, was waiting for it. Graham had been in Halifax when the explosion occurred.

When he discovered the telegraph and telephone lines were cut, and that the trains couldn’t get in or out of the city, he had rushed to Rockingham on foot — a distance of about six kilometres — to send out word of the disaster. Graham explained the desperate situation in Halifax to the passengers on DeWitt’s train and asked if there were any doctors, nurses, or Red Cross workers aboard. DeWitt immediately stepped forward.

The dark-haired thirty-six-year-old came from a prominent medical family in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. His father, Dr. George DeWitt, had received his medical degree from Harvard, and his sister, Nellie, was a nurse.

As a member of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, Maj. Avery DeWitt was better prepared than most civilians to deal with large-scale medical emergencies. However, with thousands in urgent need of immediate medical attention he, like every other physician in the area, would soon find his skills tested in ways he could never have imagined.

Graham put DeWitt on a locomotive, which took him to Richmond, where a train known as the Number 10 was idling on the tracks.

“The condition of the track and surrounding district was almost too horrible to describe,” DeWitt wrote in a letter to the Halifax Disaster Record Office. “Men, women, and children were lying round on the ground on boards, broken beds, doors, or anything they could get and suffering untold agonies. … With the help of several travellers, soldiers and train crew, we put about 112 cases on board the train.”

Conductor J.C. Gillespie was tremendously relieved to have a doctor to attend to the blood-soaked, shellshocked victims on board. As he ushered DeWitt through the cars, Gillespie described what had occurred on board earlier that morning:

The Number 10 was running behind schedule. It was just past Rockingham when the shock wave from the blast slammed into the train with what felt like the force of a torpedo. Screams filled the air as each of the windows shattered in unison. The cars tipped up, balancing precariously on one rail for a second or two before coming back to earth with a resounding crash.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Fortunately, the engineer was the only one aboard who was wounded — he had been hurled against the boiler head — and, despite his injuries, he insisted on remaining at the helm. Although slightly battered, the train was still operational — the only damage seemed to be the shattered windows — so they proceeded cautiously towards the city.

As they neared Richmond, the tracks, which were buried beneath tonnes of debris, became impassable. Minutes after the train came to a stop, hordes of ragged, bleeding, desperate people emerged from the ruins. Those who could walk stumbled toward the train pleading for help. Many were barefoot and far too scantily clad for the December chill.

As he later reported to the director of the Halifax Disaster Record Office, Gillespie was distressed by the sight of so many “cold, barefooted, and torn people.” Something had to be done to ease their suffering. He decided to take as many aboard as possible. “I went to work,” he said. “Filled the train full.”

As DeWitt surveyed the trainload of seriously injured victims who were eyeing him hopefully, he was thankful he’d grabbed his medical kit before leaving his home that morning. Although his scant equipment and supplies would barely begin to cover the countless injuries, it was better than nothing. As he later told the Halifax Disaster Record Office, “Fortunately, I had my hypodermic case, and morphine was a great blessing to many that morning.”

Doctors, nurses, Red Cross workers, medical students, and volunteers all across Halifax found themselves in similar situations that day. Shortly after the blast occurred, the wounded and dying flocked to hospitals and doctors’ offices. Before long, every medical facility was overflowing.

At that time, there were over a dozen hospitals scattered throughout Halifax and Dartmouth. All had sustained damage — windows had shattered, ceilings had collapsed, and plaster and debris had rained down on beds, operating tables, and equipment.

In addition, many of the hospitals were understaffed and ill-equipped. There were only three X-ray machines in the entire city. And the newly opened Camp Hill Hospital — built as a convalescent facility for returned soldiers — contained no surgical equipment whatsoever. Even basic necessities, such as hot water bottles, were in short supply, as were morphine, anesthetic, antiseptics, and sterilizing equipment. These shortages complicated an already critical state of affairs.

While doctors, nurses and volunteers grappled with the deluge of casualties that morning, city officials struggled to restore order. The situation was dire. Fires raged out of control, and the fire department itself was in shambles. Several of its members, including the fire chief, had been killed, and its only motorized vehicle had been demolished in the blast.

The police force was in little better shape. It lacked the training, equipment, and manpower to deal with a disaster of this magnitude. Added to this was the fact that twenty thousand people were suddenly destitute, homeless, and in need of shelter, food, clothing, and medical care.

Since Mayor Peter Martin happened to be out of town at the time, it fell to Deputy Mayor Henry Colwell to take on the unenviable position of authority that day. At 11:30 a.m., an emergency meeting took place between Colwell, Lieutenant Governor Mccallum Grant, former mayor Robert Macllreith, and a few members of city council. During this meeting, the groundwork was laid for the organization of rescue and relief.

One thing Colwell had working in his favour was the fact that about five thousand sailors and soldiers were stationed in the city at the time. Therefore, control of the search-and-rescue operation was turned over to the military.

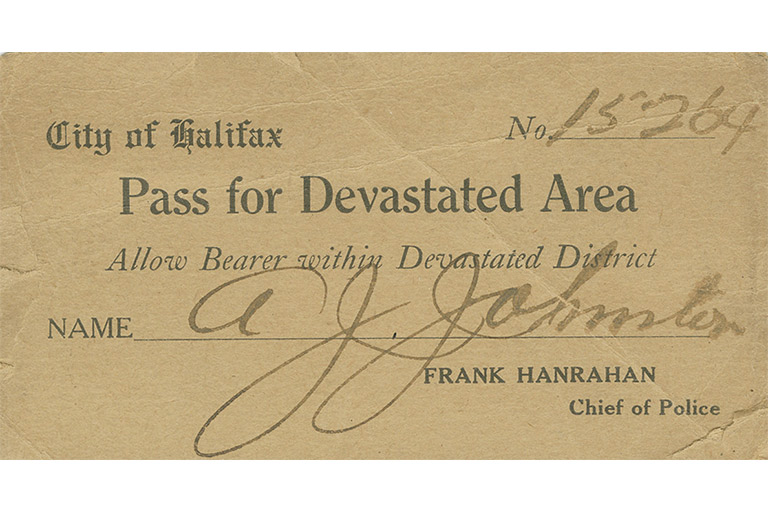

Before long, an armed guard was posted around the devastated area — only those carrying official passes were permitted to enter — and search parties began systematically combing the ruins for victims. All vehicles were commandeered for transporting the wounded to hospital.

Not long after the search-and-rescue effort got underway, word spread that the military magazine at Wellington Barracks was thought to be on fire and another explosion imminent. Panic ensued.

Soldiers went door-to-door, telling everyone to head for the open spaces at the Commons near downtown and at Point Pleasant Park on the southern tip of the Halifax peninsula. Streams of bloodied and traumatized people fled from the devastated area. Hundreds of those trapped beneath the ruins were left behind to perish in the fires.

Although many doctors and nurses ignored the evacuation notice and continued working, others stopped what they were doing and transferred their patients out to the relative safety of open spaces. In Dartmouth, Dr. M.S. Dickson’s house was filled with wounded people seeking medical attention that morning. Annie Anderson, a medical student who boarded with Dickson, described the scene to the Halifax Disaster Record Office:

“The injuries were head gashes and cuts about the eyes. Saw one woman with her face cut open, and the froth oozing through a cut in the windpipe. She had been cut by heavy plate glass in a shop where she worked.”

Dickson was in the midst of amputating an arm when the warning of a second explosion went round. With the help of Anderson, he moved his operating table and the houseful of badly wounded patients out to the street.

There, he completed the amputation and continued to patch up an endless stream of casualties until he was informed the crisis had passed and he could move his operating theatre back inside.

By 1:00 p.m. there wasn’t space aboard the Number 10 train for a single extra casualty. After filling up with water and coal at the roundhouse, conductor Gillespie decided to take the trainload of injured to the town of Truro, 100 kilometres north of Halifax. There, he was certain the victims would be sheltered and cared for.

By that time, word of the disaster had spread across the country and into the New England states. Boston, as well as the Nova Scotia communities of Wolfville and New Glasgow, organized relief trains to deliver badly needed doctors, nurses, and medical supplies to the beleaguered city.

At Windsor Junction, about 15 kilometres from central Halifax, the Number 10 met the train from Wolfville bound for Halifax. Since there were more casualties aboard the Number 10 than could be dealt with by a single physician, a doctor and nurse from the relief train transferred to the Truro-bound train. Gillespie set them up in a car at the opposite end of the train from DeWitt, and they continued on their journey.

The relief train from Wolfville was the first to arrive in Halifax, at about three o’clock that afternoon. Lt.-Col. Frederick McKelvey Bell, head of the medical committee, met the doctors and nurses on the edge of Richmond and directed them to city hall, where they would be detailed to a hospital. Since the roads in the devastated area were largely impassable, they were forced to walk some distance before being met by a fleet of cars.

The doctors and nurses picked their way through mountains of debris that contained overturned carts, smashed automobiles, dead horses, and horribly mutilated corpses. Every so often they came across piles of blackened and twisted bodies, stacked like cordwood, awaiting delivery to the morgue. Many of the returned soldiers who worked in the ruins that day stated that the gruesome sights they witnessed in Richmond were as bad as, if not worse than, anything they’d seen at the front.

The scenes in the hospitals were almost as horrible. Camp Hill Hospital, a simple, two-storey structure on the corner of Robie Street and Jubilee Road in Halifax, was designed to house a maximum of 280 patients. That day, its wards, corridors, dining room, kitchen, offices, and closets were crammed with fifteen hundred critically injured people. A steady stream of stretcher bearers delivered load after load of wounded. Mattresses lined the floors and everyone had to step carefully to avoid tripping over the patients.

The multitude of filthy, blood-soaked victims appeared to one Sister of Charity as “shapeless masses of gore … the clothes stiff with blood, or with blood and water, as many had been taken from the harbour.” Adding to the chaos were the dozens of people wandering from ward to ward in search of missing loved ones. Hundreds of children were separated from their parents that day, many never to be reunited.

Since the regular operating room in Camp Hill had not yet been fitted up, doctors performed surgery wherever they could find space. Temporary operating rooms were set up in the kitchen and dining room.

The doctors operated on kitchen tables, and, in many cases, were forced to use kitchen utensils in lieu of surgical tools. And when surgical thread ran out, they resorted to using ordinary cotton thread to stitch up the wounds.

The variety and severity of wounds suffered in the explosion were extraordinary. Third-degree burns, fractures of all kinds, amputated limbs, gashes, facial lacerations, and eye injuries were widespread. Flying glass and shrapnel left many horribly disfigured.

The Halifax Disaster Record Office recorded the observations of Florence J. Murray, a medical student who volunteered at Camp Hill Hospital: “Saw one woman lying with her face cut off. It was lying on the left side like a trap door. The face had been cut across the forehead, round the cheek and to the corner of the mouth. … The nasal and frontal bones were cut away and the base of the brain was exposed. … This patient died.”

In almost every case the wounds were packed with dirt, plaster, cinders, and glass, making the onerous task of patching them up that much more difficult.

Maj. DeWitt also faced grievous injuries needing immediate attention — and his situation was complicated by the fact that he was on a moving train, with the only surgical equipment available to him being a pair of scissors and forceps.

DeWitt had no choice but to attempt to remove the damaged eyeballs of two critically injured patients. With the help of two assistants, DeWitt managed to complete the enucleations successfully. However, any feeling of satisfaction he may have derived from performing this tricky operation in such difficult circumstances, was, no doubt, overshadowed by the fact that three other patients aboard the train — all children — died before they reached Truro that day.

The Number 10 train finally reached Truro at four o’clock that afternoon. Since Truro had no hospital, the courthouse, academy, and fire hall had all been converted into temporary hospitals. But the doctors and nurses in the area had all departed for Halifax, leaving only DeWitt and the other doctor aboard to continue caring for the casualties.

It wasn’t until DeWitt was overseeing the unloading of his patients that he actually met the other doctor, as well as the nurse who had been working at the other end of the train.

When he discovered who they were, he was astonished — it was his father, Dr. George DeWitt, and his sister, Nellie, who had come aboard the Number 10 at Windsor Junction that morning.

But they had little time to marvel at this unusual turn of events. Like doctors, nurses, and volunteers all over Halifax, the DeWitts worked day and night for the following week without a thought for themselves.

As word of the disaster spread, aid began pouring in from across Canada and the United States. Medical units from Rhode Island and Massachusetts, as well as doctors and nurses from various parts of Canada, arrived in Halifax to lend much-needed assistance to the first responders. Despite this generous outpouring of aid, it would be months before a semblance of normalcy returned to the city, and years before the scars would finally begin to heal.

Identifying the Dead

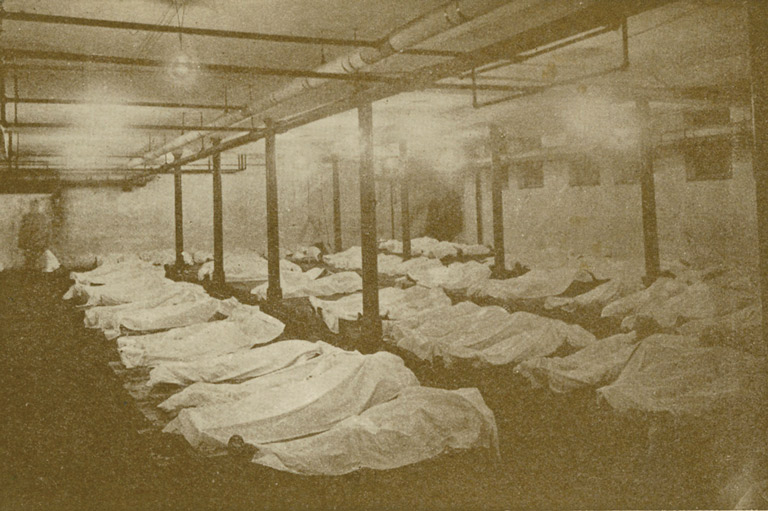

One of the greatest challenges officials faced in the wake of the Halifax Explosion was that of dealing with the overwhelming number of bodies. Since many who died in the explosion were disfigured or burned beyond recognition, identifying the victims required some knowledge for forensic identification techniques.

As chance would have it, just five years earlier the Titanic had gone down off the coast of Newfoundland. Afterwards, hundreds of the bodies were brought to Halifax for identifications and burial.

Robert MacIlreith, who had been mayor at the time of the Titanic disaster, had learned a great deal about forensic identification from that experience. This knowledge proved invaluable with dealing with the explosion’s casualties.

MacIlreith instructed those involved in the search and rescue to tag each body recovered from the ruins. These labels bore the name of the street, and, where possible, the number of the house where the body was found. Any personal effects discovered near the bodies were also collected.

From the Titanic experience, MacIlreith knew that the handful of private undertakers’ morgues in the city would be quickly overwhelmed by the multitude of bodies recovered from the ruins. Therefore, a temporary morgue would be necessary. He selected the basement of the Chebucto Road School, which was on the edge of the devastated area, for this purpose.

R.N. Stone, an embalming professor from Toronto, and A.A. Schieter, an undertaking expert from Kitchener, were placed in charge of the mortuary. Soldiers delivered the bodies to the morgue, where they were then stripped and washed. All clothing and personal effects were removed and placed in cotton bags. Each bag was given a number, which corresponded with that on the body. Often these personal effects were the only means of identification.

Blinded by the Blast

Of all the injuries sustained in the Halifax Explosion, eye injuries were by far the most prevalent. Throughout the city people had flocked to windows to watch the spectacle of the blazing vessel in the harbour. When the explosion occurred, every window for kilometres around imploded. Glass shards left 593 people with critical eye injuries. Almost half of them needed one or both eyes removed.

Soon after arriving at Camp Hill on the evening of the day of the explosion, Dr. George Cox, a forty-six-year-old ocularist from New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, had rounded up enough eye patients to keep him busy for several days.

The injuries, Cox later recorded in his notes, incuded eyelids that were “cut into literal fringes” and glass-studded eyeballs that appeared to be nothing but “bags of glass.” In many cases “there were no more eyeballs. It was as if the ball had been laid open and then stuffed with pieces of glass or sometimes crockery, brick splinters, and on palpation, they would clink,” Cox wrote.

For the next five days Cox did nothing but “patch up eyes,” only stopping to rest when he was forced to remove both eyeballs — “or rather, what was left of them.”

Was it Sabotage?

Rumours of sabotage by German agents were rife after the Halifax Explosion. With Canada engrossed in the First World War, and German submarines lying close to Halifax Harbour, the wartime adage “Loose lips sink ships” was on everyone’s mind.

Two days after the largest man-made explosion the world had ever seen, the Halifax Herald declared: “Behind [it] all, as responsible for the disaster, is that arch criminal, the Kaiser of Germany, who forced our empire and allies into the fearful war.”

One widespread rumour suggested that the captain and pilot of the Imo were murdered by a crew member just before the collision with the Mont Blanc. This could have allowed a German spy on board to orchestrate an accident in the harbour. However, a lone witness on the bridge of the Imo, helmsman John Johansen, said that the captain had given all commands and signals.

During the inquiry that followed the explosion, officers from the harbour offices revealed they had received calls from people asking the locations and movements of individual ships. Newspaper headlines expressed the public’s outrage the next day: “Secret News Sent by Public Phone.”

In 1922, rumors erupted again when Dr. Samuel Prince, author of a sociological study of the explosion, declared that sabotage was a real possibility.

But the hearings and inquiries into the cause of the explosion provided no definite answers. And to this day, no one is entirely sure what happened on the bridge of the Imo that fateful December morning.

— Christopher Webb

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!