The Halifax Explosion: Canada's Worst Disaster

On December 6, 1917, Canada faced its worst disaster on home soil during the First World War — and it happened not due to an enemy attack but as the result of an apparently avoidable accident.

Halifax was Canada’s largest East Coast port and one of the most vital in the British Empire during the war. Soldiers and materials from across the country passed through on their way to Europe and the Western Front.

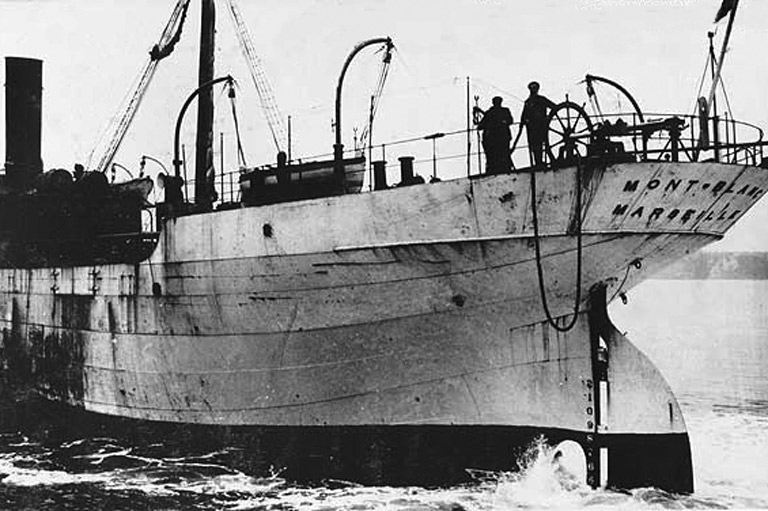

On the morning of December 6, in Halifax Harbour, the French freighter Mont-Blanc, loaded with more than 2,500 tonnes of explosives, neared the Imo, a Norwegian ship carrying relief supplies destined for Belgium. The vessels were on a collision course, and their crews were unable to avoid an impact that cut a huge opening in the Mont-Blanc.

When the freighter caught fire, its captain and crew abandoned the ship, which drifted until it collided with a pier. As onlookers watched in amazement, flames reached the explosives in the Mont-Blanc’s hold, triggering an explosion that destroyed large parts of Halifax and, across the harbour, Dartmouth.

Photographs portray Halifax after the catastrophe, as well as the beginnings of the recovery efforts. And, in an excerpt from his new book, The Halifax Explosion: Canada’s Worst Disaster, Ken Cuthbertson explains the devastation that occurred in the minutes immediately following the explosion.

‘A sound for God to make, not man.’

The hands of the Citadel Hill clock read 9:04 a.m. That was the exact moment of the great Halifax harbour explosion of December 6, 1917, which was destined to be the deadliest disaster in Canadian history. A primitive seismometer located in the basement of the old physics building at Dalhousie University recorded the event. However, the dispassionate scientific data — a few squiggly lines scratched on graph paper by a machine more than three kilometres from ground zero — told nothing of the human story of that fateful day: fear, horror, heartbreak, and drama.

The blast that obliterated the Mont-Blanc, claimed about two thousand lives, and devastated the city of Halifax was the most powerful “man-made” explosion in history, a distinction it held until the development of atomic bombs in 1945. Its reverberations shot through the soil, granite, and Precambrian slate bedrock beneath Halifax at a speed of more than 6.5 kilometres per second. That is twenty-three times the speed of sound.

The thunderclap that accompanied the explosion echoed up and down the length of the harbour channel. It boomed across the city of Halifax and neighbouring Dartmouth, and it was audible much farther away.

The crew of the American cruiser the USS Tacoma heard the boom eighty kilometres out to sea. The warship’s lookout had just sighted on the horizon the Devil’s Island lighthouse, nineteen kilometres southeast of the entrance to Halifax harbour. “At 9:05 heard heavy explosion in general direction of Halifax, observed great clouds of smoke high in air,” the officer on watch recorded in the ship’s logbook.

The same rumble that drew the attention of the Tacoma’s crew was audible as far away as Cape Breton Island, two hundred and seventy-five kilometres to the northeast. In Truro, ninety-five kilometres north of Halifax, the blast’s concussive shock broke some windows and shook a clock off the wall in the railway dispatcher’s office. As one observer said, the rumble of the Halifax explosion was “a sound for God to make, not man.”

The great Halifax harbour explosion of 1917 unleashed the energy equivalent of three kilotonnes of TNT. When detonated, one tonne of TNT releases about a billion calories of heat energy. Kilo being the Greek word for “a thousand,” it follows that the calories of heat released in the explosion of one kilotonne of TNT is a thousand times a billion. A trillion calories.

The destructive power of a shock wave as intense as the one the Halifax harbour explosion generated is terrifying. On a bright, sunlit day, it is invisible, yet it can send human bodies and objects as big as a house flying like dry leaves in a gale. It can crush a person’s internal organs, rupture eyeballs, and shatter eardrums. It can snap trees, lampposts, and telephone poles. It can level buildings that are close to ground zero, while those farther away that remain upright still see their doors blown off their hinges, roofs destroyed, and windows shattered; glass shards from broken windows fly like tiny arrows that maim, blind, and kill as they sever heads and limbs.

The pressure generated by the chemical reaction in the Mont-Blanc’s cargo hold amounted to thousands of “earth atmospheres” — the 14.70 pounds per square inch (psi) air pressure that is normal at sea level. (By comparison, the pressure at the wreck site of the Titanic, four kilometres deep, is about 6,500 psi.) At the same time, the air temperature flared to about 5,000 degrees Celsius, which is almost as hot as the surface of the sun, and hot enough to vaporize the Mont-Blanc.

-

The Mont-Blanc, which was vaporized by the explosion.Library and Archives Canada

The Mont-Blanc, which was vaporized by the explosion.Library and Archives Canada -

The Imo, which was hurled against the Dartmouth shore.Library and Archives Canada

The Imo, which was hurled against the Dartmouth shore.Library and Archives Canada -

View of Halifax after the explosion, looking south, December 6, 1917.Library and Archives Canada

View of Halifax after the explosion, looking south, December 6, 1917.Library and Archives Canada -

A photograph of the blast, taken about twenty-one kilometres away.Library and Archives Canada

A photograph of the blast, taken about twenty-one kilometres away.Library and Archives Canada

Just as a stone dropping into the still waters of a pond creates rings of disturbance, the destructive shock wave of the explosion surged outward for more than a kilometre in all directions and launched skyward molten remnants of the ship’s hull and its cargo. Some bits of this shrapnel were as large as a refrigerator; others were the size of marbles. All were lethal, ripping into human flesh, slamming into wooden buildings, or perforating metal ships.

A piece of the Mont-Blanc’s five-hundred-kilogram anchor soared through the air for four kilometres before it crashed through a roof. The ship’s 90-mm aft deck gun ended up near a small lake on the Dartmouth side of the harbour, five kilometres from ground zero. A large chunk of metal from one of the Mont-Blanc’s boilers smashed into the Royal Naval College of Canada, coming to rest in a lecture hall, where it flattened the master’s dais and several student desks. Fortunately, the room was empty at the time.

The heat of the explosion that obliterated the Mont-Blanc superheated the water around and under the ship, gasifying the sea to the harbour floor, six metres beneath. As water rushed in to fill the vacuum, it threw up a tsunami. The massive wall of water nine metres high raced across the harbour to Dartmouth. It also roared up and down the harbour channel and far out into the Atlantic. In the confined space of the harbour, the impact was murderous. The tsunami battered ships, swamped boats, and tossed vessels of all sizes up onto the shore. It dragged people to their deaths when it washed over piers and sped waist-deep along streets on both sides of the harbour. “[The tsunami] boiled over the shore and climbed the [Fort Needham] hill as far as the third cross-street [Albert Street], carrying with it the wreckage of small boats, fragments of fish, and somewhere, lost in the thousands of tons of hissing brine, the bodies of men,” [wrote Hugh MacLennan in Barometer Rising].

Even then, the murderous wave was yet wreaking havoc. On its retreat, the water snatched up still more debris along with the bodies of explosion victims, some alive, others dead. And with them it carried off personal property, vegetation, animals, and the remains of crumpled homes and workplaces. There was still more misery to come.

In the wake of the tsunami’s retreat, a towering cloud of noxious gases … drifted over Halifax. “For ten minutes after the explosion a ‹black rain” was observed to fall from the sky. This was an oily soot, the unconsumed carbon of the explosives. It blackened clothing almost like liquid tar,” recalled Archibald MacMechan, the Dalhousie English professor who would become the “official historian” of the explosion. “It blackened the faces and bodies of all it fell on. … It penetrated clothing to the skin and coated the ruins of the houses, until the snow and rain storms washed it away.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.