Vikings on a Prairie Ocean

As mediator, I work in the space where big problems meet big organizations with many diverse players, all of them connected in one way or another to a problem. Interests, values, and power collide, often in the vortex where the economy, the environment, and society intersect. I am the man in the middle helping to resolve deeply embedded differences. So why would a guy like me start writing about a group of Icelandic immigrants living along a prairie lake?

My writing was born out of nostalgia. Often, after a particularly stressful day at work, my mind would drift back to my time growing up in a fishing family on Lake Winnipeg. The rich memories were like comfort food, often eliciting laughter or tears. Over time, I began to write down the stories of the people and places I had known as a boy.

I didn’t know it then, but, like Bilbo in The Hobbit, I was beginning a great journey that would, over the course of several years, culminate in my recently published memoir, Vikings on a Prairie Ocean: The Saga of a Lake, a People, a Family and a Man.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The story of Icelandic settlement along Lake Winnipeg began in the 1870s, when the government of Sir John A. Macdonald was trying to solidify Canada’s hold over the newly acquired North-West Territory, which included most of the land north and west of current-day Ontario. Sturdy settlers were needed to fill this territory.

Lord Dufferin, Canada’s third post-Confederation Governor General, believed Icelanders would fit the bill. Dufferin had visited the island in 1855. In his 1856 Letters from the High Latitudes he described the islanders as a hardy people with “an almost miraculous exuberance of mental powers.”

Dufferin urged Macdonald to invite the Icelanders to settle in the West. A plan was devised to create an “Icelandic Reserve” along nearly 130 kilometres of the western shore of Lake Winnipeg. This area was at that time part of the District of Keewatin that extended north of Manitoba — then just a postage-stamp-shaped province extending only fifty-eight kilometres north of Winnipeg.

Advertisement

The first Icelanders arrived in 1875. My family arrived the following year. These first immigrants were impoverished sheep farmers whose grazing lands in Iceland had been destroyed by volcanic eruptions. Buoyed by the promise of a new life in New Iceland, they were greeted upon their arrival by intolerable cold and snow, deadly smallpox, tormenting mosquitoes, and near starvation. Many settlers left after just a few years.

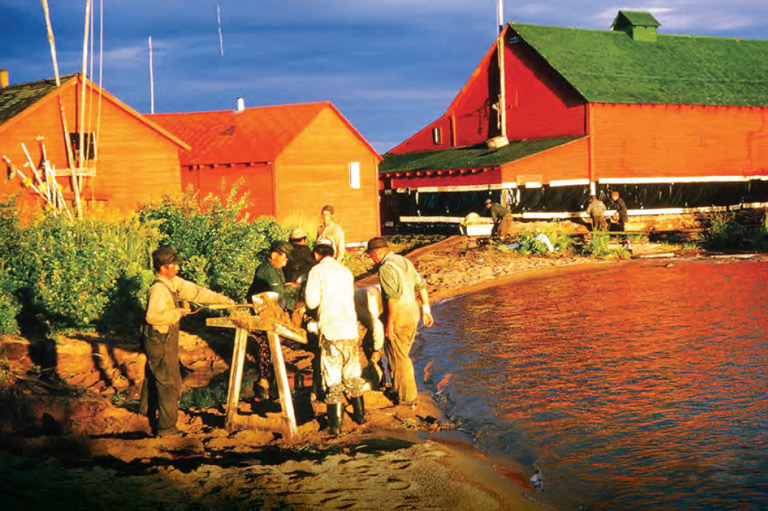

Thank God for the fish. A few fish pulled through a hole in the ice of Lake Winnipeg staved off starvation during my family’s first winter, spent in a shack on Hecla Island, about three hours drive north of modern-day Winnipeg. By 1882, my great-grandfather and his brother had hauled in the first commercial catches of fish near Hecla.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Soon, this colony of sheep farmers turned fishermen was selling its catches in Chicago and New York. News of Lake Winnipeg’s bounty lured more Icelanders to Manitoba. My ancestors emerged as leaders in the blossoming community.

In writing my memoir, I came to realize just how much I had been shaped by my heritage. The Icelanders understood that to make a life in this rugged land they would need to resolve their differences and work together. They would need to forge relationships with the First Nations as well as with the merchants and businesspeople to the south. Gradually, they established local governance, launched a newspaper, organized churches, and set up schools.

As someone who worked for years as a lawyer representing First Nations impacted by Manitoba’s hydro developments and also by mercury contamination of rivers flowing into and out of the lake, the story of New Iceland’s cooperation with local First Nations was inspiring. These early settlers were the epitome of what it takes to build a sustainable future. Their story gave me new insights into connecting the past, the present, and the future.

The Icelandic diaspora has spread across North America since those early days along Lake Winnipeg. However, all of its members still find their place and identity lodged in that “prairie ocean.”

And, each year, many return home to celebrate Islendingadagurinn — an annual Icelandic festival held in Gimi, Manitoba, each August — where they rekindle friendships and refresh their roots.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!