Tailor Made

It was September 23, 1972, and twenty-eight-year-old Lydia Peralta stood in the airport in Manila, preparing to board her flight to Canada. Her family had travelled for hours from their farm in the northern Philippine province of Pangasinan to see her off. Waiting in line along with twenty-two other women recruited by the Winnipeg clothing manufacturer Silpit, she opened her passport to check her visa — only to notice that the name on the document was not her own. She felt a wave of panic. At that moment, another woman in the group raised her voice: “Who is Lydia Peralta? Why is her visa in my passport?” The recruitment agency had evidently mixed up their paperwork. Relieved, Lydia retrieved her visa and boarded the plane.

Four days earlier, twenty-six-year-old Helen Padua had left on the same journey from the Philippine capital. Although she grew up just one town apart from Lydia, the two women didn’t know each other; they would meet, and become friends, only after settling in Winnipeg. But similar circumstances motivated both of them to leave their homes and families: Determined to escape from the traditional roles imposed on women in provincial Philippine society, they sought independence and financial stability by pursuing their ambitions beyond their native country.

By leaving when they did, the two women narrowly missed living under the military dictatorship of Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos. The day after Lydia’s plane took off, Marcos declared martial law — a situation that lasted for the next fourteen years.

Although their lives diverged in many ways, both Helen and Lydia benefitted from a program that, from 1968 to the 1980s, offered thousands of Filipina clothing workers a rare opportunity to immigrate to Canada, which would have been difficult — if not impossible — through other channels.

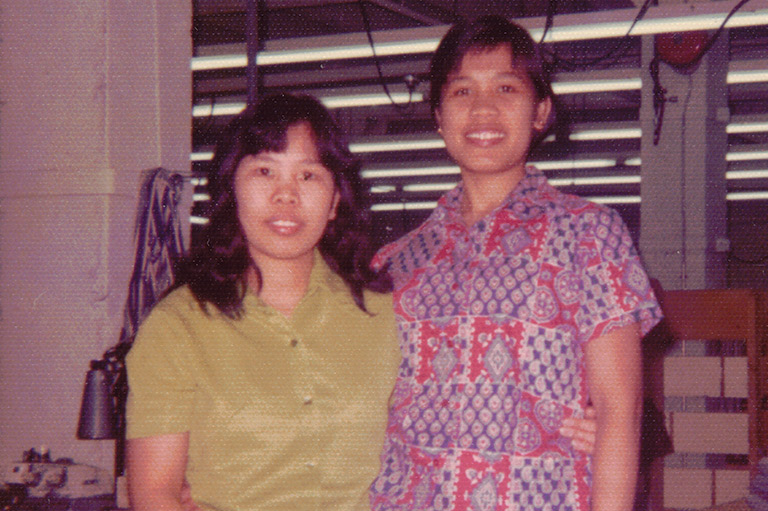

In the history of the Filipino community in Canada, the garment industry looms large, demonstrating the relationship between labour needs and immigration policies. However, the industry formed just one aspect of its workers’ lives in Canada, and sometimes not an important one. To Lydia and Helen, both now senior citizens, what is most important is their sense of accomplishment and joy at the homes and families they have built. Their contributions to Canadian society extend far beyond their early years working in clothing factories.

Article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Helen and Lydia came of age in the 1950s and 1960s during a period of postwar reconstruction in the Philippines marked by economic growth that would falter by the early 1970s. Both lived modest, hard-working lives on farms, and were exposed early to the traditional roles of women in provincial life. Lydia’s parents died when she was young, forcing her to leave school and take on domestic responsibilities, such as housekeeping, for her older sister. As she grew older, her siblings expected her to stay home and marry.

Helen encountered similar pressures. Although her parents valued education, there were few professions deemed respectable for women. Initially, she pursued a nursing degree, but the disapproval of her father and brothers forced her to withdraw from the program. She spent a miserable year working in her family’s fields. “Oh my God, it’s so hard,” she recalled in an interview in 2024. “All the jobs in the field I did. ... You’re out there, yeah, rain or shine.”

At the end of that year, her father presented her with two options: remain a farmer or attend school to become a teacher. Teaching was one of the few socially acceptable careers for women, as it aligned with traditional expectations of them as nurturing, mother-like figures responsible for raising and morally guiding children. Bowing to her father’s wishes, she enrolled in a teaching program in a local university.

The rapid growth in consumer and material culture that democratic states like the Philippines experienced during the postwar period was particularly strong in urban centres. Because this growth was slower to reach rural regions, the allure of city life loomed large for young people. “I’m so ambitious,” Lydia recalled. “I said, I don’t want to live in the province. ... I don’t want to live as a farmer. ... And I said, if I go to Manila, I will work in there.” She chuckled, adding: “My dream is, I have my purse with me, going somewhere else like that.”

When she was in her mid-twenties, Lydia moved to Manila without her family’s support — a significant act of defiance against traditional patriarchal life trajectories. She found employment at Philippine-American Embroidery, with little thought of eventually emigrating. For her, the move to the capital was about attaining personal independence, rather than pursuing life abroad.

In contrast, Helen’s move to Manila was driven by a clear goal: to develop the skills necessary for employment overseas. After finishing her teaching degree, she visited Manila for a one-week holiday to see her brother and sister-in-law, Benigno and Estelita Naron. While the prospect of life as a provincial teacher felt stifling, Manila was a place that “looked like the future,” she recalled. She longed for what Benigno and Estelita had: their own home and the financial stability to afford the things they wanted.

Helen’s brother and his wife encouraged her to consider working abroad. She knew that the garment industry in Canada was hiring Filipinas, and working for Estelita, who owned a small dressmaking shop in their home, would give her the experience needed to apply. Still, her decision to move to Manila and work as a dressmaker, instead of a teacher, did not go over well with her remaining family in Pangasinan: “[My brother] is mad because of — what is the use of graduating, if you don’t use it, you know?” she remembered. “And I said, in the first place, I told you already that this is not the right course that I want.”

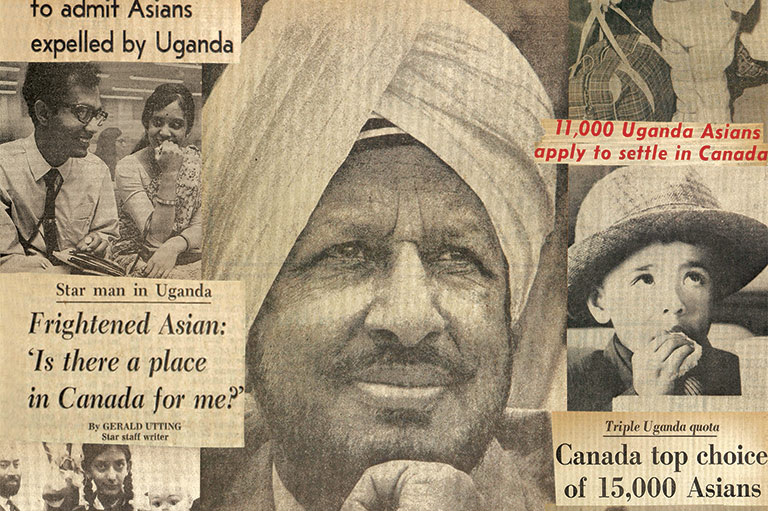

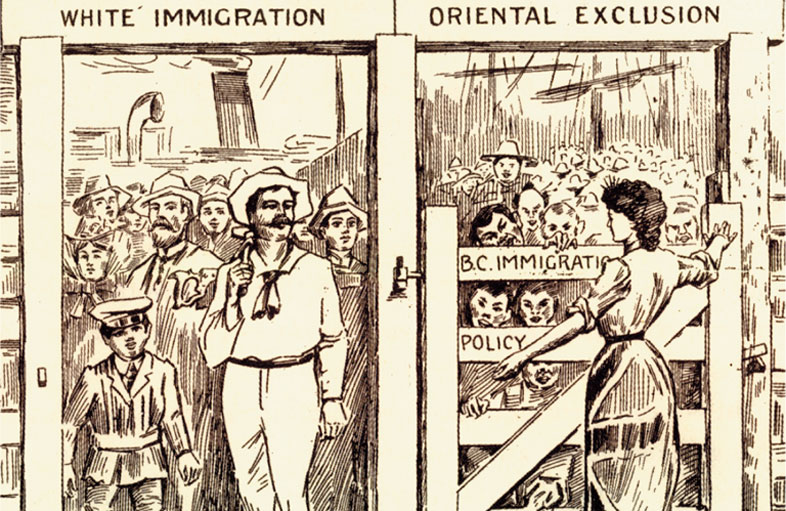

Canada’s immigration system underwent a major overhaul in 1967, replacing discriminatory race- and country-based restrictions with a points system that assessed applicants based on education, profession, language ability, and wealth. This happened at a fortuitous time for garment workers and manufacturers.

Since the end of the Second World War, Canada’s clothing industry had relied on foreign labour, because local workers found the jobs undesirable. By the 1960s, Canada’s clothing-and-textile industry was booming. But as businesses expanded, factories faced chronic labour shortages, compounded by the declining flow of workers from traditional southern-European sources like Italy.

Winnipeg had 5,200 textile workers employed in various factories, and it was estimated that hundreds more workers were needed, while demand would only grow. The need was immediate, as Winnipeg companies estimated they were working at fifty per cent of their capacity and losing hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of business as a result.

Correspondence between industry leaders and government officials reveals that, in 1968, they were looking to the Philippines — which already had a thriving garment sector — as a potential replacement source for labour. Working with provincial and federal governments, garment manufacturers in Winnipeg set up recruitment schemes in Manila, offering jobs that came with permanent-residency status.

In October 1968, the first wave of Filipina garment workers arrived in Winnipeg, a city that throughout the 1960s and 1970s would absorb thousands of these workers due to its acute labour shortages. Estelita Naron went to Canada on this program in 1971 and found employment at Westcott, a clothing factory in Winnipeg. As a floor supervisor there with some influence, she was able to secure a job offer for her sister-in-law Helen the following year without an interview, providing her a smooth path to permanent residency. Still, it entailed personal sacrifices: Helen had to leave behind her sweetheart, Lino Padua, because the immigration program only accepted single people.

While Helen’s family was sad to see her leave home, even her father recognized the benefits that moving to Canada offered: “If you’re going to stay here, you have no life here,” she recalled him saying.

Without a family connection to help her get a job, Lydia had to pass through the formal application procedure to take part in the immigration scheme. She first heard about two visiting Canadian recruiters from her co-workers in Manila. By that time, she had three years of experience using high-speed modern sewing machines — one of the key skills the recruiters sought.

When Lydia arrived at the hotel where the recruitment was taking place, she found the waiting room filled with other women, some quietly anxious, others chatting nervously. Five hours later, when her name was finally called, she entered a small room where one Canadian and one Filipina recruiter awaited her. Lydia completed the sewing test in just ten minutes.

After the test, Lydia felt a surge of anxiety. Her future seemed to hinge entirely on this opportunity. Without a strong educational background, she feared she might not stand out. However, she was confident in her sewing skills, had a working knowledge of English from caring for her cousin’s children while he served in the U.S. Navy, and possessed a fierce determination to improve her life. While working abroad had not been in her long-term plans — and she had recently met her future husband, Manny Cansino, while on a bus ride home to Pangasinan from Manila — passing the test to become a garment worker set her on a path toward a new future.

Advertisement

When Lydia landed in Winnipeg, she was surprised to find a welcoming party of dozens of people waiting for her. It had become the custom for Filipina garment workers who were already in Winnipeg to greet new workers at the airport, often accompanying the representatives of the companies that recruited the women.

A manager from Silpit divided the new arrivals into two groups: those who had family or friends to pick them up and those whose living arrangements had been organized by Silpit. Like many clothing workers, Lydia received a loan from Silpit to help with her initial costs in Winnipeg. The loans — usually around $150 to $200 — were forgiven over two years, as long as the worker stayed with the company. This system, along with the company’s role in arranging living accommodations, eased a precarious part of the immigration process. It allowed Filipinas who might not have been able to save for their first few months — especially given the high costs of immigration paperwork — the opportunity to move to Canada.

The week after Lydia arrived, the city was hit by a snowstorm. She still remembers her amazement at the “smoke” that came out of her mouth in the cold air. One of her fondest memories of those first days and weeks was playing outside in the snow with her new friends and co-workers. “I could only see snow in the fridge, you know, the freezer,” she said. “But when I came here, it’s real.”

Even though she didn’t have family to welcome her to Canada, Lydia didn’t feel lonely. She was surrounded by Filipinas at work and in her apartment building, which was largely rented by Silpit employees.

“They’re friendly ... even though you don’t know [them],” she recalled. She lived with four other young Filipinas and quickly made more friends at work. Her days cycled between home, work, attending church, grocery shopping, and sometimes walking downtown with her friends to shop, or just window-shop, at The Bay or Eaton’s.

For Helen, the experience of settling in was somewhat different. She had a smaller social circle and spent more time at home, since her brother and sister-in-law were protective of her activities. She noticed that Winnipeg often seemed to have empty streets, while in the Philippines there were always people milling around outside. The sun sat low on the horizon in these northern latitudes, and it didn’t shine as brilliantly as in the tropics. Christmas, especially, felt cold and lonely compared with Pangasinan, where community festivities began in September and ran through December.

Still, the city’s growing Filipino community provided opportunities for social connection. At a house party thrown by one of the garment workers, Helen met Lydia, and they bonded over their common roots in Pangasinan. Two years after emigrating, both women returned to the Philippines to marry their sweethearts, in weddings that took place within weeks of each other. By 1975, their husbands had joined them in Canada.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Although their sewing skills gave them entry to Canada, many of the immigrants recruited through the garment-worker program left the industry after a few years, largely due to working conditions and pay. Lydia, like most other workers, was paid per item completed, whereas Helen worked for a standard hourly wage because she liked earning a predictable paycheque that didn’t depend on the pace of her sewing. Lydia quit her position at Silpit after the company tried to lower her piecemeal rate, because she worked so quickly that her earnings were too high. There were so many jobs available at the time, she noted, that “if you quit this morning, afternoon you got a job.” She worked for a few years in another clothing factory before leaving the industry entirely.

Helen left Westcott after being offered a lower wage increase than her co-workers. She spent a few years working at a candy factory before returning to the textile business at Dominion Tanners, where she worked with her husband, Lino, and Lydia’s husband, Manny.

For Lino Padua, the adjustment to Canada was difficult. After arriving, he lived with Helen in her brother’s basement, where he felt like a prisoner. “I was thinking Canada is very rich,” Lino remembered. “That’s what I have in mind. How come I live like in … a cell prison?”

But soon the isolation eased as Lino found work and they moved into their own home, had children, and gradually sponsored many of their own siblings to live in Winnipeg.

Now, Lino declares his happiness in Canada, especially with his sons and their families. “They’re good sons,” he said with pride. “They are very close [to each other].” He’s not sure they would have enjoyed the same quality of life in the Philippines. “I guess I don’t think so ... because my surrounding [here] is not as much crime as over there, especially back in the north where I came from.”

Like Helen and Lydia, many Filipina garment workers had boyfriends, fiancés, or even husbands and children before immigrating to Canada, but they did not disclose this to government officials. “They make a lie just because, well, you cannot blame them,” Lydia explained. “They lie just because [Canadian government officials] want single people to come over here.” However, after becoming established in Canada, these women often sponsored their husbands, parents, siblings, and the families of their spouses.

Government sources suggest that the Filipino population in Canada prior to the influx of clothing workers was around eight hundred. Determining the number of Filipina garment workers who landed in Canada in the 1960s and 1970s is challenging due to limited specific data, but information on broader trends during this period is available. By 1969, 3,001 Filipinos had immigrated to Canada. Nearly three thousand more were entering annually by 1972, with around one hundred thousand living in Canada as permanent residents or citizens in 1979, according to government records.

In Winnipeg, garment workers built upon a relatively small foundation of health-care professionals to create larger, more robust Filipino communities. The Winnipeg population was celebrated in 1979 when the city was twinned with Manila, a relationship that continues today. As of the 2021 census, more than 950,000 people of Filipino origin lived in Canada — and many can trace their roots back to a pioneering Filipina immigrant.

This was an era in global migration when women, rather than men, increasingly took the lead in initiating immigration, as Lydia and Helen did. Though their new lives came with struggles, they also brought the independence the women desired — an independence that, today, has become a hallmark of their success.

It’s New Year’s Eve 2024, and eighty-year-old Lydia Cansino is sitting in the living room of her home in Winnipeg. The deep dark of the winter night is held back by lights blazing within the house, the silence of the cold outside overcome by laughter and shouts. Lydia misses the warmth of the Philippines but, if she hasn’t come to like the cold of Canada, at least she’s used to it. Surrounding her are three generations of family, most of whom are in Canada because of her decision to leave the Philippines in 1972.

She and her family are playing a Filipino New Year’s Eve game called sabog, where she, as the host, tosses coins for kids and adults to catch. Lydia’s wit is sharp, and her jokes delight. She is often seen socializing with her friends and family and playing games, like the Filipino card game tongits — in fact, she is known to her close friends as the “Tongits Queen of Manitoba.”

Historians sometimes look for grand narratives in topics such as the impact of the garment industry on women’s lives. But Lydia and Helen’s stories demonstrate one thing: that their experiences working in clothing factories did not define their identities or their lives in Canada. Working in their trade was just the first of many steps taken to find happiness in this country. It was the means through which they came to Canada to create the richer narratives of home, family, and success in life. “Even for me, I don’t have much education. I have money here and I could buy what I want,” Lydia reflects. “For me, I’m so happy that I am here. I’m so blessed that I am here.”

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement