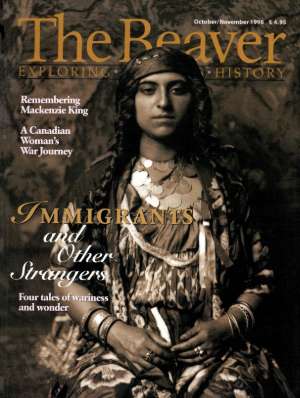

The Roma in Peterborough

In Peterborough, Ontario, in the early summer of 1909, each evening the Evening Examiner reported, “literally thousands of people” visited the Roma encampment, some arriving in carriages, others in automobiles, the rest on foot, to stand and watch while the Romany women went about the ordinary business of preparing supper. Some of the women were not amused being gawked at and threw water and boiled rice at the spectators, but Rosie, styled by the Peterborough newspaper as “the Gypsie Queen” and reportedly all of fourteen years old (and very self-possessed), ordered the offenders to stop, and they did.

Article continues below

-

The Romany children intrigued the people of Peterborough, who rushed to get a glimpse of the strangers in their midst.Frederick Lewis Roy

The Romany children intrigued the people of Peterborough, who rushed to get a glimpse of the strangers in their midst.Frederick Lewis Roy -

The Roma, or gypsies as they were called then, travelled by horse-drawn wagon in 1909.Frederick Lewis Roy

The Roma, or gypsies as they were called then, travelled by horse-drawn wagon in 1909.Frederick Lewis Roy -

Romany men pose for the photographer.Frederick Lewis Roy

Romany men pose for the photographer.Frederick Lewis Roy -

"The women present a fantastic appearance to say the least," wrote the Peterborough Evening Examiner.Frederick Lewis Roy

"The women present a fantastic appearance to say the least," wrote the Peterborough Evening Examiner.Frederick Lewis Roy -

Stephen George claimed to be chief of three tribes of approximately fifty people each. He was the father of Rosie, “the Gypsie Queen."Frederick Lewis Roy

Stephen George claimed to be chief of three tribes of approximately fifty people each. He was the father of Rosie, “the Gypsie Queen."Frederick Lewis Roy -

The Roma travelled by horse-drawn wagon in 1909.Frederick Lewis Roy

The Roma travelled by horse-drawn wagon in 1909.Frederick Lewis Roy

The Peterborough townspeople, including photographer Frederick Lewis Roy, whose pictures accompany this article, studied the women whose flowing, brightly coloured garments and abundance of jewellery they deemed fantastic; they noted the children, “practically naked” and permitted to smoke cigarettes; they commented on the food — “a funny smelling stew” that “would hardly commend itself to the average person.” Finally, as night fell, a local police constable arrived to drive back the crowds to allow the Romany people to sleep in peace. The Romany women had no male companions to help them in the task of securing their protection because, unfortunately, all the men, including their chief, Stephen George, were in Peterborough county jail charged with the offence of loitering on the roadside and obstructing passengers in a public highway and the offence of allowing vehicles to stand on the road in the township of Smith for a period of more than three hours.

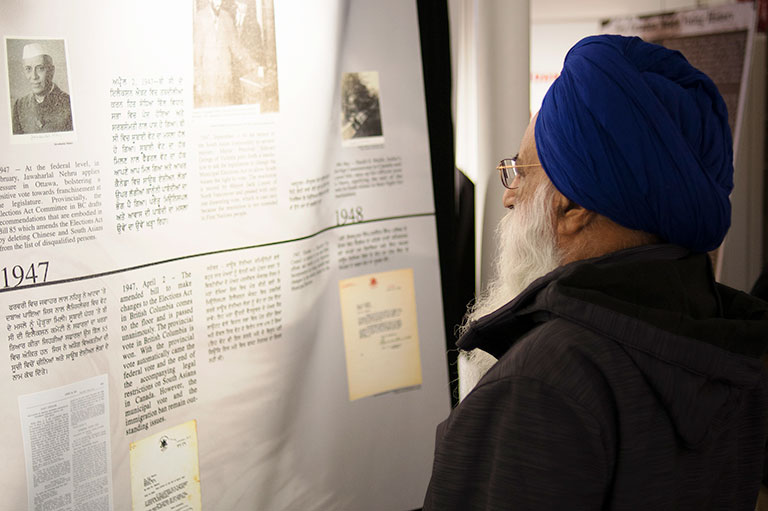

It was an old tune to the Roma, a stateless minority of some twelve million people. Throughout their thousand-year diaspora, as they moved ever westward from their roots in India, to western Europe in the fourteenth and fifteen centuries, to the Americas in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Roma have been considered either exotic or dangerous, creations of a romantic imagination or convenient scapegoats, admired or reviled; in most cases, wholly “other” — strangers in whatever land they happen to dwell.

In its most virulent forms, persecution of the Roma had led to enslavement by the princes of medieval Romanya, decreed hangings of all Roma over age eighteen in King Frederick William’s Prussia, and mass death in the Nazi concentration camps. Lately, in post-Communist Eastern Europe, Roma have undergone renewed attacks and evictions, oppression that has been not without consequence to Canada. Late in the summer of 1997, about 1,000 Roma from the Czech Republic tried to emigrate to Canada after a film on Czech television depicted Canada as a haven. Two months after the film’s showing, Canada re-imposed visa requirements for Czechs, effectively reducing Roma refugee claimants to a trickle.

Mercifully, the reaction of the Peterborough townspeople in 1909 to the strangers in their midst was comparatively temperate. But, as newspaper accounts of the day indicate, the reaction nonetheless honed to the stereotypes that have been the Roma’s constant companions for a millennium — attraction, wonder, criticism, and distrust.

Canada may be a multicultural society today, particularly in its larger cities, but in 1909 Canadians were more provincial than cosmopolitan, more openly biased than politically correct, and each social grouping more protective of its niche in society. Outsiders, whether geographical, religious, or cultural, were openly declared so, their alien status often supported by policy and enforced by law.

I asked a 102-year old friend of mine if he remembered the Roma. ”Oh yes“ he replied. ”Everyone was afraid of them, but ... I went up to the jail and talked to them.“

The Peterborough of 1909 was a town of fewer than 20,000 citizens, most of them of English, Irish, and Scottish descent living at a time before the advent of cinema, radio, and television. The arrival of the Roma must have been the most exotic event of the decade for people who had to depend on their own resources for entertainment.

I asked a 102-year-old friend of mine if he remembered the Roma. “Oh yes!” he replied. “Everyone was afraid of them, but they wouldn’t hurt anyone. I went up to the jail and talked to them.”

Peterborough jail was home to the Romany men for more than a week. Frequently referred to in newspaper copy as Mexicans because they were believed to have originated in Mexico, the Roma had been under the keen eye of various regional authorities for some time as they travelled eastward through southern Ontario. “The Mexicans have terrorized the countryside,” the Evening Examiner declared in its Tuesday, June 22, 1909 issue under the headline, “Gypsy Captives Are a Picturesque Lot”: “all along the line they have caused trouble and annoyance, and the authorities have done well to round them up instead of merely driving them on to other fields of prey.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

With their men in jail, the Romany women and children were detained in the jail’s courtyard. But after a couple of days, after the men did not plead to the charges at their first court appearance and were remanded in custody until the following week, the civic leaders decided to let the women and children leave and look after themselves, as the cost of feeding sixty people, thirty horses, and assorted dogs, as well as hiring special constables, was thought too great a burden on taxpayers. The leaders also contacted Ottawa to ascertain if the Roma could be deported to Mexico, but they were told the Roma were naturalized Canadians and deportation was impossible.

As the caravan of fifteen wagons, women, and children moved down one of the main streets to a vacant lot at the edge of town, it caused “a sensation as it passed,” according to the newspaper. A circus ground was the allusion chosen by the reporter to describe the encampment the Roma made on the town’s outskirts. It was here the people of Peterborough gathered in great numbers — like a circus crowd — to observe the social behaviour of their itinerant guests.

As to put a finishing touch to so Eastern a picture, a beautiful girl, gold bedecked and scarlet clad, rose up and in a graceful, languorous manner began to dance, chanting the while and moving her arms in time with the music.

Anything that appeared to veer from the norms of life as lived by the average Peterborough citizen caught the eyes of reporters and was diligently recorded, whether the subject was braided hair, necklaces of coins, children and dogs sleeping together, or women smoking pipes. One woman, Mrs. MacFarlane Wilson, writing in the Toronto Globe, described the men as “disreputable looking” but the women as “beautiful, of a rich ruddy brown complexion, black hair, dazzling white teeth, and those mournful stag-like black eyes which seem to denote past tragedies.” She continued:

There were no Madonna-like faces, no curves or dimples, but features clearly carven like cameos, and, as Romany blood is gentle blood, their hands and feet were slim and small.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

She was describing a wedding party. After a week of incarceration, the men were brought to a packed courtroom of spectators. The magistrate seemed to embody the contradictory response of Peterborough to the Roma: he found several of the men guilty as charged but thought further imprisonment ineffective. He released the prisoners on payment of a $125 fine (a considerable sum in 1909) and a promise to leave Peterborough at once. But he expressed sympathy for the Roma (“They had not had proper bringing up ...”) and granted them a three-day reprieve so that the queen, Rosie, Stephen George’s daughter, could be married to a man named Stoke, described as “an extensive land-owner in the far west.”

Mrs. Wilson was captivated by the life and colour of the wedding, the climax of nine days of novelty for Peterborough, the scarlet dresses worn by the women, the bride’s light chintz-like silk with yards of pink muslin, the flowers in her hair floating down her back, the free spending on food, the kegs of ale, “and even telegraphing.” She added:

As to put a finishing touch to so Eastern a picture, a beautiful girl, gold bedecked and scarlet clad, rose up and in a graceful, languorous manner began to dance, chanting the while and moving her arms in time with the music.

If some of the Peterborough region’s farmers and shopkeepers had felt aggrieved by the presence of the Roma, if civic officials were quick to prosecute, their feelings were not universally shared, even in establishment quarters. None other than the band from the local 57th Regiment played the dance music for the wedding.

The Ottawa Children's Aid Society was summoned when someone thought two of the children had skin too fair for Roma.

The next day, the Evening Examiner reported, the Roma “folded their tents like the Arabs” and were gone, bound for Ottawa. But interest in their movements did not abate immediately. The Peterborough newspaper continued with a stream of stories as the town’s former guests progressed by caravan through eastern Ontario. The Roma were ordered to decamp from a hamlet about two or three days journey down the road by men armed with dogs and guns.

They were accused of robbery in Ottawa. Attempts were made by authorities to drive them out of Hull, Quebec, where they were seen bathing near their encampment “in a half-naked condition.” A kidnapping charge was levelled against two Romany men, then dismissed. The Ottawa Children’s Aid Society was summoned when someone thought two of the children had skin too fair for Roma. (The children proved to be those of Stephen George.) Wherever they travelled, rumours and accusations accompanied them, and more often preceded them. It was the old tune. Played again and again.

“No One Is Sorry,” the Evening Examiner declared in the subhead to its July 3 account when the Roma left Peterborough, but the content of the story somewhat belied this claim. “The authorities will not be sorry that the strange visitors have left,” the paper stated, “although the public will miss an attraction that never seemed to lose interest for them.”

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement