From Head Tax to Hockey Heroes

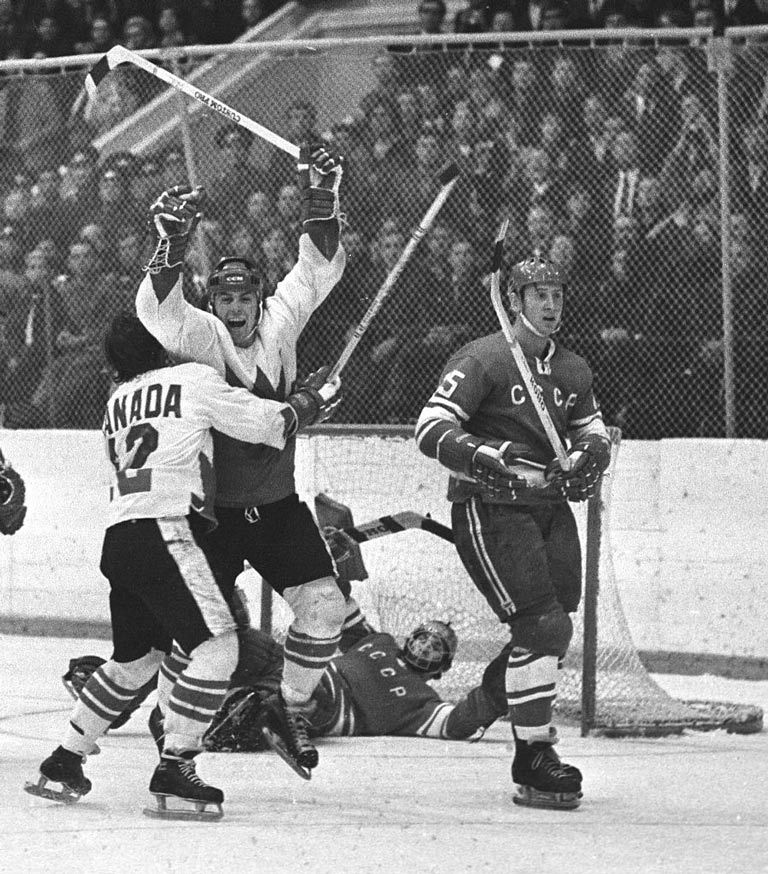

When Rose Chin gave an eight-year-old Paul Henderson a pair of hand-me-down skates, she didn’t know that this boy, a classmate of her son Alan, would go on to famously score three winning goals in the 1972 Canada-Soviet Summit Series. What she did know was how it felt to go without as a child and how hockey was helping her family weave itself into the fabric of a Canada rife with anti-Chinese racism.

It was 1951, and the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 (also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, see “Acts of discrimination”), had been repealed only four years earlier. Its dissolution, however, had no immediate impact on long-standing anti-Asian attitudes. From the 1858 arrival of Chinese gold miners in British Columbia to laundry and head taxes, the message was clear: Chinese were not welcome. In the village of Lucknow, Ontario, however, the Chin family story was different — in large part because of brothers Bill, Albert (Ab), and George.

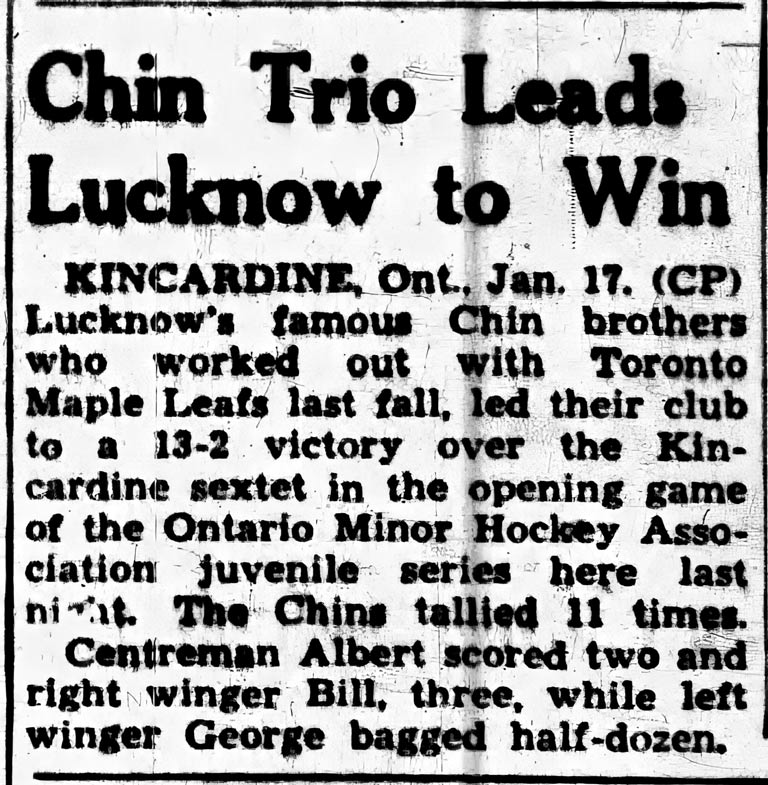

For a sizable stretch of the 1940s, the trio was an on-ice force to be reckoned with. Still, small-town Ontario newspapers like the Sault Star dug into stereotypes, describing them as “The Flying Chinese.” The Detroit Free Press’s discrimination was more overt. “There’s a line playing for Lucknow, Ont., in an amateur loop composed of the Ching [sic] brothers,” it reported in 1944. “Even if those fellows can’t play hockey, we can use them to do the laundry and cooking.” Locally, however, they were the hometown hockey prodigies of Charles and Rose Chin, the owners of the popular Chin’s Restaurant on Main Street.

article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

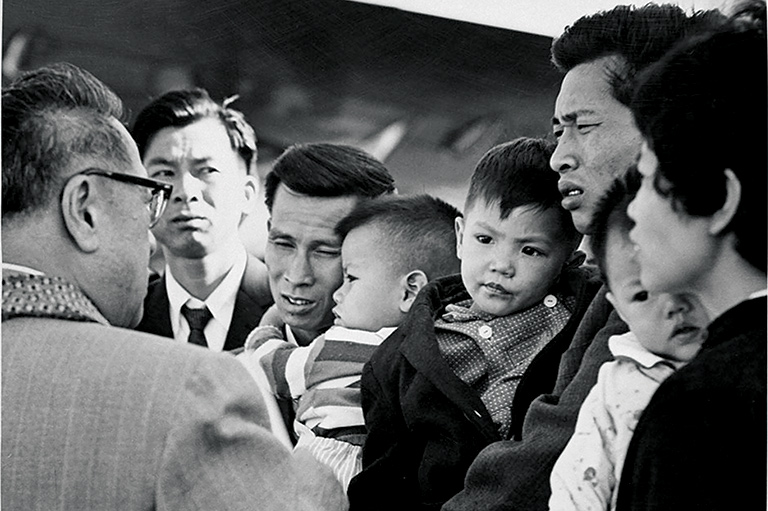

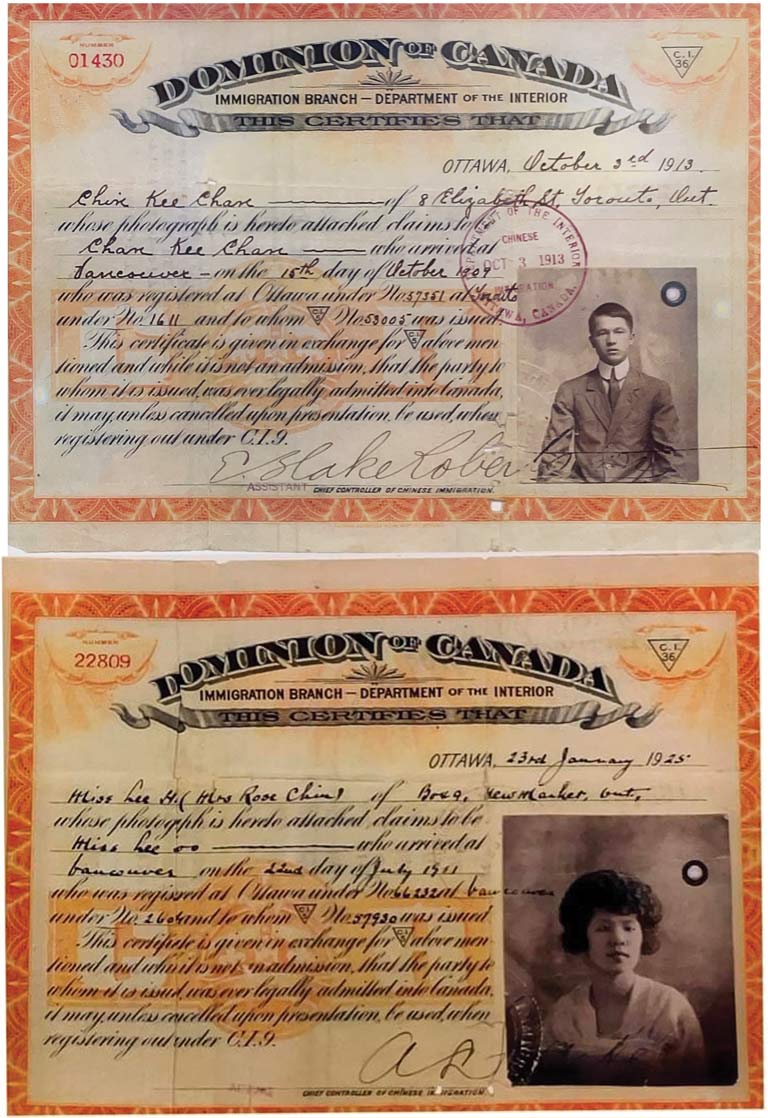

Rose — born Lee Gun Ho — was brought to Vancouver from China in 1911 at age six by her deceased father’s relatives, Lee Ying and his wife, Lee Hong Shee. They found her a job as a mui tsai (servant girl) for a wealthy Chinese immigrant family. When Rose was seventeen, Mrs. Lee took her to Toronto for an arranged marriage with another Chinese immigrant, Charles Chin.

Charles — born Chin Kee Chan — was seventeen when he arrived in Toronto in 1909. He worked in the laundry business together with his father, who had immigrated to Canada in 1903, paying the one-hundred-dollar head tax.

Charlie and Rose’s first child, James Fook Sun Chin, was born in 1922 in Newmarket, Ontario, a town about fifty kilometres north of Toronto, where Charlie was working at a cafe owned by his father. Over the next nineteen years, the couple had thirteen more children: Harry, Sam, Frank, Bill, Ab, George, Mary, Margaret, Morley, Gladys, Charles Jr., Jack, and Alan. All were born in Canada, except for Ab, who was born in Hong Kong during a family trip in 1927. The family returned in June 1928, minus sons Jim, Harry, and Frank, who stayed behind for a Chinese education and to keep their grandparents company.

Three months after returning, Charlie and Rose moved to Lucknow, Ontario — a town about two hundred kilometres west of Toronto, near the shores of Lake Huron — where they established Chin’s Restaurant. But the town’s nearly ninehundred residents of largely Scottish descent didn’t flock there for kung pao chicken or ginger beef — Chinese- Canadian food had not yet been invented. Instead, they came for sodas and fish and chips. Chin’s Restaurant soon became a favourite dining spot and helped the Chins blend in with the other families in town.

In an interview in July 2023, George told of how his parents spoke their native dialect of Sze Yup, but the children did not. They didn’t celebrate Chinese New Year, either. Charlie and Rose told their children that they were Canadian, not Chinese. When sons Jim, Harry, and Frank returned from China in 1938, they quickly learned English. Before long, they volunteered in the Canadian Army and the Royal Canadian Air Force, and saw action in Europe.

The Chin children were high academic achievers who were members of the school band, Girl Guides, Boy Scouts, and the Presbyterian youth group. Frank excelled at tennis, while most of his brothers played baseball in the summer and, of course, hockey in the winter — lots of hockey. The sisters did not miss out: Margaret played defence, while Mary played left wing on the town’s women’s hockey team, the Lilywhites. Gladys preferred Shakespeare over hockey.

All fourteen children worked at Chin’s Restaurant. Even friends would chip in and help. In an interview in May 2023, Henderson, now eighty-one, remembered helping Alan peel a one-hundred-pound sack of potatoes in the restaurant basement so they could hurry up and play shinny down there. It was Rose, he said, who gave him his first real hockey gear: a pair of gloves and shin pads.

Advertisement

The 1940s marked the beginning of organized minor hockey with the establishment of the Ontario Minor Hockey Association (OMHA) in 1935 and the Western Ontario Athletic Association (WOAA) in 1944. During the 1941-42 season, Ab and George, then thirteen and twelve, were on Lucknow’s bantam (under fourteen) team, and spearheaded the winning of the OMHA Bantam Championship. Bill, then fourteen, competed at the juvenile level (under eighteen). The following season, moving up to the juvenile level, Ab and George joined Bill to form the famous Chin line. That season, the brothers led the Lucknow Maple Leafs (the name of Lucknow’s juvenile team from 1943 to 1948) to capture the 1943 OMHA juvenile championship against nearby rival Wingham Indians.

Years of training together is what made this trio unbeatable. George recalled that Ab was the “muscle,” digging out the puck along the boards for his brothers. George’s secret weapon was his speed. Practising in the restaurant basement, he and Bill could pass the puck raised three to four inches off the ground. Bill was the sharpshooter, practising his aim on tin cans in upper and lower corners of the net. And they had mastered blind passing — exchanging the puck without looking at each other nor at the direction the puck was to go.

As a result, the boys were a powerhouse line, and it was not uncommon for them to score more than half of the goals in a single game. Lucknow’s arena, just half a block from the Chins’ family restaurant, was regularly packed to its 1,800-fan capacity. George recalled that farmers from as far as 130 kilometres away would come early to secure a spot, even hanging on the rafters to watch. After home games, autograph-seeking fans would line up outside Charlie’s eatery.

Perhaps due to their success in school and in sports, none of the Chins remembered being bullied or experiencing blatant racism. Bill, Ab, and George were idolized — to a point. The surviving siblings recall that parents in Lucknow forbade their daughters from dating any Chin boys, and George recounted how, on road games, opponents would yell, “Kill that C---k!” Charlie advised his sons to answer the insults by scoring more goals — which they did.

By March 1944, their astounding scoring record caught the attention of Carson Cooper, the chief scout for the Detroit Red Wings. Bill, Ab, and George accounted for one hundred of the 170 goals scored in eighteen games. Of the 425 points scored by their team that season, the Chins racked up more than half of them — a jaw-dropping 236 points. Despite the colour barrier in professional sports still being firmly in place, Cooper signed all three.

However, Clarence (Hap) Day, the coach of the Toronto Maple Leafs, surprised the Red Wings when he revealed that Bill had been signed by his team first, making the eldest of the trio property of the Leafs. Ab and George made it clear that wherever Bill went, they went. So the teens, then ages fifteen, sixteen, and seventeen, accepted spots at the Toronto Maple Leafs training camp in Owen Sound, Ontario. Pre-season testing began on October 10, 1944, and consisted of two hours of drills in the morning and two more in the afternoon, both followed by skating practice.

From October 23 to 25, thousands of fans turned out to watch the highly anticipated three-game Blue-and-White exhibition set to be played in Owen Sound, St. Catharines, and Toronto. Ted Kennedy, then a nineteen-year-old future Leafs captain, led the Blue team, while the Chin brothers played on the White team featuring veteran winger and two-time Stanley Cup winner Lorne Carr and future Hockey Hall of Famer, Sweeney Shriner.

During game one, George assisted on future Leaf defenceman Pete Backor’s goal in a 9-6 loss. In game two, Bill scored an unassisted power-play goal through the legs of Babe Pratt, the Leafs’ 1944 Hart Trophy winner and a veteran NHLer. As for Ab, he got a shiner in the 11-5 loss. The final game was played at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens before a crowd of 12,105 spectators. Although they played magnificently in an 8-2 loss, the Chin line didn’t score any points in game three.

Following this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, neither Bill nor Ab received a callback from the Leafs. George, under age sixteen, was ineligible. Reports that they would suit up somewhere as a unit in higher-level hockey at St. Michael’s College in the University of Toronto or playing for Port Colborne (about a thirty-minute drive from Niagara Falls) came up empty. Their demise may have stemmed from their small stature. In an era when the game of hockey meant hard hitting and fighting over finesse, agility, and speed, it isn’t difficult to understand why few envisioned NHL success for the Chin brothers.

Whatever the reason, hockey fans in Lucknow were not sorry to see their stars returning to play at home. During the 1944–45 season, George played on both the Lucknow midget and juvenile teams. It would be Bill’s last year playing juvenile, as he turned eighteen in 1945. Coach Pelt McCoy moved the whole team up to the junior level so that the three brothers could play together for the 1945–46 season.

McCoy’s winning combination did not claim the Ontario Hockey Association Junior C series championship that year. Leading up to the bestof- three finals, leg-weary Lucknow had played five games in ten days. After losing game one, Bill left the rink with a bad hip, a sprained thumb, and a gashed lip. Even then, in game two the Chin line thrilled the sellout home crowd, tallying all four goals in a 5-4 loss to the Goderich Flyers.

When the inaugural Windsor Spitfires Juniors held their tryouts in 1946, George made the cut, and the Chin line was broken up for that year. The brothers reunited for one final season as a line in 1947-48, leading the Lucknow team to win the 1948 WOAA Intermediate B series championship.

Between running his businesses and watching his sons’ games, Charlie had been in his glory, revelling in his boys’ stardom for ten years before having a fatal stroke in 1951 at age sixty. Rose, meanwhile, wanted her children to focus on their studies. Her message to them was: “You’re Chinese, so you need to get an education.” They listened.

In 1950, George entered the University of Michigan on a hockey scholarship, after winning the Turner Cup with the Chatham Senior Maroons. While no NHL offers ever came, as a phenomenal member of the university’s Michigan Wolverines hockey team George was named twice to the National Collegiate Athletics Association All-American team, leading the Wolverines to win back-to-back championships in 1952 and 1953. To further his studies in geological engineering, George went to England for his post-graduate studies and to play more hockey as a Nottingham Panther. Inducted into his alma mater’s hockey hall of fame in 1977, George was named in 2018 as the thirty-sixth best player in Michigan Wolverine ice-hockey history. George passed away in 2023.

Following in older brother Sam’s footsteps, Bill studied at the Ontario College of Pharmacy at the University of Toronto beginning in 1949. He graduated in 1953 and became a retail pharmacist. Later, Chuck would join them, co-owning Hallwyn Pharmacy in Toronto. Bill passed away in 1994.

Ab stayed in Lucknow to manage Chin’s Restaurant with his brother Morley. He coached his brother Jack’s bantam team to the 1952 OMHA D series championship. In their peewee (under twelve) 1952–53 season, Alan and his pal Paul Henderson were coached by Morley. Then, like George, Morley accepted a hockey scholarship in 1954 at the University of Michigan, where he earned a degree in geophysics. Ab coached Henderson after Morley’s departure. He eventually left Lucknow and joined a steamship company, becoming a wheelman. He died in 2007.

In 1955, along with her three youngest children, Rose moved to Toronto’s tony Rosedale neighbourhood. After twenty-nine years, she sold Chin’s Restaurant in 1957. Mary says her mother was most proud of producing ten university graduates: four educators, three pharmacists, two nurses, and one engineer. Rose passed away in 1990 at the age of eighty-five.

Hockey legend Henderson has never forgotten Rose and the Chin family’s kindness. Still in touch with his childhood friend Alan, he reflected, “If it wasn’t for a Chinese-Canadian family, I would never have scored the most important goal in Canadian history.” It’s a fitting tribute to an immigrant Chinese couple whose embrace of Canada’s favourite sport not only helped their family thrive but also contributed significantly to our national hockey legacy.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Starting at fifty dollars in 1885, then one hundred dollars in 1900, and finally five hundred dollars in 1904, the federal head tax proved ineffective in reducing the number of immigrants from China. In its place, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 was passed to put an end to further Chinese immigration. All persons of Chinese ethnicity — whether they were naturalized British subjects or Canadian-born — had to register with the government within twelve months of the law’s passage or risk fines, imprisonment, or deportation. They were given identity cards that stated in fine print: “This certificate does not establish legal status in Canada.” In 1947, the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, was finally repealed. That same year, the Canadian Citizenship Act granted all Canadians of Chinese descent Canadian citizenship.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement