We Need To Widen Our Views

I’m glad we are having this debate. I’m happy that Canadians are being jolted out of historical amnesia. As we argue about what versions of the past we want to tell, we are being forced to recognize that today has been shaped by yesterday.

But I’m not happy that these discussions are drenched in moral judgments about our forebears, without any acknowledgement that our predecessors lived in a world radically different from ours — different in ideologies, challenges, constraints, and goals. Individuals are being ripped out of context, and their characters trashed, with no attempt to understand the past on its own terms.

I’m not advocating that every single historical figure should be revered as legendary. But surely we can have a sense of proportion about whose achievements still merit respect and whose legacy is too toxic to swallow.

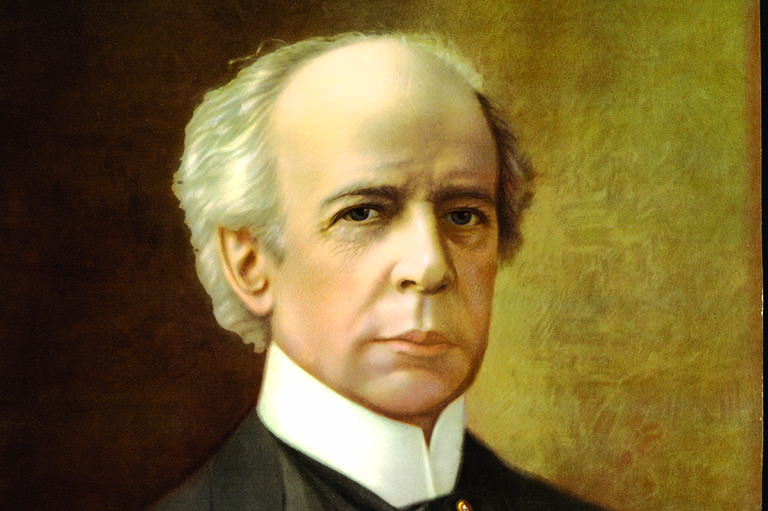

Let’s start with the recent shredding of Sir John A. Macdonald’s reputation. There are proposals that his name should be removed from Ontario public schools. The Canadian Historical Association’s prestigious Sir John A. Macdonald Prize has been rebranded as the CHA’s Best Scholarly Book in Canadian History prize. Last summer, one statue of Macdonald was removed from outside Victoria’s city hall while two more — one in Winnipeg, a second in Montreal — were defaced.

Macdonald’s offence was his role in the residential school system — a system that had been established before he became prime minister, that peaked about forty years after his death, and that continued under eighteen more prime ministers before the last school finally closed in 1996.

As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada reported, the system was a catastrophe for Indigenous peoples in Canada: Their children were horrifically abused, their cultures destroyed, their communities shattered.

Yet the issue, I would argue, is not who to blame but, rather, how did this happen? How can we understand the past, where people acted in ways that today we consider shocking? Instead of rushing to judgment in a triumphant display of wokeness, what about widening the perspective to see what was actually going on back then?

As I watched television clips from Victoria of Macdonald’s statue being carted away, I noticed a ridiculous irony. Fixed to the wall on the other side of the doors was the city’s coat of arms. It is laden with colonial symbols: Two blond angels represent colonization and civilization, with an all-seeing eye, the dove of peace, and a crusader helmet to represent Christianity.

As if the name of British Columbia’s capital and the Union Jack embedded in the provincial flag weren’t enough, this coat of arms hints that the British Empire lives on. The coat of arms reflects the beliefs with which Macdonald was raised — Britain was the motherland, Christian evangelism was used to justify oppression, and now-discredited theories of racial hierarchies held sway.

Sir John A. was a man of his time, but he was also a powerful leader. He moulded a handful of shabby British colonies into a new country and built a coast-to-coast railway to bind it together. He propelled the new Dominion towards autonomy. Without Macdonald, would there even have been a Canada?

The Fathers of Confederation developed a radical new idea on which to establish this country — a compromise between English-speaking and French-speaking settlers. In keeping with attitudes of the time, they failed to include First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in this bargain, and Canadians as well as Indigenous communities have been the poorer for that omission ever since.

Yet the idea of a nation based on political rather than ethnic links would, in the future, allow Canada to become the beacon of pluralism that our current prime minister loves to celebrate.

I can’t help wondering why our first prime minister had to be banished from Victoria’s city hall while the province continues to embrace peachy-cheeked angels and crusader armour.

The crucial role that the resourceful, risk-taking, pragmatic Macdonald played in shaping this country cannot be expunged from our history as briskly as his statue. Meanwhile, in a province with some of the largest non-settler, outdated symbols are still allowed to tell a story of white supremacy and racial bigotry.

Sir John A. Macdonald is far from the only national leader under attack these days. Statues and busts in public places explicitly celebrate their subjects. The debate about which historical figures should be toppled from their plinths is happening in several countries that are reframing their national narratives.

Sometimes the purges are easy to justify. Depictions of brutal dictators rarely survive the tyrants’ deaths; you won’t find monuments to Adolf Hitler anywhere in Germany, and Antonio de Oliveira Salazar is invisible in Portugal. There are apparently remote Russian fields crammed with banished statues of Stalin. (However, on a recent trip to St. Petersburg, I noticed a monumental statue of Lenin, who, despite unleashing violence and purges, has escaped obliteration because he overthrew Tsarist oppression.)

Equally easy to understand are the re-evaluations of the contributions made by some men who were eulogized for decades after their deaths, such as Cecil Rhodes in Britain and some leaders in the southern United States.

The most compelling argument to remove their statues is that the subjects’ whole careers were dedicated to upholding white supremacy, as imperialists (in the case of Rhodes) or defenders of the institution of slavery (in the case of Confederate heroes).

I am happy to see their lumps of masonry sent into exile. It is also instructive to see how, in some instances, history spoke to the present loudly and clearly. In Charlottesville, Virginia, the removal of an equestrian monument to Confederate leader and Civil War hero Robert E. Lee sparked an ugly outburst from alt-right protesters shouting racist slogans.

But other, more surprising figures have been caught up in these debates. Mohandas K. Gandhi seems an unlikely symbol of racial arrogance — Nelson Mandela once described the Indian leader as “the best hope for future race relations.”

Yet in 2016 the University of Ghana removed a statue of Gandhi from its campus after an online campaign (#Gandhimustfall) charged him with racism against black Africans. His extraordinary achievement in campaigning for the British departure from India with non-violent protest was not enough to save him.

At this point, I ask myself, can anybody survive scrutiny? Which historical figure is completely free of flaws? Some of the most celebrated heroes of progressive causes, among them Canadian suffragist Nellie McClung and British author George Bernard Shaw, endorsed eugenics. How do we balance our admiration for some of our predecessors’ ideas against our abhorrence of others among their beliefs?

I suggest that the only way is to widen the lens when reviewing historical figures. Don’t banish Sir John A. Macdonald in an Orwellian attempt to clean up the past. Instead, present him in all his complexity, as both a nineteenth-century patriarch and, to quote the title of Richard Gwyn’s biography, “the man who made us.”

Don’t eliminate him from view. Instead, amplify the information provided on the plaques and inscriptions that accompany his monuments. Yes, Macdonald was implicated in the cruel treatment of Indigenous peoples, and it is important to recognize that. But that’s only one aspect of a substantial legacy.

We need to be more tolerant of the moral failings of our predecessors — not as an act of charity to them but as an act of charity to ourselves. Our own unconscious assumptions and cultural habits are doubtless just as impregnated with biases as theirs were. The next generation is already berating mine for our wanton destruction of the environment, for our needless cruelty to factory-farmed animals, for our blind embrace of consumerism.

If we want the future to respect our moment in history, perhaps we should expand our knowledge of the past before we launch into spasms of outrage.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

The Trials of John A.

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!