From Protector to Hangman

October 6, 2018, the statue of John A. Macdonald in downtown Montreal’s Place du Canada square was once again vandalized, this time by “a group of anonymous local anti-colonial, anti-racist, anti-capitalist activists,” according to the Montreal Gazette. The statue had been drenched in paint earlier that year, and it was beheaded in 1992, in all likelihood to protest the failure of the Charlottetown Accord.

Despite the Quebec backdrop, it would appear that the latest incident was not related to Macdonald’s treatment of either French Canadians or Quebecers but, rather, was motivated by his actions against Canada’s Indigenous peoples, who remain animated by a painful history tainted by Macdonald’s legacy.

To francophones, on the other hand, he is a mostly forgotten or indifferent figure. In Canada’s early days, however, French Canadians regarded him rather highly.

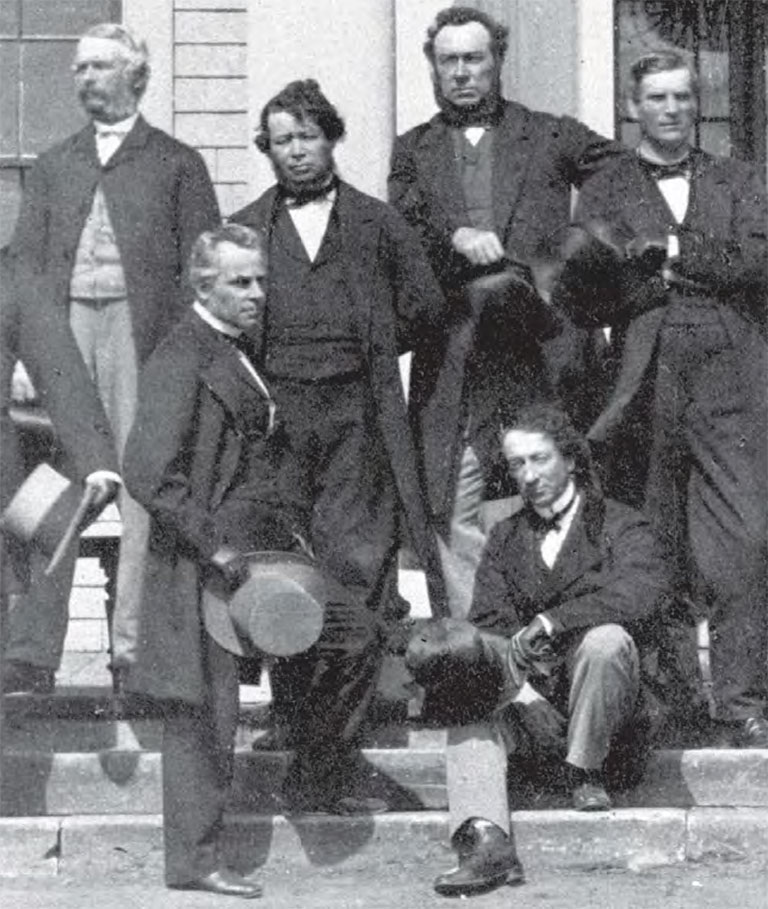

Relations between French Canadians and John A. Macdonald were indeed rather positive during the first twenty years of a nascent Canada. His Conservatives found more allies than opponents among francophones, especially within the Roman Catholic Church, which had supported Confederation in 1867.

At the time, many French-Canadian Catholics were alarmed by radical liberals — “Les Rouges,” spearheaded by brothers Antoine-Aimé and Éric Dorion — who were considered by many to be extremist opponents of the church.

By contrast, for French-Canadian Catholics, Confederation as championed by John A. Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier seemed the best protection against annexation to the American republic.

In this context, Macdonald may not have been hailed altogether as a saviour, but, to be sure, he was seen as a much lesser evil than the prospect of being dissolved into American culture.

In the 1960 National Film Board documentary Le chanoine Lionel Groulx, historien, the nationalist historian Lionel Groulx recounted a story from his childhood. When mock elections were staged by the pupils in his primary school, he played the role of Macdonald.

He recalls proudly saying these lines as a schoolboy: “We are the sons of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We shall not back down before the sons of Dorion and George Brown.” The young Groulx, it would seem, represented quite accurately the character of the Tory leader as imagined by French-Canadian Catholics.

Nevertheless, it is around this same time that relations between Macdonald’s Conservatives and French Canadians started to sour somewhat, as the latter began to doubt Macdonald’s commitment to French rights.

Starting in 1871, according to Susan Mann Trofimenkoff in her 1986 book Visions nationales: Une histoire du Québec, the province’s ultramontanists — those who saw the church as supreme over the rest of society — pressed Macdonald’s government to protect Acadian rights in New Brunswick by disallowing a provincial law intended to stop funding Catholic schools in the province.

Despite pressure from a number of prominent Quebec legislators, Macdonald refused to disallow the law, fearing even greater opposition from his own party’s Orangemen, anti-Catholic conservatives originating in sectarian Ireland. To this end, Macdonald argued that Confederation was founded upon the recognition of cultural and national distinctions among provinces as well as the principle of provincial autonomy, a position he had held even before 1867.

Indeed, on February 6, 1865, Macdonald had said in an address to the House of Assembly that the “people of Lower Canada” sought to protect the province’s cultural “individuality.” This fact made a legislative union between provincial entities impossible, which was an outcome Macdonald likely favoured personally.

He used the same argument — the obligation to respect the will of Lower Canada — when the issue of New Brunswick schools was debated in the House of Commons on May 14, 1873. “Lower Canada contained a different race and used a different language.

The majority had a religion which was in the minority in the whole Dominion, and they claimed and justly claimed as a protection to them ... that we should not have Legislative Union….” Paradoxically, then, respecting Lower Canada’s provincial jurisdiction prevented Macdonald from supporting French Canadians elsewhere in the country.

In fairness to Macdonald, he was in a difficult position. On one side, French Canadians outside Quebec demanded that the federal government use its power of disallowance to revoke provincial laws that limited their rights, as it had seen fit to do under different circumstances.

On the other side, Macdonald faced considerable resistance from the provinces, especially Ontario, that forcefully defended their own jurisdiction against any manner of federal centralism. Indeed, this was a time when power relations between the central government and its federated entities were in a process of redefinition, a process that favoured increased provincial authority.

In this context, it would have been difficult for Macdonald and the Conservatives — had they been so inclined — to fully and completely defend French Canadians outside Quebec, lest the federal government be charged with an illegitimate intrusion into provincial affairs. Thus, while Quebec obtained some acknowledgement of its distinction, this was done, as historian Jean-Charles Bonenfant has written, “with little regard for the fate of French minorities in other provinces.”

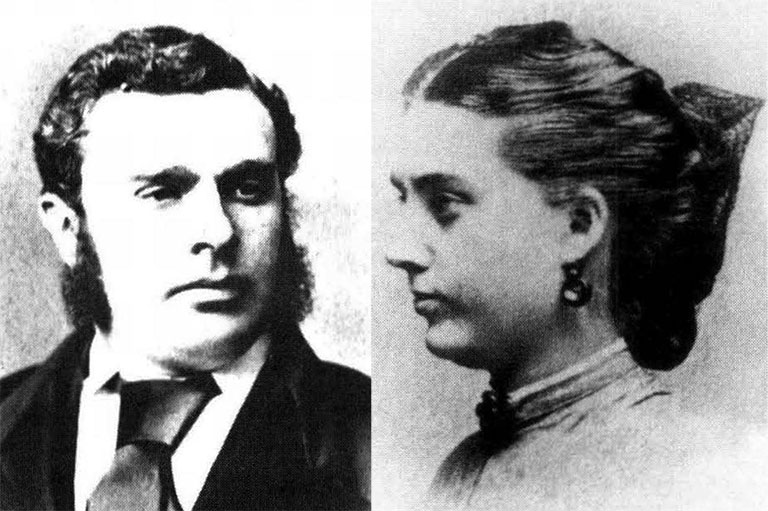

Nevertheless, Macdonald held French Canada in relatively high regard, which might have been due to the Quebec contingent of his entourage. Indeed, he surrounded himself with effective and talented French-Canadian colleagues, starting with Cartier. Their number also included Étienne Parent, a highly regarded intellectual who would become undersecretary of state and who had, according to historian Patrice Dutil, a profound influence on Macdonald’s perceptions of Quebec, as well as Robert Bouchette, the deputy minister of customs.

Whatever goodwill might have existed, however, would collapse irremediably in the wake of the execution of Métis leader Louis Riel. Now considered a Father of Confederation, after the Northwest Resistance of 1885 Riel was branded a traitor by the Macdonald government and sentenced to hang. Relations between Macdonald and French Canadians, until then positive if not quite cordial, deteriorated to the point of no return.

In choosing not to grant Riel amnesty, Macdonald and the Conservatives certainly knew they would precipitate a storm, but they wagered that it would be sudden and brief. The other option, sparing Riel, would have triggered a veritable hurricane in Ontario.

Helping to tip the balance against Riel was the fact that, until that time, French Canadians had shown little regard for the Métis. This led Macdonald to believe that his image might emerge somewhat tarnished from the episode but not completely destroyed.

To the contrary, French Canadians found in Riel’s hanging proof that one of theirs was killed by an Anglo-Saxon government resolutely against francophones. The leader of Quebec’s Parti national, Honoré Mercier, seized upon this issue in his party’s successful effort to dislodge the provincial Conservatives. After the Riel affair, John A. Macdonald and the Conservatives had become “the party of the noose” in the eyes of French-Canadian Catholics.

It would take considerable effort for the Tories to regain the favour of the Quebec electorate.

This perhaps explains why, when the time came to celebrate Canada’s 150th anniversary in 2017, Macdonald’s role did not figure prominently in Quebec.

Certain commentators have noted that Hector-Louis Langevin, a francophone, unjustly carries the blame for the actions of his leader, who was the person truly responsible for residential schools. (In June 2017 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau cited the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada as he stripped Langevin’s name from the Ottawa building housing the Prime Minister’s Office and the Privy Council Office.)

Macdonald is remembered as a somewhat dark figure. But he is someone, because of the role he played in the foundation of Canada, whose monuments should remain standing.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

The Trials of John A.

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!