Soberly Celebrating Sir John

This wasn’t the first time King had written about a mystic vision in his diary. And it wasn’t his first reference to Canada’s founding prime minister. But the vision was remarkable in that it gave birth to what was then an unconventional idea — to hold a major commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of Macdonald’s death, on June 6, 1941. The idea was unusual for at least two reasons: It was being initiated by a Liberal prime minister (Macdonald was a Conservative), and there was no consensus about whether Macdonald deserved the recognition.

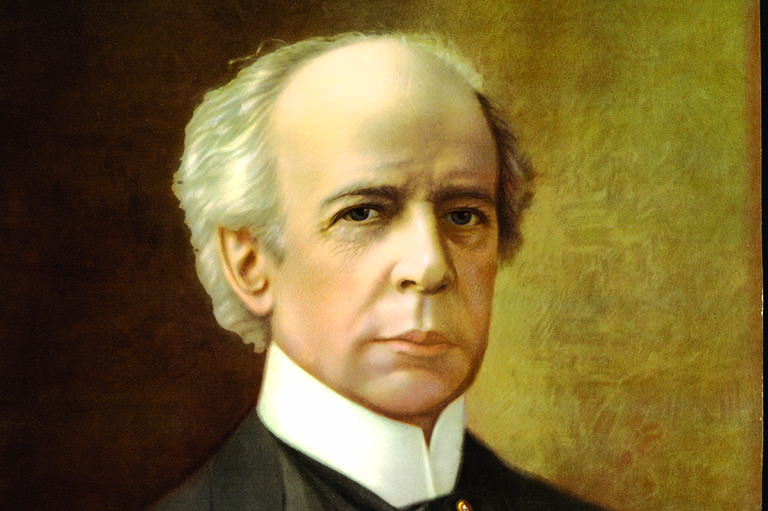

Born on January 11, 1815, Macdonald spent more than fifty years in Canadian politics and he was certainly an irrefutable historic figure. He masterminded the union of British North America and was the lead drafter of a Canadian constitution that sought conciliation between French and English Canadians. He was Canada’s first prime minister, a role he occupied for nineteen years, and he steadfastly championed a national railway to unite the new country But his star faded with some Canadians when they became aware of his penchant for drinking, his use of gerrymandering, and his knowledge of bribes. His insistence on hanging Metis leader Louis Riel, “though every dog in Quebec bark in his favour,” did not win him friends in French Canada, and his policies towards Aboriginal Canadians and Chinese migrant workers are today perceived as racist.

Macdonald often came under partisan attack while he was alive, and attacks on his legacy continued after his death in 1891. When Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberals came to power in 1896, they allowed his memory to fade from the public’s consciousness. Even King went out of his way to shift the focus away from Macdonald to a broader focus on other relatively unknown Fathers of Confederation during the Diamond Jubilee Celebrations of Confederation in 1927.

So why did King suddenly want Macdonald commemorated in 1941? The answer is that King needed a reason to bring the nation together. Canada was increasingly being called upon to assist its wartime allies — and the country was by no means united about the sacrifices that had to be made.

The spring of 1941 was a difficult time. Canada had declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939, and Parliament had passed the National Resources Mobilization Act in June 1940, giving government special emergency powers to mobilize all human and material resources for the defence of Canada. Canadian troops were being sent overseas, and recruitment intensified as more men were needed at the front. Pressure was building to introduce conscription — an issue that had pitched the country into a crisis during the First World War. King was intent on avoiding a repeat. Yet the promise to avoid conscription for overseas military service would be difficult to keep.

Two weeks after having his mystical vision of Macdonald, King announced to the House of Commons his government’s intention to organize a “suitable ceremony” in Kingston, Ontario, where Macdonald was buried. With less than three weeks before the event, the planning had to be carried out expediently. King chaired the organizing committee and named most of its members, with the exception of a few local Conservative members from Kingston, who were added by acting Conservative Party leader Richard Hanson. They agreed to four speakers: Hanson and King as national party leaders; Sir Arthur Meighen as the only other living Canadian prime minister; and King’s Quebec lieutenant, Ernest Lapointe. They also secured the live broadcasting of the event by Canada’s radio stations, then still a rare technological feat. As a live radio event in the pre-television era, it would give King an opportunity to reach inside the homes and workplaces of Canadians.

Hoping to ensure a large crowd, King held the event on a Saturday — one day after the actual anniversary of Macdonald’s death. While travelling on the train from Ottawa to Kingston that morning, King made some last-minute revisions to his speech. “I think I got it into nearly perfect shape at last,” King wrote in his diary that day. “It came to express exactly what I wanted: first, of unity in historic races, and then of unity in the nations of the Commonwealth, and unity in fighting for the preservation of peace.”

King placed a wreath at the base of the statue and then spoke for ten minutes.

“I leave to others to speak of Sir John Macdonald’s career and attainment,” he began, thus allowing more time to focus on his key theme. King then stated what he viewed as Macdonald’s hope for unity: “A country of two races merged into one I nationality, governed in the well-tried ways of the British constitution, a pride and glory to the new world, this was the daydream of his youth. Its unity was the hope and the prayer of his riper years. Sir John not only lived to see his dream realized and his prayer answered, but both, in memorable part, affected by his own exertions.”

King defined the entirety of Macdonald’s political career as one dedicated to national unity. By doing so, he purposefully ignored many chapters of Canadian history where Macdonald’s policies and decisions — the hanging of Riel, for example — created national disunity. His selective memory allowed him to note that Macdonald had achieved the ultimate goal: from the “union of two historic races” emerged “one young and vigorous nation.”

All of the speakers that day cast away any real or perceived criticism of Macdonald’s legacy.

The other speakers followed closely King’s portrayal of Macdonald. In his speech, Hanson, the Opposition Conservative Party leader, pleaded with Canadians “who inherited the early fruits of [Macdonald’s] work [to] strive to make of this nation the best that is possible for all of our people. In diversity there can be true unity.”

Lapointe, the leading political figure from Quebec and the only French-language speaker, spoke to French and English Canadians in their respective languages. “[A] dark cloud hangs over our civilization,” he said. For Quebecers listening to the broadcast, Lapointe asserted that Macdonald had been responsible for safeguarding the French language in Canada. Speaking in French, he said, “Thank you, Sir John! We salute you as one of the first champions of national unity. French Canadians are delighted to join their fellow Canadians to pay tribute to your memory”

The remaining speaker, former Prime Minister Arthur Meighen, a Conservative, focused on elevating Macdonald’s status beyond that of a Conservative Party icon and into a national symbol. He noted that Laurier had awarded Macdonald “the primacy among the founders and the builders of our nation.”

In short, all of the speakers that day cast away any real or perceived criticism of Macdonald’s political legacy or personal story to ensure that Canadians could rally around this new image of Sir John A. Macdonald as a unifying force.

“I thought all the speeches good,” King wrote later in his diary. “Meighan’s very good, but with blemishes; very poorly delivered. Lapointe the best of all. Hanson better than usual.” After the speeches, King reviewed the troops and then mixed with the crowd. “I was agreeably surprised and pleased by the reception I got from the people on the streets after the review,” he noted. The ceremony finished with the dignitaries going to the cemetery to place wreaths at Macdonald’s grave.

The considerable coverage in Canada’s newspapers the next day was overwhelmingly positive. The Toronto Star focused on Macdonald’s role in conciliating English and French Canadians as the chief success of his political career. The Globe and Mail noted Macdonald’s ability to “put national welfare ahead of party.” Montreal’s French-language paper, La Presse, ran the headline, “L’unite natio-nale jut I’espoir et le voeu de sir John-A. Macdonald” (National unity was Sir John A. Macdonald’s hope and wish).

The newspapers also carried interesting editorial reflections. A La Presse editorial noted that Canadians should be inspired by the examples offered by French and English Canada’s Fathers of Confederation. “The political formula they adopted remains the correct one,” said La Presse in French. “By following that formula, we serve the best interests of the Dominion and the vital causes that we are committed to defend.” The Montreal Gazette’s editorial referred to the “transcending power of Sir John Macdonald’s example” and hoped that current leaders would copy his model.

A series of articles in the Kingston Whig-Standard suggested that the commemoration had already made an immediate impact on French-English relations in Canada. A day earlier, Thomas Ashmore Kidd, a grand knight of the Orange Order and a former Ontario MPP for Kingston, had told a gathering in Kingston, “Canada’s war effort is not Imperialistic enough, ... the official war effort goes only so far as a certain element in the Province of Quebec ... and French-Canadians were probably disloyal, given their poor showing in the enlistment figures for the war.”

The editors of the Whig-Standard were quick to rebuke Kidd’s stance: “To talk about Quebec Province as if it were trying to hinder Canada’s war work is manifestly unfair. We do not know what military quotas are given to the various provinces, but we do know that Quebec has maintained the quota of reinforcements allotted to it as well as any province in Canada.”

The spirit of the editorial rebuke emerging from Kingston, a community with a long association with the Protestant Orange Order, reflected the tone set at the national commemorative event. For the first time since his death in 1891, Macdonald was a universally acclaimed national figure, heralded by senior members of both the Liberal and Conservatives parties. The media accepted this without criticism or further analysis.

However, this positive attitude was not to last. In the months and years following the event, the political debate on overseas military service would again divide the country, as it did during the First World War. The memory of Macdonald as a unifying force was not enough to heal the ongoing deep divisions between Quebec and the rest of Canada.

After the war, subsequent prime ministers — even Macdonald’s self-proclaimed greatest admirer, John Diefenbaker — have treaded carefully in commemorating Macdonald. The emergence of a voice for greater independence for Quebec during the 1960s made many federal politicians uncertain about commemorating the primary Father of Confederation. Pearson repeatedly dithered on commemorating Macdonald as part of Canada’s centennial celebrations in 1967.

The January 11, 2015, bicentennial of Macdonald’s birth was marked by modest celebrations. The Kingston-based Sir John A. Macdonald Bicentennial Commission and Historica Canada received $500,000 and $360,000, respectively, in federal funding to promote Macdonald’s memory. In addition, Canada Post released a commemorative stamp, and the Royal Canadian Mint released a number of commemorative coins.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement