The Architect & the Lady

-

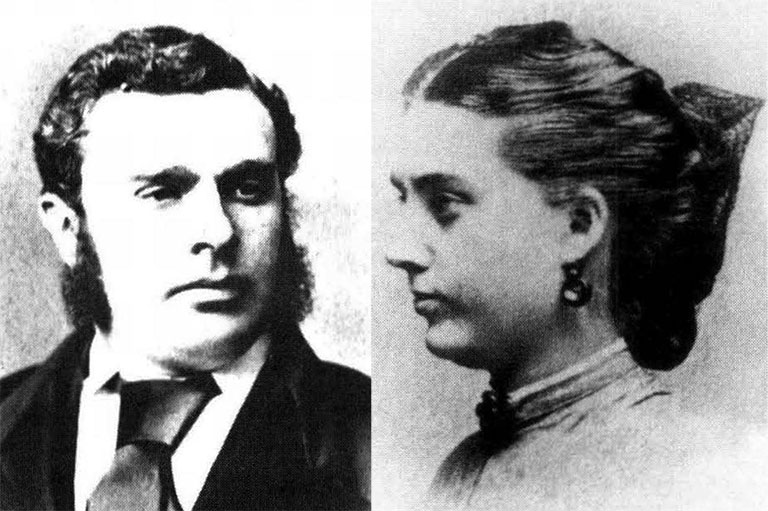

Rattenbury was fifty-six when he met Alma Pakenham in 1923. He had had a decade of career reverses and his marriage had turned sour. She seemed to him like a new lease on life. Coincidentally, his architectural career had begun to revive.B.C. Archives / F-02163

Rattenbury was fifty-six when he met Alma Pakenham in 1923. He had had a decade of career reverses and his marriage had turned sour. She seemed to him like a new lease on life. Coincidentally, his architectural career had begun to revive.B.C. Archives / F-02163 -

Though only in her midtwenties when she met Rattenbury, Alma Pakenham had had a full life. She had buried one husband and divorced another, and was the mother of an infant son. A musician, she resumed a concert and songwriting career after the war.Courtesy John Rattenbury

Though only in her midtwenties when she met Rattenbury, Alma Pakenham had had a full life. She had buried one husband and divorced another, and was the mother of an infant son. A musician, she resumed a concert and songwriting career after the war.Courtesy John Rattenbury -

For ambitious young man-about-town Francis Rattenbury, Florence Eleanor Nunn seemed an unlikely choice of bride. She was rather plain and retiring and her family was neither wealthy nor well-connected, but she had a sweet nature.They married in 1898 but before their two children had reached their teens, antipathy had grown between them. Florrie, as she was called, did not share her husband’s interest in moving in Victoria society; he found her dull.BC. Archives / B-07986

For ambitious young man-about-town Francis Rattenbury, Florence Eleanor Nunn seemed an unlikely choice of bride. She was rather plain and retiring and her family was neither wealthy nor well-connected, but she had a sweet nature.They married in 1898 but before their two children had reached their teens, antipathy had grown between them. Florrie, as she was called, did not share her husband’s interest in moving in Victoria society; he found her dull.BC. Archives / B-07986 -

Alma Clarke was a bright and vivacious child, with a prodigious musical talent. After an early performing career, she married Vancouver realtor Caledon Dolling. She joined the French Red Cross after he died at the battle of the Somme in 1916. She was wounded and received a Croix de Guerre from the French government for her services.Courtesy John Rattenbury

Alma Clarke was a bright and vivacious child, with a prodigious musical talent. After an early performing career, she married Vancouver realtor Caledon Dolling. She joined the French Red Cross after he died at the battle of the Somme in 1916. She was wounded and received a Croix de Guerre from the French government for her services.Courtesy John Rattenbury -

Francis Mawson Rattenbury was only twenty-five when he won the 1893 competition to design nothing less than the legislative buildings for the province of British Columbia.Terry Reksten

Francis Mawson Rattenbury was only twenty-five when he won the 1893 competition to design nothing less than the legislative buildings for the province of British Columbia.Terry Reksten -

Rattenbury’s design for the B.C. Legislature, a pastiche of Romanesque and Italianate style with a nod to neo-Gothic, was chosen from sixty-seven entries. The public was galvanized by its grandeur when it opened in 1898. Though later the architect would be dogged by talk of design flaws, he would go on to become British Columbia’s most sought-after architect, designing most of the province’s major buildings.BC. Archives / I-26336

Rattenbury’s design for the B.C. Legislature, a pastiche of Romanesque and Italianate style with a nod to neo-Gothic, was chosen from sixty-seven entries. The public was galvanized by its grandeur when it opened in 1898. Though later the architect would be dogged by talk of design flaws, he would go on to become British Columbia’s most sought-after architect, designing most of the province’s major buildings.BC. Archives / I-26336 -

The chateau style was the signature of CPR hotels at the turn of the century, which Rattenbury accommodated in his design for Victoria’s Empress Hotel. By 1906, frustrated at demands for last-minute changes to his plans, he resigned from the project and severed his connections with the CPR.BC. Archives / B-04740

The chateau style was the signature of CPR hotels at the turn of the century, which Rattenbury accommodated in his design for Victoria’s Empress Hotel. By 1906, frustrated at demands for last-minute changes to his plans, he resigned from the project and severed his connections with the CPR.BC. Archives / B-04740

Francis Mawson Rattenbury’s mother dreamed that one day her son would make his living in the Mawson family wool business, but the Rattenbury men had always been unpredictable in their choice of careers. The family tree included both clergymen and pirates, and Francis’s father had earlier rejected his wife’s family’s business in favour of a more fulfilling life as an artist. One thing was certain, though—whatever path a Rattenbury man chose, he followed it with consuming passion.

Like his father, Francis, born at Leeds, England in 1867, rejected the wool business, choosing instead to join his mother’s bachelor brothers in their architectural firm as an articling student. He learned his lessons well, and by the time he was twenty-five decided to strike out on his own. British Columbia seemed the perfect place for an ambitious young architect in those days. In 1887 Vancouver had been established as the terminus of the transcontinental railroad, and in just a few years had grown from a disreputable little shantytown into a bustling city of fifteen thousand.

But when Rattenbury arrived in Vancouver in 1892, the province was on the brink of a recession and virtually no building was taking place. Since opportunities were few for a relatively inexperienced architect, he let it he known that he’d been associated with the prominent British architect, Henry Francis Lockwood, who had been a business partner with his uncles. But Lockwood had died when Francis was only eleven years old, and they’d never met. With the help of this small deception, Rattenbury procured at least one commission to design a house during those first lean months.

It was a magical time of life for Rattenbury, when absolutely anything seemed possible. So when a competition to design the new British Columbia legislative buildings in Victoria was announced, he was undeterred by feelings of inadequacy. At least a few of the young unknown’s competitors must have been surprised when his design was chosen from sixty-seven entries. It was an unbelievable stroke of good fortune and it taught Rattenbury a memorable lesson: trust in Lady Luck. Even though the capricious lady would often disappoint him, his belief in her good will never wavered, and she came to influence every major decision he ever made.

His fame as the designer of the new legislature brought him a great deal of additional work—courthouses in Chilliwack and Nanaimo, mansions in Vancouver—but he also found time for recreation, for boating, swimming, long walks, even afternoons lying in a hammock. He wrote his uncle, Richard Mawson: “I could never imagine a country with so many inducements as this has for lotus-eating, and I think it just as wise to enjoy life whilst I have the opportunity and desire, especially as I have been as fortunate as my most sanguine expectations.”

His letter mentioned no female companions, but Rattenbury was probably already involved with his future wife, Florrie. Florence Eleanor Nunn has been described as physically unattractive and lacking in social skills. Francis was both handsome and charming, probably the most eligible bachelor in Victoria. But Florence was very sweet-natured, and somehow she appealed to him. They began keeping company.

When the grand opening of the legislative buildings was celebrated in February, 1898, Rattenbury was too busy to attend. The Klondike gold rush was at its peak and he could see opportunities everywhere. With three prefabricated steamboats built at the Albion Iron Works in Victoria, he expected to make a fortune transporting miners and supplies down the Yukon River. For good luck, he’d christened the three boats, Ora, Flora, and Nora, after Florrie, who was pregnant.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Rattenbury had developed into a somewhat flamboyant public figure by this time, but, in view of Florrie’s condition, a quiet summer wedding seemed best. The honeymoon, by contrast, was a hike across the daunting and arduous Chilkoot Pass, on the B.C-Alaska border, a crossing that had staggered and even killed Klondike-bound prospectors. However, Rattenbury, who had a vested interest in the gold strike, chose to minimize the terrible difficulties, later complaining in a letter to the Victoria Colonist “how ridiculous and exaggerated” other accounts of the pass had been.

That summer Rattenbury was paid forty thousand dollars to transport sixty head of cattle to Dawson City, almost as much money as he’d realized from the legislative buildings project. But after this fortuitous beginning, Lady Luck turned her back. Within a year Alaska was the new focus of gold fever. The Klondike rush was finished; the transportation business was finished; and the Ora, Flora, and Nora were broken up and converted to barges.

Rattenbury returned to architecture, a field where he could excel in spite of ever-increasing competition. “In Victoria,” he wrote to his uncle, “there are many architects … They come here and love the place so much that they prefer to stay, even on the smallest inducement. I luckily got three good clients, the Government, the C.P.R. and the Bank of Montreal.”

For the next fifteen years he left his mark wherever the government, the railroad, and the bank did business. They were productive years. “Ratz,” as he came to be known, was consistently able to get prestigious work. Nevertheless he yearned for a project as important as the legislative buildings. Rumours that he’d copied the design from a maharajah’s palace in India constantly irritated him. And there were flaws he found difficult to accept, notably poor acoustics (resolved by hanging salmon fishing nets from the ceiling on a framework of steel wires) and insufficient toilets (unresolved). He wanted to design something so monumental that it would overshadow the flaws of his first major project. Then in 1902, he was approached by Charles Melville Hays, general manager of the Grand Trunk Railway, who planned to build Canada’s second transcontinental rail line. Hays wanted Ratz to design the coast city of Prince Rupert as well as every hotel and building on the line. It was exactly what he’d been looking for.

In the meantime, the CPR had awarded him the commission for the Empress Hotel on Victoria’s inner harbour, adjacent to the legislature. “It is going to be a whopper,” Francis wrote to his mother. But by 1906, annoyed by last-minute demands for changes in the locations of the lounge and dining room, Rattenbury impulsively resigned from the Empress Hotel project and severed his connections with the CPR, gambling that the GTR project would prove to be the more lucrative. His Klondike adventure years earlier had nearly bankrupted him, but this decision would prove more ruinous.

In 1912, Hays, who had been raising funds in England for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, a subsidiary of the GTR, decided to return home on the Titanic. He and the signed agreements he carried with him went down with the ship. He was soon replaced, but the project lost much of its momentum. The first train finally rolled into Prince Rupert in April 1914, with regular service scheduled for September, but in August, Britain declared war on Germany and all architectural work was halted. By 1918, the GTR was bankrupt.

The railway’s collapse was a double disaster for Rattenbury. Several years before the railroad had ever publicly announced its new route, Ratz had committed almost his entire fortune to purchase 4,500 hectares of land along the future right-of-way. He’d gambled both his career and his savings on the GTR and lost. Lady Luck seemed to have deserted him.

During the war Rattenbury occupied himself a few hours a day with designing an addition to the legislative buildings, but the rest of the time he socialized at the Victoria Union Club or stayed in his bedroom drinking and brooding. His marriage, like the rest of his life, was a disappointment. He’d given Florrie everything, but she showed no interest in being stylish or socially attractive. He’d changed and grown; she’d remained the simple soul who’d been his companion on those magical afternoons so long ago.

After 1918, when building started up again, Rattenbury found himself unable to compete. Projects that would once have been his automatically now went to others. He’d lost his fortune, his career was in tatters, and he was unhappy in his marriage. The pattern of drinking and brooding continued, and it seemed for a while that his life was over.

Then the Victoria Chamber of Commerce asked Rattenbury to submit plans for a swimming pool. Sensing an opportunity, he designed an immense entertainment center, including shops, ballrooms, tropical gardens, picture galleries, and three heated saltwater pools. The entire complex covered more than nine thousand square metres and was enclosed by a single roof of glass and steel.

If tax exemptions the city had previously granted the CPR on the Empress Hotel hadn’t expired, it’s unlikely such a grandiose scheme would have been considered. But when railroad management heard of Rattenbury’s proposal, they offered to fund the project in return for continued exemptions on the hotel. Interest in the complex reached a fever pitch, and on December 19, 1923, a city-wide referendum was held on the question of building the Crystal Gardens in return for tax exemptions. It passed with a majority of 2,909 to 352.

That evening Ratz was the guest of honour at a celebration in the Empress Hotel dining room. Afterwards, intoxicated with success and a few drinks, he drifted into the lounge and came face-to-face with the talented and glamorous Alma Pakenham, the very embodiment of Lady Luck. This meeting would change his life irrevocably.

She was, wrote one chronicler, “beautiful, with a lovely oval face, deep hauntingly sad eyes and full lips which easily settled into a pout, at once fashionable and sensuous. Her voice had a warm vibrant quality, pitched very low, musically slow and distinct.” Rattenbury, disappointed and unhappy for so long, was smitten.

No official record of Alma’s birth has ever been found, but she was probably born during Rattenbury’s early years in Victoria. When she met fifty-six-year-old Rattenbury, she was in her mid-twenties. She’d also been married twice, widowed and divorced, and was the mother of an infant son.

Alma had always been expected to accomplish great things. She was described by a teacher at St. Ann’s School as “brilliantly clever … a vivid little thing full of happiness and music, with a special attraction of her own.” She had an unusual musical talent, and while still in her teens performed on piano and violin with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra.

She first married in 1913, but her husband, Caledon Dolling, was killed at the battle of the Somme in 1916. Alma joined the French Red Cross after his death, and served as an ambulance driver. She was wounded twice, and decorated by the French government.

After the war, she became involved with a married man, Thomas Pakenham, and was named in a divorce suit for the first time. They married in early 1921, and their son was born that summer. But the relationship soon broke down, and Alma returned with her son to her mother’s home in Vancouver. She revived her musical career and began to give concerts in Vancouver and Victoria. So it was that she happened to be in the lounge of the Empress Hotel after Rattenbury’s victory dinner.

“I had been playing in Victoria,” she wrote to a friend, “and on returning to the hotel I sat yarning for a while with K. in the lounge. From the banqueting hall came the sounds of revelry and singing.… K. suggested that we should try to get a peep into the room, which we did, and to K.’s amazement he found that the honoured guest … was an acquaintance. Soon after … some of the men strolled in to finish cigars and pipes. K. introduced me to his acquaintance, and so it was that I first met my Ratz.”

She knew Francis was thirty years older, but found him irresistible. She accompanied him to a dance soon afterwards. Later, in a letter to a friend, Rattenbury described their whispered exchange as they glided around the floor together. She said, he wrote: “‘You know, you really do have a lovely face.’

‘Great Scot,’ said I. ‘Have I? I’m going right home to have a look at it. I never thought it worth looking at before.’

I’m not joking,’ she said. ‘You really have almost the kindest face I ever saw.’”

Alma moved to Victoria, and leased a small house on Niagara Street where Francis became a frequent visitor. There was little need for discretion, or so Rattenbury thought. Florrie had never been accepted by Victoria society, and everyone, he felt, was bound to support him now that he’d found someone so much more suitable. But there were doubts. One of his longtime friends thought Francis had been bewitched. Then there was gossip about drugs. It was known that many young women who’d served with medical units during the war had developed a drug dependency. Alma smoked constantly, and always consumed several drinks more than she should. It was easy to believe she was a drug addict, and equally easy to believe that Francis’s sudden rash behaviour was the result of drug use.

He was prepared to sacrifice anything for Alma, but assumed he’d only be required to give up his wife who he was tired of anyway. When Florrie refused to divorce him, he moved out and disconnected the light and heat. After this tactic failed, he began entertaining Alma in the living room, driving Florrie upstairs. By 1925, discouraged and brokenhearted, she’d lost the will to fight, and, for the second time, Alma was named in a divorce suit.

Soon after Francis and Alma were married, they had a son. They were intensely happy together, but those Francis had counted on had turned hostile. After Florrie’s death in 1929, he found himself publicly shunned and avoided on the streets. His relationship with Alma had estranged him from everyone he’d ever cared for, including his two grown children. The couple discussed it between themselves and realized it would be best to leave. The only one who came to see them off at the dock on the day of their departure for England was his son, Frank. Speaking of it later in the Vancouver Sun, Frank commented that Alma “was in a stupor from booze or something else.”

On the first leg of the voyage Francis was drawn into a card game with people he assumed to be fellow tourists. By the time they arrived in New York he was deeply in debt, and realized that he’d been taken in by professional gamblers. He decided not to pay, and late that night they fled the city, first taking a late night train to Montreal, then boarding a ship for Europe.

It was six months after leaving Victoria that the Rattenburys settled into a rented house in Bournemouth, a pleasant city on the south coast of England. They lived comfortably, with two servants to look after them, but, with no income, Francis was obsessed with money. His wife soothed his anxiety, reminding him of her musical talent and the royalties that would pour in once she had reestablished her reputation.

At first he supported her efforts. A few of Alma’s songs were published as sheet music, but the income was disappointingly small, and he soon lost interest. Alma was left to pursue her career alone while Rattenbury sank further and further into depression. Always somewhat of a flirt, and with her husband grown indifferent to sex, she began showing interest in other men. But she didn’t take a lover until seventeen-year-old George Stoner applied for the job of family chauffeur and handyman in September, 1934. Later, in court, Stoner’s uncle would describe him as “a good, honest boy, and the best boy that I have ever seen in my life,” adding that he’d never known his nephew to have anything to do with girls. Alma, finding the youth’s pleasant features not disagreeable, and perhaps sensing his pliable nature and lack of sophistication, hired him. Within two months, he was her lover. Installing him in the house in a spare bedroom, she believed she was taking no risks. Francis, she later claimed in court, had told her to lead her own life, and she was doing so.

Alma believed herself in love with Stoner. And Stoner, for his part, fell in love with Alma. He had been transformed virtually overnight from an innocent youth to the lover of a beautiful older woman who’d already had three husbands. Perhaps he hoped to be the fourth. He was jealous of any attention Alma paid to Ratz, and became impassioned when she suggested their affair might have to end. In March, Stoner chauffeured Alma to London for a lover’s holiday. But it was a dream that could not be sustained. After three days of dining, shopping, and theatregoing, they returned to Bournemouth to find Ratz morbid and talking of suicide. Alma comforted him. But the insecure Stoner misinterpreted her gestures and became enraged.

After placating her lover, Alma assumed everything was back to normal, but around midnight on March 25, 1935, soon after Stoner had joined her in bed, Alma heard someone groaning on the main floor. She went downstairs to find Francis unconscious in his chair, his hair matted with blood. When the doctor arrived, she said Francis must have fallen and hit his head on the piano. By the time the police arrived, she’d had more time to think about what must have happened and told them Francis had tried to kill himself with a wooden mallet. She revised her story again, first saying she’d hit Francis with the mallet, then that Stoner had done it. Left alone after Ratz was taken to a nearby nursing home, Alma, braced by a few stiff drinks, offered an attending policeman money, then tried to kiss him. Three days later, Francis Rattenbury died.

On May 27, 1935, jointly charged with murder, Alma Rattenbury and George Stoner were brought to trial at the Old Bailey, in what became one of the more sensational court cases of the period. Both pleaded not guilty. Stoner didn’t deny he had struck Rattenbury, but his counsel pleaded temporary insanity. Alma acquitted herself well on the stand; Stoner, who had more of the public’s sympathy, did not testify, and expert witness testimony to his alleged cocaine addiction proved inconclusive. On May 31, after a forty-seven minute deliberation, the jurors brought in their verdict. Alma was found innocent of the charges, but they pronounced Stoner guilty, with a recommendation for mercy. The judge had the prisoner moved to the center of the courtroom and delivered a death sentence. The execution was scheduled for June 18.

Four days later, Alma’s body, with six self-inflicted stab wounds, was found in the River Avon. Three of the wounds had penetrated her heart. Her final words were found in a letter in her handbag. “It is beautiful here,” she’d written. “What a lovely world we are in. It must be easier to be hanged than to have to do the job oneself.… Thank God for peace at last.”

Alma’s solution to her distress at Stoner’s impending execution was premature. A campaign began for his reprieve, and it was strengthened, ironically, by Alma’s suicide. Stoner’s sentence was commuted to life in prison. Seven years later he was released.

Francis and Alma are buried in unmarked graves in Bournemouth. Their son, John, followed in his father’s footsteps and became an architect with Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West Institute in Arizona. In 1998 he attended the hundredth anniversary celebration of the legislative buildings, which, together with the Empress Hotel, are the landmarks that distinguish Victoria’s inner harbour. The legislature remains Ratz’s best-known architectural achievement.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!