Love in Code

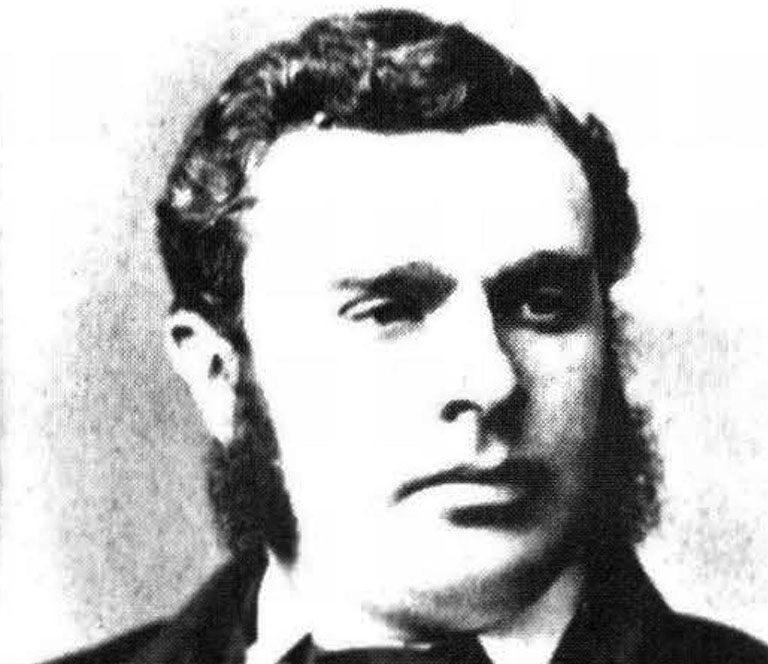

Born at Halifax in 1845, John Sparrow David Thompson served as alderman for his native city, as a member of the Nova Scotia Assembly and briefly as premier, and as a judge of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia before accepting Sir John A. Macdonald’s invitation in 1885 to serve in his Conservative cabinet.

Seven years later he was prime minister. His wife Annie and their five children did not join him in Ottawa for another three years. In the meantime, absence made the heart grow fonder.

In their correspondence, Thompson was “Grunty,” Annie was “Baby,” and their shorthand correspondence was filled with teasing entendres.

He ends several letters with a salacious promise to give Annie a good “whipping” or “warming” when he returns to Halifax. Elsewhere he writes: “I am so fond of you that I want to give you a good licking.”

Annie Affleck was a Halifax sea captain’s daughter, and it showed. Bold, vivacious, even at times reckless, she reminded one of Catherine Linton in Wuthering Heights—having measured the occasion, she was willing to throw caution to the winds.

Of a suitor prior to Thompson, she said, “Let him get now out of my mind altogether and he that I would of once dared anything for.”

That was Annie—high-spirited and unafraid. She was often a creature of her own impulses, indeed at times a victim of them, swung upon great swells of exhilaration and depression. She was twenty-three years old when she first met John Thompson, early in 1867.

Her family was a decent Roman Catholic seafaring family. She was the eldest of eight children.

Thompson came from a family perhaps less well off than hers. His father was a poet, newspaperman, teacher, friend of Joseph Howe’s, none of which could have recommended him as being well off.

John was the youngest of seven children. They were Methodists. The two families did not really approve of the courtship, though John Thompson Sr., the father, like many Methodists, believed in tolerance to Roman Catholics.

“We live and let live,” as John Wesley once put it. After Thompson’s father died in October 1867, young Thompson’s life became more complicated, for he was now the sole support of his mother and sister, his two older brothers having died abroad.

Neither mother nor sister would have welcomed the prospect of Thompson’s marrying, having children, and with a Catholic girl at that.

Annie Affleck, shown here at about the time of her marriage to Thompson in 1870, was an intelligent, sensitive, and sensual woman who kept her suitor waiting three years before consenting to be married.

She was Catholic, he was Methodist, at a time when religious differences could be an impediment to marriage.

Shorthand became their way to code their letters, but at first it provided the vehicle for their courtship. By presenting himself as Annie’s tutor in shorthand and French, Thompson was able to gain entrance to the Affleck household and disarm her parents.

Before their marriage, he also used shorthand in letters to Annie to disguise his true feelings from Annie’s mother, who he knew was censoring her mail.

Annies family’s coolness to Thompson’s courting produced a strange correspondence. Often his notes and letters were smuggled in to her. With others they devised the technique of writing their letters on the outside of a sheet of letter paper folded once.

This produced two outside pages, 1 and 4, which would be a regular hand-written letter giving news of Thompson’s doings and commending himself to her reluctant family. But on the inside pages, 2 and 3, there would be shorthand.

One such letter still exists, although once Annie had a whole box full of them. I had no idea of what those neat, clear symbols represented. I had a photocopy made and took it everywhere.

Even schools of shorthand did not know. That it was workable was certain, for both Thompson and his father both used it in reporting Nova Scotia Assembly debates.

Then in June 1978, working in the British Library in London, I brought out my dog-eared copy of Thompson’s shorthand and asked the librarian what she thought. She couldn’t solve it, but she knew someone who might, Dr. Eric Sams, who had worked on cryptography during World War II.

He cracked Thompson’s shorthand in twenty-four hours. Not only that, he ascertained its origin. It was a late eighteenth-century British shorthand, revised in Rhode Island and published there in 1823 by J. Dodge. Thompson’s father had learned it after his arrival in Halifax in 1827.

Usable it patently was, but it had some peculiarities. It did not include any vowel sounds, registering only consonants.

For example, the symbol for the letter r was a tick. That, standing by itself, could mean any one of: or, are, ire, oar, our. If one had the context, one could get the right word. But it wasn’t simple. Roar for example came out as two ticks hooked together. D was a slanted stroke, /; deed was thus, //.

That summer of 1867 Thompson began teaching Annie shorthand (and French), and by September she was keeping her diary in shorthand. It is there, in Annie Affleck’s diary, that her world of the 1860s starts to appear, and Thompson’s courtship springs into life. By July 1867 Thompson was at Annie’s five or six evenings a week.

Why they appealed to each other is a natural question, and like many natural questions not susceptible of an easy answer. Annie was bold and spirited. Thompson was quiet and controlled.

She needed, and I think liked, to have a flywheel to control her centrifugal tendencies. He enjoyed the refreshment of them. She could be cross and irritable.

“T.in.I did some French and fought” Thompson was disciplined, but he was not a cold fish. Rather he gave the impression of a powerful furnace, with coals well banked, but where an alteration of drafts and dampers could produce a raging fire.

He had a lively, if ironic, sense of humour. They talked much about work and a woman’s position — on wifely submission, as Annie put it. Submissive she was not. Nevertheless Thompson seemed to be a man Annie could lean on in the hard business of living. She had been caught by his kindness and decency.

“How could I live without him now?” she asked her diary on September 8. A few days later she confided, “I kissed Thompson tonight. Heaven help me if I am doing wrong. I can’t live without some kindness.”

Increasingly, as November came on, Annie found herself lonely when Thompson was away or could not call. Is it me, she asked herself, or merely passion, that makes me so lonesome for him? By Christmas Eve they would sit in front of the fire, his arms around her, her head on his shoulder, and she glad to feel she was not alone in the world. Upstairs later she wrote,

I am quieter and happier and thank God after all this Christmas Eve was the most peaceful and happy of all that I have spent. God guard him and I along into the dark future, be it long or short.

Her diary ends on a philosophical note on New Year’s Eve, 1867:

[Thompson is] the only one that cares for me in truth; for that I am content… if he is to be in in the evening when he kisses me and tells me that I am all to him I feel happy, and when he goes I only think that tomorrow evening I will see him again for now I live for him.… Who would have thought this night last year, that before he came to be all to me that he was to make me contented with life and that I would look up to anybody …

Annie Affleck

Halifax, December 31st, just upon the stroke of 12 o’clock, back room in Starr Street.

From this point one is admitted to their life only through Thompson’s letters to her, and hers to him. But they wrote each other nearly every day they were separated, and both were assiduous keepers of letters. Married in July 1870, between them they have probably the greatest husband-and-wife correspondence of any public figure in Canada.

Annie had nine pregnancies between 1870 and 1883. Five children lived. Thompson wrote to them, too, when he was away. He hated to be away from home. He hated to be away from his double bed with Annie. He hated electioneering, having to say things that would get attention somehow, bouncing from hotel to hotel, from one exigent constituent to another.

Annie would cheer him up with letters and firmness, holding him to his duty, and in one remarkable letter delivering stiffening and coziness at one and the same time:

I wish I could be with you for one ten minutes to talk square to you. You want to know how I’ll feel if you are beaten well child except for you being disappointed and tired to death not one row of pins. … So keep up your courage and I’ll go part of the way to meet you coming home win or lose they can’t keep you from me much longer.… So now my old baby you must not be such an awful awful baby until you get home and then I’ll see how far you can be indulged.

That was in 1882. In 1885 Annie pushed Thompson out of the house to accept Sir John A. Macdonald’s invitation to become minister of justice. Thompson did not want to go.

Annie said, “Go. Now you can show the world what you can do.”

So Thompson went. He found Ottawa very lonely without his wife and family.

Annie said to him, “Don’t mope. Go out to dinner with the men. Stop acting like a poor child out in the cold with such a ‘nobody-to-care-for-you tone.’”

When Thompson talked about giving it all up and coming home to Halifax she would write, “No, you shall not, you are there and the world must see what you are made of—so no more coaxing.”

In November 1885 when he was looking toward coming home for Christmas, Thompson made so bold as to ask her—in shorthand—if her December menstruation would be over before he came home. She answered him obliquely, November 25, “I will answer your pert question as to December in a day or two.”

Happily, the family moved to Ottawa in the summer of 1888.

Six years later, December 12, 1894, came the news of Thompson’s sudden death from heart attack in Windsor Castle. The news came at midmorning, and no one at first would believe it.

An Ottawa reporter, wretched man, phoned Annie and asked if she had news of her husband’s death. Not having even an intimation, her reaction can scarcely be imagined. Thompson had been everything to her; society, people, places, were almost matters of indifference unless it was a way to help him. It had been like that ever since 1867.

Her memory of him is enshrined in the Thompson Papers, which she assiduously collected and hovered over as long as she lived. She died of cancer in 1913, and the custodian of the papers then became her eldest son. He brought them almost untouched to the National Archives in 1949.

Happily they are there still.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!