Free the Island

Readers of the Daily Colonist who opened their papers on April 1, 1973, may have chuckled to see the front-page headline, “B.C.-ing you, Mainland.” The story described an independent Principality of Vancouver Island, its economy subsisting on legalized gambling and postage stamp sales and its citizens swearing allegiance to the Queen’s cousin, Princess Alexandra, as their sovereign. The article was so preposterous that it could only have run on April Fools Day.

Yet, less than forty years earlier, serious arguments in favour of provincehood for Vancouver Island — and perhaps even more drastic measures — had appeared in the columns of the same paper. In 1936 and 1937, in the midst of the Great Depression, a small but influential band of local politicians and businessmen looked to independence as the solution to all of Vancouver Island’s economic woes.

Under the banner of the Vancouver Island Provincial Association, they sought — and received — the support of municipal councils, chambers of commerce, and private citizens across the island. They also garnered international media attention for their quixotic campaign to “free Vancouver Island.”

The separation of Vancouver Island and British Columbia was not a new idea in the 1930s. It traced its origins back to the union of the old Crown colony of Vancouver Island with the mainland in 1866. Many people on the Island viewed that union as an unmitigated disaster. They worried that the population and economy of the mainland would overwhelm tiny Vancouver Island.

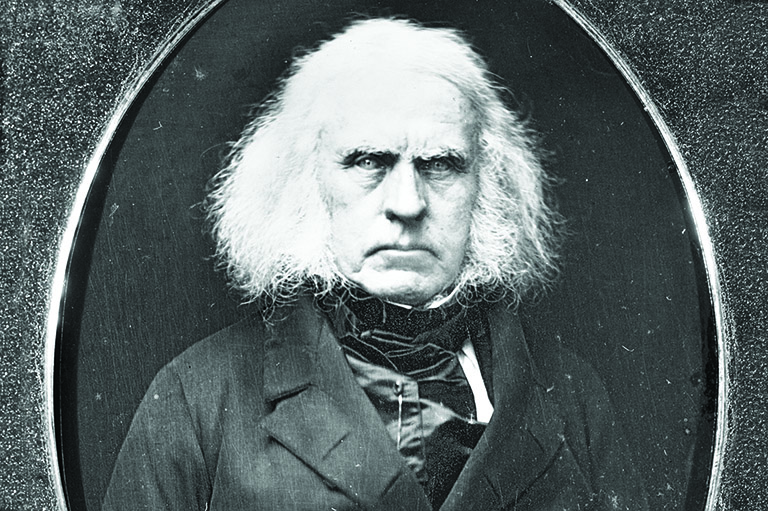

Sir James Douglas, the island’s former governor, wrote in his diary on the day of the union: “The ships of war fired a salute on the occasion — a funeral procession, with minute guns, would have been more appropriate to the sad melancholy event.”

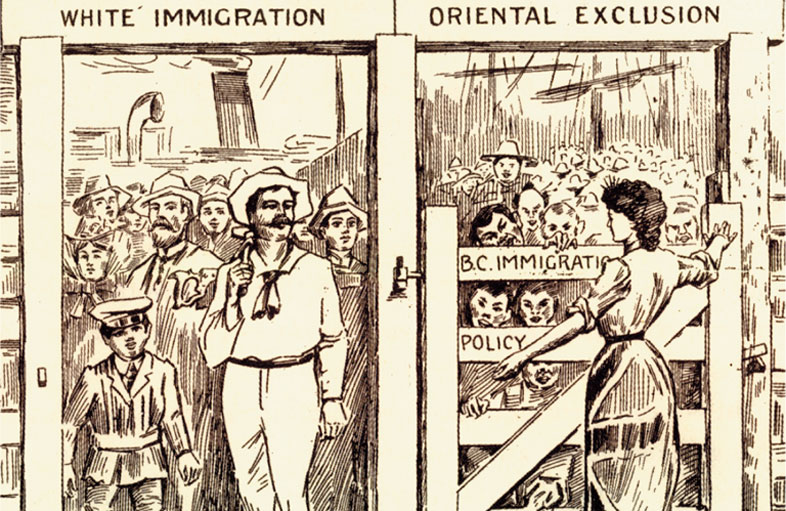

When B.C. joined Canadian Confederation to become a province in 1871, Victoria remained the capital — a source of continuing frustration to some mainlanders, who believed New Westminster or, after 1886, Vancouver should be the seat of government. In 1893, mainland businessmen plotted to declare independence from Victoria — they reportedly even created a paramilitary force to defend themselves. Another wave of separatist agitation came just after the First World War, with some unhappy islanders favouring a return to Crown colony status, or even annexation to the United States.

All of these separatist movements fizzled for lack of an influential and articulate leader. This changed in the mid-1930s, when island independence found its champion in Bruce “Pinkie” McKelvie, a muckraking journalist, popular historian, and political backroom boy.

Born on Texada Island in 1889, McKelvie rose from humble beginnings as a small-town printer’s apprentice through the ranks of British Columbia’s newspaper establishment to become president of the legislative press gallery. McKelvie’s interest in political, economic, and historical matters came together in his campaign for a “New Deal for Vancouver Island,” which he outlined in a series of articles published in the Daily Colonist in 1935.

McKelvie proposed that separate provincehood might be the solution to Vancouver Island’s economic woes. Among other things, he envisioned Victoria as a playground for the wealthy — the Monte Carlo of the Western Hemisphere — and thought the provincial legislative buildings would make a nice casino. With British Columbia hard-hit by the Great Depression, no idea seemed too far out.

Certainly the initiatives of Premier Duff Pattullo’s Liberal government did not go far enough for islanders. Pattullo put forward an ambitious program of public works projects dubbed the “Little New Deal” — patterned after American President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. But Pattullo’s deal sounded like a bad deal to islanders, who thought it favoured the mainland. McKelvie denounced Pattullo as a member of “the Brazen Amalgamated Association of Wreckers of Responsible Government” who lavished investment and political patronage on mainlanders and exhibited a “contemptuous indifference” to the plight of his island constituents.

McKelvie’s newspaper columns struck a nerve. Local politicians, business and labour groups, and appreciative readers sent a stream of letters and telegrams encouraging McKelvie to take his message beyond the editorial page. Some urged him to push for separation from Canada entirely and a return to the status of a British colony.

“We have nothing to lose and all to gain,” wrote one supporter. “The British Government would at once realize the potentialities of this beautiful Island as a playground for the globe trotters. ”Emboldened by the support he was receiving, McKelvie made his first move — mobilizing the Victoria branch of the Native Sons of British Columbia, a Masonic-style fraternal society that mixed social activities and secret rituals with historical preservation and political activism. McKelvie was a high-ranking member of the Native Sons, and his brethren were quick to call for a “better deal” at a special meeting in March 1936, and to strike a committee to research the question.

McKelvie went deep into the colonial past to explain Vancouver Island’s woes. Before the 1866 union with British Columbia, the island had prospered, in part because Victoria had been a duty free port and a centre of British Pacific trade.

McKelvie argued that uniting the two colonies was undemocratic and unconstitutional because the British government had done so over the objection of the island’s House of Assembly. As part of British Columbia, Victoria lost its free port status, and its commercial decline was assured twenty years later with the selection of Vancouver as the terminus for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

McKelvie, so fascinated with the colonial period that he named his first-born son after Sir James Douglas, longed to return his island to its pre-union glory. To prosper again, Vancouver Island needed not only investment in public works, but also the restoration of free port status for Victoria and low taxes to encourage private investment.

McKelvie went on to found the Vancouver Island Provincial Association (VIPA), which sought provincehood as its sole objective. Other leaders of the association were Francis Winslow, a trust company manager, and Harold Despard Twigg, a former MLA for Victoria and McKelvie’s longtime friend and political ally.

The association set out to transform the excitement generated by McKelvie’s provocative articles into a viable political movement. Through the summer and autumn of 1936, islanders packed community halls to hear Twigg and McKelvie itemize the island’s grievances. They distributed some four thousand copies of The Problem of Vancouver Island’s Future, a four-page leaflet explaining VIPA’s ideology and aims, and organized local branches of the movement in seventeen communities.

The separatists also founded their own newspaper. The first issue of the monthly Island Advocate appeared in November of 1936, under the peculiar patronage of British amusement park developer T.H. Eslick.

Well-known for projects in India and Australia, the peripatetic Eslick was secretary of Victoria’s Tourist Trade Development Association. Eslick saw tourism as a panacea for Vancouver Island’s economic woes. Although he did not wish to be associated publicly with the separatists, Eslick promised to bankroll the publication and distribution of the Advocate. With Eslick’s financial support behind them, the separatists hoped to distribute some 10,000 complimentary copies of the paper to the island’s voters.

The idea of turning the island into a kingdom was not new. B.C. Premier Robert Beaven suggested as much in 1882.

By the spring of 1937, however, cracks were beginning to appear in the island separatist movement. Islanders began to argue among themselves.” People who lived up-island became suspicious of the Victoria-based leadership. The Nanaimo Free Press had predicted from the very start that “the Island would take even less kindly to the domination of Victoria than they do to the domination of Vancouver.”

The association was also in dire financial straits. The response to its public fundraising appeal was disappointing. With only a few hundred members scattered across the island, maintaining momentum proved difficult and costly. Meanwhile, Eslick reneged on his promise to fund the Advocate. Although the paper was revived under new management, it only survived for two more issues. Twigg’s loans to the association accounted for most of its budget, and he was becoming increasingly frustrated with its inability to pay its bills. By July 1937, Twigg’s patience ran out; he left the association.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The separatist movement’s failure to present a clear vision for the island’s future contributed to its collapse. It was vague about its objectives. Officially separatists advocated autonomy as a separate province within a united Canada. However, it never publicly rejected the possibility of a return to Crown colony status. This left their program open to outlandish speculation.

By the winter of 1936–1937, rumours swirled that VIPA planned to proclaim a “Kingdom of Vancouver Island” and invite the Duke and Duchess of Windsor — the former King Edward VIII and his American bride, Wallis Warfield Simpson — to become their king and queen. The United Press syndicate picked up the story and it appeared in newspapers throughout North America.

Curiously, the idea of turning the island into a kingdom was not new. B.C. Premier Robert Beaven suggested as much in 1882 when the debate over where to place the terminus of the CPR reached a fever pitch. Beaven, who represented Victoria in the Legislature, asked Princess Louise, wife of the governor general, the Marquess of Lorne, if she would be interested in becoming the queen of an independent Vancouver Island.

When the notion of a separate kingdom resurfaced in 1937, the separatists increasingly became the target of ridicule. McKelvie’s case for “Home Rule for Vancouver Island,” published in Maclean’s in March of 1937, was mocked in same issue of the magazine. “In our present mood we wouldn’t worry if the quintuplets wanted to set up their own principality with Doctor Dafoe as Emperor,” wrote the editor, alluding to Ontario’s famous Dionne toddlers and their physician- guardian, Dr. Alan Roy Dafoe.

A year later, the April Fools Day issue of The Ubyssey, the student newspaper at the University of British Columbia, cast McKelvie as an aspiring dictator modeled after Adolf Hitler. The story had “Fuehrer McKelvie” occupying the Gulf Islands with a flotilla of rowboats, removing the islands’ own flag and raising in its place the flag of independent Vancouver Island. The new flag depicted Swedish-born movie actress Greta Garbo saying “Ay vant to be alone.” By this time VIPA was all but dead. If formally disbanded in late 1939.

McKelvie’s fortunes also took a turn for the worse. His job as managing editor of the Daily Colonist ended in May of 1937 — McKelvie’s inflammatory writings likely became too hot to handle for his newspapers bosses. He ran for both a provincial and a federal seat in 1937 but lost both times.

Blacklisted by the Pattullo government, McKelvie was unable to find regular employment. He distanced himself from Vancouver Island separatism and from politics generally and devoted his energy to his historical research and writing. He eventually retired to Cobble Hill on Vancouver Island, where he died in 1960. Mount McKelvie and McKelvie Creek are named in his honour.

The Depression-era separatist excitement on Vancouver Island was neither the first nor the last time in Canadian history when separation was mooted as a remedy for regional grievances. Quebec’s separatist movement is, of course, the most prominent example. Over the years, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, northern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and the British Columbia mainland have all spawned their own, usually isolated and short-lived, separatist movements.

But on Vancouver Island the idea of independence never seems to die. As recently as the summer of 2013, environmental activists Laurie Gourlay and Scott Akenhead, received national press coverage for their Vancouver Island Province movement. They hope for a referendum that would see the island declared a province by 2021, the 150th anniversary of B.C.’s entry into Confederation.

If “Pinkie” McKelvie were alive today, he would be watching with great interest.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement