Gentlemen Spies

-

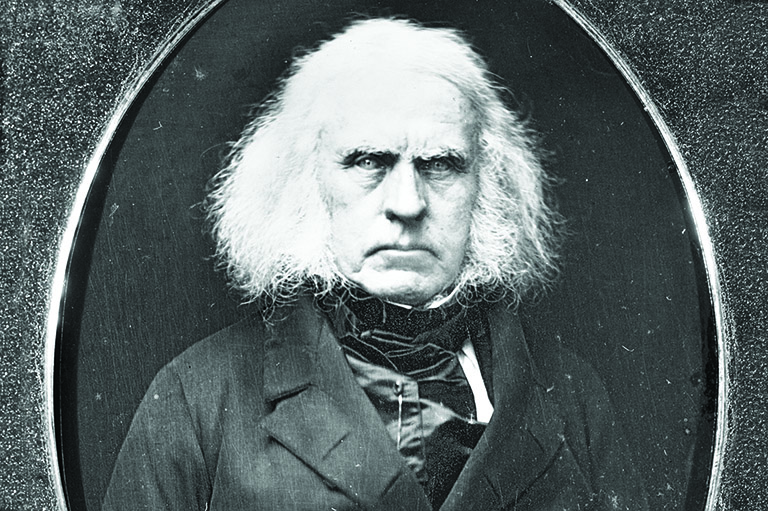

Dr. John McLoughlin, chief factor of Fort Vancouver from 1824 to 1846.Oregon Historical Society BB004249

Dr. John McLoughlin, chief factor of Fort Vancouver from 1824 to 1846.Oregon Historical Society BB004249 -

U.S. President James Knox Polk was elected on a campaign to claim all the territory on the West Coast from Alaska to Mexico.

U.S. President James Knox Polk was elected on a campaign to claim all the territory on the West Coast from Alaska to Mexico. -

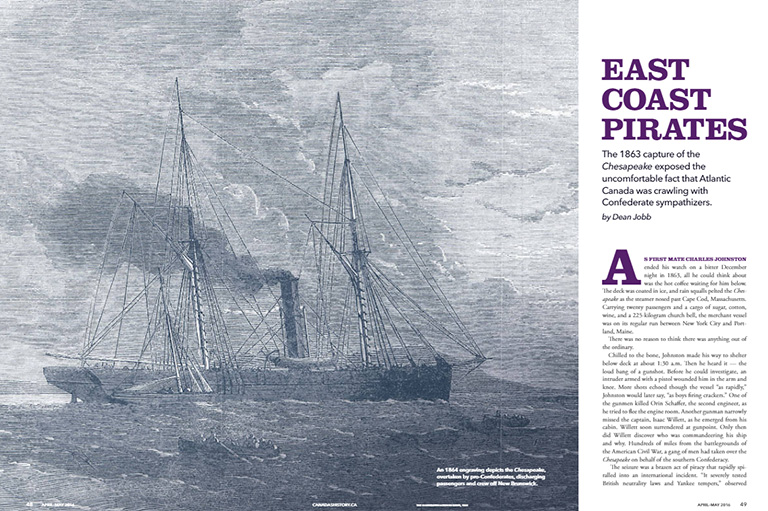

Fort Vancouver, 1845, lithograph by H.J. Warre, from Sketches in North America and the Oregon Territory (1848).Library and Archives Canada / C-040845

Fort Vancouver, 1845, lithograph by H.J. Warre, from Sketches in North America and the Oregon Territory (1848).Library and Archives Canada / C-040845 -

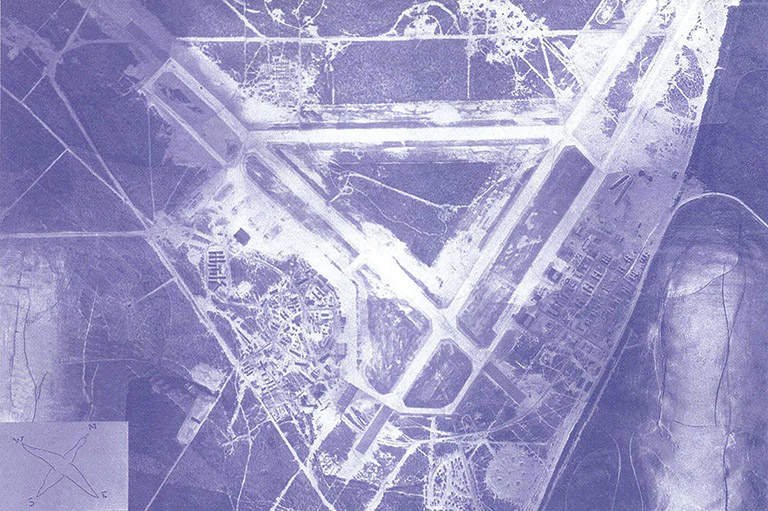

A large area of the Pacific Northwest was jointly held by Britain and the United States from 1818 to 1846. The Americans called the region Old Oregon, while the British referred to it as the Columbia District. The Oregon Boundary Treaty of 1846 fixed the international boundary at the forty-ninth parallel.Michel Rouleau

A large area of the Pacific Northwest was jointly held by Britain and the United States from 1818 to 1846. The Americans called the region Old Oregon, while the British referred to it as the Columbia District. The Oregon Boundary Treaty of 1846 fixed the international boundary at the forty-ninth parallel.Michel Rouleau

Chief factor Dr. John McLoughlin looked on in astonishment as two travelling gentlemen from England and their accompanying host of voyageurs arrived in Fort Vancouver on the morning of August 26, 1845. Even in their dusty and worn travelling clothes, it was clear they were men of standing, a cut above the usual desperate settler who came to this far-flung Hudson’s Bay Company outpost. Certainly their arrival was unexpected. Sportsmen of leisure landing at the fort from east of the Continental Divide were highly unusual, given that there was no road and little incentive to make such an arduous overland trek.

The two young travellers introduced themselves as Henry James Warre and Mervin Vavasour, British gentleman out from Montreal to enjoy the scenery and customs of the Columbia District—HBC fur-trading territory jointly controlled by the United States and Britain that included much of present-day British Columbia, as well today’s American states of Washington, Oregon, and part of Idaho.

After replacing their tattered clothing with new and expensive tweeds and beaver hats, the pair settled down for nearly a year of touring the region. An astute observer might have found their interests and choice of activities a trifle unusual.

Warre was frequently in front of his easel painting, while Vavasour had a peculiar fascination with the view from commanding hills, the location and dimensions of structures and buildings, the exact elevation of promontories, and the location of freshwater sources. Fort Vancouver, the largest settlement and the nucleus of British presence for the entire region, was of particular interest to the amiable yet eccentric pair.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

“The Fort,” wrote Warre in his journal, “is badly situated as regards defence—being commanded by a ridge of Ground running the whole length of the Plain & extending along the bank of the River.… It is surrounded by strong pickets 15ft in height 220 yds long by 100 deep at the N. West Angle is a square block house, supporting an octagonal upper story containing several small Guns.” Odd commentary for an aimless civilian pleasure seeker.

Anyone who troubled to inspect Warre’s full repertoire of sketches and paintings would have observed a pattern of peculiar themes and content. There were no portraits, few scenes of the colourful voyageurs or native peoples, no drawings of strange and exotic plants. But there was an abundance of scenery of a specific sort—outcroppings, river junctions, forts, with elevation plans and assessments of their defensibility in case of conflict—but what conflict?

Back in 1818, Britain and the United States had agreed to jointly occupy what became known as Old Oregon—all territory north of Spanish California, south of Russian Alaska, and west of the Rocky Mountains. But in reality, Old Oregon, which the British referred to as the Columbia District, remained the sole preserve of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The vast territory, populated mainly by about 80,000 native peoples from various nations, was managed by a series of rude palisade forts loosely strung together along established canoe routes and seasonal mule paths.

For the next twenty years or so, little happened to disturb the HBC’s authority in the region. It was in effect ruled by McLoughlin, the HBC’s chief factor at Fort Vancouver, who ran the Columbia District like an old-time robber baron. He was shrewd, cunning, paternalistic, and sometimes ruthless. He held court in the shadowy depths of a great timber hall behind a primitive palisade, and dispensed justice according to the dictates of his own conscience—alternately with vengeful wrath or surprising leniency as the mood was upon him.

McLoughlin opened the gates of his fort to all manner of travellers and wanderers—both aboriginal and white, British or American—so long as they didn’t undermine his authority or overtly threaten the fur trade.

The character of the region began to change in the 1840s, when an endless stream of baggy, cloth-covered wagons slowly plodded their difficult way west. The people in these wagon trains were American colonists; they were coming to settle on land that until then had been primarily hunting and trapping territory. They travelled along 6,400 kilometres of rutted tracks, trekking across barren, windblown plains, ascending alpine passes, following the shores of raging rivers through red-rock canyons, and bypassing foaming cataracts, before ending, more or less, at Fort Vancouver.

McLoughlin had a soft heart when it came to these American colonists, who were arriving at a rate of more than a thousand a year. Destitute, on the verge of starvation, and ill-prepared for the coming winter, the settlers were given credit at the company store. McLoughlin politely directed them south of the Columbia River to the Willamette Valley.

While transforming the wilderness into ranch land was not in the best interests of the fur trade, McLoughlin was not about to drive the Americans off the land or watch them starve. He also realized that a private company could not long remain the only official authority in the region; without help from the British government, holding Old Oregon would be impossible.

As settlers continued pouring in, American political interest in the region grew. In 1844, the ardently expansionist President James Knox Polk was elected on the Democratic campaign slogans “Fifty-Forty or Fight”—referring to the latitude of the northern boundary with Alaska, then held by Russia—and the “re-annexation of Texas and reoccupation of Oregon.” These threatening slogans did not bode well for British sovereignty in the territory.

Enter Warre and Vavasour.

In early 1845, General Sir Richard Downes Jackson, commander of all the British forces in North America, selected two young lieutenants for a clandestine military reconnaissance in the Oregon Territory. The first was twenty-six-year-old Warre. A well-travelled officer marked for distinction, Warre was a graduate of the prestigious Sandhurst military academy and aide-de-camp to Jackson, as well as being a talented artist. Warre’s companion, twenty-four-year-old Mervin Vavasour, was a new lieutenant with the Royal Engineers. Their orders called on them to “obtain as accurate a knowledge of (the Oregon Territory) as may be requisite for the future and efficient prosecution of Military operations in it, should such operations become necessary.”

Their mission was to scout the region, then take possession of Cape Disappointment at the mouth of the Columbia River (in present-day Washington State) and any other sites deemed useful in the event of a war. War seemed more possible as the months passed.

On May 5, 1845, the two undercover gentlemen joined a Hudson’s Bay Company fur brigade led by veteran trader Peter Skene Ogden as it forged west from Montreal. In early June they reached Fort Garry (in present-day Winnipeg) after a Herculean trek. After a short rest, they acquired horses and set off across the trackless domain of the prairies.

In their journals, the two grumbled about the quality of the food, the difficulty of the travel, the unruly behaviour of the voyageurs, and the “savage and dirty Indians.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Of their guide Ogden, Warre wrote that he was “a fat jolly good fellow, reminding me of Falstaff, both in appearance and wit.… strongly in favour of all the Indian Customs.” Although he described him as an amusing and entertaining travelling companion, Warre also declared with distate that Ogden had “a very Republican Spirit.”

The discriminating gentlemen trotted west, arriving at the snowcapped ridge of the Rocky Mountains. What most would consider awe-inspiring failed, at first, to move Warre, the condescending world traveller: “Had I not seen Switzerland, I should have been much more struck, but I had allowed my imagination too much scope [and] I was on the whole disappointed.”

Ogden led the pair through the mountains and over the Continental Divide through what Warre called “really beautiful” scenery as they occasionally hunted and fished. Eventually they reached the Columbia River near Revelstoke and floated in boats downriver to Fort Vancouver, where they were welcomed by McLoughlin, who, with his stern countenance, shock of long white hair, and six-foot-four height, presented an imposing figure.

Relieved to be in a spot of modest civilization, Warre and Vavasour bolstered their cover by making extravagant purchases at the company store, including fine beaver hats, tweed pants and coats, hairbrushes, and rose-water perfume. Now looking more like the dandies they were supposed to be, they got to work.

During the next year they huddled around smouldering fires, took shelter inside leaky log huts at HBC forts, stalked along muddy roads in the dreary mist and rain, and sweltered over mountain passes in the dust and heat of high summer.

Every place they visited they described as incapable of defence, poorly situated, or with inadequate water supplies. At Cowlitz Farms, a small settlement near Fort Nisqually (on Puget Sound in present-day Washington State), even the Catholic Church, the only defensible structure in the region, “was in want of loopholes” for guns. Warre described Oregon City as tainted by the lawlessness of the citizens, but he noted in his journal that “a small force could overawe the present American population and obtain any quality of cattle to supply the troops in other parts of the country.”

Warre and Vavasour eventually purchased land surrounding Cape Disappointment from an American settler and drew up detailed plans for its defence.

Throughout it all, the two lieutenants were impressed with the exotic world around them. They observed Mount Hood “in all its majesty & snowy Grandeur.” Warre was amazed when, from the conical top of Mount St. Helens, “suddenly a long black Column of Smoke & Ashes shot up into the Air, and hung as a Canopy over the dazzling Sky behind it… the first Volcano I have ever seen in action.”

Their reports, sent to London via Montreal, were not encouraging.

They noted that American citizens were the primary inhabitants of the region (other than the tens of thousands of First Nations peoples who were conveniently overlooked by the eastern imperial powers). The number of Canadian settlers in the territory never amounted to more than a few hundred, mostly employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Warre recognized the future in these demographics and blamed the situation on chief factor McLoughlin, saying he gave too much help to American newcomers.

“We are convinced,” Warre wrote in his report, “that without their assistance not 30 American families would now have been in the settlement.”

Angered by the report, McLoughlin wrote a lengthy reply to his superiors, stating that he had no choice but to help the desperate settlers. Otherwise they would have attacked the fort to get what they needed, which would have ruined the company’s interests in the region and possibly precipitated a war.

“As a Good and faithful Subject it was my Duty to do my Utmost to maintain peace and order Between the British Subjects and American Citizens,” McLoughlin wrote. The company did not buy his arguments and planned to transfer him to another post and cut his salary. McLoughlin resigned in disgust in 1846. He lived out his days in Oregon, where he is known to this day as the “Father of Oregon.”

Warre’s report was also critical of Sir George Simpson, governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, who believed that regular British army troops could be brought to defend the territory via the tortuous fur trade route through the mountains.

With their work done in the spring of 1846, Warre and Vavasour departed Fort Vancouver with the eastbound fur brigade. Meanwhile, the political situation in Old Oregon, unbeknownst to the inhabitants, was gathering tension. President Polk had persuaded the U.S. Congress to end the joint-occupancy accord in December of 1845. Declaring the entire region America’s, he made rumblings of war. Meanwhile, Britain sent a warship, HMS America to patrol the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

War seemed imminent. But in the end, cooler heads prevailed.

British officials knew that a war over Oregon would not be limited to the distant Pacific, but would likely be fought as an invasion of Canada. They figured it was not worth fighting for a depleted fur preserve that was already occupied by unruly American citizens.

Polk was not especially eager to antagonize Britain, either. He was already faced with an impending war with Mexico over Texas. The two sides eventually agreed that all of Vancouver Island would remain British and that everywhere else, the forty-ninth parallel would serve as the boundary. The agreement was formalized under the Oregon Boundary Treaty of June 1846.

Historians are unsure of the exact influence Warre and Vavasour’s reports and dispatches had on the border settlement—their final report was received in London too late to directly influence the border negotiations. But undoubtedly they contributed to the growing body of information that led negotiators to settle on the border as we now know it.

What their reports did was provide a graphic window, however brief and selective, into a region on the cusp of dramatic political and social change.

Manifest Destiny

The belief that the United States was divinely destined to control all of North America arose out of the Monroe Doctrine of 1823. President James Monroe told Congress that any foreign intervention in the affairs of the Americas (including South America) would be viewed as an assault on the United States.

Journalist John L. O’Sullivan expanded the concept in 1845, saying it was the nation’s “manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly Multiplying millions.” Manifest destiny became the rallying cry of American expansionists and was used to justify the expropriation of Indian lands, the war with Mexico between 1846 and 1848, and President James Knox Polk’s claim to what is now British Columbia.

Et cetera

Overland to Oregon in 1845: Impressions of a journey across North America by H.J. Warre. Public Archives of Canada, Ottawa, 1976.

Fortune’s a River: The Collision of Empires in Northwest America by Barry Gough. Harbour Publishing, Madeira Park, B.C., 2007.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement