Experiments in Peace

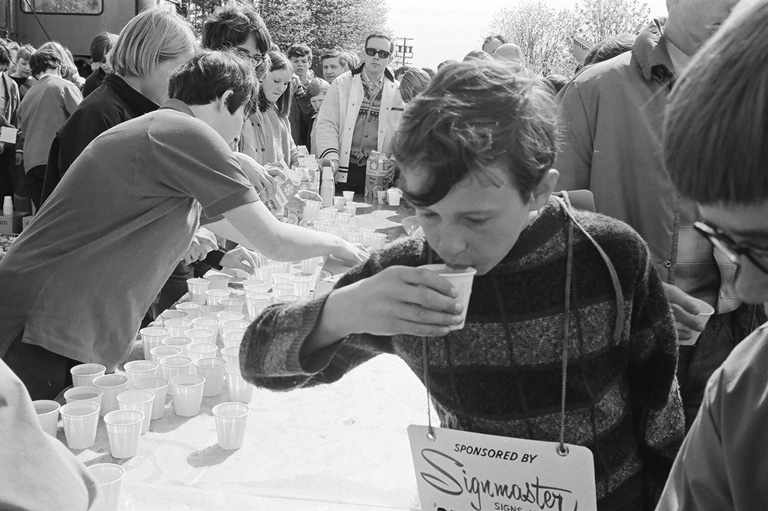

In 1965 six armed men approached the shores of Grindstone, a five-hectare private island on Big Rideau Lake, northeast of Kingston, Ontario. After landing their motorboat, they took into custody the thirty-one people who had been attending a conference on the island, including six children.

Calling themselves the Unionists, the invaders addressed their captives, explaining that they represented a right-wing movement planning to occupy Canada. No one was permitted to leave or to use the radio. Food would be withheld from anyone refusing to do what was demanded of them. Any disobedience, the Unionists insisted, would be met with violence.

Conference-goers huddled together and debated whether to submit or to resist, and where they might be able to hide the children. Someone raised the possibility of swimming for help.

A few people suggested that the peace-themed conference be continued and that the Unionists be invited to sit in on sessions. A more vocal group felt that outward displays of civil disobedience were required.

They executed a hunger strike, arranged to steal an antenna and a typewriter in order to interfere with the invaders’ ability to communicate, and protested the occupation by ringing an off-limits bell. The Unionists told the bellringers to cease or face the consequences.

After thirty-one hours of captivity, a group escalated the bell-ringing, leading to the Unionists shooting one person and gassing twelve others. As survivors processed the devastating outcome, an announcement was made: “The exercise is now closed. Umpires’ decision.”

What became known as the Grindstone Experiment was not an act of terrorism but rather role-playing designed to simulate a violent act and to test whether it could be subdued using peaceful means. The mock invasion was part of activities at the Grindstone Island Peace Education Centre, a summer program organized by the Religious Society of Friends, otherwise known as Quakers.

There was never any real possibility of harm, and no one actually died. Everyone involved was aware that the exercise was not real. The six “Unionists” were selected in advance, four of them because they had military training that organizers believed would help to create authenticity.

During the lengthy debriefing discussions and subsequent scholarly research, participants expressed disappointment that their non-violent organizing was a complete failure. The exercise, although contrived, demonstrated some of the difficulties involved in applying theory to reality.

Between 1963 and 1973, Grindstone welcomed thousands of activists, educators, students, spiritual leaders, diplomats, and journalists. They descended upon the island retreat to study the causes of war and to propose solutions that would lead to peace.

The isolated, rustic setting was seen as particularly conducive to experimental learning activities, like the mock invasion, but also excellent for encouraging meditation, camaraderie, and inspiration.

Ursula Franklin, the pacifist physicist, described Grindstone as a “mental landscape” where visitors tested their beliefs and practised strategies they would later employ off-island when confronting the threat of nuclear warfare, the tragedy of the Vietnam War, or the social unrest caused by colonialism, racial discrimination, and poverty.

Before it became a site of peace education, the island was a retreat from war, under an entirely different guise, for Charles Kingsmill, a Canadian-born captain in the British Royal Navy. After his retirement in 1908, he led the formation of the Royal Canadian Navy, in which he later served as a rear admiral.

In 1916, Kingsmill built a retreat on Grindstone Island. Located approximately eighty kilometres from Ottawa, the island was a convenient getaway: close enough for Kingsmill to return to the capital when needed, but distant enough to temporarily escape the pressures of Canada’s naval defence during the First World War.

The phenomenon of wilderness tourism, popular in Ontario early in the twentieth century, provided members of the elite like the Kingsmill family a break from the modern world. Time spent immersed in nature was thought to rejuvenate the industrialized and urbanized body.

During the Second World War, Grindstone continued to be a retreat from the harsh reality of conflict. After Kingsmill had died on the island in 1935, his widow, Lady Frances Kingsmill, opened her summer home to convalescing soldiers, sailors, and nurses.

Seven young family acquaintances, who had been evacuated from Britain during the war, joined the Kingsmill grandchildren on Grindstone Island. There they were sheltered from the physical risks of the war, as well as from many home-front hardships, since the family’s wealth and connections allowed them to circumvent most of the shortages and rationing

The surviving Kingsmill children inherited the island after their mother’s death in 1956. There was talk of selling the property, but the politically active Diana Kingsmill-Wright expressed to Globe and Mail reporter Barry Zwicker her hope that “the tranquility of their island can be extended a little into the world.”

Sent off to boarding school in England and finishing school in Switzerland, Kingsmill-Wright had returned to Ottawa to be presented as a debutante in 1929. Her early adulthood involved marriage to the son of a British lord (whom she later divorced), international travel, and competing as part of Canada’s Olympic ski team.

In 1945 she eschewed her life of privilege when she married her second husband, prairie socialist Jim Wright, and moved to rural Saskatchewan. Kingsmill-Wright became active in the cooperative, environmental, and peace movements.

As Saskatchewan’s provincial representative for the disarmament organization Voice of Women/La Voix des Femmes, Kingsmill-Wright saw ending the threat of nuclear annihilation as the most critical political cause of the 1960s.

Her son, George Gordon-Lennox, a reporter with the Ottawa Journal, was also interested in international affairs. When he heard that Grindstone might be sold, he suggested that the family retain the island but lease it to a university or not-for-profit association interested in promoting international understanding.

In 1962 Kingsmill-Wright reconnected with a Quaker friend, Murray Thomson, who worked as the peace secretary for the Canadian Friends Service Committee (CFSC), the Quakers’ peace and social-justice organization.

Since the seventeenth century, Quakers had been committed to war resistance and peace work, which, both as individuals and as communities, they furthered through conscientious objection, relief efforts, and civil disobedience. In 1947 the Religious Society of Friends was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for assisting the victims of war.

In the Cold War period, many Quakers participated in disarmament or anti-Vietnam War protests. The CFSC assisted American draft dodgers to immigrate to Canada and sent aid to civilians in North Vietnam and South Vietnam. Although “none of us knew how to run an island,” Thomson recalled, the CFSC was intrigued at the possibilities Grindstone offered in serving its mandate.

After much discussion, Kingsmill-Wright agreed to lease the island for one dollar per year to the CFSC to build a peace retreat that would operate between April and September each year.

“While the island has served as a refuge for casualties of war,” she explained in an advisory council meeting, the escalation in global weapons stocks meant “there can no longer be war but annihilation. Thus, we feel there is only one course to follow — to do what is in our power to help build the peace.”

She believed her father would have approved of the decision; in the last years of his life, she said, Sir Charles began to question the use of military solutions to resolve conflicts. He felt it was tragic that air warfare put civilians at such great risk.

With continued financial and logistical help from Kingsmill-Wright and an advisory committee drawn from representatives of different peace groups, Thomson transformed the island’s main lodge and cabins into a camp that could accommodate approximately fifty overnight guests.

Jack and Nancy Pocock, prominent Quakers and Canadian peace activists, were hired to serve as the island’s wardens, responsible for coordinating the programs and hospitality logistics.

Fourteen weekend or week-long workshops were scheduled for the first summer, on topics as varied as “Creative Alternatives to the Arms Race,” “Canadian Biculturalism,” and “Towards a Relevant Christian Peace Testimony.” Almost four hundred participants attended.

When they looked back on their experience, attendees spoke highly of the workshops but also of the relationship-building and learning that occurred through conversations while washing dishes, lounging on the porch, or canoeing.

John Schaffer, who first attended Grindstone as a university student, recalled, “It was a kind of crucible of ideas, and people, and social networks.”

Schaffer and many others noted that the residential experience was key because it helped participants to focus and to build a community. The isolation helped, too. Initially there was no phone, and the only way on and off the island was via a privately run water taxi.

By the end of the first summer, according to an internal history of the island, Jack Pocock concluded that “Grindstone has already become a concrete and visible symbol of the peace effort in Canada.”

While Grindstone’s facilitators and visitors shared a commitment to peace, they were far from a homogenous group. Participants represented multiple generations and political affiliations; at any one time the island could be home to conscientious objectors from the Second World War, Buddhists, anarchists, and university students from Africa and the Caribbean.

Unsurprisingly, Quakers made up a large portion of those involved in the workshops; but approximately one third of participants described themselves as having no religious affiliation. Among the Canadians, participants were usually white and middle-class, and the majority hailed from Ontario or Quebec. At one point, sixty-seven per cent claimed to have voted for the New Democratic Party.

Grindstone’s programming shared the same theme and goals as the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs; however, outside of its diplomat conference, its participants did not hold high-ranking positions in international affairs.

There were attempts to bring Grindstone’s ideas to the noninitiated, but for the most part the group drew women and men who were already invested in the peace movement.

Reflecting the strong connections between the Canadian and the American left, the island also attracted U.S. civil rights leaders A.J. Muste and Bayard Rustin as well as Tom Hayden, a founding member of Students for a Democratic Society.

Initially, Grindstone was just for adults, including those to whom Grindstone historian Murray MacAdam referred in Making Waves: A Grindstone Story as the “grey-haired” crowd.

While the Canadian Peace Research Institute hosted a Peace School credit course for university students, there was no programming for younger people until 1966. By then, the Quaker youth camp NeeKauNis, along Ontario’s Georgian Bay, had begun to attract a subset of youth that was immersed in the counterculture. Harried counsellors thought the solution was to send the more radical teens to Grindstone.

Thus began the High School workshop: part summer camp, part activist-in-training program. Typical camp activities such as swimming and volleyball were combined with workshops on current events.

One year the young people travelled to Ottawa to meet with the prime minister and to attend an anti-Vietnam War protest. Another year, due to brewing internal tensions, the teens analyzed their own tendencies to form cliques.

When they recalled the program, many participants considered the experience transformative. David Josephy, a biology professor at Ontario’s University of Guelph, was a high-schooler at the time of his Grindstone experience.

“Growing up in suburban Ottawa, I very much felt in the late 1960s that a revolution was going on, and I was missing it,” he said. “All these incredible things were happening, but they were happening somewhere else … and then suddenly you went into this place where you just felt like you were part of this revolution of change in the world.”

Another participant, Ted Hill, described in a letter to the Pococks a feeling of being swept away by “the overwhelming force of love and peace present at Grindstone.” The sensation faded when he returned to the United States, where he said he was just “a Black man fighting to survive again.” Later, Hill sought the Pococks’ help in immigrating to Canada to avoid registering for the draft.

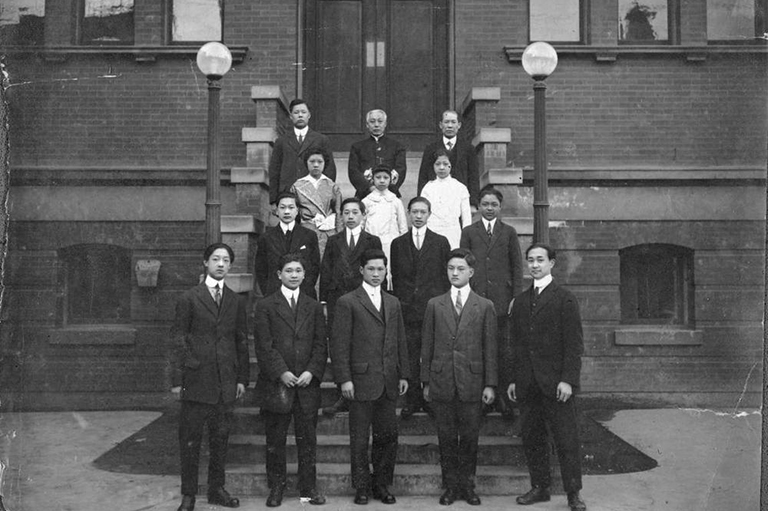

Over the years, almost one hundred diplomats from thirty-eight countries trekked to Grindstone to be part of an annual conference that attempted to forge collaboration amongst members of NATO, the Warsaw Pact, and non-aligned nations.

Sequestering delegates in a neutral place in the wilderness, organizers hoped to thaw Cold War tensions by encouraging honest dialogue about disarmament or development.

It was hoped that, outside of their embassies and away from the Ottawa cocktail circuit, diplomats might be able to make progress toward balancing national interests with international co-operation.

Program evaluations found in the Canadian Quaker Archives and Library suggest that some diplomats found the conference conducive to working co-operatively toward reconciliation and praised the Quaker efforts. Other evidence, however, suggests that Grindstone was no match for entrenched Cold War mindsets.

In August 1968, Grindstone staff learned about the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia on the radio, and this helped them to understand why all of the Eastern European participants had unexpectedly pulled out of the conference at the last minute.

American diplomats rarely agreed to participate, citing the inclusion of the Soviets as proof that the Quakers had been duped by communists. Later, the Americans refused to attend because Quakers had taken part in anti-Vietnam War demonstrations outside their embassy in Ottawa.

Sometimes the challenges of communal living offered unexpected opportunities to practise conflict resolution. While those involved in running the island’s affairs tried to operate with democratic principles and co-operative decisionmaking, tensions occasionally arose regarding rules.

Adult Quakers did not use alcohol or drugs, and they sometimes proposed banning the substances, which some adult and youth participants wanted to consume. Some recurring visitors were nudists and felt that, in the spirit of acceptance, they should be allowed to go without clothing. Eventually, one beach was put aside for skinny-dipping.

Yet for the most part there was also a great effort to model the peaceful values that people on the island were attempting to study.

One reflection from the 1965 Biases in Teaching workshop remarked that the name Grindstone was prophetic because it “conjures up images of crushing, grinding and reducing something into smaller and smaller particles. It seemed that individuals coming to the seminar full of themselves and their own personal concerns were temporarily reduced beneath the weight of the group’s concerns [and] it was clear that each participant emerged from his or her ordeal a more tender and loving person.”

For some in the local community, though, Grindstone injected an unwelcome radicalism into eastern Ontario cottage country.

“Going to Grindstone Island, you could always pick out on the ferry who were hippies and who were the cottagers, right?” Josephy quipped.

In the nearby town of Portland, persistent rumours included one that held that the island was a communist training centre and another that insisted it was a free-love colony. Occasionally, boaters would come by to buzz the island or simply to gawk in hopes of spotting something illicit.

As they did with many peace groups during the Cold War, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police kept extensive records of island activities as well as any off-island organizing involving high-profile Grindstone activists such as Thomson or the Pococks.

Grindstone staff member Larry Gordon recalled how those on the island tried to combat misconceptions by being good neighbours. They supported local businesses and once helped to put out a fire on a nearby island. Gordon hoped that friendly relations might even change some conservative community members’ negative opinions of anti-war activists.

How to respond to local hostility was the theme for the 1966 Institute in Non-Violence, the same program that organized the mock invasion.

Instead of Grindstone attendees taking on the role of the opposition, this time six members of a real Kingston motorcycle gang were invited to bully and to mildly assault the participants. As with the mock invasion, the 1966 encounters were highly charged.

Some participants broke into tears and fled to a safe house. Others focused on ignoring violence, even when personal property was vandalized or the bikers brandished knives.

In his diary, Peter Light, a twenty-three-yearold activist who had organized the 1965 protests at the Comox air base in British Columbia, described experiencing a plethora of emotions as he engaged in the role-playing: cowardice, confusion, annoyance, inspiration, and disappointment.

Over and over he allowed himself to be thrown in the lake by the gang leader, until the two of them sat together chatting on the dock. Just when Light felt a breakthrough was imminent, the biker threw him in the lake again.

During the subsequent debriefing, the gang members opened up, saying they felt the activists had talked down to them. The bikers also said they were annoyed about participants’ preoccupation with the war in Vietnam, when there was injustice and poverty in Canada. Much like the mock invasion, in which nonviolence had failed to conjure a victory, the participants deemed the exercise revelatory.

As Nancy Pocock told MacAdam, “we learned a lot about our middle-class values, about being able to understand people with different standards and a different way of looking at life.”

Others thought it was valuable to see how chaotic, emotional, and self-destructive it could be to confront violence.

Grindstone's experiments in peace and non-violence helped to prepare participants who would later engage in off-island episodes of civil disobedience, where they faced significant public and police opposition.

Those included the protests in 1964 at the La Macaza air force base in Quebec and in 1966 at Voluntown Peace Trust Farm in Connecticut, where residents faced hostility and an outright attack on their premises.

It is difficult to measure Grindstone’s legacy. Countless actions were planned and carried out. Participants formed professional and personal relationships, allowing off-island networks to develop among activists, educators, community members, and the government.

“Important things happened at Grindstone, with people from the U.S. and England as well as from Canada,” Nancy Pocock recalled in Peace Magazine in 1989. “We used to know in the summer what would happen in the peace movement the next year from what went on at Grindstone.”

Notably, the ideas to start the Student Union for Peace Action (1962–67), Project Ploughshares (1976 to today), and Peace Brigades International (1981 to today) all began at Grindstone.

Perhaps the best evidence of Grindstone’s influence, at least on a personal level, was the work of past participants and staff to form a co-operative that would keep Grindstone in existence. In the early 1970s, financial difficulties forced the Quakers to withdraw their management of the island.

Program attendance had fallen, a trend attributed to fatigue and shifting interests among activists. Furthermore, even with rent of one dollar a year, it was becoming financially onerous to maintain the aging property and infrastructure. All of these factors contributed to the CFSC declining to purchase the island when Kingsmill-Wright listed it for sale in 1973.

The Grindstone dream did not die; it evolved. Former staff and participants invested ninety-two thousand dollars to create a co-operative, which allowed them to purchase the island and to continue operations until 1990.

Under the co-operative’s leadership, peace remained central to the island retreat’s activities; however, programming expanded to support other social justice projects ranging from environmentalism to feminism.

In their 1969 program report, Janet and Philip Martin, former island wardens, concluded, “it is next to impossible to assess the value of the Grindstone experiment. How can we know what influence a few days at Grindstone have on, say, a Russian diplomat forced (or willing) to defend his country’s oppression of Czechoslovakia? Or on a girl from Lesotho, who for ten days was treated as an equal on the Island but was soon going back to a country dependent for its existence on South Africa with its degrading apartheid?”

Fifty years later, it is clearer what Grindstone represents. It is a reminder of the long history of Quaker peace work in Canada, one that goes beyond individuals’ war resistance and relief work to extensive critical thinking and action on how to build a peaceful world.

Grindstone captured the spirit of optimism within the Canadian peace movement in the 1960s and 1970s, including the belief that a non-violent solution to conflict and war could be found. For many, escaping to the wilderness to be among people dedicated to peace and social change was a transformative and inspiring experience.

Admittedly, as the disappointing outcome of the mock invasion demonstrated, others left disillusioned at the lack of viable peaceful theories or actions to overcome conflict. While Grindstone’s work did not lead to revolutionary outcomes, its legacy was the unique value it placed on community and education as the foundations of peace.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!