Standing Together

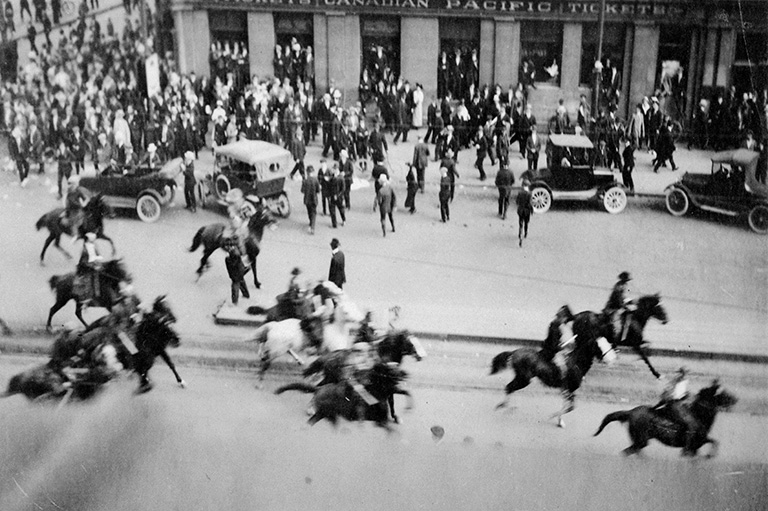

Saturday, June 21, 1919, Winnipeg’s Main Street was in chaos. The broad expanse in front of city hall echoed with horses’ hooves, the crack of batons, and gunfire as the North West Mounted Police and recently recruited “special” police attacked a peaceful crowd rallied by First World War veterans who had recently returned from the trenches of Europe. Two protesters were killed and dozens were wounded among the crowd that had assembled to voice support for striking workers in the city.

Over the six preceding weeks those workers had stood solidly against efforts to cajole or to threaten them to return to work, and on this day they were defying the mayor’s ban on parades in order to protest the early morning arrests of strike leaders a few days earlier. The terrible events of June 21 — “Bloody Saturday” — reflected both the strength and the effectiveness of the workers’ protest, as well as the fear and anger it had unleashed among the governing and business elites of both the city and the country. Much more than simply a limited action by organized labour, the Winnipeg General Strike was a revolt by tens of thousands of ordinary people. How had it come to this?

The immediate answer lay in the strike itself. The core issue seemed unexceptional: Workers in Winnipeg’s metal and building trades had gone on strike in early May of 1919 to force employers to negotiate. What followed, though, was remarkable. When the strikers appealed for support from the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council, it agreed to organize a general strike. The council sent the proposal to its affiliated unions, whose members voted yes by a margin of about eleven thousand to five hundred.

The strike was set to start at eleven o’clock on the morning of May 15, but when the day shift of telephone operators did not show up for work at seven o’clock it was clear the strike had begun. The phones fell dead. Soon factories and shops closed, streetcars disappeared from the city streets, mail went undelivered — the city ground to a halt. The ranks of the strikers swelled to more than thirty thousand, considerably more than the number of unionized workers in Winnipeg. In total, about half of the families in Winnipeg had a member on strike.

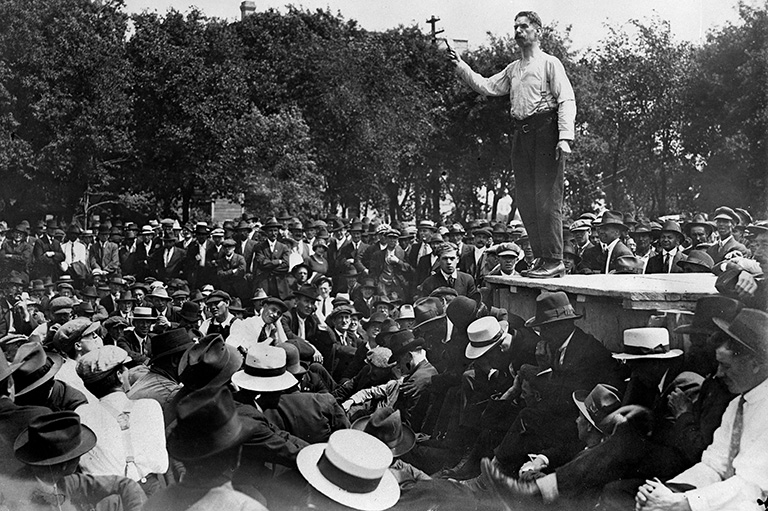

Returned soldiers were a huge and volatile force in the city and, like the city itself, were divided in their sympathies. The majority were working men, and they soundly defeated a motion from the leadership of the veterans’ organization that they remain neutral. At a mass meeting held on May 15, rank-and-file soldiers voted their full sympathy for the strike. The spark — that unexceptional demand for collective bargaining — had ignited a blaze.

In 1918, record numbers of workers in North America had gone on strike, as in a one-day walkout in Vancouver in August.

A deep undercurrent of anger had been exposed, and its sources were not hard to identify; indeed, many of them were long-standing. With the rapid settlement of the prairies around the turn of the twentieth century, Winnipeg had become a boom city, with clear winners and losers. It had more millionaires for its population than any other city in Canada, but it also had sprawling slums. Skilled craftsmen faced hard-nosed employers unwilling to cede any of their power and wealth. The North End, peopled by Ukrainians, Jews, and other immigrants, mostly from Eastern Europe, was a world separated from “British” Winnipeg by language, culture, and poverty.

Advertisement

What united workers — from the most poorly paid immigrant to highly skilled British-Canadian craftsmen — was a precarious labour market. When a deep economic depression hit in the years around the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, hardship was widespread. The war brought little relief. Eventually there were plenty of jobs, but unprecedented inflation meant it was no easier to put food on the table. At the same time, profiteers raked in fortunes supplying shoddy goods to the soldiers overseas and provided a steady stream of scandals.

A profound sense of injustice among workers, along with growing demand for their labour in the war economy, fuelled a new militancy. Workers joined unions at an unprecedented pace, and the number of strikes skyrocketed even before the war was over. These newly unionized and radicalized workers increasingly asked difficult questions.

Many of them saw the war’s appalling waste of life as an indictment of the entire social system and blamed capitalism as the source of militarism and imperialism. At a meeting in January 1919, George Armstrong, who would be elected to the provincial legislature in the wake of the strike, spoke of those connections.

“During the four years of war, the wealth of Canada had increased from eight and a half billions to nineteen and a half billions, in spite of it being the most destructive period in the world’s history. What better scheme had our ruling class for the future to increase the nation’s wealth than that just past?”

Working people in general had been called upon to make great sacrifices in the interest of the state; in return, they had been promised, in the vaguest of terms, a better future when the war was won. Although they met this promise with suspicion, they were beginning to find hope in their own efforts, as labour became a force for change around the world.

Most dramatically, workers had overthrown the tsar in Russia, declared a workers’ state, and taken the country out of the war. In Germany, sailors mutinied, and workers’ uprisings swept much of the country as armistice negotiations were underway, hastening the end of the war itself. Europe seemed to be on fire, and North America was perhaps not far behind.

In 1918, record numbers of workers in North America went on strike, as in a one-day walkout in Vancouver in August. And in February 1919 a general strike broke out in Seattle.

Winnipeg workers were feeling their own power. On four occasions in 1918 organized labour was able to use the threat of its collective weight to win concessions from employers.

At a major convention of Western Canadian labour in Calgary in March 1919, delegates discussed abandoning the old structure of craft organization; instead they proposed a “One Big Union” of all workers with the general strike as their key weapon.

Unions were growing quickly — five thousand Winnipeggers joined unions in the first nineteen days of May — and they were becoming more united. Unions representing individual crafts increasingly joined together to bargain and to strike, markedly increasing their effectiveness.

At the beginning of May, when the Winnipeg metal trades unions demanded to negotiate through a central council of all the unions in the industry, the employers dug in their heels. With hundreds of thousands of steelworkers, coal miners, and textile workers striking in the United States, employers felt they not only had to hold their ground on the issues being contested but, moreover, had to defeat what they saw as the threat of the growing power of labour.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

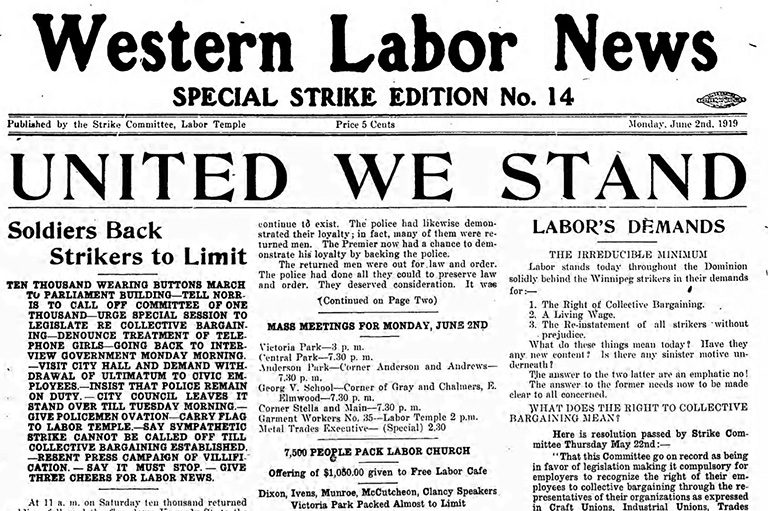

Such active solidarity, Winnipeg workers hoped, could help them to obtain two things: collective bargaining and a living wage. Members of the city’s elite painted the actions of labour very differently. The Citizen, the newspaper of the Citizens’ Committee of 1,000 — the organization of Winnipeg employers and professionals who opposed the strike — declared the workers’ actions “a Revolution … a serious attempt to overturn British institutions … and supplant them with the Russian Bolshevik system of Soviet Rule.”

Radical ideas were indeed growing amongst a segment of labour. Many participants at the Calgary convention loudly heralded events in Russia, and growing connections between union membership and political radicals were apparent in the famous Walker Theatre meeting in Winnipeg in December 1918. Co-sponsored by the Trades and Labor Council and the Socialist Party, the meeting attracted 1,700 attendees who cheered the Russian Revolution. But on both occasions the speeches focused on Canada, the federal government’s restriction of civil liberties, and the plight of workers in this country. Speakers and delegates alike were inspired by tales of the power of labour in Russia to fight oppression and to resist war.

“It is true that the capitalist class of the world has fastened upon the rising democracies chains which bid fair to stay, and unless we rise to the occasion and break them, the Labor movement throughout the world will forever be in bondage,” said Bill Hoop, a Walker Theatre speaker and long-time activist. “Today, in spite of the world-wide suffering, we have a glimpse of a world just a little beyond, which looks beautiful.”

The Citizens’ Committee attempted to underwine the strike, claiming that “enemy aliens” were importing Bolshevik ideas.

The size and character of the 1919 strike sent shock waves through Winnipeg’s elite. The labour movement — which many employers had opposed all along — had transformed from one made up mainly of what those elites considered “respectable” British-Canadian skilled workers to one that was not only becoming more powerful but was also attracting more supposedly “dangerous” workers drawn from the ranks of eastern European immigrants who were receptive to socialist ideas. These less-skilled workers had become increasingly active in labour activities during the war, with many participating in the Walker Theatre meeting and, in May 1919, joining the general strike.

This was an astounding development, given the deep ethnic divisions that ran through Winnipeg. As recently as January 1919, a large crowd made up mainly of returned soldiers had smashed store windows in the North End, broken into the homes of apparent “enemy aliens,” demanded to see naturalization papers, and made immigrants and those whom the crowd considered radicals kiss the Union Jack.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

To the surprise of those making such arguments, their appeals fell flat. Strikers were aware that the leadership of the strike included few non-British immigrants.

The returned soldiers — whom the Citizens’ Committee felt would be particularly susceptible to such a narrow patriotism — were unmoved. Although many pro-strike soldiers continued to deride “enemy aliens,” their anger against the authorities was too strong. As one veteran declared of the Mounties on Bloody Saturday, “They treated us worse than we ever treated Fritzy.”

If anything, more and more Winnipeg workers acted in keeping with the Calgary convention’s declaration that there was “No Alien but the Capitalist.”

The Committee of Fifteen, elected to lead the general strike, was aware that disorder would play into the Citizens’ Committee rhetoric and instructed strikers to “do nothing” — to avoid confrontations with authorities or with potential strike-breakers.

Strikers gathered almost daily near city hall, in Victoria Park, or in other locations around the city to hear updates on the strike, discuss events, and rally their spirits. They also urged the city’s police, who were unionized and generally sympathetic to the strike, to stay on the job and to ensure order. If labour held solid and avoided provocation, workers were sure they could win.

Adding to their confidence was the feeling that they were riding a wave. General strikes — or something close to them — broke out in as many as three dozen towns and cities from Amherst, Nova Scotia, to Victoria. While weaker labour unity in the crucial industrial city of Toronto led to the defeat of the short general strike there, in every significant city in Western Canada the strikes were, at least partly, in support of Winnipeg workers.

Saskatoon provides perhaps the best example.

The city’s daily newspapers and the mayor egged them on, and no arrests were made. The Citizens’ Committee attempted to exploit such sentiments in order to undermine the strike, claiming that “enemy aliens” were importing Bolshevik ideas and causing Winnipeg workers to abandon “British democracy.”

Although there were no outstanding local disputes in that city, Saskatoon’s Trades and Labour Council voted unanimously to endorse a general strike in sympathy with Winnipeg’s. Thirteen of the seventeen unions in the city voted to strike, staying out until Winnipeg strikers returned to work.

It was a testimony to the spirit of solidarity that workers in other cities were willing to endure weeks of deprivation and threats of dismissal in support of a cause that had been undertaken hundreds of kilometres away and whose outcome was increasingly uncertain.

Of course, workers who lived near the margin at the best of times found it difficult to struggle through a long strike; that they did so speaks to their anger and resolve. Many, no doubt, had assumed that a general strike would immediately force the hands of the employers. When it didn’t, the strike became a long, hard slog.

In an article titled “Strikers, Go Forward, Not Back,” the strike bulletin of the Western Labor News reminded those who were growing discouraged that, “To go back breaks the solidarity of the strikers and puts those who go back on the side of the bosses and so helps to defeat those who still remain on strike.” Solidarity from across the country sustained Winnipeg workers’ morale.

A Winnipeg crowd of eight thousand greeted B.C. labour leader W.A. Pritchard with thunderous applause when he told them, “If you are whipped, we are whipped. If you go down, we will go down in the same boat. But if you are to be victorious, we must help you. And we will.” Across Canada, vast numbers of workers felt they were in the fight together.

When the federal government first threatened and then fired Winnipeg postal workers for participating in the general strike, postal workers and their supporters in several cities walked off the job.

The federal government was also deeply worried that the general strike would involve not only the Winnipeg railway shop craftsmen who had already joined the general strike but also the running trades (employees who worked on the trains), a result that would shut down the national transportation system. In that case, it was easy to imagine that the strike would spread throughout the region and quite possibly the country.

After all, the issues that had provoked the general strike were hardly confined to Winnipeg.

With support for the strike extensive and growing, governments and employers knew defeating the strikers without provoking a wider conflict would be a challenge.

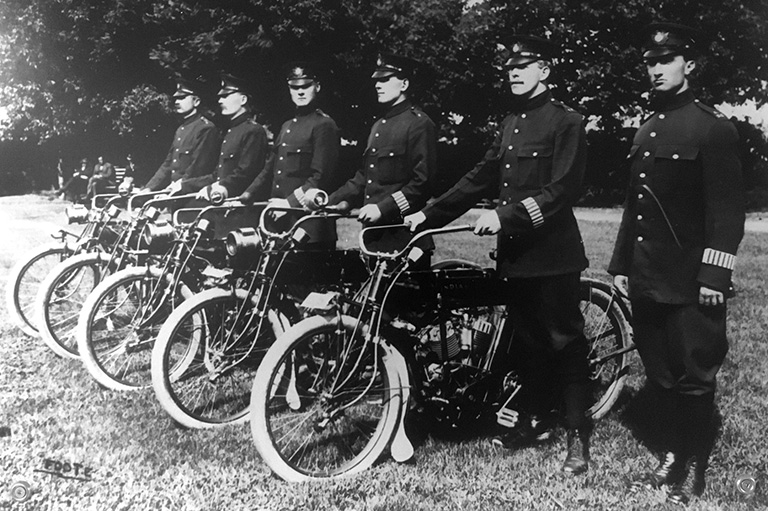

Winnipeg civic leaders and the Citizens’ Committee didn’t trust the police — the police union had recently voted to strike over wages, although a settlement had been reached. On May 29, the city demanded that each officer sign a loyalty oath, promising not to affiliate with “outside” organizations (such as the labour council) and not to join the sympathetic strike.

In spite of the police union’s assurances to city council, most officers refused to sign the oath; to the authorities, that refusal seemed to indicate that the police were unreliable.

On June 9, almost the entire force was dismissed and replaced by untrained, anti-strike “special” police, soon simply known as specials. The strikers’ newspaper labelled them thugs. The day after they were hired, the specials started throwing their weight around, attempting to disperse a crowd near the downtown intersection of Portage Avenue and Main Street and provoking a two-hour melee, which they lost.

It was clear even to the Citizens’ Committee that the workers controlled the streets of Winnipeg.

At about the same time, another danger emerged: a negotiated settlement. A mediation committee organized by the railway running trades seemed to be making headway in the metal trades dispute, perhaps leading to the recognition of the metal trades council.

The Citizens’ Committee, and particularly lawyer and former Winnipeg mayor A.J. Andrews, enlisted Gideon Robertson, the federal minister of labour and a Conservative trade unionist, to prevent a settlement in which the unions could be seen as having made gains. Andrews believed a definitive labour defeat was necessary to discredit the general strike as a tactic.

It was Andrews, acting of his own accord and disregarding his lack of legal authority, who decided the time had come.

He organized raids and arrests during the night of June 16–17, 1919, that targeted the most well-known leaders associated with Winnipeg labour and socialism. R.B. Russell, William Ivens, John Queen, A.A. Heaps, Roger Bray, and George Armstrong were arrested in Winnipeg and charged with seditious conspiracy, as were R.J. Johns in Montreal and W.A. Pritchard in Calgary.

Five “aliens” — non-British immigrants — were also picked up, in large part, it seems, to validate the idea that the strike was a conspiracy led by foreigners: Mike Verenczuk (a victim of mistaken identity), Michael Charitonoff, Moses Almazoff, Oscar Schoppelrei, and Samuel Blumenberg. These arrests led directly to the events of Bloody Saturday.

The arrests were the final attempt to nail shut the coffin of radicalism and to disperse the general strike. Andrews again took the lead in the subsequent prosecutions, overcoming the hesitations of the provincial and federal governments. He had successfully pushed Sir Robert Borden’s government in Ottawa to amend the Immigration Act to allow the deportation of British-born defendants (only Armstrong was born in Canada), but in the end he chose not to use it.

By having the public trials of 1920 prosecuted under the Criminal Code, British legal norms could be seen to be upheld and, even more importantly, a public lesson could be taught.

The defendants were not to be tried for the strike itself but for their ideas. To prove seditious conspiracy on their part, their statements, their writings, and their libraries would be trotted out. Indeed, other than Russell, the actual leaders of the strike were neither arrested nor tried; the defendants were in fact pro-strike figures best known for their political ideas.

Socialism itself was what would actually be put on trial and — Andrews and the Citizens’ Committee members hoped — would be shown to be the source of the strikers’ seditious ideas. Radicalism would be criminalized.

The defendants would be tried by a jury of rural people, who were likely unfamiliar or unsympathetic with the aims of urban labour. The jurors were chosen from a pool examined ahead of time by the North West Mounted Police and the McDonald Detective Agency to ascertain their views about the strike, socialism, and trade unions. This guaranteed convictions in most of the cases. Andrews, however, characterized the efforts as ensuring “an impartial and fair jury.”

Nevertheless, the Citizens’ Committee’s courtroom victories were less significant than they appeared.

Each of the defendants put up a spirited defence. Dixon and Pritchard, in particular, used the trials as a platform to defend their ideas. Their long addresses to the jury were published and circulated. Pritchard’s speech was rambling, erudite, and passionate.

“Work, work! Let us listen to the song, a psalm of praise, to work, as it comes tripping from the lips of a corporation lawyer,” he exhorted during his sixteen-hour address. “Did he ever work in a coal mine? Does he know what it is to bend his back before the face of the rock, or push wagons from the drive to the bottom of the shaft?”

Pritchard was convicted, as were six others. Fred Dixon was acquitted of seditious libel. He had taken over the strikers’ newspaper after it had been banned, and James S. Woodsworth had done the same. The prosecution dropped charges against Woodsworth, rather than risking another defeat.

In Winnipeg and elsewhere, labour rallied to the defence of the men who had been charged. In the next provincial and federal elections, wearing their arrests as a badge of honour, several of the defendants won election even as they sat in jail. The defence committee established to raise money for the legal expenses of the arrested men declared: “Prison Bars Cannot Confine Ideas.”

The repression of the strike and the imprisonment of some of its leaders only served to confirm the anger and frustration that had prompted it. The aftermath led many workers into the One Big Union that, led by Russell, took form in the months after the strike. The strike had also provided an intense political education for Winnipeg workers.

Several strike leaders put their experience to use by helping to form the Independent Labour Party and, eventually, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, which sent Woodsworth and Heaps to the House of Commons and a regular stream of candidates to the provincial legislature and city council. Queen would become mayor of Winnipeg in the late 1930s.

The strike also helped to give impetus to the Communist Party, which, over the next six decades, had some electoral success as well — particularly at the municipal level in Winnipeg.

After the strike, the electoral map of Winnipeg was clearly marked by divisions between working-class neighbourhoods, where labour and socialist candidates often won, and middle-and upper-class neighbourhoods, which voted solidly Conservative. Labour militancy and determination became, for some, a characteristic of the city.

In 1935, for instance, when men took to the rails in the On-to-Ottawa Trek protesting conditions in Depression-era unemployment camps, Prime Minister R.B. Bennett chose to break up the trek in Regina, rather than allowing it to proceed to Winnipeg, where thousands more were expected to join the protest.

Almost fifty years to the day after Bloody Saturday, Manitobans from the province’s most ethnically diverse, working-class constituencies finally elected a New Democratic Party government whose roots were directly planted in the general strike. And that wouldn’t be the last time that political and social conflicts in Manitoba elicited references to the great battle, which is now a hundred years in the past.

Timeline of turmoil

April 24, 1919

Metal and building trades unions present requests for wage increases and a forty-four-hour work week to the Winnipeg Builders’ Exchange.

May 1, 1919

Unions represented by the Building Trades Council go on strike after three fruitless months of negotiations.

May 2, 1919

The Metal Trades Council calls for a strike of its members at three large workplaces.

May 11, 1919

Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council (WTLC) members start voting on whether to walk out in sympathy.

May 13, 1919

Before all ballots are cast, the WTLC announces that there is a majority in favour of a general strike.

May 15, 1919

The general strike begins. Thousands of unorganized workers join those who are unionized.

May 16, 1919

The Citizens’ Committee of 1,000 forms to oppose the strike.

May 22, 1919

Arthur Meighen, acting federal minister of justice, and Senator Gideon Robertson, federal minister of labour, arrive in Winnipeg.

May 25, 1919

Robertson threatens postal workers with firing unless they return to work. Five thousand strikers meet in Victoria Park to reject this ultimatum and others.

May 29, 1919

The city police chief notifies officers that they have until 1pm the next afternoon to sign a pledge not to participate in the strike. They refuse but vow to uphold the law.

June 1, 1919

Ten thousand First World War veterans march to the Manitoba legislature.

June 9, 1919

Virtually all Winnipeg police officers are fired. The Citizens’ Committee begins recruiting replacements, known as “specials,” to enforce order.

June 16–17, 1919

Mounted police arrest ten purported strike leaders and take them to Stony Mountain penitentiary north of the city, resulting in a flood of protest across Canada.

June 21, 1919

The specials and mounted police attack participants in a silent parade called to protest the arrests. “Bloody Saturday” ends in one death and scores of injuries. A second man dies later.

June 26, 1919

At 11am in the morning, the Winnipeg General Strike ends. Hundreds of people involved in the strike will be arrested over the coming days.

In today’s environment of misinformation and disinformation, it can be hard to know who to believe. At Canada’s History, we tell the true stories of Canada’s diverse past, sharing voices that may have been excluded previously. We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past, highlighting our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages – award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts. Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.